Translate this page into:

Non-cultured epidermal suspension in vitiligo: From laboratory to clinic

2 Department of Dermatology, Ibn Sina University Hospital, Mohammed V Souissi University, Rabat, Morocco

Correspondence Address:

Yvon Gauthier

52 rue Pasteur 33110, le Bouscat

France

| How to cite this article: Gauthier Y, Benzekri L. Non-cultured epidermal suspension in vitiligo: From laboratory to clinic. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:59-63 |

Abstract

Background: Medical treatments are ineffective in many patients and surgical methods have therefore been developed. Objective: A review of autologous non-cultured melanocyte grafting techniques is proposed to obtain a successful repigmentation of vitiligo macules. Methods: Initially in 1992, we had developed a simplified grafting method which was carried out in the following two steps: production of blisters on the depigmented lesions by freezing with liquid nitrogen and injection in each blister of a non-cultured suspension of epidermal cells. The cellular suspension was obtained from samples of skin of the hair scalp after trypsinization. This very simple technique could be used at the dermatologist's clinic. Since 1998 (Olsson MJ, Juhlin L), quite comparable but improved and more sophisticated techniques have been proposed for the surgical treatment of vitiligo. These techniques require a laboratory set up to perform the melanocyte transplantation. The donor zone was usually taken on the gluteal region. The time of trypsinization was reduced to 60 minutes at 37C and the centrifuged cellular suspension added with hyaluronic acid (Van Geel) was directly applied on a dermabraded or laser abraded vitiligo lesions. Results: Whatever the technique chosen, repigmentation was evident within 25 to 30 days. Coalescence of the pigmented areas was spontaneously observed or obtained after UVB radiation. It is obvious that the complete repigmentation occurred more rapidly with the recent techniques compared with the initial method, but the efficiency was quite similar. Conclusion: The use of non-cultured epidermal suspension appears to be an effective, safe, and simple method for treating patients with achromic areas lacking melanocytes.Introduction

Vitiligo is the most common depigmenting dermatosis that affects approximately 0.5 to 1% of the general population regardless of race and sex. [1] Treatment of vitiligo by transplantation of autologous pigmented skin grafts or blister roofs has been carried out for about 45 years. Punch grafts can give rise to cobblestone-like scars, but this has been avoided by using blister roofs. The blisters have been produced on normal skin by suction and transplanted to white areas.

The first non-cultured epidermal cellular grafting was performed in experimental conditions on piebald guinea pig skin by Billingham and Medawar. [2] Having a good experience of this technique on guinea pig skin, we introduced in 1992 the use of non-cultured epidermal cellular grafting for the treatment of stable vitiligo. [3],[4] A donor sample was obtained from the hair scalp by superficial shaving and treated with 0.25% trypsin solution during 18 hours. The suspension was inoculated at the recipient area into blisters raised with liquid nitrogen. Several years later in 1998, Olsson and Juhlin reported a comparable but improved technique. [5] The donor skin was taken from the gluteal region, the time for trypsinization was reduced to 60 minutes, and the cellular suspension was directly applied onto a dermabraded vitiligo lesion. In 2001, Van Geel et al. introduced the use of hyaluronic acid as biodegradable cell carrier to increase the viscosity of the suspension. [6],[7]

In this review, we present the overview of the initial technique (preparation of the basal cell layer suspension, transplantation timing), its recent modifications, and the advantages of this method compared with other melanocyte transplantation modalities.

