Translate this page into:

Patient-assisted teledermatology practice: What is it? When, where, and how it is applied?

Correspondence Address:

Garehatty Rudrappa Kanthraj

"Sri Mallikarjuna Nilaya", #Hig33 Group 1 Phase 2,Hootagally KHB Extension, Mysore - 570018, Karnataka

India

| How to cite this article: Kanthraj GR. Patient-assisted teledermatology practice: What is it? When, where, and how it is applied?. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2015;81:136-143 |

Abstract

Recent teledermatology practice has been focused on different models made possible by robust advances in information technology leading to consistent interaction between the patient and health care professionals. Patient-assisted teledermatology practice also called patient-enabled teledermatology or home based teledermatology is one such novel model. There is a lack of scientific literature and substantive reviews on patient-assisted teledermatology practice. The present article reviews several studies and surveys on patient-assisted teledermatology practice and outlines its advantages and barriers to clinical utility and analyses the potentiality of this concept. Incorporating patient-assisted teledermatology practice as a novel model in the revised classification of teledermatology practice is proposed. In patient-assisted teledermatology, the patient can upload his/her clinical images as a first contact with the dermatologist or an initial face-to-face examination can be followed by teledermatology consultations. The latter method is well suited to chronic diseases such as psoriasis, vitiligo, and leg ulcers, which may need frequent follow-up entailing significant costs and time, particularly in the elderly. Teledermatology may also be used by the treating dermatologist to seek expert opinion for difficult cases. Studies have demonstrated the importance and usability of the concept of patient-assisted teledermatology practice. Various teledermatology care models are available and the appropriate model should be chosen depending on whether the clinical situation is that of easily diagnosed cases ("spotters"), chronic cases or doubtful cases and difficult-to-manage cases.INTRODUCTION

Telemedicine is an exchange of information at a distance, whether that information is voice, an image, elements of a medical record or commands to a surgical robot. Teledermatology imparts dermatology care from a distance by using electronics, communications and information technology to transmit the information between the patient and dermatologist and vice versa. [1] Similar to radiology, dermatology is a visual specialty utilizing clinical and histopathological images for diagnosis, which make it an ideal choice for telemedicine practice. Moreover, the use of novel advances in teleapplications by clinical dermatologist have paved the way for rapid growth in teledermatology.

Among dermatologists, there is some confusion about terms like teledermatology, teledermatology tools, and teledermatology practice. [2] Teledermatology is a branch of dermatology that deals with the application of healthcare information technology for research and practice in dermatology care. Teledermatology tool is an information technology platform to transmit clinical data between health care professionals and patients and vice versa. Teledermatology practice is an adoption of teledermatology tools to deliver efficient dermatology care for a clinical environment by health care professionals [Figure - 1]. Teledermatology practice encompasses all tools that can be applied in a wide array of ways, either singly or in combination, based on the clinical setting. [3] Hybrid teledermatology comprises a coalescence of dermatology tools like store-and-forward technology and video conference in a clinical ambience. [4] Dermatological treatment to combat pigmented skin lesions can be significantly improved by using a combination of teledermatology tools like store-and-forward technology or mobile teledermatology and teledermoscopy. [5]

|

| Figure 1: A proposed classification of teledermatology practice and various teledermatology tools used for practice |

The type of e-health care interaction between clinical dermatologists and patients will differ based on the dermatological condition. Thus, a regular or conventional teledermatology practice involves a general practitioner or nurse serving as liaison to deliver data to the expert, receive the expert′s opinion and then advise the recommended treatment to ensure efficient dermatology care for a remote or rural health care setting. [6] However, in patient-assisted teledermatology practice, the patient plays a pivotal role and he/she both sends the data and receives advice directly from a dermatologist using electronics and information technology[Figure - 1]. [7] In this view, patient-assisted teledermatology practice can be referred to as patient centered teledermatology or home-based teledermatology, and patients play a dual role of information providers as well as receivers.

In patient-assisted teledermatology practice, primarily, the patient seeks medical assistance directly from a dermatologist. In its secondary variant, the dermatologist conducts an initial face-to-face examination for a chronic skin condition like psoriasis or leg ulcer, assesses the severity through clinical investigations like skin biopsy, and subsequently advises the treatment and scrutinizes the condition by teledermatology to deliver further follow-up care. [8],[9]

Classification of teledermatology practice: Revisited

Due to the great strides in health care information technology, a systematic classification that validates the utility of teledermatology practice is necessary. The classification should provide new insights regarding the progress, benefits, pitfalls, planning, and implementation of teledermatology practice by health care organizations thus helping to deliver efficient care to the patient community.

