Translate this page into:

Nodular melanoma on lip with retrograde in-transit metastases on face

Corresponding author: Dr. Krishnendu Mondal, Fularhat, P.O. and P.S. Sonarpur, District-South 24 Parganas., Kolkata - 700 150, West Bengal, India. kaminakriss@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Mondal K, Mandal R. Nodular melanoma on lip with retrograde in-transit metastases on face. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:687-9.

Sir,

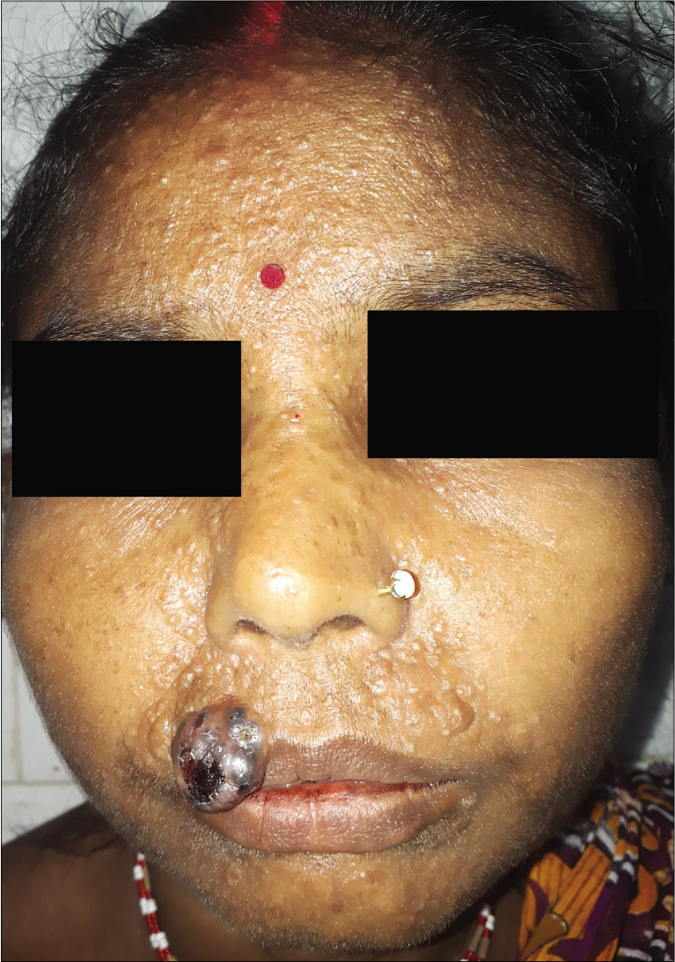

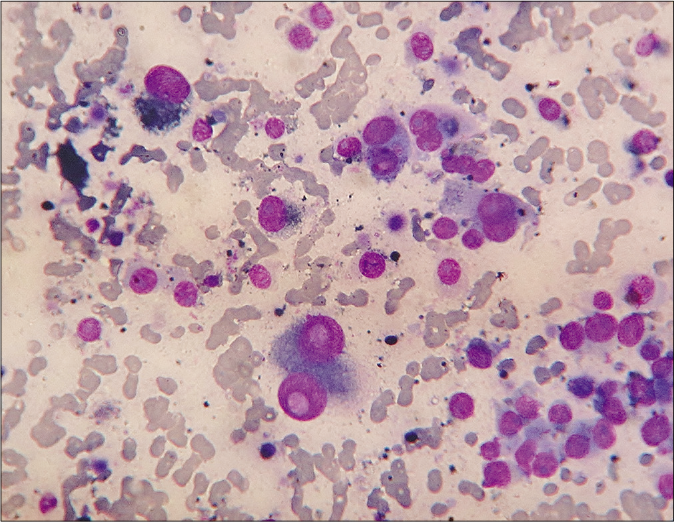

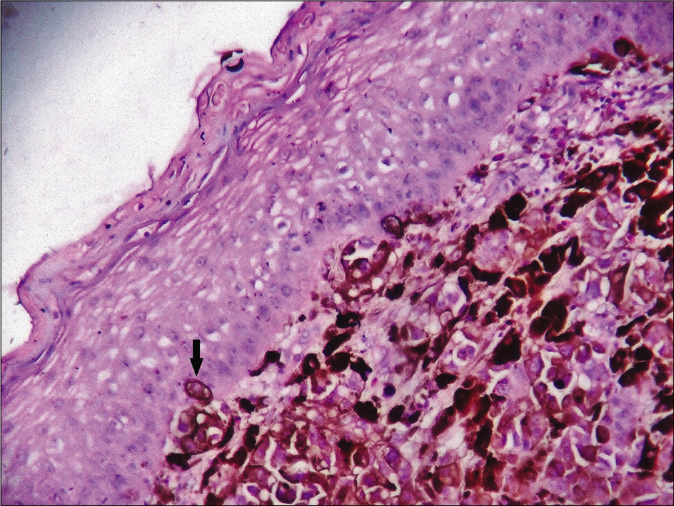

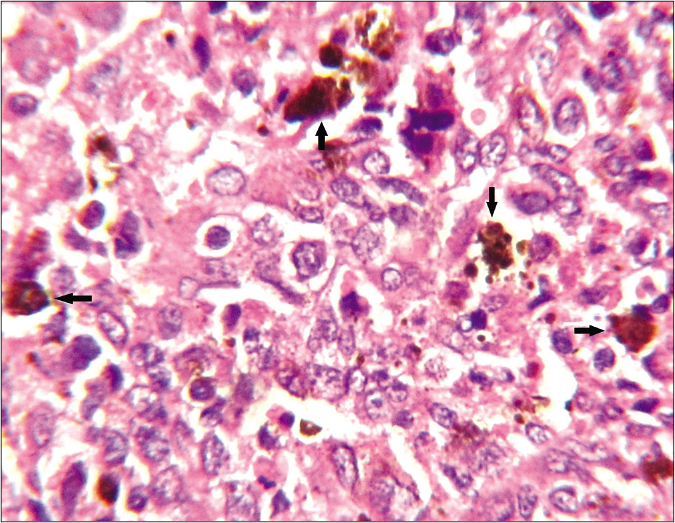

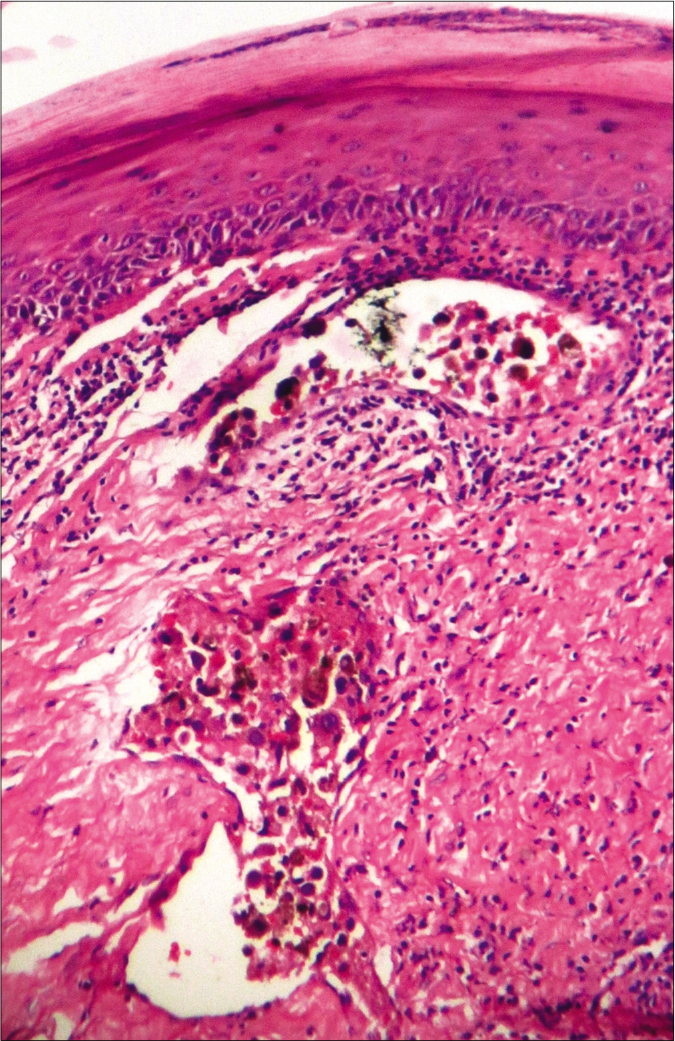

A 45-year-old woman presented with an ulcerated 4 × 3.5 cm nodule over the right half of upper lip for two months. It featured variegated pigmentation. Besides, there were numerous skin-colored papules over the pre-maxillary portion of upper lip, cheeks, nose and central forehead [Figure 1] for the past five weeks. Fine-needle aspiration cytology was performed from the lip mass. Multiple facial papules were sampled by slit skin preparation. Microscopically, all lesions expressed cell-rich aspirates, predominated by singly isolated large tumor cells. It featured eccentric round-shaped homogeneously hyperchromatic nuclei, marked anisokaryosis, prominent macronucleoli with occasional binucleation, multinucleation and intranuclear cytoplasmic pseudoinclusions. Their