Translate this page into:

Nail tic disorders: Manifestations, pathogenesis and management

Correspondence Address:

Archana Singal

Department of Dermatology, University College of Medical Sciences, New Delhi - 110 095

India

| How to cite this article: Singal A, Daulatabad D. Nail tic disorders: Manifestations, pathogenesis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:19-26 |

Abstract

Nail tic disorders are classic examples of overlap between the domains of dermatology and psychiatry. They are examples of body-focused repetitive behaviors in which there is an irresistible urge or impulse to perform a certain behavior. The behavior is reinforced as it results in some degree of relief and pleasure. Nail tic disorders are common, yet poorly studied and understood. The literature on nail tic disorders is relatively scarce. Common nail tics include nail biting or onychophagia, onychotillomania and the habit tic deformity. Some uncommon and rare nail tic disorders are onychoteiromania, onychotemnomania, onychodaknomania and bidet nails. Onychophagia is chronic nail biting behavior which usually starts during childhood. It is often regarded as a tension reducing measure. Onychotillomania is recurrent picking and manicuring of the fingernails and/or toenails. In severe cases, it may lead to onychoatrophy due to irreversible scarring of the nail matrix. Very often, they occur in psychologically normal children but may sometimes be associated with anxiety. In severe cases, onychotillomania may be an expression of obsessive-compulsive disorders. Management of nail tic disorders is challenging. Frequent applications of distasteful topical preparations on the nail and periungual skin can discourage patients from biting and chewing their fingernails. Habit-tic deformity can be helped by bandaging the digit daily with permeable adhesive tape. Fluoxetine in high doses can be helpful in interrupting these compulsive disorders in adults. For a complete diagnosis and accurate management, it is imperative to assess the patient's mental health and simultaneously treat the underlying psychiatric comorbidity, if any.Introduction

The literal meaning of “tic” is a persistent, recurrent or repetitive behavioral trait that is difficult, if not impossible to control voluntarily. When tics involve the nail unit, these are termed “nail tic” disorders. These disorders straddle the realms of both dermatology and psychiatry. A dermatologist should have a comprehensive understanding of these, for which a familiarity with psychiatric terminology is required.

In the field of psychiatry, various mental disorders are classified according to two established systems of classification: Chapter V of the International Classification of Diseases-11 produced by the World Health Organization and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders produced by the American Psychiatric Association. For ease of communication, broadly both these systems tend to converge, but differences do exist.

“Body-focused repetitive behavior” disorder is characterized by difficulty or inability to resist the urge or impulse to perform certain behaviors that cause a degree of relief. The behavior is perceived as a pleasant state; thus, it is negatively reinforced and tends to persist.[1] In the long run, such behavior may lead to harmful physical and psychological problems.[2] Often these behaviors are simply referred to as nervous habits.[3] Conditions such as skin picking (dermatillomania), hair pulling (trichotillomania) and pathologic nail biting (onychophagia) are classically included in this subset. In both the classification systems, repetitive behaviors, including trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder have been listed under the spectrum of obsessive-compulsive disorders.

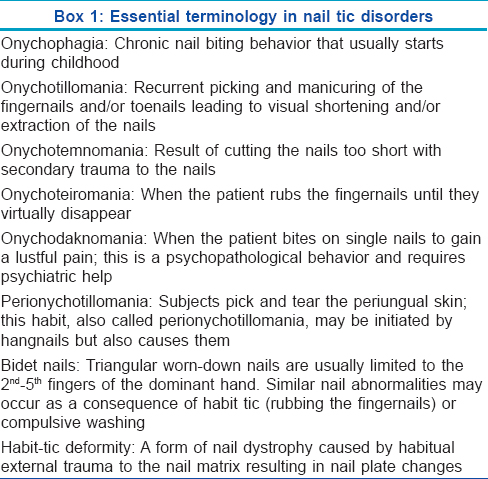

Nail tic disorders [Box 1], though common, are some of the most poorly understood, researched and misdiagnosed disorders.