Previous reviews explored the classifications of teledermatology practice, which encompasses a constellation of teledermatology tools. [2],[3],[6] However, robust advances in teledermatology tools and novel teledermatology approaches adopted by health care professionals have resulted in the requirement for a newer classification. Mobile teledermatology, which uses cellular phones for dermatology care, is a variant of store and forward technology and video conference and it differs in the additional requirement for net connectivity technology. Further, some studies have reported the advent of teledermatology in pediatric [10],[11] and geriatric [12] dermatology. Division of various types of teledermatology practice helps to observe the diagnostic accuracy, patient-dermatologist satisfaction, economic analysis with respect to each type of teledermatology practice. However, previously proposed classifications of teledermatology practice, [2],[3] did not include patient-assisted teledermatology practice. Tech savviness among the younger generation and rapid growth of electronic gadgets across the globe makes patient-assisted teledermatology practice an important area of teledermatology.

In accordance with the Wooten and Edey [6] review, teledermatology tools are divided into (i) store-and-forward, comprising the transmission of static images, and (ii) videoconference, comprising the transmission of moving images. Later hybrid teledermatology tool, [4],[13] a combination of store-and-forward and video conference, and mobile teledermatology, [14] -comprising the transmission of images using cellular phones were included in the classification. However, with the perception of the differences between teledermatology tools and teledermatology practice, Kanthraj in 2009 proposed a classification of teledermatology practice based firstly, on the diverse tools employed such as store-and-forward technology and video conference, hybrid and mobile teledermatology and secondly, on the health care professional involved in teledermatology. [3] This classification describes the following types of teledermatology practice: (i) General practitioner or nurse-assisted teledermatology practice (ii) specialist-to-specialist (tertiary) teledermatology practice for complicated cases, and (c) pediatric and geriatric teledermatology practice to deliver sub specialty care in dermatology. [3]

A recent longitudinal study analyzed the diagnostic accuracy of various teledermatology tools and recommended that plans for implementing a teledermatology practice could be based on this classification. [15] The dermatology conditions that were classified for teledermatology practice as a) Regular teledermatology practice b) tertiary teledermatology practice and c) subspecialty (pediatric and geriatric) teledermatology practice. [15] The advantage is assessment of feasibility and diagnostic accuracy with respect to each subdivision of teledermatology practice could be audited and analyzed for implementation. The diagnostic accuracy for general teledermatology practice using store and forward, video conference and mobile teledermatology tools is 73%, 70% and 70% respectively. The diagnostic accuracy for subspecialty teledermatology for pediatric and geriatric is 65% and 88% respectively 15 . Several studies have demonstrated acceptable diagnostic accuracy for various teledermatology tools. [16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24] Thus, the proposed revised classification clearly delineates teledermatology tools from teledermatology practice and includes patient-assisted teledermatology practice in it [Figure - 1]. In this scenario, the revised proposed classification of teledermatology practice can be broadly divided as:

- Regular teledermatology practice: Interaction between dermatologists and general practitioners who are at a distance from each other, for the delivery of speciality care for common dermatological problems. The general practitioner may even be in a remote geographic region. A regular teledermatology practice may utilize any of the teledermatology tools such as store and forward, videoconference, mobile tool, and hybrid tool

- Tertiary teledermatology practice: Knowledge transfer among dermatologists to combat difficult to manage cases through online discussion forum

- Sub-specialty teledermatology practice: Information flow among dermatologists specialized in pediatric and geriatric dermatology care, popularly use store and forward tool, and

- Patient-assisted teledermatology practice: Patient-dermatologist interaction for common skin-related diseases or follow-up care for chronic dermatological conditions. Store and forward [25] and mobile technology [26] are widely applied tools in patient-assisted teledermatology practice.