Preparation of the basal cell layer suspension

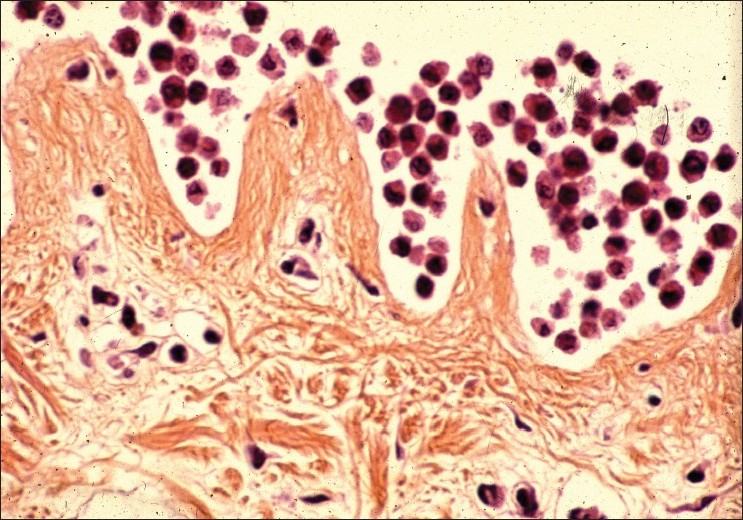

The original technique for dissociating human skin samples involved treatment at 4°C with a 0.25% trypsin solution to shear off remaining dermis and to loosen cell-to-cell adhesion, followed by vigorous mechanical dissociation in plasma of the patient. Treatment at high trypsin concentration and 37°C followed by vigorous agitation dissociates the epidermis almost completely. However, the yield of intact cells is lower and the cells exhibit numerous vacuoles throughout the cytoplasm. In contrast, in our method, mild trypsinization of the epidermis in the presence or not of EDTA at low enzyme concentration and 4°C produces an incomplete dissociation [Figure - 1], but nevertheless gives a higher yield of single viable cells. The beneficial effect of this treatment can be explained by the fact that endocytotic uptake of trypsin is negligible at 4°C, whereas trypsin taken up at 37°C persists in the cells for up to 48 hours. [8] Mechanical agitation of the skin samples provokes a complete detachment of keratinocytes and melanocytes remaining in the basal layers [Figure - 2].

|

| Figure 1: Aspect of the epidermal basal layers (keratinocytes + melanocytes) after trypsinization at 4°C during 18 hours HES staining (×100) |

|

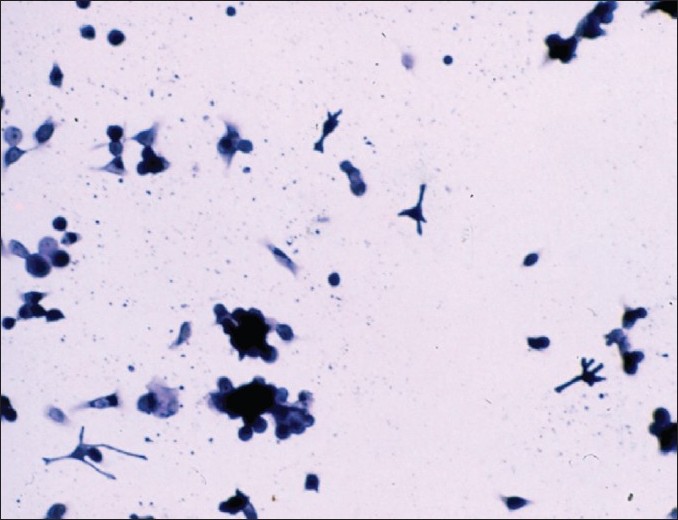

| Figure 2: Epidermal cellular suspension (keratinocytes + melanocytes) after manual agitation Giemsa staining (×100) |

Methods

Transplantation of basal cell layer suspension was carried out in the following two steps:

The first day

Donor site

0A shave biopsy specimen (4 up to 10 cm 2 ) was taken under local anesthesia using a hand dermatome from the patient′s normally pigmented occipital area of the hair scalp. The skin sample was immediately put in a test tube containing 0.25% trypsin solution and placed overnight at 4°C.

Recipient site

The recipient areas were cleaned with Hexamidine and outlined with a surgical marking pen. To induce blisters on the achromic areas, freezing with liquid nitrogen spray was performed during 10 to 20 seconds inside round circles previously drawn on the skin.

20 cc of blood was taken from the patient in order to use plasma as vehicle for the cell suspension on the second day.

