Translate this page into:

Pediatric contact dermatitis

Correspondence Address:

Vinod K Sharma

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi - 110 029

India

| How to cite this article: Sharma VK, Asati DP. Pediatric contact dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010;76:514-520 |

Abstract

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in children, until recently, was considered rare. ACD was considered as a disorder of the adult population and children were thought to be spared due to a lack of exposure to potential allergens and an immature immune system. Prevalence of ACD to even the most common allergens in children, like poison ivy and parthenium, is relatively rare as compared to adults. However, there is now growing evidence of contact sensitization of the pediatric population, and it begins right from early childhood, including 1-week-old neonates. Vaccinations, piercing, topical medicaments and cosmetics in younger patients are potential exposures for sensitization. Nickel is the most common sensitizer in almost all studies pertaining to pediatric contact dermatitis. Other common allergens reported are cobalt, fragrance mix, rubber, lanolin, thiomersol, neomycin, gold, mercapto mix, balsum of Peru and colophony. Different factors like age, sex, atopy, social and cultural practices, habit of parents and caregivers and geographic changes affect the patterns of ACD and their variable clinical presentation. Patch testing should be considered not only in children with lesions of a morphology suggestive of ACD, but in any child with dermatitis that is difficult to control.Introduction

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in children, until recently, was considered rare. [1],[2] ACD was considered as a disorder of the adult population and children were thought to be spared due to a lack of exposure to potential allergens and an immature immune system. Prevalence of ACD to even the most common allergens in children, like poison ivy and parthenium, is relatively rare as compared to adults. [2] However, there is now growing evidence of contact sensitization of the pediatric population, and it begins right from early childhood, including 1-week-old neonates. [3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11] Vaccinations, piercing, topical medicaments and cosmetics in younger patients are potential exposures for sensitization. [1] The pattern of allergen exposure and patch test results may vary over time. [12] The reported rates of positive patch test in various series in children with suspected ACD ranges from 32.6% to 67%. [3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10] This broad range could be due to different age groups, methods and different antigens tested in various studies.

The consequences of undiagnosed and untreated ACD in children and in their family can be severe. Loss of sleep due to uncontrolled itching, absence at school, feeling of inferiority among the peer groups and irritability can be found in children suffering from chronic severe dermatitis. [13]

Epidemiology

It is important to be aware of the frequency of contact dermatitis in children. Otherwise, dermatitis in children is often classified as atopic or endogenous in origin. To study the frequency of ACD in children, one should be cautious as the prevalence of positive patch tests in population-based studies is different from the prevalence of ACD (positive patch test with clinical correlation) in patients referred for patch testing. [14] Among children with suspected contact dermatitis referred for patch testing, positive patch test rates have ranged from 14% to 70%. Of these, about 56-93% have been thought of current relevance. [12],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20] In contrast, there are some population-based patch test studies of unselected pediatric patients (sample size 85-1,146 patients per study), where positive patch test rates ranged from 13% to 24%, significantly lower than the rates seen in patients selected for suspected contact dermatitis. [15],[21],[22],[23] The largest of these studies, which also provides specific relevance information, found the prevalence of past or current relevant reactions to be 7%, with a higher risk seen in females. [23] The most common sensitizers were nickel (8.6%, relevance 69%) and fragrance mix (1.8%, relevance 29%). [23] Another difference among various studies is accepting macular erythema as a positive test. For example, macular type of reactions represented 29% of all relevant positive patch tests in the study by Hammmonds et al.[1] In other studies, macular erythema was not consistently regarded as a positive test.

There is no published data of childhood ACD from Indian population as far as ascertained. However, an unpublished data from AIIMS, New Delhi, found 16 children below 20 years age suspected to have ACD among 440 patients (2.96%) referred for patch testing. Eight children (50%) had positive patch tests, the most common sensitizer being nickel (seven patients), followed by fragrance mix (three patients) and paraben mix, potassium dichromate, cobalt and formaldehyde (one each).

