Translate this page into:

Peeling skin syndrome in eight cases of four different families from India and Bangladesh

2 Department of Pathology, NRS Medical College, 138 AJC Bose Road, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Correspondence Address:

Nilendu Sarma

P.N. Colony, Sapuipara, Bally, Howrah - 711 227, WB

India

| How to cite this article: Sarma N, Boler AK, Bhanja DC. Peeling skin syndrome in eight cases of four different families from India and Bangladesh. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:625-631 |

Abstract

Peeling skin syndrome (PSS) is a rare recessively inherited ichthyosiform genodermatoses characterized by superficial skin peeling. This has 2 subtypes, acral (APSS; OMIM 609796) and generalized form (OMIM 270300). The later has been subdivided into type A (non-inflammatory) and type B (inflammatory). Eight cases of peeling skin syndrome in 4 families were recorded over a period of 5 years. They were diagnosed clinically and confirmed histopathologically. Disease onset ranged from birth to childhood age (mean 5.25 ± 4.528 years) and age at presentation ranged from 7-35 years (mean 23.25 ± 10.471 years). Males outnumbered females (M:F - 5:3). All had non-inflammatory generalized disease of type-A PSS variety, except one who had type-B PSS. Two Muslim families (1 st and 2 nd family, total 5 patients) came from nearby country Bangladesh, and the 2 Hindu families were Indian. Higher severity over acral areas in generalized type, possible autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and improvement with age as found in this series were new manifestations and possibly unreported previously. The disease was found to be poorly responsive to oral retinoids. Prevalence of the disease may be higher than expected. Importance of mutational analysis was also highlighted.Introduction

Peeling skin syndrome (PSS) or peeling skin disease (PSD) is a rare, recessively inherited ichthyosiform genodermatoses characterized by peeling of superficial skin. This condition was first described as a case report in 1921 by Fox who used the term ′keratolysis exfoliativa congenita.′ [1] Subsequently, many other terminologies were used to describe similar conditions like ′deciduous skin′ (Bechet), [2] ′familial continual skin peeling′ (Kurban and Azar), [3] and ′continual skin peeling syndrome′ (Silverman et al). [4]

Clinically, PSS appears as ichthyosiform dermatosis with easy skin fragility that manifests as superficial skin peeling following minimal sliding forces. Severity is variable. Based on extent of involvement, this condition has been divided into acral PSS (APSS; OMIM 609796) and generalized PSS (OMIM 270300). Acral PSS was first described by Shwayder et al. [5] Generalized variety have been further subdivided on the basis of presence of signs of inflammation like erythema into 2 subtypes - type A (non-inflammatory) and type B (inflammatory). [6] Disease localized exclusively over face has been reported in a family. [7] Mevorah et al introduced a new subtype and described it as type C. [8] This subtype starts in infancy and is characterized by atopy, itching, and presence of circular erythematous patches that are encircled by areas of peeling.

In this series, 8 cases of peeling skin syndrome from 4 different families from India and Bangladesh are reported.

Case Report

Total 8 cases in 5 families were found (male - 3, female - 5). Age of onset varied from birth to early childhood (Mean 5.25 ± 4.528 years). Age at presentation ranged from 7-35 years (23.25 ± 10.471 years). Two families