Indications and applications of patient-assisted teledermatology practice

The success of teledermatology practice in a health care setting, depends on the technical utility of the teledermatology tool and factors like patient and physician willingness and satisfaction. Various clinical studies have demonstrated the feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of teledermatology tools. [16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24] Further, substantial clinical surveys elicited valid information regarding patient perceptions, willingness, and satisfaction from both patient and dermatologist perspectives for teledermatology practice. [7],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31] Various studies [16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24] and surveys [27],[28],[29],[30],[32] on regular, tertiary, sub-specialty teledermatology practice and patient-assisted teledermatology practice [7],[31] have demonstrated their feasibility. A recent survey revealed positive perceptions with patient-assisted teledermatology practice. [31] Some of these studies, suggest that patient-assisted teledermatology practice may lead to satisfaction because of the rapid positive response from the teledermatologist. [7],[30],[31] However, absence of personal interaction between patient and dermatologist may hamper the clinical utility of this modality.

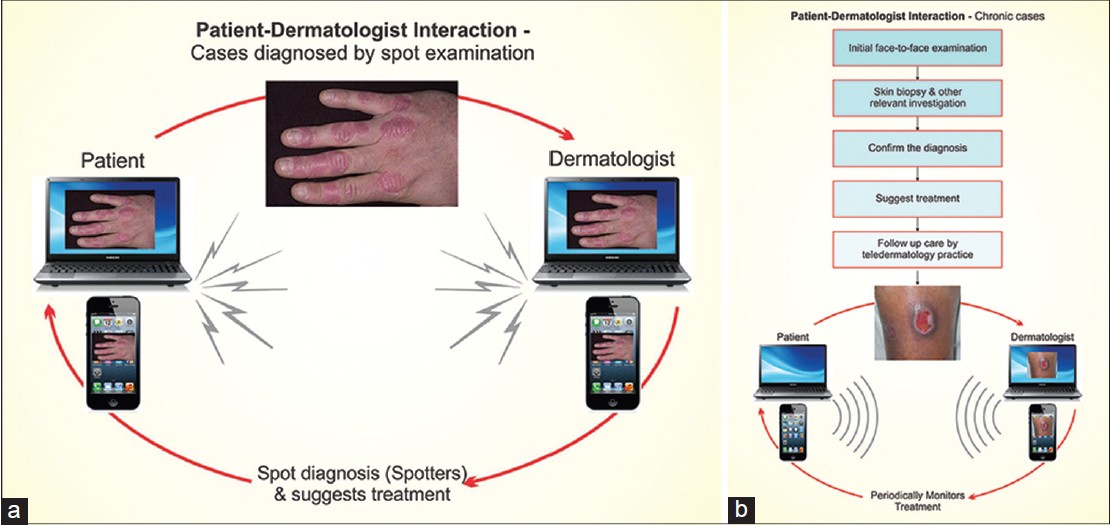

Patient-assisted teledermatology practice enables patient to upload images of any dermatological condition and seek the opinion of skin experts. The images of certain cases, which are sent by the patient, are diagnosed instantly by spot examination (spotters) by the dermatologist and treatment is offered.[Figure - 2]a. Many studies have confirmed that feasibility and diagnostic accuracy for teledermatology practice have been excellent. [33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39] In addition, chronic dermatologic conditions that are characterized by periodic flares, waxing and waning e.g. psoriasis, acne, leprosy or conditions like leg ulcers and vitiligo can be provided the frequent follow-up care that is required by patient-assisted teledermatology practice. Initial face-to-face examination is performed by the dermatologist. He identifies the suspected chronic cases, performs skin biopsy, and other relevant investigations in the first visit. He confirms the diagnosis and suggests treatment. Subsequently, systematic and periodic follow-up care is provided by teledermatology practice [Figure - 2]b. Braun et al., in 2004, demonstrated the use of mobile teledermatology for leg ulcers. [14] Kanthraj, in 2005, analyzed previous studies on this subject [14],[40],[41] and proposed the concept of integration of the internet, mobile phones, digital photography, and computer-aided design software to achieve telemedical wound measurement and care. [42] It incorporates capture, transfer, and measurement of digital images on a standard grid. [43] Mapping the extensive skin lesions like psoriasis [40] and tracing the small lesions [41] like leg ulcers and vitiligo along with the periodic measurement of their dimensions using computer software will aid in follow up care. The area (length and breadth) and the perimeter (the length of the circumference) of the lesions are obtained by computerized software. A periodic audit of the lesions provides best assessment of a chronic case like vitiligo or leg ulcer. The process records periodic changes in area, perimeter and percentage of regression of the ulcer and serves as an objective assessment to deliver follow-up care. [44],[45] Computerized assessments of psoriasis area severity index (PASI), [3],[33],[41] atopic dermatitis, [46] hand eczema, [47] and leg ulcers make it possible to deliver teledermatology follow up care using a standard scoring system. Patient-assisted teledermatology practice delivered effective follow up care in high-need patients with psoriasis after etanercept treatment. Further, severity measurements in psoriasis obtained by a clinical dermatologist and teledermatologists displayed strong correlation. [33] Thus, mobile teledermatology is a feasible method for monitoring disease severity in patients with psoriasis and teledermatology assessments were in accordance with PASI assessments. Recently, an online PASI training video as a user friendly model has been developed for measuring the severity of psoriasis [48] measure. Variation in scoring among dermatologists can be ameliorated by effective training modules. [48],[49]