Onychophagia

Onychophagia or nail biting is defined as “putting one or more fingers in the mouth and biting on the nail with teeth.”[4] The behavior pattern usually starts in childhood or adolescence and may persist in adulthood. The condition is usually limited to the fingernails and there is no predilection to bite any one nail.[5]

Epidemiology

Epidemiological data on onychophagia are limited with no large scale prevalence studies. This may be because onychophagia is often not considered a disorder at all and medical attention is generally not sought. It is often picked up by the physician accidentally, when patients present with some other disorder.

Onychophagia usually develops in childhood, after the age of 3 to 4 years.[6] In America, the prevalence of onychophagia in preschool children was reported to be 23 per cent.[7] It increases to reach a peak in adolescence and decreases thereafter as many individuals discontinue the habit. This is supported by a study which reports a prevalence of 20–33% in 7 to 10-year-old children, increasing to 45% in adolescence,[8] but with only 21.5% of men having onychophagia.[9] In India, a lower prevalence (12.7%) has been reported, with girls being more affected than boys.[10] In an Iranian study on a community sample of schoolgoing children, the rate of onychophagia in boys and girls was 20.1% and 24.4%, respectively, with 36.8% (3–44.2) of these children having a positive family history of nail biting in at least one member.[11]

Etiology

The precise etiology is not known. It is debatable whether onychophagia is just a habit or has some underlying psychodynamics. This ambiguity is reflected in the difference in its placement in the International Classification of Diseases-11 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-V.

Onychophagia is grouped under body-focused repetitive behaviors, subgroup of obsessive-compulsive-related disorder. Obsessive-compulsive-related disorder tends to overlap with obsessive-compulsive disorders in terms of clinical features, co-morbidities and response to psycho-pharmacological and behavioral therapy.[12] Probably, the act of nail biting in onychophagia is a kind of compulsion that is associated with a sense of relief after the act. This leads to a positive feedback mechanism that maintains the habit. Onychophagia is also considered as an anxiety-related disorder.[13]

In a study, young adults often engaged in nail-biting as a result of boredom or while working on difficult problems and this may reflect a particular emotional state. On the contrary, when the individuals were involved in social interaction or reprimanded for nail-biting, the behavior was less likely to be seen.[14]

Another hypothesis is that the act of nail biting acts as a mechanism to relieve stress/anxiety which is suggestive of a negative reinforcement paradigm as the individual has learned a behavior to overcome another aversive state. Hence, it acts as a drive reduction mechanism.[15]

As is well-known, stress at different stages of the psychological development of a child is associated with different psychiatric disorders. Both thumb sucking and nail biting are considered to be due to difficulty in the evolution of the oral stage of a child's psychological development.[16] While thumb sucking is initiated in infancy, nail biting manifests after 3 to 4 years of age. Some consider nail biting behavior in early childhood as a replacement for thumb sucking.[17]

Genetic factors

Higher concordance rates among monozygotic twins as compared with dizygotic twins (66% vs. 34%) suggests a genetic basis.[17] A higher incidence of onychophagia was documented in children of parents with a history of onychophagia than without (60% vs. 15.5%).[17]

Clinical presentation

Clinically, patients present with short and damaged nails usually accompanied with hang nails or nail fold damage. Fingernails are most often affected and the involvement is more often symmetric [Figure - 1] and [Figure - 2]. In severe cases, the complete nail may be lost. Patients may develop episodes of acute paronychia due to secondary infection of the traumatized nail folds. Eventually, chronic paronychia may set in. Usually, the nails are chewed and thrown out and not swallowed; ultimately, there is an irreversible shortening of the nails.[18]

|

| Figure 1: Shortening of nail plates of both hands in a young man with onychophagia. Note the surrounding erythema and hang nails |

|

| Figure 2: Onychophagia persisting since early childhood in a 48-year-old woman |

Often, there are periods of remission and exacerbation which may mirror an apparent psychological stress. During remission, normal nail growth is resumed. During exacerbations, treatment of the underlying co-morbidity is helpful.