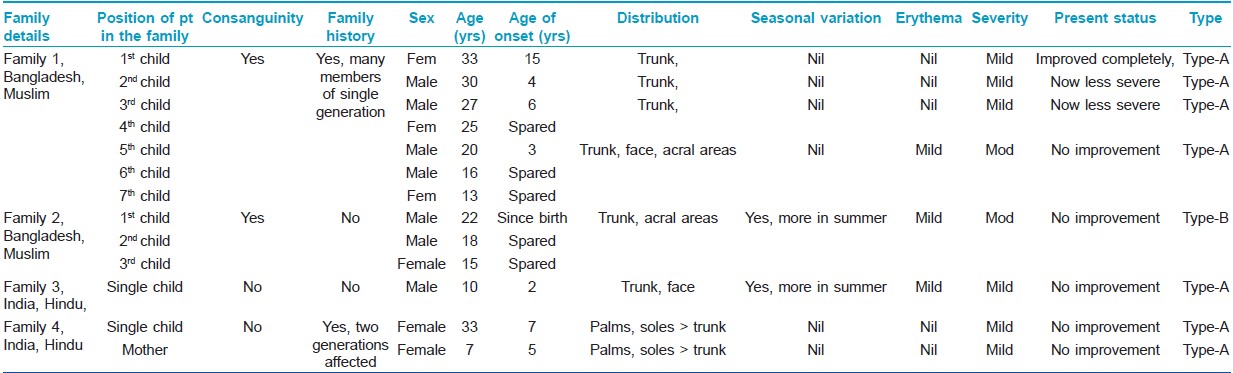

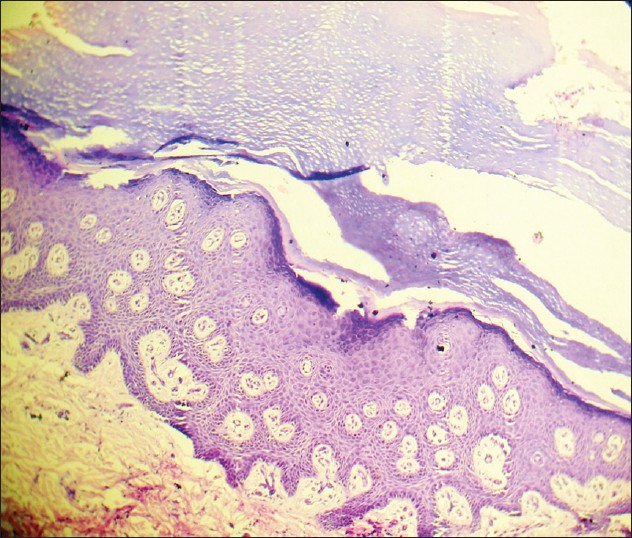

(1 st and 2 nd family, 5 patients) came from nearby country Bangladesh. All those who were Muslims had a history of consanguinity in their parents. Three cases (3 rd and 4 th family) were of Indian origin and all were Hindus without any history of consanguinity [Table - 1].

Demographic and disease details of the patients and their families have been mentioned in the [Table - 1] and some of these features were compared with 2 previous case series [Table - 2].

All cases were of non-inflammatory generalized variety (PSS-A), except one (2 nd family) who had prominent inflammatory changes (PSS-B).

Involvement of other family members with same disease was found in 2 families (1 st and 4 th family). In the 1 st family (Muslim, consanguineous), PSS-A was present among 4 out of 7 siblings in one generation. There was no evidence of disease in the previous or subsequent generations. In the 4 th family (Hindu, non-consanguineous), mother and daughter had PSS-A, but acral areas had higher severity than trunks. Partial or complete improvement in disease severity was reported by some members of the 1 st family [Table - 1]. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee.

Details of each family are mentioned below:

First family

In this Muslim family from Bangladesh, 4 siblings out of total 7 were found to be affected. There was consanguineous marriage among their parents. Only one generation was found to be affected. The disease in this family was diagnosed as type A- PSS.

The eldest daughter (33 years) developed mild and localized truncal disease at the age of 10-12 years and improved completely after few years. She had no disease activity at the time of presentation.

The 2 nd and 3 rd sons developed the disease at around 8 years of age. In both of them, the disease improved greatly in subsequent years as mentioned by them. During examination, disease was detected only over the back and chest in both of them.

Most severely affected was the 5 th son. Disease started to develop at around 3 years of age. He had extensive, asymptomatic, non-inflammatory peeling [Figure - 1]a. Minor sliding force induced peeling. Almost all areas including face were affected. Palms and soles were thickened without any fissuring.

|

| Figure 1: (a) Extensive peeling that developed following slight sliding force on trunk in a Muslim boy aged 10 years (1st family, 5th patient). (b, c) The young Hindu boy showed presence of superficial peeling over sides of cheek (3rd family). (d) Persistent superficial peeling of acral areas since early childhood in the Hindu mother (4th family) |

After routine investigations, systemic retinoid (isotretinoin) was advised only to the 5 th patient for 3 months at the dose of 20 mg/day. It failed to show any satisfactory improvement.