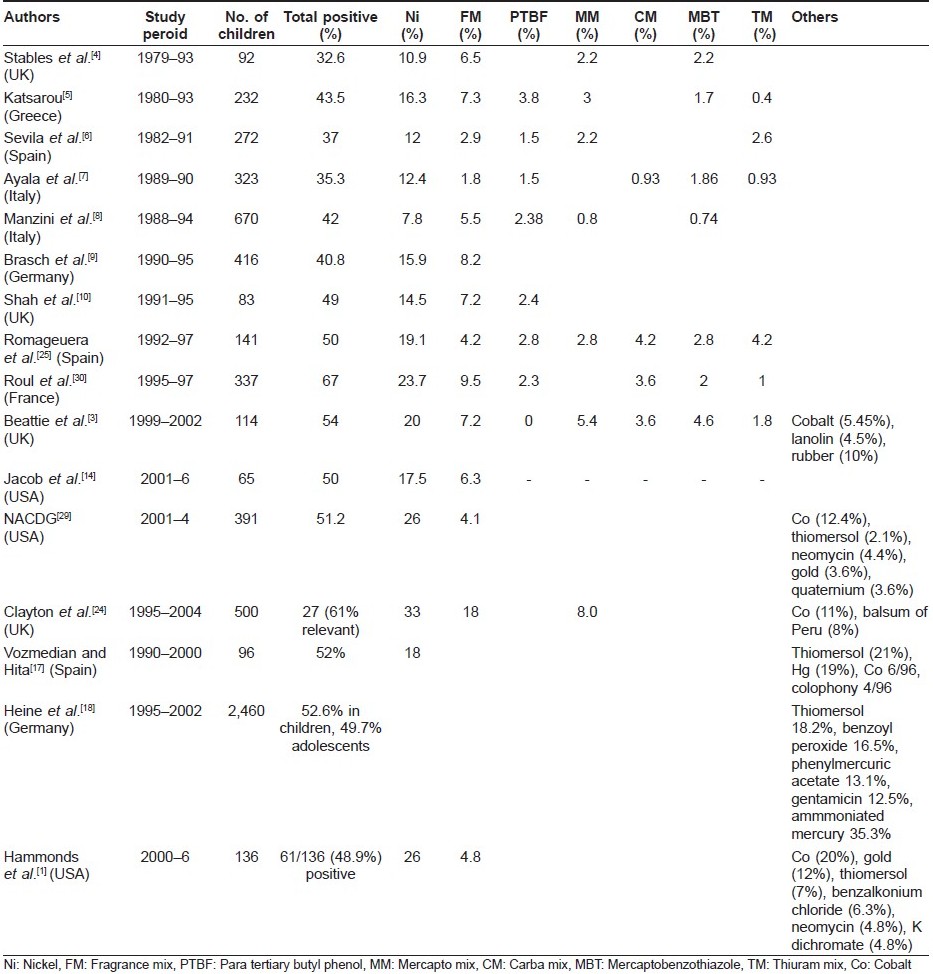

Common Allergens in Children

Nickel is the most common sensitizer in almost all studies pertaining to pediatric contact dermatitis. Other common allergens [Table - 1] reported are cobalt, fragrance mix, rubber, lanolin, thiomersol, neomycin, gold, mercapto mix, balsum of Peru and colophony. [2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[14],[17],[18],[24],[25] Pattern of ACD in children is changing over time. For example, contact dermatitis to the toxicodendron family was more common than nickel or rubber in the United States about a decade ago, but now nickel positivity has exceeded others. [2]

Patch Testing in Children

Patch testing has been restricted previously in the children because of the technical difficulty with their small physical size and the belief that irritant reactions dominate in children, leading to extensive false-positive results. [2] Jacob et al. and Johnke et al. raised questions about the reliability of the adult patch test methodology used in the pediatric population. [26],[27] Johnke et al. suggested that infants may need lower nickel concentrations for testing. [27]

However, Storrs [28] studied about the need of adjustments in the method of patch testing in children as opposed to adults and concluded that standard methods used in adults are safe as well as reliable in children, [8] although individualization of test battery according to local and temporal needs may be desirable. Children′s small backs may require sequential patch test applications to test all potentially important allergens. Similarly, Mortz and Andersen reviewed 17 studies of a total of 5,728 children and confirmed the general opinion that children can be patch tested with the same concentrations as adults. [20] This concept has also been supported by other groups. [29] Authors agree with the view that similar patch test concentrations as adults can be used till the time specific recommendations for the pediatric population are available.