cytoplasm contained dusty melanin granules. The background contained extracellular pigment debris and melanophages [Figure 2]. Therefore, the diagnosis was a malignant melanoma with multiple facial satellitosis and in-transit metastases. However, most of these lesions from in-transit metastases were located in a reverse direction to conventional lymphatic flow. The tumor was excised with 2 cm resection margin, followed by autologous skin grafting. Histologically, the epidermis appeared thinned-out and focally denuded. Dermis was occupied by multiple small nests of melanoma cells, forming into an expansile nodule with expanding borders. Heavily pigmented melanocytes were sprinkled in variable proportions within the tumor [Figure 3]. The tumor cells appeared epithelioid in shape with abundant pale to clear or sometimes intensely pigmented cytoplasm. Nuclear chromatin seemed vesicular and clear with often prominent nucleoli [Figure 4]. Its Breslow depth was measured at 2.5 cm. Mitotic count approximated to 6/mm2. Confirmatory histopathology of the papules representing in-transit metastases revealed intralymphatic dissemination of the malignant melanocytes [Figure 5]. Submandibular sentinel lymph node biopsy was positive for metastatic deposits. On complete lymph node dissection, two more nodes expressed metastatic involvement. Positron emission tomography scan did not reveal any distant metastases from the tumor. It was ultimately categorized into T4bN3cM0 (Stage III D). The patient was systemically treated with interferon alfa-2b. Topical imiquimod was prescribed for her facial lesions. Still, she developed distant metastases at brain, lungs and mediastinal lymph nodes as isolated on positron emission tomography scan at six months during follow-up. Ultimately, she succumbed to the disease.

- Nodular melanoma on the right side of upper lip with numerous papules of satellitosis and in-transit metastases bilaterally on upper lip, nose, medial portion of both cheeks and central forehead

- Cytologically, dispersed polyhedral melanoma cells with one-or-two eccentric rounded nuclei, gross anisokaryosis, prominent nucleoli, intranuclear cytoplasmic pseudoinclusions and intracellular as well as background extracellular melanin granules (Leishman-Giemsa, ×400)

- Histologically thinned-out epidermis with the dermis occupied by nests of melanoma cells. Note the singly infiltrating tumor cells (arrow) within the epidermis (hematoxylin-eosin, ×400)

- Histologically, in areas with sporadic presence of heavily-pigmented melanocytes (arrows), the tumor cells were better elicited as epithelioid in shape having large vesicular nuclei, often prominent nucleoli and abundant pale or clear cytoplasm (haematoxylin-eosin stain, ×1000)

- In-transit metastasis, featuring malignant melanocytes within dermal lymphatics (hematoxylin-eosin, ×100)