Hemionychophagia is a relatively new terminology which was coined with respect to a 34-year-old woman who suffered a left middle cerebral artery stroke. Six months later, the patient developed asymmetric nail biting of fingernails of the left hand which was attributed to right-sided personal neglect, probably due to a functional disconnection between thalamus and cortex.[19]

Co-morbidities

Nail biters tend to have a greater frequency of obsessive-compulsive behavior.[14] In a study of 509 individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder, 56 were found to be nail biters, a much higher prevalence than expected in the normal population.[20]

Other co-morbid psychiatric disorders include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (74.6%), oppositional defiant disorder (36%) and separation anxiety disorder (20.6%). Enuresis, obsessive compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, mental retardation and pervasive developmental disorder have also been reported.[21]

Complications

Physical complications

Acute paronychia is the most common complication, eventually leading to chronic paronychia. Skin surrounding the nails may show erythema, inflammation, excoriations, hang nails [Figure - 3], scarring or even keloid formation in severe cases. Osteomyelitis of the underlying bone and intraosseous epidermoid cyst are rare complications.[22],[23] The force of biting nails can be transferred to the root of teeth and lead to apical root resorption,[24] alveolar destruction,[6] malocclusion,[25] temporomandibular disorders [26] and gum injuries.[27] Oral carriage of Enterobacteriaceae (Escherichia coli and Enterobacter) was found to be significantly higher in children with onychophagia.[28] Onychophagia-induced longitudinal melanonychia has also been described.[29]

|

| Figure 3: Low grade inflammation, pigmentation and hangnails secondary to onychophagia |

Social complications

Socially, onychophagia is considered as immature behavior that is often reprimanded by parents or relatives. Children who bite their nails are often bullied by their friends. Nail biters are often perceived as nervous, inattentive persons lacking in social skills.[30]

Onychotillomania

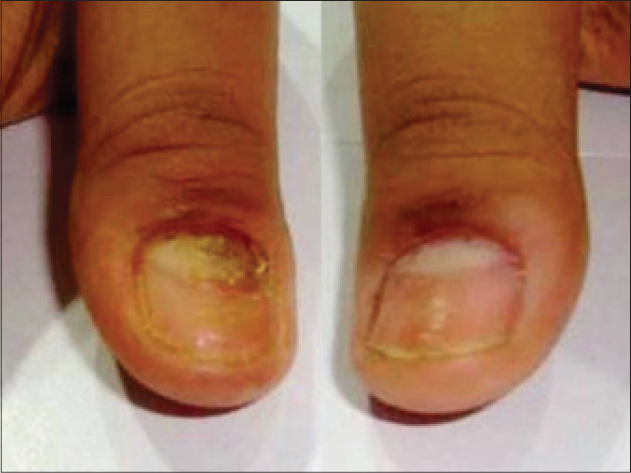

Onychotillomania, described by Alkiewicz in 1937, is an autoaggressive disorder that results from recurrent picking and manicuring of the nails.[31] It leads to visual shortening, distortion and, in severe cases, complete extraction of the nails.[32] Patients usually use their hands/nails to pick the affected nail, although anything accessible from scissors to knives to toothpicks may be used.[33]

Onychotillomania is 50 times less common than onychophagia. In a study conducted on 339 medical students in Poland, only 3 had onychotillomania.[32] International Classification of Diseases-10 classifies onychotillomania along with the other impulse control disorders such as trichotillomania.

As compared to onychophagia, onychotillomania has a higher propensity to be associated with underlying neuropsychiatric co-morbidities such as fixed hypochondriacal delusions, depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.[33],[34],[35],[36],[37] Hence, a thorough psychiatric evaluation is imperative and may help in management of the patient as onychotillomania often regresses with correction of the underlying psychiatric disorder.