Factors Affecting the Prevalence and Patterns of Contact Sensitization in Children

Different factors like age, sex, atopy, social and cultural practices, habit of parents and caregivers and geographic changes affect the patterns of ACD and their variable clinical presentation.

Effect of age difference

There is no consensus among different studies regarding the effect of age on the incidence of ACD in children. [14] A few studies noted an early peak in prevalence in children under the age of 3 years, [12],[30] while others found a generally increasing prevalence through adolescence. [6],[24],[31],[32],[33],[34] Another author found no significant differences between different age groups (3-10, 11-15, 16-18 years) in their study, although there was a trend in the males to have fewer positive reactions with increasing age (P = 0.18). [1] Similarly, no change by age was reported by Beattie et al.[3]

Regarding reaction to a specific allergen, nickel showed the most frequent and relevant positive reactions in the very young group (<5 years) in the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) study, while lanolin yielded positive reactions more frequently in children aged between 6 and 12 years (P <0.01). [29] Hammonds et al. reported nickel allergy to be more common in the younger patients and gold allergy in female patients. [1] But, Beattie et al. reported that most nickel allergic children were older in their study (median age, 13.5 years; range, 10.2-15.0 years). [3]

Fisher reported a 1-week-old infant with a strongly positive patch test reaction to epoxy resin, manifesting as band-like dermatitis above the wrist because of a vinyl band that was made of an epoxy resin. [34] It is possible to sensitize the newborn to poison ivy, and the sensitization rate increases with age. [35]

Sex

Significantly more girls (19.4%; 95% CI, 16.3-22.7%) than boys (10.3%; 95% CI, 7.8-13.2%) had more positive tests (P = 0.001) in the study by Mortz et al.[23] They also noticed that girls were more sensitized than boys to nickel, whereas no sex difference was found for other allergens. Clayton et al. also found girls to have a higher patch test positivity rate (odds ratio, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.41-0.95; P = 0.029). [24] However, in a large study of 1,094 children aged between 7 months and 12 years, the percentage of sensitized subjects did not show significant variations according to their sex. [12] Other studies share similar results. [16],[18],[22] ACD to cosmetics is also more common in teenage girls. [2]

Geographical variations

There are large variations in the patterns of childhood ACD reported from different countries. [35] For example, rhus was found to be the most common allergen in North California, but it is not seen in Europe, where these plants are not found. Mercurial compounds were the most common allergens in France while nickel, chromate and rubber were common in the Danish study. A Spanish study showed nickel, formaldehyde, neomycin and rubber as being the predominant allergens, which was different from that reported in the Polish study (nickel, cobalt, paraphenylene diamine, mercurial compounds and fragrance). [35] Unpublished data from AIIMS, New Delhi, found nickel to be the most common sensitizer in children followed by fragrance mix. Contact dermatitis could be a very common occupational hazard in India, as about 44 million children work and as many as 25,000 children are involved in the footwear and carpet industry and thus are exposed to various allergens like leather, rubber, formaldehyde and tanning, processing or dyeing agents. [36] It is understood that children with ACD in the work place have poor access to health care, resulting in a low prevalence in reports from India.