Second family

One 22-years-old male born from a consanguineous marriage in this Muslim family from Bangladesh presented with skin peeling. None of his family members including his two other siblings were found to be affected.

Disease started as reddish morbilliform/ miliaria-like rash just after birth. Disease showed a temporary improvement during first 2 years but progressively worsened thereafter. Palmo-plantar hyperkeratosis appeared few years later and progressed rapidly. At presentation, he had persistent erythematous thick hyperkeratosis of hands and feet with transgradiens over dorsal surfaces. There was generalized easy skin peeling and prominent erythroderma [Figure - 2]. Peeling occurred throughout the year, but severity increased noticeably during summer, after sweating or after contact with water for some duration. It was associated with bad body odor. Overall, skin appeared dry and ichthyotic. The patient was diagnosed as having type B-PSS.

|

| Figure 2: Thick keratoderma with transgradiens over hands (a) and feet (b) along with prominent erythema (2nd family, 1st patient). Lower leg showed diffuse erythema and skin peeling. Area over back of the same patient showed erythroderma and superficial peeling after mild rubbing (c) |

Oral acitretin (25 mg/ day) was given continuously for 2 months when it was stopped due to elevated liver enzyme. Only mild temporary improvement was noted.

Third family

This Indian non-consanguineous Hindu family had only one affected member who was a 10-year-old single male child. Disease started around 2 years of age and involved trunk, limbs, and face [Figure - 1]b,c. Palms and soles were spared. Disease severity was higher in summer. There was no erythema or other signs of inflammation. It was classified as type A- PSS.

He was treated with acitretin (25 mg/ day) for 3 weeks and then 10 mg/day for 6 weeks, but it failed to show any benefits.

Fourth family

In this Hindu family, without any parental consanguinity, mother (age 35 years) and her only daughter (7 years) presented with peeling of thin skin, mostly from acral areas along with mild involvement of back. [Figure - 1]d. No other family members were known to be affected.

The disease started around 5 years of age in both of them. Palmar skin showed persistent peeling throughout the year, but truncal areas had recurrent peeling during summer. The disease was asymptomatic and there was no erythema or bulla. It was diagnosed as type A- PSS. These patients could not be treated as they were lost early to follow-up.

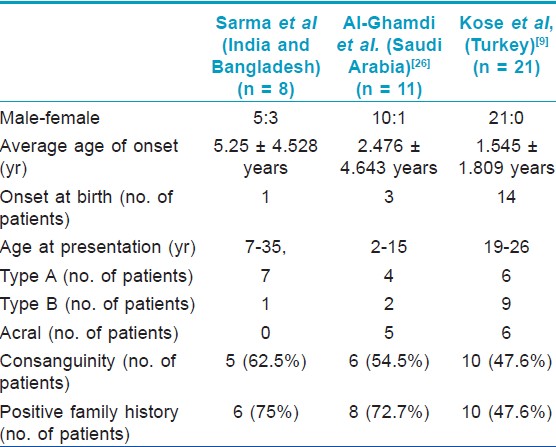

Pedigree diagrams of 1 st and 2 nd family have been depicted in [Figure - 3]. None of the patients had any hair, nail, and dental abnormality. Systemic examination did not reveal any abnormality in any of the patients. Routine systemic investigations like complete hemogram, liver function and kidney function tests, thyroid profile were normal in all. Any further metabolic and biochemical profile evaluation was not attempted in any of them.

|

| Figure 3: Pedigree diagram of 1st and 2nd family |

Histology was done from the affected areas in one member from 1 st 3 families (1 st family - 5 th child, 2 nd family - 1 st child, 3 rd family - Single affected child).[Table - 2].

