Translate this page into:

Newer insights in teledermatology practice

Correspondence Address:

Garehatty Rudrappa Kanthraj

Sri Mallikarjuna Nilaya, HIG 33, Group 1, Phase 2, Hootagally KHB Extension, Mysore - 570 018, Karnataka

India

| How to cite this article: Kanthraj GR. Newer insights in teledermatology practice. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:276-287 |

Abstract

The study and practice of dermatology care using interactive audio, visual, and data communications from a distance is called teledermatology. A teledermatology practice (TP) provides teleconsultation as well tele-education. Initially, dermatologists used videoconference. Convenience, cost-effectiveness and easy application of the practice made "store and forward" to emerge as a basic teledermatology tool. The advent of newer technologies like third generation (3G) and fourth generation (4G) mobile teledermatology (MT) and dermatologists' interest to adopt tertiary TP to pool expert (second) opinion to address difficult-to-manage cases (DMCs) has resulted in a rapid change in TP. Online discussion groups (ODGs), author-based second opinion teledermatology (AST), or a combination of both are the types of tertiary TP. This article analyzes the feasibility studies and provides latest insight into TP with a revised classification to plan and allocate budget and apply appropriate technology. Using the acronym CAP-HAT, which represents five important factors like case, approach, purpose, health care professionals, and technology, one can frame a TP. Store-and-forward teledermatology (SAFT) is used to address routine cases (spotters). Chronic cases need frequent follow-up care. Leg ulcer and localized vitiligo need MT while psoriasis and leprosy require SAFT. Pigmented skin lesions require MT for triage and combination of teledermoscopy, telepathology, and teledermatology for diagnosis. A self-practising dermatologist and national health care system dermatologist use SAFT for routine cases and a combination of ASTwith an ODG to address a DMC. A TP alone or in combination with face-to-face consultation delivers quality care.Introduction

The study and practice of dermatology using interactive audio, visual, and data communications from a distance is teledermatology. [1] A teledermatology tool refers to the technology or modality used to deliver dermatology care. The application of teledermatology tool (technology) to deliver dermatology care is called teledermatology practice [2] (TP). The aim of TP is to reach the unreached for dermatology care in remote geographic regions. It involves good general practitioner (GP) and dermatologist interaction. In recent times, with the advent of tertiary TP for difficult-to-manage cases (DMC), the scope of TP has widened. There is a specialist-to-specialist interaction for second opinion and continuing medical education that updates a dermatologist.

History of Teledermatology

In 1906, Wilhelm Einthoven discovered telecardiogram [3] and was successful in the transmission of electrocardiogram using a telephone network. The Nebraska Project, [4] USA, in 1959, used videoconference (VC) for psychiatry patients which was conducted between two hospitals within a distance of 150 kilometers. Between 1960 and 1970, research to monitor astronauts′ heart rate, blood pressure and electrocardiogram was conducted. [5] The term teledermatology was introduced by Prednia and Brown. [1] Teledermatology in a nursing home setting was first demonstrated by Zelickson and Homan. [6]

The advent of Medline and online reprint request, teledermoscopy, mobile teledermoscopy, telepathology, revolution and advancement in 3G and 4G mobile teledermatology (MT), and tertiary teledermatology like online discussion group (ODG) and author-based second opinion teledermatology (AST) has revolutionized TP.

TP is performed everywhere including as far as South Pole, [7] as remote as Faroe Islands, [8] rural India, [9] USA, [10] Africa, [11] in austere environments, [12] and nursing home settings. [13] A double-blind randomized control trial provides evidence for a therapeutic response of a drug. Similarly, the feasibility studies provide evidence regarding the application of teledermatology tools and play a key role to determine the TP.

TP reduces frequent visits, travel, and waiting period and minimizes the treatment cost. [14] It is important in elderly who suffer from chronic conditions like psoriasis and leg ulcer that call for frequent follow-up care. TP can be used in national health programs [2] to screen for leprosy and melanoma. TP helps in counseling and in initial examination prior to dermatosurgery. [15] TP facilitates to pool expert opinions and helps in continuing medical education. [16]

Poor net connectivity, poor image quality, and lack of referral proforma data can limit TP. [17] Legal issues, absence of in-person examination, varied treatment protocols between countries, doubts regarding the technology to offer second opinion can interfere with tertiary TP. [18] Time constraints, unavailability of the patient and doctor at the same time or the longer time taken to opine on still images, and patient discomfort in front of the camera, especially so for private part lesions, may limit TP. [14]

Importance and Need of the Teledermatology Practice Classification

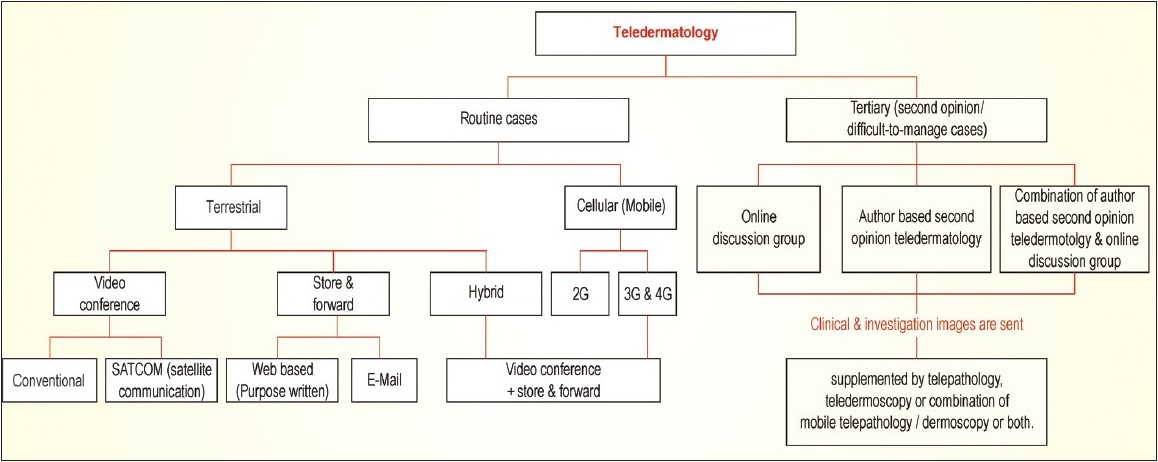

A systematic classification is required to conduct study and research, and plan and allocate budget. [2] TP tools are broadly categorized [14],[16] as data sent as 1) motion images, VC; (2) static images, store-and-forward teledematology (SAFT); (3) and a combination of both static and motion images, hybrid teledermatology (HT). The above tools are called stationary TP tools. [16] Later in 2004, Braun [19] from Sweden introduced MT for the management of leg ulcer. In 2008, the classification of TP was proposed. [2] It is based on technology, health care professionals involved in teleconsultation, and special area of teledermatology application like teledermoscopy and telepathology. [2] Recent advances in tertiary teledermatology and 3G/4G MT which were not in the earlier classification [2] are now incorporated in the proposed revised classification [Figure - 1]. TP tools are broadly divided into (a) basic TP to address the regular dermatology cases and (b) tertiary TP for DMCs to seek second opinion. Special areas of application include teledermoscopy, mobile teledermoscopy, telepathology, or their combination, placed in tertiary teledermatology, as it requires special expertise in the field to diagnose or offer second opinion.

