Translate this page into:

No association between seropositivity for Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus: A case control study

2 Departments of Pathology, School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata, India

3 Departments of Virology, School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata, India

4 Departments of Tropical Medicine, School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata, India

Correspondence Address:

Nandita Bhattacharya

AD- 64, Sector I, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700 064

India

| How to cite this article: Das A, Das J, Majumdar G, Bhattacharya N, Neogi DK, Saha B. No association between seropositivity for Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus: A case control study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:198-200 |

Abstract

Background: The epidemiological association of lichen planus (LP) with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been recorded from some countries and HCV RNA3 has been isolated from lesional skin in patients with LP and chronic HCV infection. The observed geographical differences regarding HCV infection and LP could be immuno-genetically related. Aim: To determine whether HCV has a causal relationship with LP. Methods: Histopathologically proved cases of LP were subjected to antibody to HCV test by the Third Generation Enzyme Immunoassay Kit for the detection of antibody to HCV (Anti-HCV) in human serum or plasma. They were routinely screened in the virology department by the reagent kit, HIVASE 1 + 2, adopting the "direct sandwich principle" for the assay to detect antibodies to HIV-1 and/or HIV-2. There were 150 age and sex matched controls (not suffering from LP) and HIV-I and II negative, and negative for HCV. Results: Of the 104 patients studied only 2 patients (1.92%) of generalized LP with disease duration of more than 3 months were found to be positive for antibodies to HCV. This was not a significant finding and no statistical methods, e.g. Chi square test etc. could be applied. Conclusion: Hepatitis C virus is not significant to the causation of LP in India.

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is thought to be an immunologically mediated disorder. In LP lesions, there is infiltration in the dermis of T cells, both CD4+ and CD8+, while CD8+ T cells infiltrate the epidermis. The CD8+ cytotoxic T cells recognize an unknown antigen associated with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I on lesional keratinocytes and lyse them.[1],[2] A genetic susceptibility to idiopathic LP has been proposed. A familial incidence of 10.7% was quoted in one study.[3]

An epidemiological association of LP with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been recorded, especially in patients from Italy, where immunogenetic factors such as HLA-DR6 allele may account for geographical differences with regard to HCV infections and LP, and from certain parts of France, Italy, Spain, Japan and Pakistan.[4],[5] Some workers have isolated HCV RNA from lesional skin in patients with LP and chronic HCV infection[6],[7] and an HCV related product has been postulated as a possible antigen in LP. However, patients from northern Europe (including the UK), USA and Nepal have shown no association between LP and HCV infection.[8],[9],[10],[11] We conducted this study to determine whether HCV has a causal relationship with LP in Indian patients.

Methods

This study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology and Leprology of the School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata, from patients attending our hospital. The hospital caters to many patients from the eastern parts of India, and from Nepal and Bangladesh. Patients clinically diagnosed as LP between May 2004 and May 2005 were biopsied. All biopsy proven cases of LP were screened for HIV-1 and 2 because HIV infection may interfere with interpretation of HCV seropositivity. However, none were detected seropositive. The HIV-seronegative patients were tested for antibody to HCV by the reagent kit, SP-NANBASE C-96 3.0, developed by the General Biologicals Corporation, Taiwan ROC which adopts the second antibody "sandwich principle" as the basis for the assay to detect antibodies to HCV. This third generation anti-HCV diagnostic kit features structural and non-structural antigens specific for HCV.

The results were analyzed and compared with those of 150 HIV-seronegative controls selected from the out-patient department not suffering from LP and who were ready to participate in the study. These controls were more or less matched for age and sex [Table - 1].

