Translate this page into:

Pattern of dermatoses among inmates of district prison- Mangalore

Correspondence Address:

Mohammed Ismail Shaikh

7/23, A, Grant Bldg, Arthur Bunder Road, Colaba, Mumbai-400 005

India

| How to cite this article: Kuruvila M, Shaikh M, Kumar P. Pattern of dermatoses among inmates of district prison- Mangalore. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002;68:16-18 |

Abstract

The present paper studies the pattern of dermatoses among 225 inmates of a jail, over a period of 6 months (Feb- July' 99). 63.6% inmates screened had dermatoses. Among those with dermatoses 63.3% were infectious and 36.4% were non-infectious. Among the infections, fungal infections (51.3%) constituted the maximum. Pediculosis copitis was found in 6.6% of inmates. in the non-infectious group, pigmentary changes (21%) and dandruff (21%) were noted. Overcrowding prevalent in jail (73% excess inmates) could be contributory factor for the high incidence of infections.

|

|

|

|

Introduction

Jails and prisons have existed in society since time immemorial and serve to hold the under-trials and convicts. Rampant overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions provide a favourable breeding ground for various infections, including skin diseases.

This population is an underserved section of the society and often their healthproblems are neglected. The prison population is a cesspool for diseases and if inmates are not treated adequately in jails; they will return to the community and further burden the existing health care facilities.

The place of study is District PrisonMangalore; which is mainly for undertrials. It is situated in the heart of Mangalore city, and houses an average of 250 inmates (actual capacity-130). It was established in 1859 and is spread over 11.7 acres. It has 6 large dormitory type barracks, besides many individual cells.

A health care programme exists in the jail. Every prisoner is quarantined for 14 days at the time of entry and subsequently relocated to barracks or cells as the case warrants. A government doctor visits the jail every 2 weeks. In spite of extensive studies done abroad in Health Care in Correctional facilities,[1],[2],[3] similar data are lacking in India. Our study is aimed at filling this lacuna and gaining an insight into prevalence of skin diseases among the inmates of a District Prison and assess the usefulness of mass screening in immediate diagnosis and treatment of common skin conditions.

Materials and Methods

A total of 225 inmates of the district prison Mangalore were screened over 6 months from February to July-1999 within the prison premises. All the inmates were subjected to a detailed cutaneous examination in good day-light. A brief history pertaining to the skin complaints was elicited. Basic investigations like scraping for fungus and microscopic examination of hair for nits were done. Patients were given treatment and referred to the district Wenlock hospital for further investigations whenever required.