Habit Tic Deformity

Habit-tic deformity is a form of nail dystrophy that results from habitual external trauma to the nail matrix that manifests as nail plate changes.[38] This is usually seen in adults and results from the habit of picking or pushing the cuticle backward [Figure - 4].[39] The patient is often unaware or unconscious of this behavior. Although any nail may be affected, involvement of both the thumbnails is classical. The offending nail is either the contralateral thumbnail or any finger nail. With single nail involvement, usually the middle finger is implicated.[40] The cuticle is often detached, damaged and may be totally missing with loss of the adhesion of the proximal nail fold to the nail [Figure - 5] thereby exposing the distal matrix leading to so-called pyramidal lunula [Figure - 6]. Constant trauma to the distal matrix manifests as loss of nail sheen. Typically, patients present with a central linear depression surrounded by parallel transverse ridges running from the proximal to the distal end [Figure - 7]. Overall, the nail resembles a washboard and hence the name “washboard nails.” In severe cases, lunulae may become hypertrophic and the proximal matrix may lie exposed.[40] A case of habit-tic deformity secondary to guitar playing that persisted for over 10 years has been reported. Stoppage of this activity led to spontaneous clearing of the proximal nail.[41]

|

| Figure 4: The act of pushing the cuticle of thumbnail with the ipsilateral index finger |

|

| Figure 5: Detached, damaged and missing cuticle on thumb, index and middle finger in a young boy |

|

| Figure 6: Pyramidal lunula on both thumbnails exposed by the pushed cuticle. Note the lost cuticle in both nails, inflamed in the right hand and accompanied by early transverse ridging of habit tic deformity in the left nail plate |

|

| Figure 7: Classical “washboard” nail of habit tic deformity with parallel transverse ridging |

This disorder is more of a habit and there is often no anxiety before the fingernail manipulation or any feeling of relief after the act. It is less often associated with psychiatric co-morbidities such as obsessive compulsive disorder.

Treatment aims at complete cessation of the habit following which the nail changes revert completely. Gentle massaging with bland ointment from the proximal to the distal end, thrice daily, was found to be effective in two-thirds of patients.[40] Use of physical barriers such as bandaging or tape application on the proximal nail fold helps both by directly preventing trauma and by acting as a reminder and deterrent to the habit of picking. Recently, the use of cyanoacrylate adhesive (a kind of instant glue) has been found to be a useful and inexpensive therapeutic modality. The glue is used to recreate the barrier between the proximal nail fold and nail plate thereby preventing further trauma and allowing time for the nail matrix to heal.[39] One should be cautious about the development of contact sensitization to the glue.

In persistent cases or in those with coexisting psychiatric disorders, a trial of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be attempted.[42] Habit reversal therapy is another alternative.[43]

This condition must be differentiated from median canalicular dystrophy of Heller (dystrophia unguium mediana canaliformis) that has a similar clinical presentation with central longitudinal splitting of the nails with multiple oblique ridges running outwardly and proximally giving a fir-tree appearance.[39] However, this entity is relatively rare and devoid of damage to the cuticle. Its precise etiopathogenesis is not known.[40]

Other Nail Tic Disorders

Published reports about the following nail tic disorders is scanty.

Onychotemnomania

Patients have a tendency to cut the nails extremely short, with scissors, blade or knife, sometimes going as far as up to the proximal end of the nails.[40] This leads to extremely small nail plates with exposed distal nail beds. It is considered a severe variant of factitious nail disorder.

Onychoteiromania

Onychoteiromania refers to extremely thin nails that crack or split easily with excessive filing or rubbing of the nail surface.[44] Patients may even file the nail folds and in worse cases, the nail bed epithelium may be reached.[40] Onychoteiromania has been considered analogous to trichoteiromania (compulsive rubbing of hair).[45]

Onychodaknomania

It is an extremely rare and almost frankly psychotic behavior where the patient bites the fingernails between his teeth (between the premolars or the canines) and is extremely painful.[44] The condition is strongly associated with an underlying psychiatric disorder. This maneuver leads to the development of irregular and deep depressions on the nail plate surface along with punctate or striate leukonychia. It is a self-mutilating behavior which is often denied and warrants a thorough psychiatric evaluation. It may respond well to combination therapy with anti-psychotics and antidepressants.[46]