|

| Figure 2: (a) Steps involved in patient-assisted teledermatology practice for cases diagnosed by spot examination. (b) Steps involved in patient-assisted teledermatology practice for chronic cases that require frequent follow-up |

The monitoring of leg ulcers [50] has been improved by the use of point counting and planimetry techniques. Serial tracings of ulcer margins can be used to accurately measure the area and perimeter of ulcers with the aid of computerized software. Recently, the acquisition of images by digital cameras has been replaced by smart phones with mobile applications. [51],[52] One such application is the Burnbook Apps which has been used to serially image and analyze burn wounds. [51] Similar apps used in conjunction with recent android technology-based smart cellular phones with high resolution digital cameras will make it easier to capture and transfer serial images of leg ulcers and facilitate patient-assisted teledermatology practice and make it feasible.

Patient-assisted teledermatology practice may be an effective tool for older people with chronic disorders who have difficulty making repeated visits to the dermatologist′s clinic. In this sub- specialty of geriatric dermatology, the dermatologist initially examines the patient in a traditional, face-to-face consultation, diagnoses the condition and advises treatment. [12],[39] However, subsequent follow-up care is provided by the dermatologist after analyzing the images sent by the patients or their care takers.

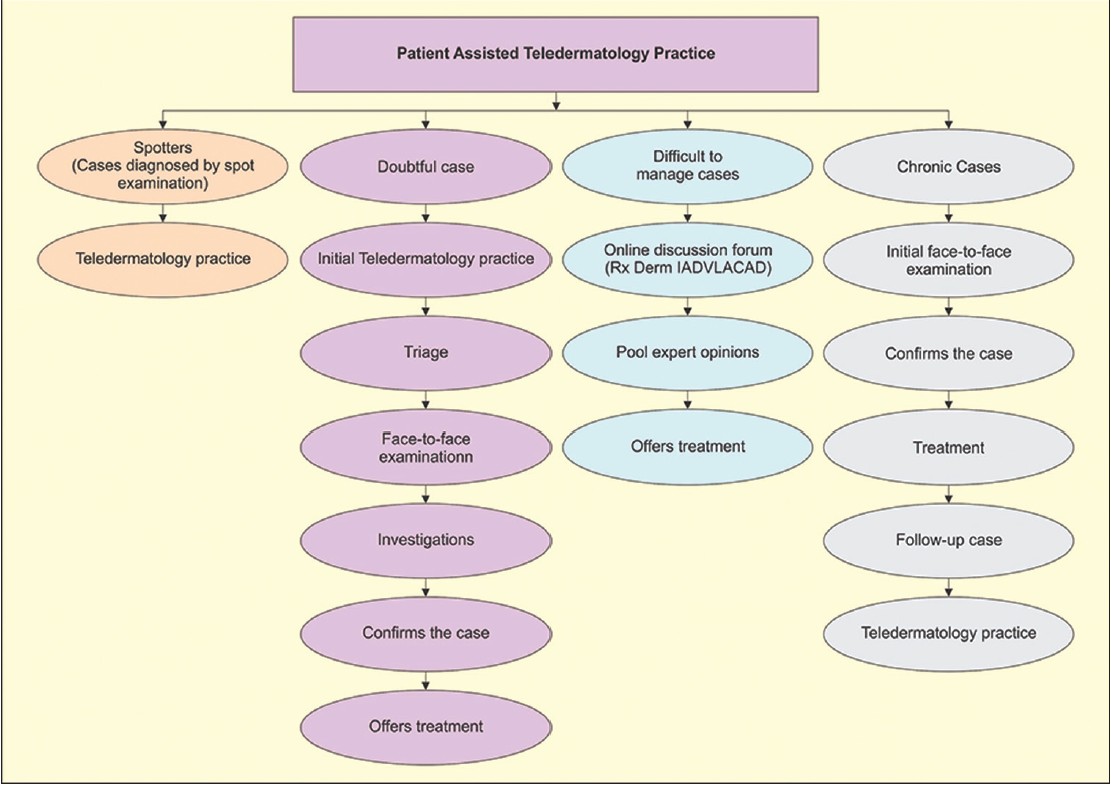

It should be recognised that the medico-legal principles of traditional consultation apply equally to teledermatology practice and care must be taken to provide appropriate advice and treatment in an efficient manner. [6] The most appropriate of the following approaches must be applied in patient-assisted teledermatology practice, (i) only teledermatology, when the dermatologist is sure of the diagnosis, i.e. in a case that can be diagnosed by spot examination, and offers treatment based on this assessment, (ii) initial teledermatology consultation for patient triage, followed by face-to-face examination in difficult cases; the dermatologist then performs investigations, confirms the diagnosis and offers treatment (iii) initial face-to-face examination followed by teledermatology practice to deliver follow-up care in chronic cases, and (iv) in difficult-to-manage cases that despite relevant investigations remain doubtful, the dermatologist may seek the opinion of experts in online discussion forums before offering a final diagnosis and treatment. Examples of such fora include acad_iadvl@yahoogroups.com-an e-mail group of the Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists, and Leprologists or Rxderm [Figure - 3].

|

| Figure 3:Various methods involved to manage cases in patient-assisted teledermatology practice |