|

| Figure 1: Classification of teledermatology practice |

Basic/Routine TP Tool

Stationary TP tools

Store-and-forward teledermatology

Static images of clinical and histopathological data are accessed anytime and anywhere. They are transferred from a GP to a specialist to deliver the management. A diagnosis agreement of 68%, [20] 89%, [21] 58%, [22] and 48% [17] has been documented. Recently, various feasibility studies have confirmed a good diagnostic accuracy when SAFT is compared to face-to-face consultation, [23] skin neoplasms, [24] and pediatric dermatology. [25] Dermatology cases that can be diagnosed by face-to-face examinations (spotters) have a good diagnostic accuracy by SAFT. Good quality images are taken by the GP in a short time. [26] The comparison between the clinical dermatologist and teledermatologist reveals that there is a small difference in the interobserver accuracy of SAFT for diagnostic accuracy, histopathological analysis (gold standard), and management plan for skin neoplasms. [24] A diagnostic agreement and management plan is good and teledermatology benefits remote geographic regions. [27] SAFT has a good diagnostic concordance for fever with rash in children. [28] SAFT is cheap, and easy to set up and practice. It is the commonest teledermatology tool as most of the cases are dealt and often regarded as a basic model for a TP. [2]

Videoconference

It is a live or interactive teledermatology. GP, patient and specialist interact with one another. Various feasibility studies [29],[30] have confirmed good diagnostic accuracy when VC is compared to face-to-face consultation. VC needs appropriate equipment and it is very expensive. Motion images are transmitted using satellite communication [5],[31],[32] (SATCOM) from a referral hospital to a remote region. A bus or a van mounted with a satellite communication travels to the camp destination region and establishes the connectivity with a tertiary center to conduct skin camps in rural India. Indian space research organization provides infrastructure. [31]

Hybrid teledermatology

This is a combination of both VC and SAFT to overcome the shortcomings faced when either of them is used individually. [33] Intercomparison of VC, SAFT, and HT [2],[24],[27],[29],[34],[35] reveals a face-to-face interaction in VC and HT, that is absent in SAFT. Good patient and physician satisfaction along with good diagnostic accuracy is achieved in all. The simultaneous presence of a health care professional is required in VC and HT and his or her presence may not be required in SAFT. SAFT is the most cost-effective and convenient TP tool compared to VC. The time taken for consultation is least for SAFT and more in VC and HT. Motion images are used in VC, still images are used in SAFT, and both the types of images are used in HT. Intraobserver reliability is very high in teledermatology. A hybrid system with audio is no better than SAFT alone. [35] The comparison of in-person examination, with VC and SAFT, revealed a comparable diagnostic and management agreement plan. Higher dermatologist confidence with in-person examination compared to either SAFT or VC is observed. Dermatologist confidence in SAFT and VC did not differ statistically from each other. [34] A randomized prospective outcome study demonstrated SAFT results in an equivalent clinical outcome compared with a conventional clinic-based consultation. [35]

Mobile teledermatology

The term cellular teledermatology is avoided and MT should be used instead as this term represents the transmission of images via mobile phones [19],[36] as well as through personal digital assistants. [37] Motion and still images are transferred using cellular phones. Images of leg ulcers are transferred from a digital camera to a computer system or a cellular phone. [19] Patients with a leg ulcer, nurses, or health care workers send periodic images from a remote area to a dermatologist. Treatment is offered and follow-up is performed periodically. Cost, travel, and time are saved. Various feasibility studies [38],[39] have confirmed a good diagnostic accuracy when MT is compared with face-to-face consultation.

Teledermatopathology

Transmission of histopathological images of skin using information technology for expert opinion is called teledermatopathology. [40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45] Teledermatopathology is achieved by (i) video-image (dynamic) analysis; (ii) store and forward (static); and (iii) web-based virtual slide system. [46] A virtual slide system is a recently developed technology where a robotic microscope is used; any field of the specimen is selected for better digitalization at any required magnification at the discretion of the dermatopathologist. [43]

Teledermoscopy

Pigmented skin lesions and melanoma are analyzed based on the dermoscopic criteria [47],[48] that depend on characteristic changes in epidermis and dermis. Dermoscopy images [49],[50],[51],[52],[53] are transmitted for expert opinion using routine TP tools like SAFT or tertiary TP for second opinion. If these images are transferred using mobile technology, it is called mobile teledermoscopy. Pigmentary skin lesions are screened by MT. [54]

Tertiary TP

DMCs need second opinion using information technology from one or more experts to provide dermatology care. It is referred as second opinion or tertiary TP. Expert opinion, resident training, and continuing medical education are the objectives of tertiary TP. [55] Previous reviews [2],[55] suggest SAFT and HT for second opinion TP. Currently, there are three types of tertiary TP: (a) ODG, [56],[57],[58],[59],[60],[61],[62] (b) AST, [18] (c) and the combination of ODG and AST [63] [Figure - 1].

Online discussion groups

DMCs are a challenge to the health care system. An ODG is formed with a group of dermatologists who share constructive suggestions [56],57],[58] for a submitted case. Feasibility studies have confirmed 81% concordance with face-to-face consultation. [58] Members of academic societies like Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists have formed an ODG at ACAD_IADVL@yahoogroups.com (an e-mail group) and participate in regular academic discussions. Telederm.org, [56] Rxderm, [57] Virtual Grand Rounds in Dermatology, [59] and Black Skin Dermatology Online [60] are the examples of ODGs. Experts may be unavailable for an instant case, or dermatologists and allied research workers who might have carried out research involving a DMC may not have registered at the site and at times consensus may not be reached for a case without these experts. These limitations of ODG are overcome by AST. [18] Online blogs are another form of ODGs.

Author-based second opinion teledermatology

Experts who have previously worked and published may offer valuable suggestions for a DMC. A dermatologist performs a PubMed survey, notes author′s e-mail, obtains the literature, reads, analyzes, and obtains constructive suggestions for both the case and related literature from the author. This process updates the physician and delivers quality health care.