Bidet nails or worn down nail syndrome

Bidet nails were first reported by Baran and Moulin in three unrelated French women who presented with a remarkably similar clinical presentation of a triangular defect in the nail plate with its base at the thinnest free edge of the nail. All three had a common obsession about their personal vaginal hygiene. The nail defect was acquired from trauma inflicted by cleaning against the glazed earthenware of the bidet.[47] Subsequently, many cases have been described with one of them developing secondary to a habit tic in an 8-year-old girl.[48] Classically, bidet nail involves the 2nd, 3rd and 4th fingernails of the dominant hand. Dermoscopy of the affected nails demonstrates dilated capillaries and pinpoint hemorrhages.[48] All these changes revert on complete cessation of the habit. Bidet nails may also be considered as a variant of onychoteiromania.[44]

Perionychotillomania

It is the habit of picking and tearing the periungual skin, also known as perionychophagia. The presence of hangnails may be the initiating factor. However, this habit itself leads to the development of hangnails, creating a vicious cycle of picking and tearing the periungual skin [Figure - 3].

Onycholysis semilunaris

This is a very common but often underrecognized factitious nail disorder that primarily afflicts women. Clinically, it presents with a sharp, distal, asymmetric onycholysis without any evidence of inflammation [Figure - 8], particularly without the proximal brownish-red margin characteristic of psoriasis [Figure - 9]. Classically, a semi-lunar shape is described in one or many nails, both in the dominant and non-dominant hand, that results from vigorous manicure with hard brushes, or use of chemicals to clean the distal nail fold. This leads to injury to the hyponychium and tends to push the distal nail fold backward. Fingernails are more often affected and many times, secondary bacterial colonization occurs, especially by Pseudomonas, at times forming biofilms. The hyponychium acts as an empty recess under the nail plate and keeps on accumulating dirt, thereby reinforcing the habit of cleaning this recess and thereby aggravating the onycholysis. Treatment is difficult as patients usually deny the habit of vigorous cleaning. The biofilms interfere with attachment of the nail plate to the separated nail bed. Thus, nails have to be cut short to the point of attachment and the free finger tips must be kept microbe-free by twice daily application of antibiotic creams. Monthly evaluation and trimming of nails may be necessary for a long period before complete resolution.[40]

|

| Figure 8: Classical onycholysis semilunaris with a white onycholytic nail plate and a regular margin in a 32-year-old woman |

|

| Figure 9: Psoriatic onycholysis in a 40-year-old woman with a classical reddish-brown band of discoloration just proximal to the irregular onycholytic margin |

Lacquer nail

Lacquer nail has significant overlap with worn down nail syndrome. It occurs as a result of excessive rubbing of the nail plate with nail filers provided with topical antifungal nail lacquers.[49]

Management

A thorough evaluation of psychiatric co-morbidities is a prerequisite before choosing the most appropriate therapeutic modality. Different treatment modalities have been tried for nail tic disorders but there is a scarcity of systematic studies evaluating the efficacy and level of evidence. N-acetylcysteine has been tried with limited efficacy in onychophagia.[50] Clomipramine was found to be more efficacious in onychophagia than desipramine in a double-blind study.[51] In onychophagia, there is preliminary Level 2 support for the first-line use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and strong Level 2 evidence for the first-line use of behavioral therapy.[52] Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are effective in severe onychophagia and onychotillomania, there are reports of treatment-emergent mania in patients with co-morbid bipolar disorder. Lithium was reported to be effective in severe onychophagia associated with bipolar disorder.[53] In patients with coexistent depression, treatment with bupropion, a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor, was found to improve the depression, associated sexual dysfunction and onychophagia.[54] Hence, it is essential to evaluate a patient comprehensively and to individualize treatment depending upon the severity of the tic disorder and the underlying co-morbid psychiatric condition, if any.

In addition to psycho-pharmacological treatment, various non-pharmacological modalities have been tried such as psychotherapy, hypnosis, cue-controlled relaxation and various behavioral treatments. There is strong Level 2 evidence for the first-line use of behavioral therapy.[52]

In behavioral therapy, various techniques can be used such as non-removable reminders for onychophagia,[55] progressive muscle relaxation, self-help techniques,[56] habit reversal,[57] aversion therapy, competing response therapies to improve nail length [58] and positive reinforcement.