Occurrence of irritant reactions during patch testing

Irritant reactions in children are as common as in adults. [28],[29] The most common irritants include benzalkonium chloride (1.53%), cobalt (1.29%), cocamidopropyl betaine (0.52%) and nickel sulfate (0.51%). [29]

Role of atopy

In India, the prevalence of atopic dermatitis ranges between 10% and 15.6%. [37] While the association of the atopic diathesis triad (atopic skin disease, asthma and rhinitis) with a familial tendency is well accepted, the interaction between ACD and atopic dermatitis is still not clear. [13],[35] Atopic dermatitis is associated with a higher rate of contact allergy and irritancy due to disturbed barrier function, which may be wrongly interpreted as delayed hypersensitivity. It is possible therefore that the very high incidence of ACD in children reported by some authors, like the study by Roul et al., was a result of the very high number of atopics in their subjects (76%). [30] However, the rate of positive patch tests in atopics and non-atopics was similar. And, other workers have also reported that the rate of positive results in atopics is either similar or, in fact, lower than that in non-atopics. This might be due to difficulty in diagnosing contact allergy on a background of atopic dermatitis or due to less-stringent selection. [3],[12],[23],[29],[38] Moreover, atopic eczema may be an important risk factor for the development of ACD in children rather than in adults. In the study by the NACDG, of those with a reactive patch test, children (34.0%) were more likely than adults (11.2%) to have a final diagnosis that included atopic eczema. ACD to nickel and Kathon CG was more frequent in atopic children in the study by Seidenari et al.[12]

Atopic Patch Testing

Krupashankar et al. used a variant method of patch testing in 75 children with atopic dermatitis. [39] Prick test allergens were applied to the back and reading was performed after 48 and 72 h. Positive reactions were seen in 47% of the children; parthenium accounted for 42% of these. The antigens used were dust mites, D. farinae and D. pteronyssinus, pollens of Cynodon dactylon and Parthenium hysterophorus, foods like rice, wheat, milk, egg and dog and cat epithelia. Interestingly, among 15 parthenium atopic patch test-positive subjects, eight subjects were also tested with the Indian Standard Series and, of these, six subjects showed a positive reaction to parthenium (delayed hypersensitivity). They concluded that epicutaneous application of prick test antigen on intact skin can produce a reaction. [39]

Comparison with the Adult Population

There are few studies which compare specific allergen frequencies in the pediatric and adult populations. The frequency of at least one positive patch test in children and adults was similar in the study by NACDG. [29] Individual allergens that were statistically more frequent in children in that study included nickel (P < 0.001), cobalt chloride (P < 0.001) and thimerosal (P < 0.01), whereas those that were significantly less frequent in the pediatric compared with the adult populations included neomycin sulfate (P < 0.05), fragrance mix (P < 0.002), balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae) (P < 0.001) and quaternium 15 (P < 0.001). [29]