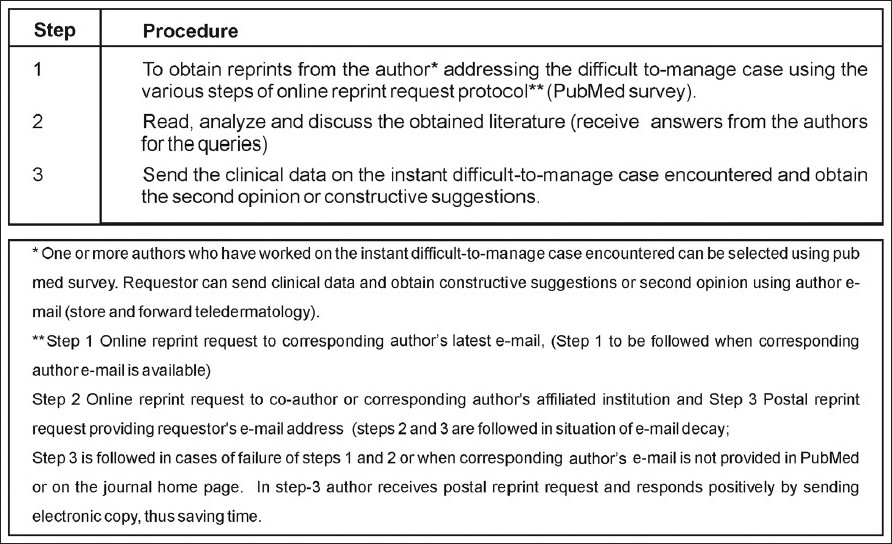

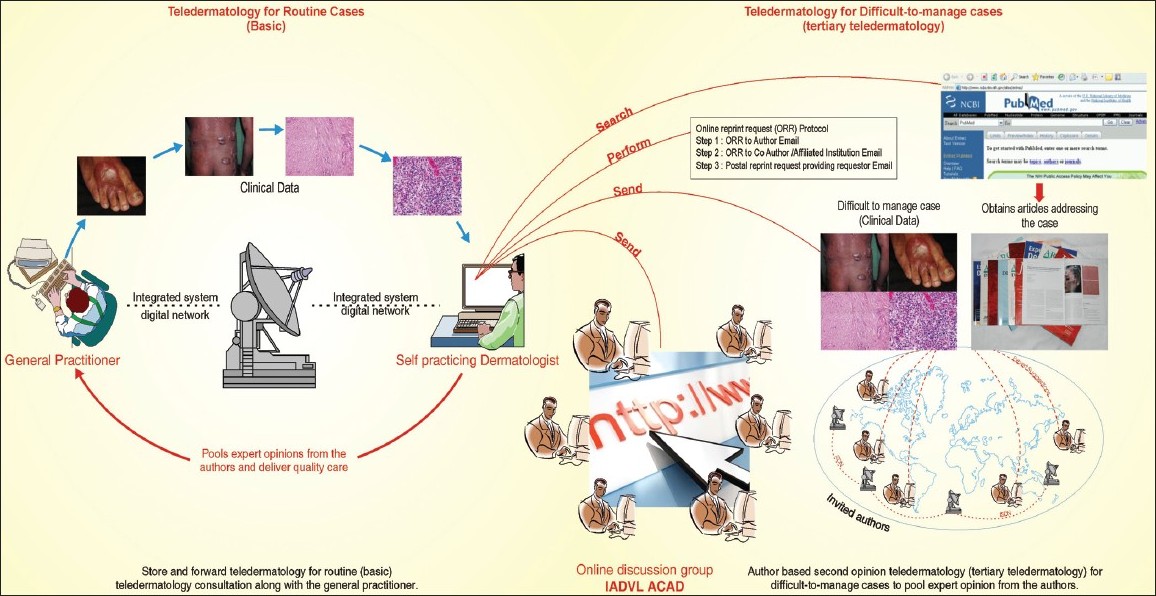

Steps involved in AST are summarized in [Figure - 2]. A recent online author survey [18] observed that the author who has previously worked and published on the instant case offers constructive suggestions; quality of opinion is excellent as opinions are pooled from experts who have done original work. Evidence-based medical practice is followed. [18]

|

| Figure 2: The steps involved in author-based second opinion teledermatology |

The limitations of ODGs are overcome by enrolling the experts. In special situations, the moderator apart from offering suggestions invites second opinion from the author who has published the relevant work on an instant case and the moderator can pool and summarize collective opinions and offer constructive suggestions based on the literature. Evidence-based medicine is thereby practised. Time taken in an ODG to answer the requests were rapid: 80 (60%) of the requests of the ODG group were answered within 1 day. [61] The exact time needed for AST has not been reported yet; however, reprint requests sent to dermatology authors have been responded (63%) to positively and rapidly in <2 days. [64]

Implementation of TP (applied teledermatology)