The second day

Preparation of cell suspension

After incubation, the trypsin solution was removed and about 2 ml of plasma was added in the petri dish to discontinue the trypsin reaction without the help of specific trypsin inhibitor. The superficial and mid epidermis was removed from the basal epidermis and the superficial dermis with fine forceps and the lower part of the epidermis was transferred to a test tube containing about 4 cc of plasma. This tube was strongly and horizontally shaken for 3 minutes to obtain the complete detachment of the basal cells. The dermal pieces were then discarded. The cell suspension obtained in plasma thus contained cells from the basal cell layer including keratinocytes and melanocytes [Figure - 2]. In the initial and simple technique, we have not used a laminar flow bench for the procedure of cell separation and the epidermis was not vortex mixed and the cell suspension was not centrifuged.

Melanocyte transplantation

The cell suspension was aspirated with insulin syringes and injected into the blisters raised by freezing on the recipient site. The exact number of grafted melanocytes is very difficult to assess because the suspension consists of a heterogeneous population of cells (melanocytes and keratinocytes). However, an approximate estimation has been done and 4 to 5 melanocytes are present in a drop of suspension. Immediately, transplanted areas were covered with gauzes moistened with plasma, held in place with Tegaderm transparent dressing and bandages. In all cases, the patient should rest horizontally immobile for at least 30 minutes after the procedure has been completed. The patient is informed that the first 48 hours are the most critical for the outcome and that it is important to restrict the physical activities. The dressing is usually changed every 48 hours during two weeks.