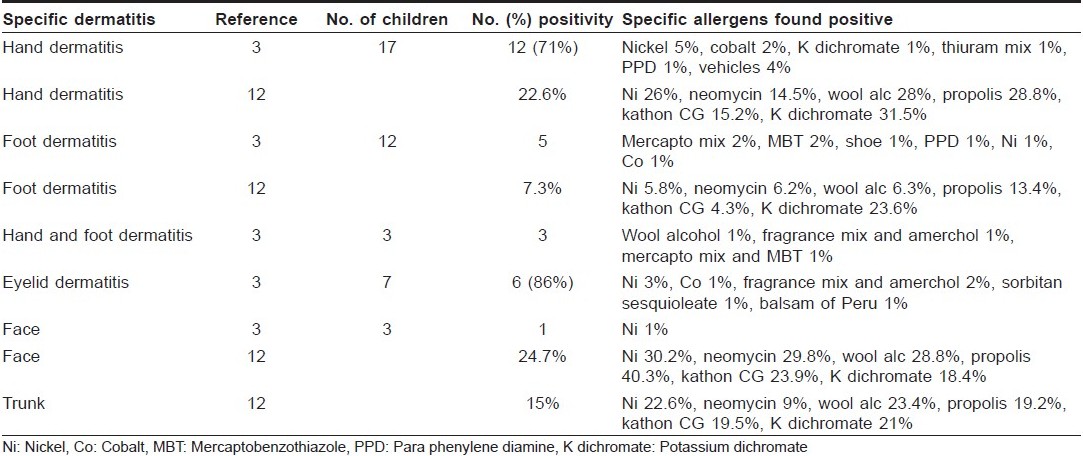

Dermatitis of Specific Parts of the Body and Correlation with Allergens

Only few studies differentiate the results of positive patch testing according to the site of dermatitis. Nickel remains the most frequent cause of ACD at any regional site [Table - 2]. Seidenari et al. found that a facial dermatitis prevailed in children positive to propolis, whereas the neck and the feet were more frequently involved in patients sensitized to Kathon CG and potassium dichromate, respectively. The flexural areas of the limbs were affected in children allergic to nickel and Kathon CG significantly more often than in neomycin-positive patients. [12] Beattie et al. found nickel, cobalt, potassium dichromate, thiuram mix, paraphenylene diamine (PPD) and vehicles to be the most common sensitizers on hands, while mercapto mix, mercaptobenzothiazole (MBT) and PPD were more common in cases of ACD involving the feet. They also reported nickel, fragrance mix, amerchol, sorbitan sesquioleate and balsam of Peru to cause dermatitis on the eyelids. [3] The face, hands and feet were the most common sites involved in ACD in children at AIIMS, New Delhi. Nickel and fragrance mix were common sensitizers on the face while nickel, chromate and cobalt were more common on the hands and feet (Unpublished data). Brar et al. studied the clinical profile of forefoot eczema in 42 Indian children and found that a majority of the patients (62%) were below the age of 20 years. Patch testing was performed in 19 (45.2) of the patients and three (15.7%) showed sensitivity to nickel, while two (10.5%) each showed sensitivity to gentamicin and framycetin. [40]

Common Presentations of ACD in Children

Allergens of particular importance to children include paraphenylene diamine, tosylamide formaldehyde resin and nickel. Nickel sensitivity is derived from ear piercing, use of bracelets, necklaces, rings and metallic zipper containing nickel. [2],[41] Many of the nickel reactions could be false-positives. Therefore, it is important to exclude all irritant reactions to nickel. Beattie et al. regarded only those reactions of grade 3 or more to be significant unless there was a clear history of reaction. [3] The authors attributed increase in ACD to nickel in children over the past decade to a trend for body piercing in teenagers over the last few years. They also found a greater incidence of allergy to rubber products than others, not only in those children who had foot dermatitis but also in children with atopic dermatitis or dermatitis elsewhere who were in contact with other rubber-containing products, mainly sports equipment. [3] A characteristic pattern of ACD to rubber compounds around the proximal thighs and waistline associated with the use of disposable napkins has been described as "Holster sign." [42],[43] Thiuram and carbamates used during the vulcanization process are more commonly implicated in patients with a history of contact dermatitis to gloves or balloons, while mercaptobenzothiazole and mercapto mix are found in "havier" rubber used in shoes. Shoe dermatitis presents as pruritic papular and oozy rash on the dorsum of toes, extending onto the feet and sparing the toewebs. It should be differentiated from juvenile contact dermatitis, which is a more common dermatosis in children. [2] Chromates used in the tanning process are also important allergens in leather shoes. Seidenari et al. suspected a high rate of contact sensitization to disperse dyes in childhood because of the wide employment of synthetic fibers in children′s garments. [12] PPD, which is used in permanent hair dyes and black henna, photographic developing agent, azo dyes, antioxidants and in rubber vulcanization, causes the majority of cases of contact dermatitis reported in children with black henna tattoos. [34] The fashion of temporary henna tattoos in children should be discouraged because of the serious consequences of sensitization to PPD in the future. [34] Other common cosmetics implicated in childhood ACD include deodorants, nail lacquers, lipsticks and eye makeup products. [2] The development of an allergy to thimerosal is likely a result of routine vaccination. [29]

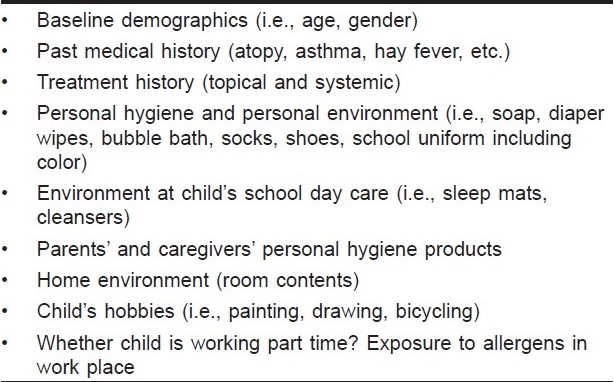

Important demographic and environmental history to be gathered in children with suspected ACD is summarized in [Table - 3]. [13]