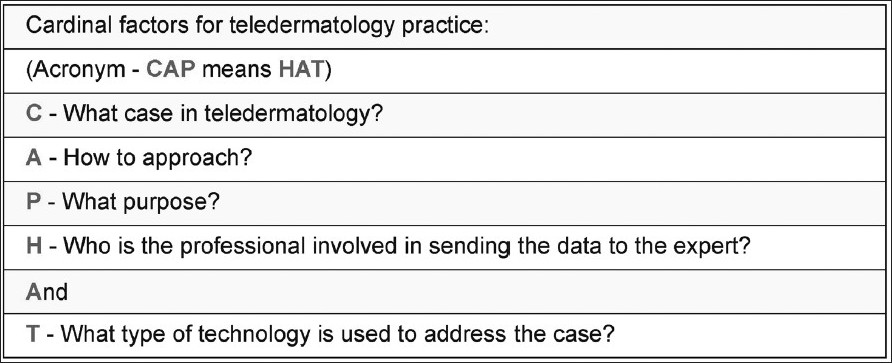

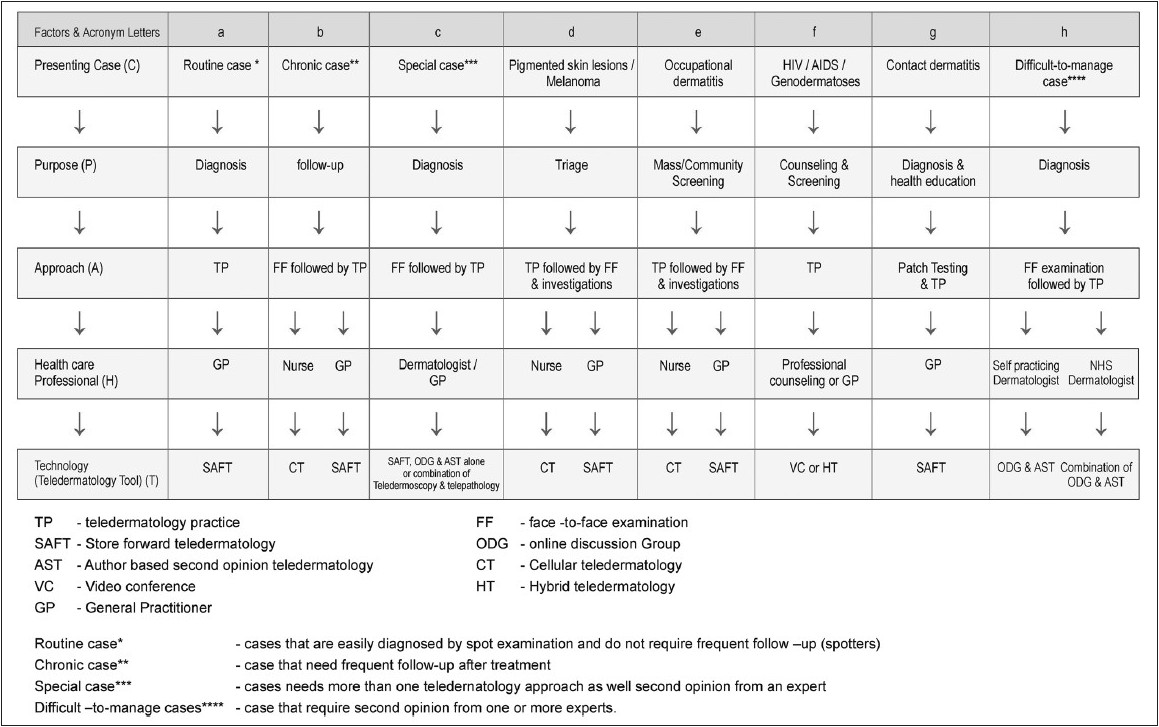

There are five important factors that determine the appropriate teledermatology tools to be used in TP. The acronym "CAP-HAT" represents these factors - case, approach, purpose, health care professionals, and teledermatology tool [63] (technology). The letters used in the acronym and the five important factors that determine TP are shown in [Figure - 3]. It is important to assess the utility before an acronym is introduced. [65] The application and utility of the acronym CAP-HAT in TP is summarized in [Figure - 4]. The sequence of letters "A" and "P" in the acronym "CAP-HAT′ is interchanged for convenience.

|

| Figure 3: The acronym "CAP-HAT" represents as cardinal factors to design a teledermatology practice. The two words in the acronym "CAP" and "HAT" are related as thesaurus and therefore the acronym is represented as "CAP-HAT." and it is easy to remember and reproduce. The repeated letter "A" in the acronym does not refer to any factor; it is a conjunction ("and"). that links the fifth factor "technology" |

|

| Figure 4: The feasibility studies in teledermatology practice. This table is derived by analyzing the feasibility studies with respect to the five cardinal factors, represented as an acronym CAP-HAT. The sequence of letters "A" and "P" in the acronym "CAP-HAT" are interchanged for convenience. The references for feasibility studies are shown in the parentheses: (a) regular cases (23-25), (b) chronic disease: diagnosis and follow-up care (68-73, 75-76), (c) special case (cutaneous neoplasm) diagnosis (77, 78), (d) triage (80-87), (e) screening or mass survey or occupational dermatitis (89-91), (f) education and counseling (63, 85-88, 92-95), (g) investigation (89-91), (h) difficult-to-manage cases (56-63) |

Certain dermatological conditions may be chronic with periodic remissions and exacerbations. They need a longer and frequent follow-up care using SAFT. [66],[67] Diagnosis [68],[69],[70] and follow-up care [71],[72],[73] are provided by initial face-to-face consultation followed by TP. Hansen′s disease, [68] leg ulcer, [69],[70],[71] psoriasis, [72] and acne [73] diagnosis and follow-up care are monitored using MT or SAFT [[Figure - 4]b]. These studies have confirmed that delivering follow-up care via SAFT produces clinical outcomes equivalent to face-to-face consultation [[Figure - 4]b].

Nurse or health care workers can send in periodic images using MT. [74] GP can send images to the dermatologist and use SAFT [74] [[Figure - 4]b]. A nurse or a patient send images, and psoriasis severity can be evaluated using MT. [32],[72] Patient empowerments in teledermatology to deliver follow-up care in chronic dermatology cases like psoriasis, [72] acne, [73] and leg ulcer [71] are documented. A compliance management system using MT for the periodic assessment of psoriasis is proposed. [75] MT text messages are innovative, low cost, and a reminder tool to improve adherence to treatment. [76] A National Health Care System (NHS) should implement text messages addressing adherence to treatment, education, and awareness especially for diseases like leprosy covered by national health programs. This process provides education and builds confidence in patients. Medical treatment and/or dermatosurgical counseling or follow-up care for vitiligo is delivered. [15]

Diagnosis and management of melanoma and pigmented skin lesions are challenging and require initial face-to-face examination followed by TP with more than one teledermatology tool. [58],[77] SAFT with ODGs and AST or in combination with telepathology, teledermoscopy, and or mobile teledermoscopy is of additive value with an improved diagnostic accuracy [78],[79] compared to face-to-face examination and facilitates second opinion [63] [[Figure - 4]c].

Nurses or trained health care workers triage pigmented skin lesions [77],[78],[79],[80],[81],[82],[83],[84],[85],[86],[87] or survey or mass screen the cases using MT and can send in images directly to the tertiary center for histopathological examination or route the images through a GP [[Figure - 4]d]. Infectious cases are diagnosed by SAFT. [88] Screening for occupational eczema is performed using SAFT. [89] The evaluation of the scoring system for hand eczema is feasible for SAFT. [90] To screen or triage melanoma, pigmented skin lesions, leprosy, and endemic cases like leishmaniasis, one can adapt initial TP followed by face-to-face examination. In routine practice, nurses use MT and GPs use SAFT to triage cases and provide further management in a tertiary center [[Figure - 4]e]. The interpretation of patch testing is performed by SAFT [91] [[Figure - 4]g]. A dermatologist uses VC or HT for dermatology cases like HIV/AIDS and genodermatoses [[Figure - 4]f] that require counseling and health education. [92],[93],[94],[95]

The implementation of TP

The application of TP tools is reviewed here. [2],[96],[97],[98] An ideal TP should address routine cases as well as DMCs. A combination of (a) basic or routine and (b) tertiary TP are required to deliver complete TP. [63] Self-practicing dermatologists [99],[100],[101],[102] and NHS dermatologists [63],[103],[104],[105] use SAFT for routine practice. They use ODGs and AST to address DMCs [63] [[Figure - 4]h]. Self-practicing dermatologists organize TP with a group of known GPs from the region. They join the ODG formed by the national academic body, like Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists, and Leprologists (IADVL ACAD), for DMC and offer treatment [Figure - 5].