Results

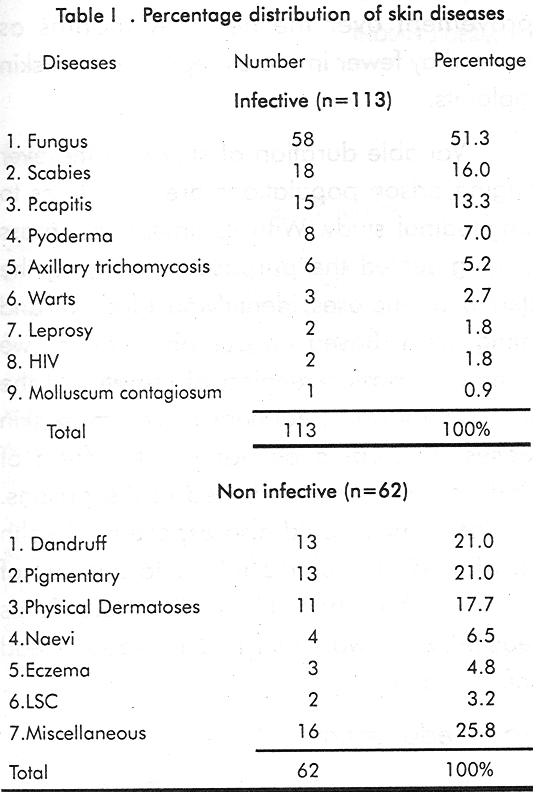

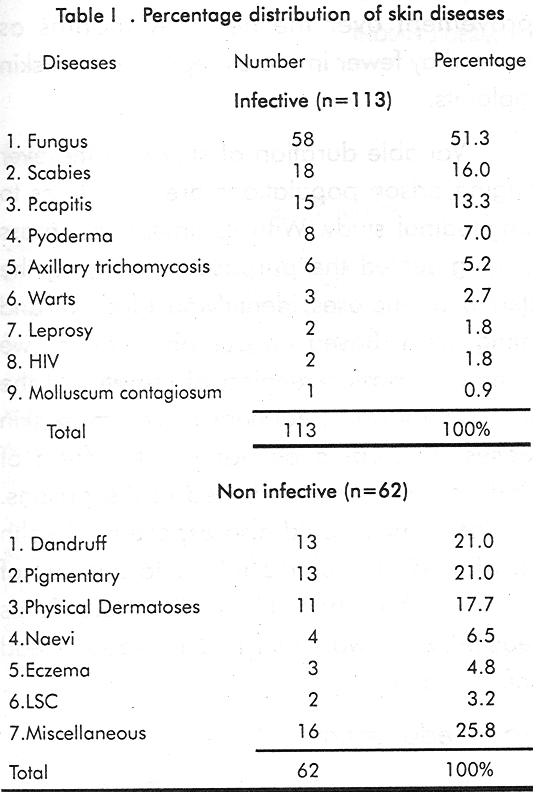

A total of 225 inmates were screened, among which majority 223(99%) were males and 2 were females. Age group ranged from 15 to 74 years with maximum number of inmates 101 (44.9%) belonging to 25 to 34 years. 143(63.6%) inmates had dermatoses while 82 (36.4%) had none. Among those with dermatoses, 91(63.6%) had infectious while 52(36.4%) had non-infectious dermatoses; 22 had more than one infection. Among the non infectious dermatoses (n= 113), 58(51.3%) were superficial dermatophyte infections, 18(16%) were scabies and 15(13.3%) were pediculosis capitis. The overall prevalence of infectious dermatoses was 40.4% (91/225) of inmates. Among the non-infectious dermatoses (n=62), dandruff 13 (21 %) and pigmentary changes 13 (21%) were the commonest [Table - 1]. 2 cases each, HIV and Hansen′s disease were detected and referred to, Government Wenlock Hospital. One case was subsequently diagnosed as borderline tuberculoid leprosy and started on paucibacillary multi-drug therapy. The other case was lost to follow-up as he got transferred to another prison.

Jail is a facility meant for those awaiting trial. Hence, majority of inmates are incarcerated for 1-3 months, after which they are either released or transferred to higher prisons.Analysis revealed that the percentage of infections 53/ 113(47%) is maximum in the initial 1-3 months, after which it declines rapidly; then it slowly rises again to a second peak of 17/1 13 (15%) at 69 months duration of stay. [Figure - 1].