Conclusions

Patch testing should be considered not only in children with lesions of a morphology suggestive of ACD, but in any child with dermatitis that is difficult to control. [3] Clayton et al. observed no statistical difference in the relationship between the site of primary dermatosis and a positive patch test result. [24] The pattern of the presenting dermatitis in children should not determine referral for patch testing. However, a suspect localization of skin lesions may be one of the indications for patch testing.

Prevalence rates for any one allergen change all the time. Patch testing to the standard series, medicaments and own products should detect most cases of ACD in children. [3] However, development of a pediatric screening series of allergens needs to be performed locally.

Lastly, it is important to remember that ′′there is only a partial concordance between a positive patch test and ACD." [20],[28] A positive patch test does not necessarily prove the presence of ACD; the determination of relevance is equally essential. For example, in a group of 304 infants tested to nickel and fragrance mix twice at 12 and 18 months, 26 children (8.6%) were nickel positive, but clinical relevance was found in only one child. [27] This failure to determine relevance is often seen in studies of ACD in both adults and children. [20],[28] This makes ascertaining the actual prevalence of clinical ACD in children difficult to determine. The authors′ experience suggests that patch test that persist at the 72- or 96-h readings give better correlation and are more relevant.

| 1. |

Hammonds LM, Hall VC, Yiannias JA. Allergic contact dermatitis in 136 children patch tested betweeen 2000 and 2006. Intern J Dermatol 2009;48:271-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Krafchik BR. Eczematous dermatitis. In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, editors. Pediatric Dermatology. 2 nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. p. 710-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Beattie PE, Green C, Lowe G, Lewis-Jones MS. Which children should we patch test? Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;32:6-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Stables GI, Forsyth A, Lever RS. Patch testing in children. Contact Dermatitis 1996;34:341-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Katsarou A, Koufou V, Armenaka M, Kalogeromitros D, Papanayotou G, Vareltzidis A. Patch tests in children: a review of 14 years experience. Contact Dermatitis 1996;34:70-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Sevila A, Romaguera C, Vilaplana J, Botella R. Contact dermatitis in children. Contact Dermatitis 1994;30:292-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Ayala F, Balato N, Lembo G, Patruno C, Tosti A, Schena D, et al. A multicentre study of contact sensitization in children. Contact Dermatitis 1992;26:307-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Manzini BM, Ferdani G, Simonetti V, Donini M, Seidenari S. Contact sensitization in children. Pediatr Dermatol 1998;15:12-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Brasch J, Geier J. Patch test results in school children. Results from the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK) and the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group (DKG). Contact Dermatitis 1997;37:286-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Shah M, Lewis FM, Gawkrodger DJ. Patch testing in children and adolescents: five years' experience and follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37:964-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Fisher AA. Allergic contact dermatitis in early infancy. Cutis 1994;54:300-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Seidenari S,Giusti F, Pepe P, Mantovani L. Contact sensitization in 1094 children undergoing patch testing over a 7-year period. Pediatr Dermatol 2005;22:1-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Jacob SE, Burk CJ, Connelly EA. Patch Testing: Another steroid-sparing agent to consider in children. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:81-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Jacob SE, Brod B, Crawford GH. Clinically relevant patch test reactions in children - A United States based study. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:520-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Bruckner AL, Weston WL, Morelli JG. Does sensitization to contact allergens begin in infancy? Pediatrics 2000;105:e3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Wohrl S, Hemmer W, Focke M, Gφtz M, Jarisch R. Patch testing in children, adults, and the elderly: influence of age and sex on sensitization patterns. Pediatr Dermatol 2003;20:119-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Ferna΄ndez Vozmediano JM, Armario Hita JC. Allergic contact dermatitis in children. Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005;19:42-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Heine G, Schnuch A, Uter W, Worm M. Frequency of contact allergy in German children and adolescents patch tested between 1995 and 2002: results from the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology and the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Contact Dermatitis 2004;51:111-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Lewis VJ, Statham BN, Chowdhury MM. Allergic contact dermatitis in 191 consecutively patch tested children. Contact Dermatitis 2004;51:155-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Mortz C, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis 1999;41:121-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Weston WL, Weston JA, Kinoshita J, Kloepfer S, Carreon L, Toth S, et al. Prevalence of positive epicutaneous tests among infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics 1986;78:1070-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Barros MA, Baptista A, Correia TM, Azevedo F. Patch testing in children: a study of 562 school children. Contact Dermatitis 1991;25:156-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, Andersen KE. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and hand and contact dermatitis in adolescents: the Odense Adolescence Cohort Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:523-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Clayton TH, Wilkinson SM, Rawcliffe C, Pollock B, Clark SM. Allergic contact dermatitis in children: should pattern of dermatitis determine referral ? A retrospective study of 500 children tested between 1995 and 2004 in one UK centre. Br J Dermatol 2006;154:114-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Romaguera C, Vilaplana J. Contact dermatitis in children: 6 years experience (1992-97). Contact Dermatitis 1998;39:277-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Jacob SE, Steele T, Brod B, Crawford GH. Dispelling the Myths Behind Pediatric Patch Testing-Experience from Our Tertiary Care Patch Testing Centers. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:296-300.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Johnke H, Norberg LA, Vach W, Bindslev-Jensen C, Hψst A, Andersen KE. Reactivity to patch tests with nickel sulfate and fragrance mix in infants. Contact Dermatitis 2004;51:141-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Storrs FJ. Patch testing children-what should we change? Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:420-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Zug KA, Mc Ginley-Smith D, Warshaw EM, Taylor JS, Rietschel RL, Maibach HI, et al. Contact allergy in children referred for patch testing: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, data 2001-2004. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:1329-36.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Roul S, Ducombs G, Taieb A. Usefulness of the European standard series for patch testing in children. A 3-year single-centre study of 337 patients. Contact Dermatitis 1999;40:232-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Cronin E. Contact dermatitis. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1980. p. 20-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Rudzki E, Rebandel P. Contact dermatitis in children. Contact Dermatitis 1996;34:66-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Kuiters GR, Smitt JH, Cohen EB, Bos JD. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and young adults. Arch Dermatol 1989;30:1531-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Flora B, Oranje AP. Patch tests in children with suspected allergic contact dermatitis: A prospective study and review of the literature. Dermatology 2009;218:119-25.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

White IR. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Harper J, Oranje A, Prose N, editors. Textbook of pediatric dermatology. 2 nd ed. Blackwell publishing; 2006. p. 349-56

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Tiwari RR. Child labour in footwear industry. Indian J Occup Environ Med 2005;9:7-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Sarkar R, Kanwar AJ. Atopic Dermatitis. Indian Pediatr 2002;39:922-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Akhavan A, Cohen SR. The relationship between atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol 2003;21:158-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Krupa Shankar DS, Chakravarthi M. Atopic patch testing. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:467-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Brar KJ, Shenoi, Balachandran C, Mehta VR. Clinical profile of forefoot eczema: A study of 42 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2005;71:179-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Rietscher RC, Fowler JF. Fisher's contact dermatitis 6 th ed. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc; 2008. p. 38-43.

th ed. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc; 2008. p. 38-43. '>[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Roul S, Ducombs G, Leaute-Labreze C, Taοeb A. 'Lucy luke' contact dermatitis to the rubber components of diapers. Contact Dermatitis 1998;38:363-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Yan AC, Wahrman JE, Honig PJ. Clinical features and differential diagnosis of Napkin dermatitis. In: Harper J, Oranje A, Prose N, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology. 2 nd ed. Blackwell Publishing; 2006. p. 163.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

7,317

PDF downloads

2,213