|

| Figure 5: The organization of teledermatology practice for a self-practicing dermatologist: It comprises a basic model SAFT, where a GP interacts with a dermatologist for regular cases (spotters) along with ODG and AST to obtain a second opinion on difficult-to-manage cases (modified with permission from Kanthraj GR. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010; 24:961-6. Authors' willingness for sencond opinion teledermatology in difficult to manage cases: 'An online survey' |

The Netherlands NHS [104] has successfully implemented SAFT for TP. Over 185 dermatologists and 2500 GPs performed 33,000 teledermatology consultations with reimbursement by the Dutch healthcare insurance system in a period of 4 years. [104] Recently, a TP model for a NHS is proposed. [63] In the Indian context, this model [63] can be applied in respective state and central government health services. Governments′ health service dermatologists form an ODG and among them two or more senior dermatologists are appointed as moderators by the health service. The NHS provides the information technology infrastructure. The moderator identifies DMCs, and offers and pools opinions either from experts within the ODG or AST. A dermatologist can submit or offer opinions for other submissions. This process enables a dermatologist to update recent advances, and earn CME credit and reimbursement. DMCs are not neglected in the community as debated earlier. Epidemiology data are maintained. House surgeons are trained for history taking, photography, and sending images for teleconsultation in rural areas. [105]

Cost-effective studies [106],[107],[108],[109],[110],[111] on implementation of TP have found it to be economical. A study on the economic evaluation of teledermatology reveals that SAFT is 1.6-fold cheaper when compared with the conventional letter referral system to triage skin cancer patients. [107] TP, if implemented appropriately [63] can deliver the quality care without any burden on the financial position of a NHS. A recent study from Netherlands [111] confirmed that TP is cost effective if the distance to a dermatologist is larger (≥75 km) or when more consultations (≥37%) are prevented by TP.

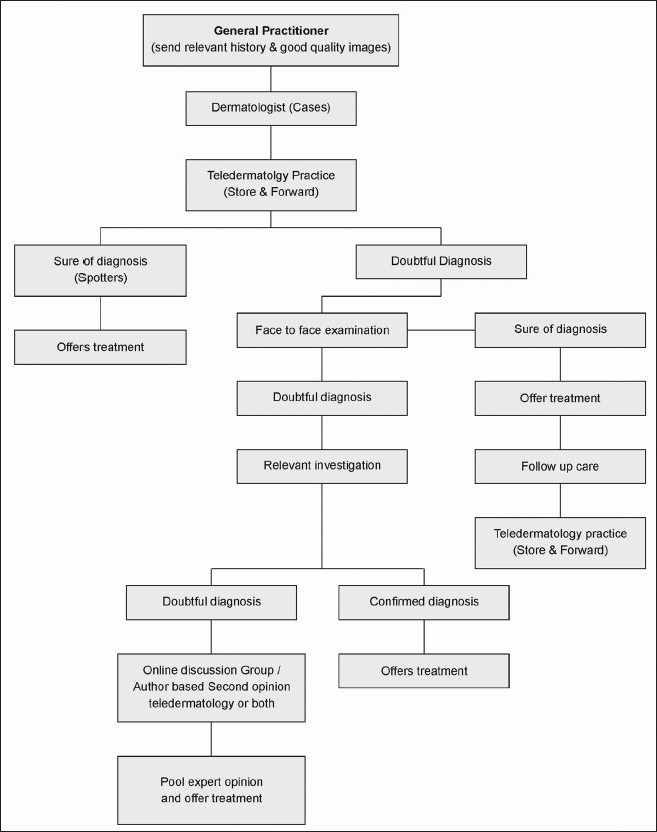

Face to face consultation versus TP

There is a debate to compare both face-to-face examination and TP. [112] Patients still prefer a face-to-face consultation, with one study reporting that 40% felt "something was missing" when the dermatologist was not seen in person. [112] A face-to-face examination binds the physician and patient and TP is not a substitute. Legal principles of face-to-face consultation will apply to TP. [14] Pooling expert opinions across the globe is a great advantage of a TP, that is difficult to achieve in a face-to-face consultation. Therefore, a combination of both face-to-face consultation and TP in appropriate situations as illustrated in [Figure - 6] can deliver quality care. This approach minimizes the shortcomings of either face-to-face examination or TP alone.

|

| Figure 6: Application of teledermatology practice and face-to-face consultation in appropriate clinical situation to deliver quality care: A dermatologists approach toward a case with a combination of both face-to-face and teledermatology practice or individually depending on appropriate clinical situations to deliver quality care and minimize the short comings of either face-to-face examination or teledermatology practice alone |

Teledermatology and Law

Privacy legislation in Australia has made access to the blogs possible, only by invitation. [85] No specific regulation exists till date for ODG, blogs, and AST where experts across the globe interact. Uniform international guidelines are required. In general, the practice principles of face-to-face examination apply for a TP. [14] The confidentiality and protection of images are important. [14]

Future Perspective in Teledermatology

The advent of the 3G/4G mobile teledermatology revolution has advanced to a point where they are as good as small computers. MT is basically changing into another method of SAFT and even VC with video-enabled smart phones [Figure - 1]. There are no feasibility studies yet; future studies in this area should expand this information. The widespread introduction of 3G /4G services in India and elsewhere will in all probability spark an increased use of advanced MT-based consultations.

Conclusion

An ideal TP should have a teledermatology tool that addresses regular cases as well as DMCs. A self-practicing dermatologist and a NHS dermatologist use SAFT for regular cases and adopt ODG, AST, or both for DMCs guided by moderators. Active survey (house-to-house) screening, pigmented skin lesions (melanoma), and leprosy require MT. Five factors determine the design of a TP. Feasibility studies have demonstrated the role of TP in various situations. TP alone or in combination with face-to-face consultation delivers quality care. Medical graduates, interns, and dermatology residents need encouragement to participate in TP as it updates their knowledge and it should be included in the teaching curriculum.