The American Joint Committee on Cancer assigns the microsatellites, satellites and in-transit metastases from melanoma into the N “c” subcategory. In their presence, the tumor-involved regional nodes are classified as N1c, N2c and N3c, when either 0, 1 or ≥2 regional nodes are, respectively, involved. In-transit metastases occur as cutaneous or subcutaneous lymphatic dissemination before the regional nodal basin, which is located more than 2 cm away from the primary tumor. Around 5–10% primary melanoma patients develop concurrent in-transit deposits. After treatment, also 4–11% of patients relapse with such lesions as locoregional recurrence.1 In-transit spread is more prevalent for melanoma located on the extremities. Head-neck region, trunk and genitalia are only exceptionally involved.2 These lesions carry an unfavorable prognostic factor, associated with frequent distant spread.1,2 The currently described patient developed these deposits soon after the origin of primary tumor at her upper lip. The intransit lesions prevailed rearwards and bilateral symmetrically up to forehead, besides appearing en route of the draining submandibular nodes. Despite treatment, she quickly progressed toward life-threatening multiorgan metastatic disease.

The submandibular group of lymph nodes receives its afferents from the upper lip, lateral portion of lower lip, nose, medial cheek, glabella and centromedian forehead. Across the sagittal line, their corresponding lymphatics from either side ramify with each other.3 Similarly, in the present case, the submandibular basin served as the sentinel node for the melanoma on upper lip. The patient was also suffering from innumerable in-transit metastatic deposits over her upper lip, cheek, nose and forehead, coinciding with the afferent and converse lymphatic distribution of bilateral submandibular nodes. Such retrograde lymphatic spread of malignancy results from downstream increase in the intralymphatic pressure caused by lymphatic obstruction. It commonly occurs with malignant invasion or by any extrinsic mechanical hindrance likely to be associated here with mastication or facial arterial pulsation.4 Earlier literature recorded retrograde lymphatic dissemination of carcinoma from esophagus, lungs, pleura, mediastinum, heart, pericardium, spleen, retroperitoneum and genitourinary organs.5 However, similar evidence for a melanoma on lip and retrograde dissemination along the collateral lymphatics has not yet been described. In the discussed context, a downstream lymphatic obstruction leading to retrograde spread of melanoma cells well into the ramifying collaterals best explains the pathogenesis.

Tumors such as basal cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, dermatofibroma, certain skin appendageal tumors and squamous cell carcinoma may also present as pigmented skin nodule.6 However, unlike others, melanoma is a highly recurrent tumor and requires radical excision with 2 cm rim of uninvolved skin. In addition, sentinel lymph node assessment is also necessary for its management.2 In this purpose, a pre-operative diagnosis is mandatory which is best achieved through fine-needle aspiration technique.7 Likewise, the lip mass discussed here and its in-transit deposits were easily diagnosed on cytology. Successive histopathology confirmed the diagnosis. The treatment protocol was then modified accordingly.

Common immunohistochemical markers of melanoma include S-100, Human Melanoma Black (HMB-45), Melan A and melanoma-associated antigen 1 (MAGE-1).6 However, the discussed tumor expressed characteristic cytomorphology of melanoma. Biopsy from the in-transit metastatic lesions established the lymphatic dissemination of malignant melanocytes. A further positron emission tomography scan affirmed the tumor at Stage IIID (T4bN3cM0). Anatomically, the upper lip belongs to the area, namely, “dangerous triangle of face.” Venous drainage from this triangle communicates with intracranial cavernous sinus.8 Involvement of an identical pathogenic pathway could have led to early cerebral metastases for the discussed patient as well. Moreover, the proximity of in-transit lesions to both her eyes also carried significant risk of ocular and orbital invasion.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American joint committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual In: CA Cancer J Clin. Vol 67. 2017. p. :472-92.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Management of in-transit malignant melanoma In: Duc GH, ed. Melanoma: From Early Detection to Treatment. London: Intech Open; 2013. p. :255-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation and localization of lymphatic drainage and sentinel lymph nodes in patients with head and neck melanomas by hybrid SPECT/CT lymphoscintigraphic imaging. J Nucl Med Technol. 2007;35:10-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retrograde lymphatic spread of esophageal cancer: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1139.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A clinicopathologic study of malignant melanoma based on cytomorphology. Indian J Cancer. 2016;53:199-203.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anatomy of the facial danger zones: Maximizing safety during soft-tissue filler injections. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:50e-8e.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]