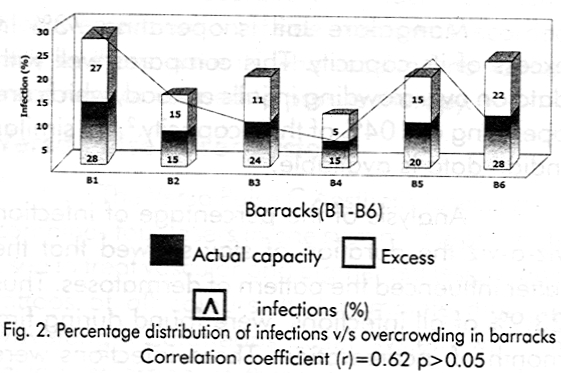

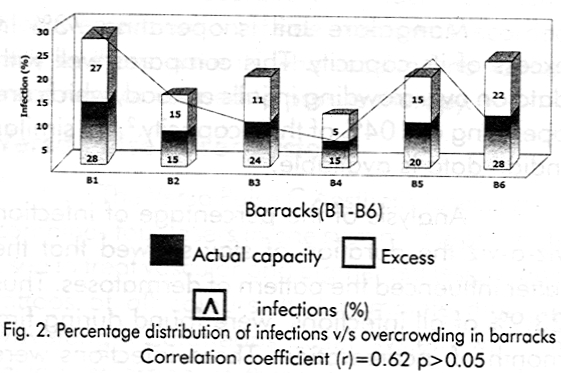

Overcrowding is rampant (capacity: 130, occupancy: 225). There were 73% excess inmates (excess/ capacity X 100) housed in various barracks. Barracks with overcrowding showed high percentage of infection; correlation coefficient (r)=0.62 (p> 0.05) [Figure - 2].

Discussion

Overcrowding coupled with the hot and humid climate of Mangalore forms an ideal mileau for infections. Prevalance of infections was 40.4%. Among the infections, fungal infection was the commonest (51.3%). The commonest clinical type was tinea cruris (43.1%). Hot and humid climate prevailing during our study period, may have contributed to this. Kandhari and Sethi have reported that dermatomycoses were common in hot and humid climate from May to September.[4]

Scabies was the second commonest infectious dermatoses (16%). Sleeping crowded together may have contributed to this. Pediculosis capitis comprised 6.6% of all infections. Lice are more common in children than adults and females of all age-group are more commonly affected, In our study the higher prevalence of pediculosis capitis among this male adult population could be explained by their habits of sharing combs, bath-towels and overcrowding. Two cases of Hansen′s disease were detected. This assumes importance in the current scenario of leprosy elimination. Jails and prisons are beyond the preview of leprosy workers, and may be hidden pockets for Hansen′s disease. Considering the socio-economic background, literacy level and way of life, these cases may escape detection even after their release. Hence, survery of prisons by qualified personnel will be useful in detecting these cases.

Mangalore Jail is operating 73% in excess of its capacity. This compares well with data on overcrowding in jails abroad, which are operating at 104% of their capacity.[2] No similar Indian data is available.

Analysis of the percentage of infection viz-a-viz the duration of stay show4ed that the latter influenced the pattern of dermatoses. Thus 23.9% of all infections were found during first month of incarceration. These infections were probably acquired in the community. Incubation period of scabies and life-span of pediculus capitis correlates with the symptomatology appearing during the initial first month of stay. Overcrowding and frequent rotation of inmates among different barracks led to the spread of infections. This pool of infections persists, self perpetuates and reaches its peak (47.7%) over the next 3 months. After 3 months most of the inmates leave and this corresponds to the fall of infections.

The infection- rate then slowly rises again to attain a second peak (15%) at 6-9 months. This may be due to chronicity of the infections. Most of the infections could be rapidly diagnosed and treated. There was an overall improvement over the next few months as evidenced by fewer immates reporting with skin complaints.

Variable duration of stay and the ever changing prison populations are limitations to a longitudinal study. With its limitations, mass screening served the purpose of studying the pattern of dermatoses, identifying infections and treating them. Based on our observations we recommend mass screening of inmates at the point of entry and treatment of common skin diseases. This could be done in the form of periodic skin camps conducted in the prisons. Such skin camps would also expose the health professionals from all disciplines to a group of patients who have had little medical care. Steps to reduce overcrowding will help to reduce spread of infections in jail.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. A Rajeev, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Kasturba Medical College Mangalore, for his help in statistical analysis and compilation of data.

| 1. |

Council on scientific affairs: Health status of detained and incarcerated youth. JAMA 1990;263:987-991.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

American college of physicians, National commission on correctional health care, and American Correctional health service association: The crisis in correctional health care; the impact of the drug control strategy on correctional health services: Annals Intern Med 1992; 117: 71-76.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Correctional health care: A public health opportunity: Annal Intern Med 1993; 118:139-145.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Kadhari KC, Sethi KK. Dermatophytosis in Delhi area. J Indian Med Assoc 1964;42:324.

[Google Scholar]

|