| 1. |

Perednia DA, Brown NA. Teledermatology: One application of telemedicine. Bull Med Libr Assoc.1995; 83:42- 47.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Kanthraj GR. Classification and design of teledermatology practice: What dermatoses? Which technology to apply? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:865-75.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Stanberry B. Telemedicine: Barriers and opportunities in the 21 st century. J Intern Med 2000;247:615-28.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Zundel K. Telemedicine: History, applications, and impact on librarianship. Bull Med Libr Assoc 1996;84:71-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Cipolat C, Geiges M. The history of telemedicine. Curr Probl Dermatol 2003;32:6-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Zelickson BD, Homan L. Teledermatology in the nursing home. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:171-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Sun A, Lanier R, Diven D. A review of the practices and results of the UTMB to South Pole teledermatology program over the past six years. Dermatol Online J 2010;16:16.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Dam TN, Vang E. Teledermatology on the Faroe Islands. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:891-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Feroze K. Teledermatology in India: Practical implications. Indian J Med Sci 2008;62:208-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Vallejos QM, Quandt SA, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Brooks T, Cabral G, et al. Teledermatology consultations provide specialty care for farmworkers in rural clinics. J Rural Health 2009;25:198-202.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Kaddu S, Soyer HP, Gabler G, Kovarik C. The Africa Teledermatology Project: Preliminary experience with a sub-Saharan teledermatology and e-learning program. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;61:155-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

McManus J, Salinas J, Morton M, Lappan C, Poropatich R. Teleconsultation program for deployed soldiers and healthcare professionals in remote and austere environments. Prehosp Disaster Med 2008;23:210-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Janardhanan L, Leow YH, Chio MT, Kim Y, Soh CB. Experience with the implementation of a web-based teledermatology system in a nursing home in Singapore. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:404-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Eedy DJ, Wootton R. Teledermatology: A review. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:696-707.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Kanthraj GR. Teledermatology: Its role in dermatosurgery. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2008;1:68-74.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Massone C, Wurm EM, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Soyer HP. Teledermatology: An update. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2008;27:101-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Mahendran R, Goodfield MJ, Sheehan-Dare RA. An evaluation of the role of a store-and-forward teledermatology system in skin cancer diagnosis and management. Clin Exp Dermatol 2005;30:209-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Kanthraj GR. Authors' willingness for second-opinion teledermatology in difficult-to-manage cases: 'An online survey'. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:961-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Braun RP, Vecchietti JL, Thomas L, Prins C, French LE, Gewirtzman AJ, et al. Telemedical wound care using a new generation of mobile telephones: A feasibility study. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:254-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Whited JD, Hall RP, Simel DL, Foy ME, Stechuchak KM, Drugge RJ, et al. Reliability and accuracy of dermatologists' clinic-based and digital image consultations. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:693-702.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

High WA, Houston MS, Calobrisi SD, Drage LA, McEvoy MT. Assessment of the accuracy of low-cost store and forward teledermatology consultation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:776-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Tucker WF, Lewis FA. Digital imaging: A diagnostic screening tool? Int J Dermatol 2005;44:479-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Pak H, Triplett CA, Lindquist JH, Grambow SC, Whited JD. Store-and-forward teledermatology results in similar clinical outcomes to conventional clinic-based care. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:26-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Warshaw EM, Gravely AA, Bohjanen KA, Chen K, Lee PK, Rabinovitz HS, et al. Interobserver accuracy of store and forward teledermatology for skin neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:513-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Chen TS, Goldyne ME, Mathes EF, Frieden IJ, Gilliam AE. Pediatric teledermatology: Observations based on 429 consults. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:61-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Berghout RM, Eminoviæ N, de Keizer NF, Birnie E. Evaluation of general practitioner's time investment during a store-and-forward teledermatology consultation. Int J Med Inform 2007;76:S384-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Levin YS, Warshaw EM. Teledermatology: A review of reliability and accuracy of diagnosis and management. Dermatol Clin 2009;27:163-76.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Heffner VA, Lyon VB, Brousseau DC, Holland KE, Yen K. Store-and-forward teledermatology versus in-person visits: a comparison in pediatric teledermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:956-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Wootton R, Blooomer SE, Corbet R, Eedy DJ, Hicks N, Lotery HE, et al. Multicenter randomized control trial comparing real time teledermatology with conventional outpatient dermatological care: Societal cost benefits analysis. BMJ 2000;320:1252-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Baba M, Seçkin D, Kapdaðli S. A comparison of teledermatology using store-and-forward methodology alone, and in combination with Web camera videoconferencing. J Telemed Telecare 2005;11:354-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Sathyamurthy LS, Bhaskaranarayana A. Telemedicine: Indian Space agency's (ISRO) initiatives for specialty health care delivery to remote and rural population. In: Sathyamurthy LS, Murthy RL, editors. Telemedicine manual-Guide book for practice of telemedicine, 1 st ed. Bangalore: Indian Space Research Organization, Department of space. Government of India; 2005. p. 9-13.

st ed. Bangalore: Indian Space Research Organization, Department of space. Government of India; 2005. p. 9-13.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Kanthraj GR, Srinivas CR. Store and forward teledermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:5-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Edison KE, Dyer JA. Teledermatology in Missouri and beyond. Mo Med 2007;104:139-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Edison KE, Ward DS, Dyer JA, Lane W, Chance L, Hicks LL. Diagnosis, diagnostic confidence, and management concordance in live-interactive and store-and-forward teledermatology compared to in-person examination. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:889-95.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Romero G, Sánchez P, García M, Cortina P, Vera E, Garrido JA. Randomized controlled trial comparing store-and-forward teledermatology alone and in combination with web-camera videoconferencing. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010;35:311-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Massone C, Lozzi GP, Wurm E, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Schoellnast R, Zalaudek I, et al. Cellular phones in clinical teledermatology. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:1319-20.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Massone C, Lozzi GP, Wurm E, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Schoellnast R, Zalaudek I, et al. Personal digital assistants in teledermatology. Br J Dermatol 2006;154:801-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Chung P, Yu T, Scheinfeld N. Using cellphones for teledermatology, a preliminary study. Dermatol Online J 2007;13:2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Ebner C, Wurm EM, Binder B, Kittler H, Lozzi GP, Massone C, et al. Mobile teledermatology: A feasibility study of 58 subjects using mobile phones. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:2-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Weinstein LJ, Epstein JI, Edlow D, Westra WH. Static image analysis of skin specimens: The application of telepathology to frozen section evaluation. Hum Pathol 1997;28:30-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Berman B, Elgart GW, Burdick AE. Dermatopathology via a still-image telemedicine system: Diagnostic concordance with direct microscopy. Telemed J 1997;3:27-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Okada DH, Binder SW, Felten CL, Strauss JS, Marchevsky AM. 'Virtual microscopy' and the Internet as telepathology consultation tools: Diagnostic accuracy in evaluating melanocytic skin lesions. Am J Dermatopathol 1999;21:525-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Piccolo D, Soyer HP, Burgdorf W, Talamini R, Peris K, Bugatti L, et al. Concordance between telepathologic diagnosis and conventional histopathologic diagnosis: A multiobserver store-and-forward study on 20 skin specimens. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:53-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Weinstein RS, Descour MR, Liang C, Barker G, Scott KM, Richter L, et al. An array microscope for ultrarapid virtual slide processing and telepathology. Design, fabrication, and validation study. Hum Pathol 2004;35:1303-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Massone C, Peter Soyer H, Lozzi GP, Di Stefani A, Leinweber B, Gabler G, et al. Feasibility and diagnostic agreement in teledermatopathology using a virtual slide system. Hum Pathol 2007;38:546-54.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Massone C, Brunasso AM, Campbell TM, Soyer HP. State of the art of teledermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol 2008;30:446-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Massone C, DiStefani A, Soyer HP. Dermoscopy for skin cancer detection. Curr Opin Oncol 2005;17:147-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Carli P, de Giorgi V, Chiarugi A, Nardini P, Weinstock MA, Crocetti E, et al. Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: A randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;50:683-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Leinweber B, Massone C, Kodama K, Kaddu S, Cerroni L, Haas J, et al. Teledermatopathology: A controlled study about diagnostic validity and technical requirements for digital transmission. Am J Dermatopathol 2006;28:413-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Piccolo D, Smolle J, Wolf IH, Peris K, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Dell'Eva G, et al. Face-to-face diagnosis vs. telediagnosis of pigmented skin tumors: A teledermoscopic study. Arch Dermatol 1999;135:1467-71.