Application of the acronym CAP-HAT to patient-assisted teledermatology practice

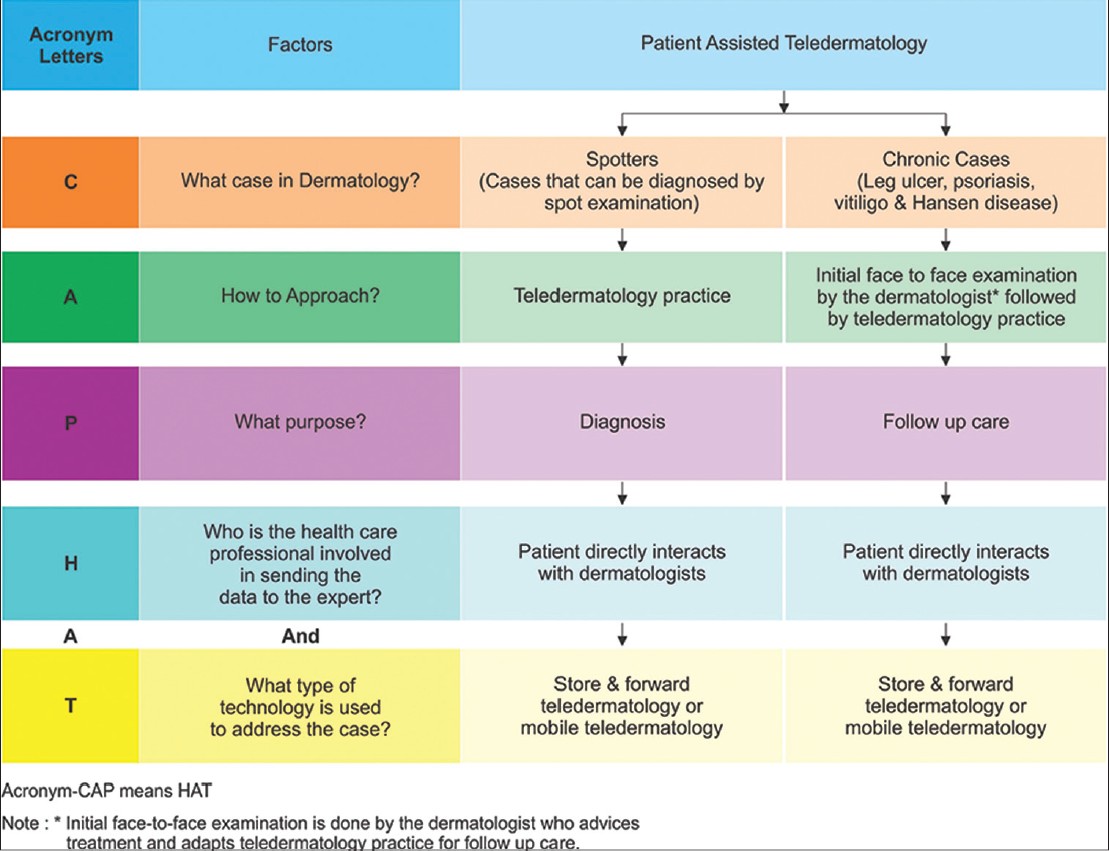

The acronym CAP-HAT, proposed in 2009 is used to list the five important cardinal factors that are required for teledermatology practice. [3] The acronym is the constellation of five cardinal factors: Presenting dermatology case (C), approach (A), purpose (P), health care professionals (H), involved, and type of teledermatology tools (T) used to deliver teledermatology practice. Teledermatology practice for various dermatological conditions that can manifest as easily diagnosed "spotters", pigmented skin lesions/melanoma and difficult-to- manage cases have been described using this acronym. [2],[3]

Patient-assisted teledermatology practice is encapsulated in the acronym CAP-HAT as illustrated in [Figure - 4]. Patient-assisted teledermatology practice is applied for the diagnosis of spotters and provide follow-up care for chronic cases, respectively. Patients can directly interact with the dermatologists using store and forward teledermatology or mobile teledermatology. Chronic dermatology cases like psoriasis, vitiligo, leg ulcer and Hansen disease that require follow-up care are approached by initial face-to-face examination by the dermatologist, who advises treatment and adopts teledermatology practice for follow-up care [Figure - 4].

|

| Figure 4:Application of the CAP-HAT acrnym for patient-assisted teledermatology practice |

Requirements for patient-assisted teledermatology practice

The criteria for a patient to participate in the patient-assisted teledermatology practice are as follows: (i) Proper filling of patient history forms provided on the Internet, with or without help. (ii) Should be able to upload the electronic images of their skin disorder, and (iii) Adoption of treatment advice given by the dermatologist during initial face-to-face examination as a part of teledermatology practice for future follow up.