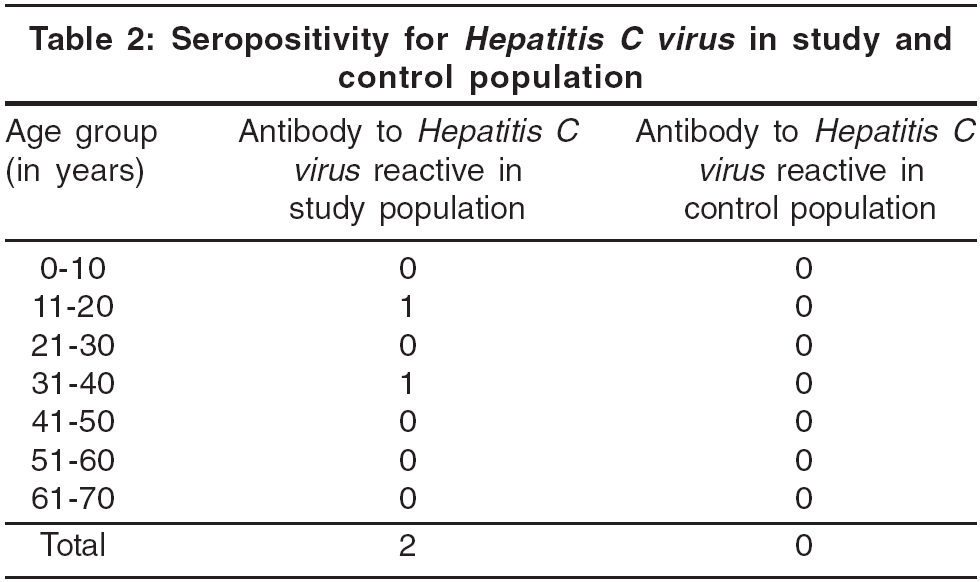

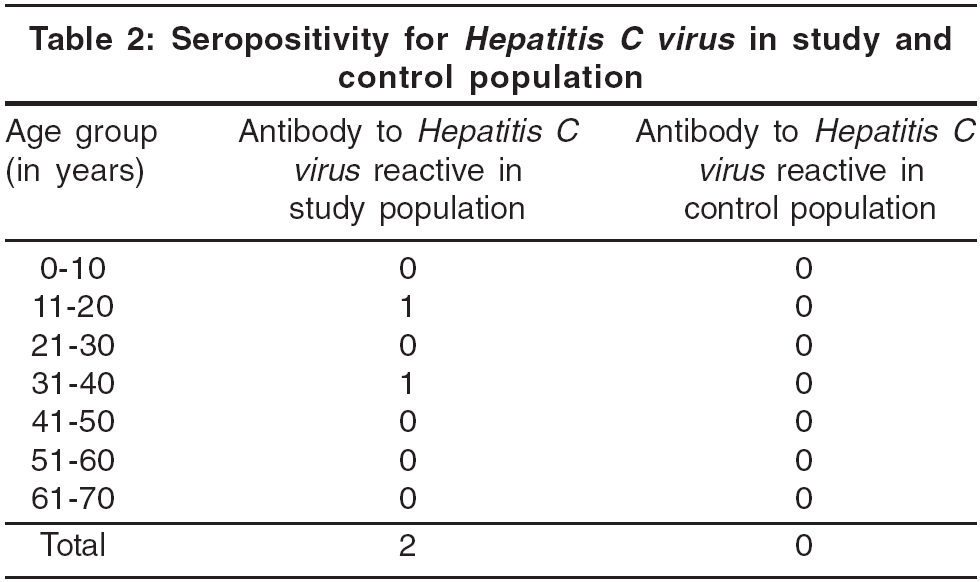

There were 104 patients studied [Table - 1], 43 (41.3%) males and 61 (58.7%) females. The male to female ratio was 1:1.41. The maximum number of patients (26 %) was in the 31-40 years age group. Two patients, both male, aged 18 years and 40 years were reactive to antibody to HCV, while all 150 age and sex matched controls were HIV-1 and -2 negative and also negative for antibody to HCV [Table - 2]. Two was too insignificant a number to apply any statistical methods, e.g. Chi square test or Fisher′s exact test etc.

Discussion

HCV infection has been proposed as a factor in the pathogenesis of LP. Depending on the background rate of HCV infection in the region, 4% to 38% of LP patients may have co-existing HCV infection.[12] In Northern Japan, where the seroprevalence of HCV infection is 8%, 60% of patients with oral LP had HCV infection.[12] One group had reported that 5% of all HCV infected patients have LP.[1] An epidemiological association of LP with HCV infection has been recorded in patients from various parts of the world and HCV RNA has been isolated from lesional skin in patients with LP and chronic HCV infection.[2],[10] Thus, an HCV related product has been postulated as a possible antigen in LP. It has been suggested that the observed geographical differences with regard to HCV infection and LP could be related to immunogenetic factors, such as the HLA-DR 6 allele, which is significantly expressed in Italian patients with oral LP and HCV infection.[4] However, no association between LP and HCV infection has been noted in patients from Northern Europe (including the UK), USA and Nepal.[11],[12],[13],[14]

We tested 104 patients of biopsy proven LP who were HIV-seronegative for antibody to HCV. Only two patients suffering from generalized LP of more than 3 months′ duration were anti-HCV antibody positive. The background rate of seroprevalence of HCV as per unpublished data of our virology department is 0.8%. All 150 controls of comparative age and sex groups tested negative for anti-HCV antibody.