Conclusions

Nail tic disorders are common yet poorly explored and grossly under-reported. There is a scarcity of data pertaining to their prevalence and there are no standard treatment guidelines. As nail tic disorders involve cosmetic concerns also, it is imperative for dermatologists to have adequate knowledge of their clinical presentation and associated psychological co-morbidities.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Siddiqui EU, Naeem SS, Naqvi H, Ahmed B. Prevalence of body-focused repetitive behaviors in three large medical colleges of Karachi: A cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:614.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Woods DW, Friman PC, Teng E. Physical and social functioning in persons with repetitive behavior disorders. In: Woods DW, Miltenberger RG, Norwell MA, editors. Tic Disorders, Trichotillomania, and Other Repetitive Behavior Disorders: Behavioral Approaches to Analysis and Treatment. Norwell (MA): Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. p. 33-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Hansen DJ, Tishelman AC, Hawkins RP, Doepke KJ. Habits with potential as disorders. Prevalence, severity, and other characteristics among college students. Behav Modif 1990;14:66-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Teng EJ, Woods DW, Twohig MP, Marcks BA. Body-focused repetitive behavior problems. Prevalence in a nonreferred population and differences in perceived somatic activity. Behav Modif 2002;26:340-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Ghanizadeh A. Nail biting; etiology, consequences and management. Iran J Med Sci 2011;36:73-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Tanaka OM, Vitral RW, Tanaka GY, Guerrero AP, Camargo ES. Nailbiting, or onychophagia: A special habit. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008;134:305-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Foster LG. Nervous habits and stereotyped behaviors in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37:711-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Leung AK, Robson WL. Nailbiting. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990;29:690-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Pennington LA. The incidence of nail biting among adults. Am J Psychiatry 1945;102:241-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Shetty SR, Munshi AK. Oral habits in children – A prevalence study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 1998;16:61-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Ghanizadeh A, Shekoohi H. Prevalence of nail biting and its association with mental health in a community sample of children. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:116.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Pacan P, Grzesiak M, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Onychophagia as a spectrum of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Derm Venereol 2009;89:278-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Sachan A, Chaturvedi TP. Onychophagia (nail biting), anxiety, and malocclusion. Indian J Dent Res 2012;23:680-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Williams TI, Rose R, Chisholm S. What is the function of nail biting: An analog assessment study. Behav Res Ther 2007;45:989-95.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Wells JH, Haines J, Williams CL. Severe morbid onychophagia: The classification as self-mutilation and a proposed model of maintenance. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1998;32:534-45.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Pearson GH. The psychology of finger-sucking, tongue-sucking, and other oral habits. Am J Orthod 1948;34:589-98.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Bakwin H. Nail-biting in twins. Dev Med Child Neurol 1971;13:304-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Lee DY. Chronic nail biting and irreversible shortening of the fingernails. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:185.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Egido JA, García AM. The forgotten nails: Hemionychophagia. Neurology 2011;77:1015.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Pinto A, Murphy DL, Piacentini J, Rauch SL, et al. Sex-specific clinical correlates of hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther 2008;46:1040-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Ghanizadeh A. Association of nail biting and psychiatric disorders in children and their parents in a psychiatrically referred sample of children. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2008;2:13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Waldman BA, Frieden IJ. Osteomyelitis caused by nail biting. Pediatr Dermatol 1990;7:189-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Van Tongel A, De Paepe P, Berghs B. Epidermoid cyst of the phalanx of the finger caused by nail biting. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2012;46:450-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Odenrick L, Brattström V. The effect of nailbiting on root resorption during orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod 1983;5:185-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Oliveira AC, Paiva SM, Campos MR, Czeresnia D. Factors associated with malocclusions in children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008;133:489.e1-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Winocur E, Littner D, Adams I, Gavish A. Oral habits and their association with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in adolescents: A gender comparison. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006;102:482-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Krejci CB. Self-inflicted gingival injury due to habitual fingernail biting. J Periodontol 2000;71:1029-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Reddy S, Sanjai K, Kumaraswamy J, Papaiah L, Jeevan M. Oral carriage of Enterobacteriaceae among school children with chronic nail-biting habit. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2013;17:163-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Anolik RB, Shah K, Rubin AI. Onychophagia-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Pediatr Dermatol 2012;29:488-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Joubert CE. Associations of social personality factors with personal habits. Psychol Rep 1995;76:1315-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Alkiewicz J. Uber onychotillomania. Dermatol Wochenschr 1934;98:519-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Pacan P, Grzesiak M, Reich A, Kantorska-Janiec M, Szepietowski JC. Onychophagia and onychotillomania: Prevalence, clinical picture and comorbidities. Acta Derm Venereol 2014;94:67-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Grzesiak M, Pacan P, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Onychotillomania in the course of depression: A case report. Acta Derm Venereol 2014;94:745-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Pacan P, Grzesiak M, Szepietowski J. Onychophagia and onychotillomania. Dermatol Prakt 2009;4:9-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Inglese M, Haley HR, Elewski BE. Onychotillomania: 2 case reports. Cutis 2004;73:171-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Lin YC, Lin YC. Onychotillomania, major depressive disorder and suicide. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31:597-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Ameen Sait M, Reddy BS, Garg BR. Onychotillomania 2 case reports. Dermatologica 1985;171:200-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Perrin AJ, Lam JM. Habit-tic deformity. CMAJ 2014;186:371.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Ring DS. Inexpensive solution for habit-tic deformity. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:1222-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Haneke E. Autoaggressive nail disorders. Dermatol Rev Mex 2013;57:225-34.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Wu JJ. Habit tic deformity secondary to guitar playing. Dermatol Online J 2009;15:16.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Vittorio CC, Phillips KA. Treatment of habit-tic deformity with fluoxetine. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:1203-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Bate KS, Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson ET, Bhullar N. The efficacy of habit reversal therapy for tics, habit disorders, and stuttering: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:865-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Haneke E. Management of the aging nail. J Womens Health Care 2014;3:204.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Freyschmidt-Paul P, Hoffmann R, Happle R. Trichoteiromania. Eur J Dermatol 2001;11:369-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Michopoulos I, Gournellis R, Papadopoulou M, Plachouras D, Vlahakos DV, Tournikioti K, et al. Acase of autophagia: A man who was mutilating his fingers by biting them. J Nerv Ment Dis 2012;200:183-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Baran R, Moulin G. The bidet nail: A French variant of the worn-down nail syndrome. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:377.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Dogra S, Yadav S. What's new in nail disorders? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:631-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Rigopoulos D, Charissi C, Belyayeva-Karatza Y, Gregoriou S. Lacquer nail. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:1153-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Ghanizadeh A, Derakhshan N, Berk M. N-acetylcysteine versus placebo for treating nail biting, a double blind randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem 2013;12:223-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Leonard HL, Lenane MC, Swedo SE, Rettew DC, Rapoport JL. A double-blind comparison of clomipramine and desipramine treatment of severe onychophagia (nail biting). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:821-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 52. |

Ravindran AV, da Silva TL, Ravindran LN, Richter MA, Rector NA. Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders: A review of the evidence-based treatments. Can J Psychiatry 2009;54:331-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 53. |

Sharma V, Sommerdyk C. Lithium treatment of chronic nail biting. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2014;16. pii: PCC.13l01623.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 54. |

Wadden P, Pawliuk G. Cessation of nail-biting and bupropion. Can J Psychiatry 1999;44:709-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 55. |

Koritzky G, Yechiam E. On the value of nonremovable reminders for behavior modification: An application to nail-biting (onychophagia). Behav Modif 2011;35:511-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 56. |

Moritz S, Treszl A, Rufer M. A randomized controlled trial of a novel self-help technique for impulse control disorders: A study on nail-biting. Behav Modif 2011;35:468-85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 57. |

Long ES, Miltenberger RG, Ellingson SA, Ott SM. Augmenting simplified habit reversal in the treatment of oral-digital habits exhibited by individuals with mental retardation. J Appl Behav Anal 1999;32:353-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 58. |

Silber KP, Haynes CE. Treating nailbiting: A comparative analysis of mild aversion and competing response therapies. Behav Res Ther 1992;30:15-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

36,465

PDF downloads

3,633