Surveys have shown that patient-assisted teledermatology practice is clinically feasible both for patients and dermatologists. [7],[53] Patient-assisted teledermatology practice using a mobile teledermatology tool was found to be an acceptable method by HIV positive patients. [53] Moreover, patient-assisted teledermatology practice breaks the barriers associated with dermatology care such as cost and distance. Further, various clinical reports have demonstrated that treatment satisfaction and quality of care was high in mobile teledermatology consultations with a face-to-face interaction. Patients were willing to undertake mobile teledermatology consultations requiring clinical images of chest, legs, genitals, and face. [53] Besides, there exists a significant difference for patient willingness to mobile consultation involving lesions on the face versus compared with their willingness when other body sites were involved.

CONCLUSION

Cases that can be diagnosed by spot examination ("spotters") achieve the best diagnostic accuracy and are ideal for patient-assisted teledermatology practice. A dermatologist can perform initial face-to-face examination and confirm the diagnosis followed by teledermatology practice to deliver follow-up care for chronic cases like psoriasis and leg ulcers. Online severity measurements for psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and ulcers are documented to be valid. Applications need to be developed and tailored to the requirements of patient-assisted teledermatology practice. Influx of android technology and its applications allow for consistency in capturing and transferring images, and measuring severity thus facilitating periodic serial monitoring of images to deliver follow up care. In other applications of teledermatology, a dermatologist may use an online discussion forum to seek expert opinion on diagnosis and treatment of difficult-to-manage cases. The standardization of patient-assisted teledermatology practice can be a catalyst to improve dermatological health care across the country.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am thankful to the Indian Society of Teledermatology (INSTED) and Special interest group (SIG) Teledermatology of the Indian Association of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy (IADVL) and J. S. S. University, Mysore for their constant academic encouragement rendered in completion of this project.