Follow-up evaluation

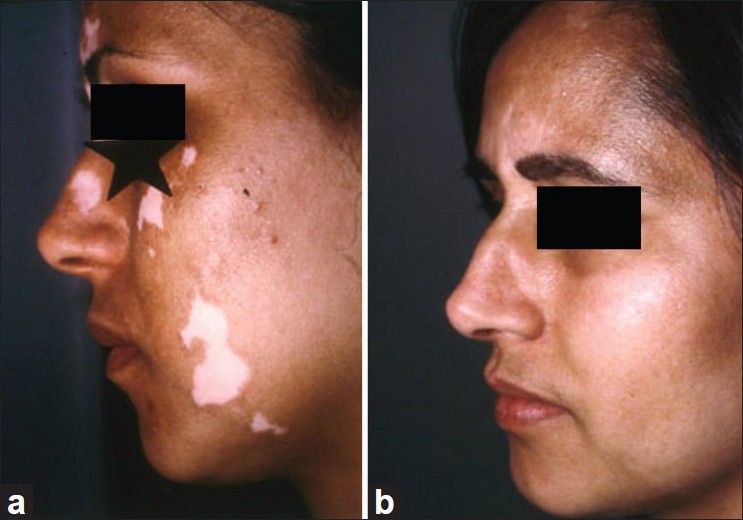

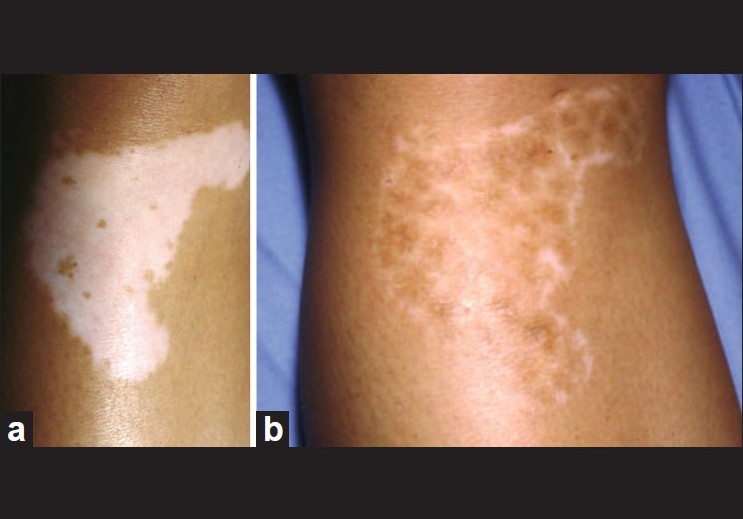

During the first few weeks after the crust detachment, the transplanted area remains erythematous. The repigmentation usually starts on Caucasoid skin one month after the transplantation. The patients are advised to expose themselves to midday sunlight for a few minutes, 2 times a week for about 2 months. In some cases, narrowband UVB (NB UVB) should be started 3 weeks following grafting for a period of 3 months. After 4 months, there usually was a good coalescence between the repigmented areas [Figure - 3]. Sometimes, a 1-2 mm depigmented halo persists around the transplanted area. The pathogenesis of this phenomenon is unclear. It is possible that the injection of the epidermal suspension was done too far from the edge. However, this is seen more often in patients with generalized vitiligo than in those with segmental vitiligo, and other trials of melanocyte transplantations usually failed [Figure - 4]. On this basis, we hypothesize that this anomaly was probably related to local autoimmunity. It is obvious that patients with stable forms of vitiligo, namely segmental and focal vitiligo, benefit most from this surgical treatment, since they generally retain full pigmentation and have minimal chances of developing new lesions in the future.

|

| Figure 3: (a) Segmental vitiligo of the face before melanocyte transplantation, (b) Repigmentation 6 months after melanocyte transplantation (good cosmetic result) |

|

| Figure 4: (a) Non-segmental vitiligo of the knee before melanocyte transplantation, (b) Incomplete repigmentation 6 months after melanocyte transplantation |

Modifications of the initial technique

The initial and very simple technique was improved by Olsson and Juhlin [5] by adding a melanocyte culture medium for the stimulation of melanocyte growth. A donor area of about 1/10 th of the recipient area was chosen on the lateral side of gluteal region. The recipient area was abraded down to dermoepidermal junction with a high-speed dermabrader fitted with diamond fraise wheel. The centrifuged cell suspension was applied to the denuded areas and spread with the tip of a syringe or a pipette. Further on, the technique was modified in 2001 by Van Geel et al.[6] by increasing the adherence of cells to the grafted surface, with hyaluronic acid added to the cell suspension. [9],[10]

Kaufmann et al.[11] and Chen et al.[12] have shown that deepithelialization of the recipient site with the help of Er:YAG (erbium:yttrium-aluminium-garnet) or short-pulse carbon dioxide laser in transplantation of melanocytes can give similar results as with dermabrasion. Guerra et al.[13] have successfully used programmed diathermosurgery to deepithelialize the recipient areas. Ultrasonic abrasion has also been successfully used for transplanting melanocytes in vitiligo. [14]

All these improved techniques were performed in an operation theater and requires a properly equipped laboratory and a personnel specially trained in preparation and handling of live cells.

For only smaller vitiligo patches, autologous, non-cultured, non-trypsinized melanocyte and keratinocyte grafting have been proposed by Kachhawa and Kaila. [15] Recently, Goh et al. have simplified the extraction of epidermal cells from donor skin using a simple inexpensive six-well plate, a microfilter, and only three reagents: trypsin, trypsin inhibitor (soybean), and phosphate buffered saline (PBS). [16]

Discussion

Non-cultured epidermal suspension is indicated mainly for segmental vitiligo and for stable non-segmental vitiligo that does not respond to medical treatment. For the assessment of stability, Parsad and Gupta [17] suggested as definition the absence of progression of the disease for the past one year. The results obtained with basal cell layer transplantation are as good as those seen after transplantation of cultured melanocytes. Pandya et al.[18] reported that an excellent response was seen in 52.17% cases with non-cultured epidermal suspension technique and in 50% with the melanocyte culture technique. Gupta et al.[19] have developed a scoring system with an original approach considering the extent of pigmentation, color match, and the complications of both the donor and the recipient area. A new analysis system for surface measurement of vitiligo lesions was proposed by Van Geel et al. [20] According to Olsson and Juhlin [21] and Van Geel et al., [22] a significant repigmentation was observed in 70% of patients. Best results were obtained by Mulekar [23],[24],[25] in segmental vitiligo (84%), whereas results in generalized vitiligo were inferior (56%). [26] During follow-up, 6.7% of patients with generalized vitiligo observed some loss of the achieved repigmentation. Certain areas such as the fingers and toes, palms and soles, lips, eyelids, nipples, and areolas are considered difficult to treat. But, according to Mulekar et al.[27] more than 50% of patients treated for difficult sites showed more than 65% repigmentation of the treated areas by non-cultured epidermal suspension.