et al. Face-to-face diagnosis vs. telediagnosis of pigmented skin tumors: A teledermoscopic study. Arch Dermatol 1999;135:1467-71.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Argenziano G, Soyer HP. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: A valuable tool for early diagnosis of melanoma. Lancet Oncol 2001;2:443-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 52. |

Piccolo D, Smolle J, Argenziano G, Wolf IH, Braun R, Cerroni L, et al. Teledermoscopy-results of a multicenter study on 43 pigmented skin lesions. J Telemed Telecare 2000;6:132-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 53. |

Moreno-Ramirez D, Ferrandiz L, Nieto-Garcia A, Carrasco R, Moreno-Alvarez P, Galdeano R, et al. Store-and-forward teledermatology in skin cancer triage. Experience and evaluation of 2009 teleconsultations. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:479-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 54. |

Massone C, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Ahlgrimm-Siess V, Gabler G, Ebner C, Soyer HP. Melanoma screening with cellular phones. PLoS One 2007;2:e483.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 55. |

van der Heijden JP, Spuls PI, Voorbraak FP, de Keizer NF, Witkamp L, Bos JD. Tertiary teledermatology: A systematic review. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:56-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 56. |

Soyer HP, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Massone C, Gabler G, Dong H, Ozdemir F, et al. Telederm.org: Freely available online consultations in dermatology. PLoS Med 2005;2:e87.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 57. |

Huntley AC, Smith JG. New communication between dermatologists in the age of the Internet. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2002;21:202-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 58. |

Lozzi GP, Soyer HP, Massone C, Micantonio T, Kraenke B, Fargnoli MC, et al. The additive value of second opinion teleconsulting in the management of patients with challenging inflammatory, neoplastic skin diseases: A best practice model in dermatology? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:30-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 59. |

Hu SW, Foong HB, Elpern DJ. Virtual Grand Rounds in Dermatology: An 8-year experience in web-based teledermatology. Int J Dermatol 2009;48:1313-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 60. |

Ezzedine K, Amiel A, Vereecken P, Simonart T, Schietse B, Seymons K, et al. Black Skin Dermatology Online, from the project to the website: A needed collaboration between North and South. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;22:1193-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 61. |

Massone C, Soyer HP, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Di Stefani A, Lozzi GP, Gabler G, et al. Two years' experience with Web-based teleconsulting in dermatology. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12:83-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 62. |

Pak HS, Welch M, Poropatich R. Web-based teledermatology consult system: Preliminary results from the first 100 cases. Stud Health Technol Inform 1999;64:179-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 63. |

Kanthraj GR. A teledermatology practice model for a national healthcare system: Proposal and recommendations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:616-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 64. |

Kanthraj GR. Online reprint request and dermatology literature: A feasibility study. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;35:196-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 65. |

Patel CB, Rashid RM. Averting the proliferation of acronymophilia in dermatology: Effectively avoiding ADCOMSUBORDCOMPHIBSPAC. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:340-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 66. |

Knol A, van den Akker TW, Damstra RJ, de Haan J. Teledermatology reduces the number of patient referrals to a dermatologist. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12:75-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 67. |

Chanussot-Deprez C, Contreras-Ruiz J. Telemedicine in wound care. Int Wound J 2008;5:651-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 68. |

Trindade MA, Wen CL, Neto CF, Escuder MM, Andrade VL, Yamashitafuji TM, et al. Accuracy of store-and-forward diagnosis in leprosy. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:208-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 69. |

Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Salmhofer W, Binder B, Okcu A, Kerl H, Soyer HP. Feasibility and acceptance of telemedicine for wound care in patients with chronic leg ulcers. J Telemed Telecare 2006;1:15-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 70. |

Salmhofer W, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Gabler G, Rieger-Engelbogen K, Gunegger D, Binder B, et al. Wound teleconsultation in patients with chronic leg ulcers. Dermatology 2005;210:211-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 71. |

Binder B, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Salmhofer W, Okcu A, Kerl H, Soyer HP. Teledermatological monitoring of leg ulcers in cooperation with home care nurses. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:1511-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 72. |

Frühauf J, Schwantzer G, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Weger W, Ahlgrimm-Siess V, Salmhofer W, et al. Pilot study using teledermatology to manage high-need patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:200-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 73. |

Watson AJ, Bergman H, Williams CM, Kvedar JC. A randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of online follow-up visits in the management of Acne. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:406-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 74. |

van den Akker TW, Reker CH, Knol A, Post J, Wilbrink J, van der Veen JP. Teledermatology as a tool for communication between general practitioners and dermatologists. J Telemed Telecare 2001;7:193-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 75. |

Schreier G, Hayn D, Kastner P, Koller S, Salmhofer W, Hofmann-Wellenhof R. A mobile-phone based teledermatology system to support self-management of patients suffering from psoriasis. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2008;2008:5338-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 76. |

Armstrong AW, Watson AJ, Makredes M, Frangos JE, Kimball AB, Kvedar JC. Text-message reminders to improve sunscreen use: A randomized, controlled trial using electronic monitoring. Arch Dermatol 2009;145:1230-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 77. |

Hsiao JL, Oh DH. The impact of store-and-forward teledermatology on skin cancer diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:260-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 78. |

Di Stefani A, Zalaudek I, Argenziano G, Chimenti S, Soyer HP. Feasibility of a two-step teledermatologic approach for the management of patients with multiple pigmented skin lesions. Dermatol Surg 2007;33:686-92.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 79. |