| 1. |

Perednia DA, Brown NA.Teledermatology: One application of telemedicine.Bull Med LibrAssoc 1995;83:42-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Kanthraj GR.Newer insights in teledermatology practice.Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:276-87.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Kanthraj GR.Classification and design of teledermatology practice: What dermatoses? Which technology to apply?J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:865-75.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Edison KE, Dyer JA.Teledermatology in Missouri and beyond.Mo Med 2007;104:139-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Massone C, Wurm EM, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Soyer HP.Teledermatology: An update. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2008;27:101-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Eedy DJ, Wootton R.Teledermatology: A review. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:696-707.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Eminovic N, Witkamp L, de Keizer NF, Wyatt JC. Patient perceptions about a novel form of patient-assisted teledermatology. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:648-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Hailey D, Roine R, Ohinmaa A. Systematic review of evidence for the benefits of telemedicine.J Telemed Telecare 2002;8 Suppl 1:1-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Binder B, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Salmhofer W, Okcu A, Kerl H, Soyer HP.Teledermatological monitoring of leg ulcers in cooperation with home care nurses. Arch Dermatol2007;143:1511-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Chen TS, Goldyne ME, Mathes EF, Frieden IJ, Gilliam AE. Pediatric teledermatology: Observations based on 429 consults. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:61-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Heffner VA, Lyon VB, Brousseau DC, Holland KE, Yen K. Store-and-forward teledermatology versus in-person visits: A comparison in pediatric teledermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:956-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Rubegni P, Nami N, Cevenini G, Poggiali S, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Massone C, et al. Geriatric teledermatology: Store-and-forward vs. face-to-face examination.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:1334-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Romero G, Sánchez P, García M, Cortina P, Vera E, Garrido JA. Randomized controlled trial comparing store-and-forward teledermatology alone and in combination with web-camera videoconferencing. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010;35:311-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Braun RP, Vecchietti JL, Thomas L, Prins C, French LE, Gewirtzman AJ, et al. Telemedical wound care using a new generation of mobile telephones: A feasibility study. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:254-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Kanthraj GR. A longitudinal study of consistency in diagnostic accuracy of teledermatology tools. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013;79:668-78.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Vañó-Galván S, Hidalgo A, Aguayo-Leiva I, Gil-Mosquera M, Ríos-Buceta L, Plana MN, et al.Store-and-forward teledermatology: Assessment of validity in a series of 2000 observations. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2011;102:277-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Ribas J, Cunha Mda G, Schettini AP, Ribas CB. Agreement between dermatological iagnoses made by live examination compared to analysis of digital images. An Bras Dermatol 2010;85:441-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Pak H, Triplett CA, Lindquist JH, Grambow SC, Whited JD.Store-and-forward teledermatology results in similar clinical outcomes to conventional clinic-based care. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:26-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Nordal EJ, Moseng D, Kvammen B, Løchen ML. A comparative study of teleconsultations versus face-to-face consultations. J Telemed Telecare 2001;7:257-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Taylor P, Goldsmith P, Murray K, Harris D, Barkley A. Evaluating a telemedicine system to assist in the management of dermatology referrals. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:328-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Gilmour E, Campbell SM, Loane MA, Esmail A, Griffiths CE, Roland MO, et al. Comparison of teleconsultations and face-to-face consultations: Preliminary results of a United Kingdom multicentreteledermatology study. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:81-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Oakley AM, Reeves F, Bennett J, Holmes SH, Wickham H. Diagnostic value of written referral and/or images for skin lesions. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12:151-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Lozzi GP, Soyer HP, Massone C, Micantonio T, Kraenke B, Fargnoli MC, et al. The additive value of second opinion teleconsulting in the management of patients with challenging inflammatory, neoplastic skin diseases: A best practice model in dermatology? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:30-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Ríos-Yuil JM. Correlation between face-to-face assessment and telemedicine for the diagnosis of skin disease in case conferences. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2012;103:138-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Salmhofer W, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Gabler G, Rieger-Engelbogen K, Gunegger D, Binder B, et al. Wound teleconsultation in patients with chronic leg ulcers.Dermatology 2005;210:211-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Frühauf J, Schwantzer G, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Weger W, Ahlgrimm-Siess V, Salmhofer W, et al. Pilot study on the acceptance of mobile teledermatology for the home monitoring of high-need patients with psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol 2012;53:41-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Whited JD, Hall RP, Foy ME, Marbrey LE, Grambow SC, Dudley TK, et al. Patient and clinician satisfaction with a store-and-forward teledermatology consult system. Telemed J E Health 2004;10:422-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Williams TL, Esmail A, May CR, Griffiths CE, Shaw NT, Fitzgerald D, et al. Patient satisfaction with teledermatology is related to perceived quality of life. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:911-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Fieleke DR, Edison K, Dyer JA.Pediatric teledermatology--a survey of current use.Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:158-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Hsueh MT, Eastman K, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ, Reiber GE. Teledermatology patient satisfaction in the Pacific Northwest. Telemed J E Health 2012;18:377-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Frühauf J, Kröck S, Quehenberger F, Kopera D, Fink-Puches R, Komericki P, Pucher S, Arzberger E, Hofmann-Wellenhof R.Mobile teledermatology helping patients control high-need acne: A randomized controlled trial.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Sep 26. doi: 10.1111/jdv. 12723. [Epub ahead of print].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Philp JC, Frieden IJ, Cordoro KM. Pediatric teledermatology consultations: Relationship between provided data and diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30:561-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Koller S, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Hayn D, Weger W, Kastner P, Schreier G, et al. Teledermatological monitoring of psoriasis patients on biologic therapy. Acta Derm Venereol 2011;91:680-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Frühauf J, Schwantzer G, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Weger W, Ahlgrimm-Siess V, Salmhofer W, et al.Pilot study using teledermatology to manage high-need patients with psoriasis.Arch Dermatol 2010;146:200-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Schreier G, Hayn D, Kastner P, Koller S, Salmhofer W, Hofmann-Wellenhof R. A mobile-phone based teledermatology system to support self-management of patients suffering from psoriasis.ConfProc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2008;2008:5338-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Nami N, Massone C, Rubegni P, Cevenini G, Fimiani M, Hofmann-Wellenhof R.Concordance and Time Estimation of Store-and-forward Mobile Teledermatology Compared to Classical Face-to-face Consultation.Acta Derm Venereol. 2014; 95:35-39.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Watson AJ, Bergman H, Williams CM, Kvedar JC. A randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of online follow-up visits in the management of Acne. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:406-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Trindade MA, Wen CL, Neto CF, Escuder MM, Andrade VL, Yamashitafuji TM, et al.Accuracy of store-and-forward diagnosis in leprosy.J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:208-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Salmhofer W, Binder B, Okcu A, Kerl H, Soyer HP. Feasibility and acceptance of telemedicine for wound care in patients with chronic leg ulcers. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12 Suppl 1:15-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Kanthraj GR, Srinivas CR, Shenoi SD, Deshmukh RP, Suresh B. Comparison of computer-aided design and rule of nines methods in the evaluation of the extent of body involvement in cutaneous lesions. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:922-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Kanthraj GR, Srinivas CR, Shenoi SD, Suresh B, Ravikumar BC, Deshmukh RP.Wound measurement by computer-aided design (CAD): A practical approach for software utility. Int J Dermatol 1998;37:714-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Kanthraj GR. The integration of the internet, mobile phones, digital photography, and computer-aided design software to achieve telemedical wound measurement and care. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:1470-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Kanthraj GR, Srinivas CR. Store and forward teledermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:5-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Chanussot-Deprez C, Contreras-Ruiz J. Telemedicine in wound care.Int Wound J2008;5:651-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Mayrovitz HN, Soontupe LB. Wound areas by computerized planimetry of digital images: Accuracy and reliability. Adv Skin Wound Care 2009;22:222-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Tripodi S, Panetta V, Pelosi S, Pelosi U, Boner AL. Measurement of body surface area in atopic dermatitis using specific PC software (Scorad Card). Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2004;15:89-92.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Baumeister T, Weistenhöfer W, Drexler H, Kötting B. Spoilt for choice--evaluation of two different scoring systems for early hand eczema in teledermatological examinations. Contact Dermatitis 2010; 62:241-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Armstrong AW, Parsi K, Schupp CW, Mease PJ, Duffin KC. Standardizing training for psoriasis measures: Effectiveness of an online training video on Psoriasis Area and Severity Index assessment by physician and patient raters. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:577-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Swerlick RA.Practice gaps. Inconsistency in clinical measurements can be improved through training: Comment on "Standardizing training for psoriasis measures". JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149:582-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Bowling FL, King L, Fadavi H, Paterson JA, Preece K, Daniel RW, et al. An assessment of the accuracy and usability of a novel optical wound measurement system. Diabet Med 2009;26:93-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Godwin ZR, Bockhold JC, Webster L, Falwell S, Bomze L, Tran NK. Development of novel smart device based application for serial wound imaging and management. Burns 2013;39:1395-402.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 52. |

Brewer AC, Endly DC, Henley J, Amir M, Sampson BP, Moreau JF, et al.Mobile Applications in Dermatology.JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:1300-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 53. |

Azfar RS, Weinberg JL, Cavric G, Lee-Keltner IA, Bilker WB, Gelfand JM, et al.HIV-positive patients in Botswana state that mobile teledermatology is an acceptable method for receiving dermatology care. J Telemed Telecare 2011;17:338-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

6,861

PDF downloads

3,821