In 20% of cases, an incomplete repigmentation occurs on nonsegmental vitiligo macules whatever the technique used. This defect is not depending on the technique but on the type of vitiligo. Olsson demonstrated that patients with extensive vitiligo more often showed incomplete repigmentation with any surgical modality. It was the case for the second patient [Figure - 4]a and b. After the treatment of approximately 200 patients, we have never observed hypopigmentation on the donor site located on the scalp. In our experience (approximately 20% of cases), imperfect color matching of the grafted area was caused either by hypopigmentation or by hyperpigmentation. Hypopigmentation can be explained by an insufficient concentration of grafted melanocytes or possibly by reactivation of the disease. In the opposite, hyperpigmentation may be related to overstimulation of melanocytes by growth factors or cytokines during the healing. To reduce hyperpigmentation, Gupta et al.[19] suggested that any form of postoperative radiation therapy should be stopped when sufficient color matching is achieved. Scars or keloid formations have never been reported at donor site like after skin transplant.

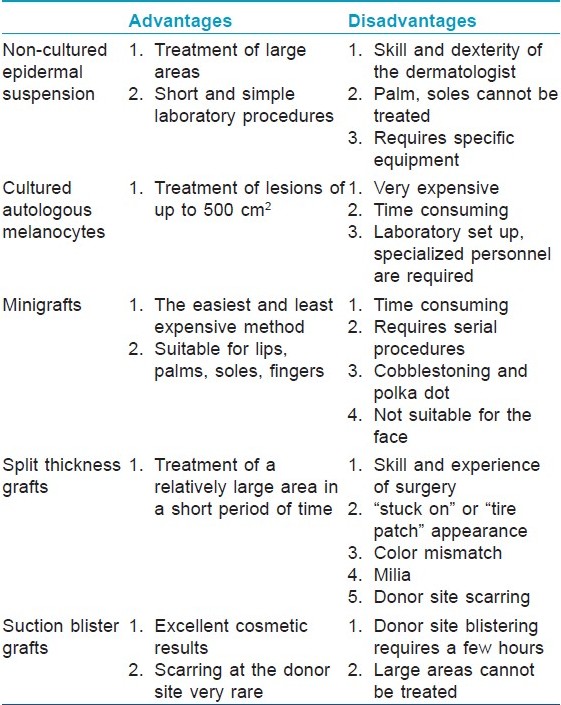

The advantage of this method over the cell culture method is that it is simple and do not require expensive culturing conditions and high-tech laboratories. Nevertheless, basal cell layer suspension method requires a dermatologist who is familiar with the separation of human skin after trypsinization. The potential advantage of techniques based on cell separation is to allow the treatment of larger lesions than techniques based on whole tissue such as minigrafts, suction blister grafts, except split thickness grafts which had many disadvantages [Table - 1].

Conclusion

The non-cultured epidermal suspension techniques are safe, effective, and simpler than the other methods involving cell culturing and requiring a laboratory set-up. Selection of patients is crucial for the success of the outcome.

| 1. |

Taieb A, Picardo M. The definition and assessment of vitiligo: A consensus report of the Vitiligo European Task Force. Pigment Cell Res 2007;20:27-35.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Billingham RE, Medawar PB. Pigment spread in mammalian skin: Serial propagation and immunity reaction. Heredity 1950;4:141-64.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Gauthier Y, Surleve-Bazeille JE. Autologous grafting with non cultured melanocytes: A simplified method for treatment of depigmented lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26:191-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Gauthier Y. Les techniques de greffe melanocytaire. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1995;122:627-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Olsson MJ, Juhlin L. Leucoderma treated by transplantation of a basal cell layer enriched suspension. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:644-8