Ferrara G, Argenziano G, Cerroni L ,Cusano F, Di Blasi A, Urso C, et al. A pilot study of a combined dermascopic-pathological approach to the telediagnosis of melanocytic skin neoplasms. J Telemed Telecare 2004;10:34-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 80. |

Massone C, Brunasso AM, Campbell TM, Soyer HP. Mobile teledermoscopy-melanoma diagnosis by one click? Semin Cutan Med Surg 2009;28:203-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 81. |

May C, Giles L, Gupta G. Prospective observational comparative study assessing the role of store and forward teledermatology triage in skin cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol 2008;33:736-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 82. |

Moreno-Ramirez D, Ferrandiz L, Nieto-Garcia A, Carrasco R, Moreno-Alvarez P, Galdeano R, et al. Store-and-forward teledermatology in skin cancer triage: Experience and evaluation of 2009 teleconsultations. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:479-86.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 83. |

Moreno-Ramirez D, Ferrandiz L, Galdeano R, Camacho FM. Teledermatoscopy as a triage system for pigmented lesions: A pilot study. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31:13-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 84. |

Moreno-Ramirez D, Ferrandiz L, Bernal AP, Duran RC, Martín JJ, Camacho F. Teledermatology as a filtering system in pigmented lesion clinics. J Telemed Telecare 2005;11:298-303.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 85. |

Massone C, Brunasso AM, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Gulia A, Soyer HP. Teledermoscopy: Education, discussion forums, teleconsulting and mobile teledermoscopy. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2010;145:127-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 86. |

Shapiro M, James WD, Kessler R, Lazorik FC, Katz KA, Tam J, et al. Comparison of skin biopsy triage decisions in 49 patients with pigmented lesions and skin neoplasms: Store-and-forward teledermatology vs face-to-face dermatology. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:525-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 87. |

Tan E, Yung A, Jameson M, Oakley A, Rademaker M. Successful triage of patients referred to a skin lesion clinic using teledermoscopy (IMAGE IT trial). Br J Dermatol 2010;162:803-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 88. |

Caumes E, Le Bris V, Couzigou C, Menard A, Janier M, Flahault A. Dermatoses associated with travel to Burkina Faso and diagnosed by means of teledermatology. Br J Dermatol 2004;150:312-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 89. |

Baumeister T, Weistenhöfer W, Drexler H, Kütting B. Prevention of work- related skin diseases: Teledermatology as an alternative approach in occupational screenings. Contact Dermatitis 2009;61:224-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 90. |

Baumeister T, Weistenhöfer W, Drexler H, Kötting B. Spoilt for choice--evaluation of two different scoring systems for early hand eczema in teledermatological examinations. Contact Dermatitis 2010;62:241-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 91. |

Ivens U, Serup J, Ogoshi K. Allergy patch test reading from photographic images. disagreement on ICDRG grading but agreement on simplified tripartite reading. Skin Res Technol 2007;13:110-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 92. |

Wahlgren CF, Edelbring S, Fors U, Hindbeck H, Stahle M. Evaluation of an interactive case simulation system in dermatology and venereology for medical students. BMC Med Educ 2006;6:40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 93. |

Shaikh N, Lehmann CU, Kaleida PH, Cohen BA. Efficacy and feasibility of teledermatology for paediatric medical education. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:204-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 94. |

Qureshi AA, Brandling-Bennett HA, Giberti S, McClure D, Halpern EF, Kvedar JC. Evaluation of digital skin images submitted by patients who received practical training or an online tutorial. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12:79-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 95. |

Wurm EM, Campbell TM, Soyer HP. Teledermatology: How to start a new teaching and diagnostic era in medicine. Dermatol Clin 2008;26:295-300.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 96. |

Eminoviæ N, de Keizer NF, Bindels PJ, Hasman A. Maturity of teledermatology evaluation research: A systematic literature review. Br J Dermatol 2007;156:412-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 97. |

Whited JD. Teledermatology research review. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:220-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 98. |

Ferguson J. How to do a telemedical consultation. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12:220-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 99. |

Glaessl A, Schiffner R, Walther T, Landthaler M, Stolz W. Are dermatologists in private practice interested in teledermatological services? Stud Health Technol Inform 1999;64:185-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 100. |

Zelickson BD. Teledermatology in the nursing home. Curr Probl Dermatol 2003;32:167-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 101. |

Mallett RB. Teledermatology in practice. Clin Exp Dermatol 2003;28:356-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 102. |

Eminoviæ N, Witkamp L, Ravelli AC, Bos JD, van den Akker TW, Bousema MT, et al . Potential effect of patient-assisted teledermatology on outpatient referral rates. J Telemed Telecare 2003;9:321-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 103. |

Norum J, Pedersen S, Størmer J, Rumpsfeld M, Stormo A, Jamissen N, et al. Prioritisation of telemedicine services for large scale implementation in Norway. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:185-92.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 104. |

van der Heijden J. Teledermatology integrated in the Dutch national healthcare system. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:615-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 105. |

Silva CS, Souza MB, Duque IA, de Medeiros LM, Melo NR, Araújo Cde A, et al. Teledermatology: Diagnostic correlation in a primary care service. An Bras Dermatol 2009;84:489-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 106. |

Pak HS, Datta SK, Triplett CA, Lindquist JH, Grambow SC, Whited JD. Cost minimization analyses of a store-and-forward teledermatology consult system. Telemed J E Health 2009;15:160-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 107. |

Moreno-Ramirez D, Ferrandiz L, Ruiz-de-Casas A, Nieto-Garcia A, Moreno-Alvarez P, Galdeano R, et al. Economic evaluation of a store-and-forward teledermatology system for skin cancer patients. J Telemed Telecare 2009;15:40-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 108. |

Ferrándiz L, Moreno-Ramírez D, Ruiz-de-Casas A, Nieto-García A, Moreno-Alvarez P, Galdeano R, et al. An economic analysis of presurgical teledermatology in patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2008;99:795-802.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 109. |

Ferrandiz L, Moreno-Ramirez D, Nieto-Garcia A, Carrasco R, Moreno-Alvarez P, Galdeano R, et al. Teledermatology-based presurgical management for nonmelanoma skin cancer: A pilot study. Dermatol Surg 2007;33:1092-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 110. |

Whited JD. Economic Analysis of Telemedicine and the Teledermatology Paradigm. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:223-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 111. |

Eminovic N, Dijkgraaf MG, Berghout RM, Prins AH, Bindels PJ, de Keizer NF. A cost minimisation analysis in teledermatology: Model-based approach. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:251.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 112. |

Collins K, Bowns I, Walters S. General practitioners perceptions of asynchronous telemedicine in a randomized controlled trial of teledermatology. J Telemed Telecare 2004;10:94-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

6,397

PDF downloads

3,784