We did not find any significant association between LP and HCV. In fact, the number of HCV positive patients was so low that we could not apply any statistical methods. Our results are comparable with other Indian studies[14],[15],[16] where only 2.66% cases were positive for the HCV antibody, which is almost parallel to the prevalence of HCV in the general population in India (1.5 to 2.2%).[3] However, while studies conducted in New Delhi have failed to demonstrate statistically significant association between HCV and LP,[17] studies conducted in Hyderabad and Bangalore have shown a significant association.[4],[5] Whether the geographical variation of Hep C seropositivity prevalence among LP patients may be attributed to genetic factors remains to be studied.

All the previously done studies including the present study suffer from the shortcoming of inadequate sample size. Future studies should be large enough to take into account this requirement and settle this issue.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution by Dr Sreema Adhikari, Virology Department, for most of the tests of the virology portion of this study and by Shri Tapan Kumar Kar, Medical Technologist, Virology Department, School of Tropical Medicine, for his technical assistance in anti-HCV tests.

| 1. |

Fayyazi A, Schweyer S, Soruri A, Duong LQ, Radzun HJ, Peters J, et al . T lymphocytes and altered keratinocytes express interferon-γ and interleukin 6 in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res 1999;291:485-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Sugarman PB, Satterwhite K, Bigby M. Autocytotoxic T-cell clones in lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:449-56.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Kofoed ML, Lange Wantzin GL. Familial lichen planus-more frequent than previously suggested? J Am Acad Dermatol 1985;13:50-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Carrozzo M, Francia Di Celle P, Gandolfo S, Carbone M, Conrotto D, Fasano ME, et al . Increased frequency of HLA-DR6 allele in Italian patients with hepatitis C virus -associated oral lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 2001;4:803-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Mahboob A, Haroon TS, Iqbal Z, Iqbal F, Butt AK. Frequency of anti-HCV antibodies in patients with lichen planus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2003;13:248-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Lazaro P, Olalquiaga J, Bartolome J, Ortiz-Movilla N, Rodriguez-Inigo E, Pardo M, et al . Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA and core protein in keratinocytes from patients with cutaneous lichen planus and chronic hepatitis C. J Invest Dermatol 2002;119:798-803.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Kurokawa M, Hidaka T, Sasaki H, Nishikata I, Morishita K, Setoyama M. Analysis of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in the lesions of lichen planus in patients with chronic hepatitis C detection of anti-genoic-as well as genomic-strand HCV RNAs in lichen planus lesions. J Dermatol Sci 2003;32:65-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Chuang TY, Stitle L, Brashear R, Lewis C. Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus. A case-control study of 340 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:787-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Tucker SC, Coulson IH. Lichen Planus is not associated with hepatitis C virus infection in patients from north west England. Acta Derm Venereol 1999;79:378-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Roy KM, Dickson EM, Staines KS, Bagg J. Hepatitis C virus and oral lichen planus/lichenoid reactions: lack of evidence for an association. Clin Lab 2000;46:251-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Garg VK, Karki BM, Agrawal S, Agarwalla A, Gupta R. A study from Nepal showing no correlation between lichen planus and hepatitis B and C viruses. J Dermatol 2002;29:411-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Grekin RC, Samlaska CP, Vin-Christian K. Andrews Diseases of the skin. In : Richard B. Odom, William D James, Timothy G Berger. Lichen Planus and Related conditions. 9th ed. WB Saunders Co: Philadelphia; 2000. p. 271.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Lazaro P, Olalquiaga J, Bartolome J, Ortiz-Movilla N, Rodriguez-Inigo E, Pardo M, et al . Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA and core protein in keratinocytes from patients with cutaneous lichen planus and chronic hepatitis C. J Invest Dermatol 2002;119:798-803.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Narayan S, Sharma RC, Sinha BK, Khanna V. Relationship between Lichen planus and Hepatitis C Virus . Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1998;64:281-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Prabhu S, Pavithran K, Sobhanadevi G. Lichen planus and hepatitis c virus (HCV) - Is there an association? A serological study of 65 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002;68:273-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Khaja MN, Madhavi C, Thippavazzula R, Nafeesa F, Habib AM, Habibullah CM, et al . High prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and genotype distribution among general population, blood donors and risk groups. Infect Genet Evol 2006;6:198-204. Epub 2005 Jun 28.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Irshad M, Achary SK, Joshi YK. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibodies in the general population and in selected groups of patients in Delhi. Indian J Med Res 1995;102:162-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,155

PDF downloads

2,418