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Van Geel N, Ongenae K, De Mil M, Naeyert JM. Modified technique of autologous non cultured epidermal cell transplantation for repigmenting vitiligo a pilot study. Dermatol Surg 2001;27:873-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Van Geel N, Ongenae K, De Mil M, Naeyaert JM. Double blind placebo-controlled study of autologous transplanted epidermal cell suspensions for repigmenting vitiligo. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:1203-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Vielkind U, Crawford BJ. Evaluation of different procedures for the dissociation of retinal pigmented epithelium into single viable cells. Pigm Cell Res 1988;1:419-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Back C, Dearman B, Li A. Non cultured keratinocyte-melanocyte cosuspension: Effect on reepithelialization and repigmentation: A randomized placebo-controlled study. J Burn Care Res 2009;30:408-16.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Xu AE, Wei XD, Cheng DQ, Zhou HF, Qian GP. Transplantation of autologous non cultured epidermal cell suspension in treatment of patients with stable vitiligo. Chin Med J (Engl) 2005;118:77-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Kaufmann R, Greiner D, Kippenberger S, Bernd A. Grafting of in vitro cultured melanocytes onto laser-ablated lesions in vitiligo. Acta Derm Venereol 1998;78:136-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Chen YF, Chang JS, Yang PH, Hung CH, Huang MH, Hu DN. Transplant of cultured autologous pure melanocyte after laser abrasion for the treatment of segmental vitiligo. J Dermatol 2000;27:434-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Guerra L, Capurro S, Melchi E, Primavera G, Bondanza S, Cancedda R. Treatment of « stable » vitiligo by timed surgery and transplantation of cultured epidermal autografts. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:1380-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Tsukamoto K, Osada A, Kitamura R. Approaches to repigmentation of vitiligo skin: New treatment with ultrasonic abrasion, seed-grafting and psoralen plus ultraviolet TA therapy. Pigm Cell Res 2002;15:331-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Kachhawa D, Kaila G Keratinocyte-melanocyte graft technique followed by PUVA therapy for stable vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:622-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Goh BK, Chua XM, Chong KL, De Mil M, Van Geel NA. Simplified Cellular grafting for treatment of Vitiligo and Piebaldism: The "6-Well Plate" technique. Dermatol Surg 2010;36:203-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Parsad D, Gupta S. Standard guidelines of care for vitiligo surgery. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:37-45.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Pandya V, Parmar KS, Shah BJ, Bilmora FE. Study of autologous melanocyte transfer in treatment of stable vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2005;71:71-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Gupta S, Honda S, Kumar B. A novel scoring system for evaluation of results of autologous transplantation in vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002;68:33-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Van Geel NA, Ongenae K, Vander Haeghen YM, Naeyaert JM. Autologous transplantation techniques for vitiligo: How to evaluate treatment outcome. Eur J Dermatol 2004;14:46-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Olsson MJ, Juhlin L. Long term follow-up study of leucoderma patients treated with transplants of autologous cultured melanocytes, ultrathin epidermal sheets and basal cell layer suspension. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:893-904.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Van Geel N, Ongenae K, Vander Haeghen Y, Vervaet C, Naeyaert JM. Subjective and objective evaluation of non-cultured epidermal cellular grafting for repigmenting vitiligo. Dermatology 2006;213:23-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Mulekar SV. Melanocyte-keratinocyte cell transplantation for stable vitiligo. Int J Dermatol 2003;42:132-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Mulekar SV. Long-term follow-up study of segmental and focal vitiligo treated by autologous, non-cultured melanocyte-keratinocyte cell transplantation. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:1211-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Mulekar SV, Al Eisa A, Delvi MB, Al Issa A, Al Saeed AH. Childhood vitiligo: A long term study of localized vitiligo treated by non-cultured cellular grafting. Pediatr Dermatol 2010;27:132-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Mulekar SV. Long term follow-up study of 142 patients with vitiligo vulgaris treated by autologous non cultured melanocyte-keratinocyte cell transplantation. Int J Dermatol 2005;44:841-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Mulekar SV, Al Issa A, Al Eisa A. Treatment of vitiligo on difficult-to-treat sites using autologous non cultured cellular grafting. Dermatol Surg 2009;35:66-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

10,604

PDF downloads

3,038