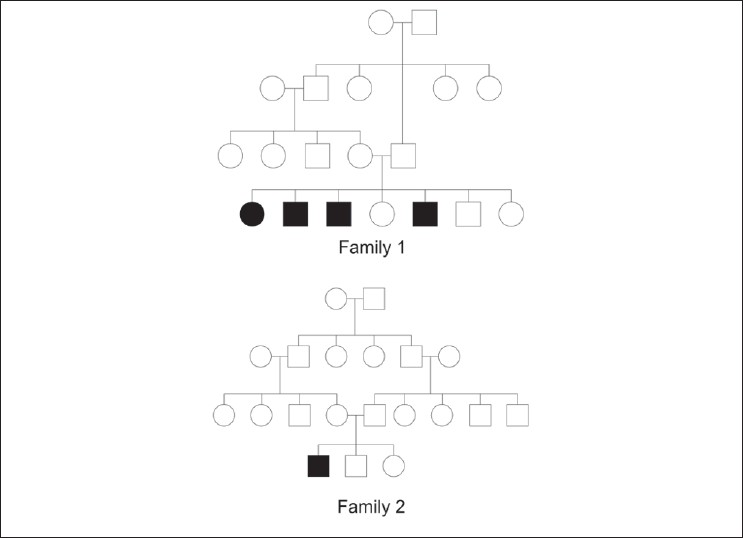

Histology in cases of type A-PSS revealed presence of orthokeratosis and intra-corneal cleft of lower part of stratum corneum in patients. In patient with type B-PSS, prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis and distinct sub-corneal split was detected [Figure - 4].

|

| Figure 4: Photomicrograph (H and E stain, ×400) showing histology of skin from back in patient with type B PSS (2nd family- 1st child) demonstrated hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and sub-corneal split |

Discussion

Diagnosis of PSS is often delayed due to late presentation in less severe and asymptomatic cases. For same reasons, misdiagnosis is also frequent. These factors might contribute to the apparent rarity of this condition. Many cases in the current series were diagnosed in adulthood despite a childhood onset. The patients in 4 th family presented only when two successive generations developed the same problem. With this report, prevalence of the disease in this part of the globe appeared to be higher than predicted from previous isolated case reports.

PSS has clinical resemblance to subcorneal pustular dermatosis, epidermolysis bullosa simplex superficialis, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, Netherton syndrome, pemphigus foliaceus, erythrokeratoderma like erythrokeratolysis hiemalis (Oudtshoorn disease), keratolysis exfoliativa and even exfoliation following dyshidrosis. [9] However, differentiation from most of these diseases can be done with almost certainty only on clinical ground supported by histological findings. Netherton′s syndrome is characterized by presence of atopy, trichorrhexis invaginata (′′bamboo hairs′′) and is caused by SPINK5 (MIM 605010) mutations, [10] which is different from the known mutations of PSS. Epidermolysis bullosa superficialis is characterized by presence of bulla, dominant mode of transmission, absence of spontaneous peeling, and onset before 2 years. [11]

Histological features are characteristic in PSS. Type-A shows orthohyperkeratosis while type B shows a psoriasiform pattern. Separation within keratinocyte at the junction of stratum granulosum and stratum corneum (Levy and Goldsmith, 1982) [12] , (Brusasco et al, 1998) [13] is considered unique and can differentiate PSS from all forms of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) where the separation is at the level of basal keratinocyte (EB simplex type), dermo-epidermal junction (junctional EB), and superficial dermis (dystrophic EB). Although EBS superficialis has similar level of cleavage or separation in the epidermis, they can be distinguished clinically. In this series, patients with non-inflammatory generalized disease (type A) showed presence of orthokeratosis and intra-corneal cleft at lower part of stratum corneum. Patient with type B PSS had prominent hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and sub-corneal split. These findings corroborated with classical findings and were helpful in confirmation of the diagnosis.

Rare associations have been reported with fragile hair and koilonychia, distal onycholysis, chapping, keratoderma, sexual dysfunction, anosmia, short stature, primary amenorrhea, poor development of sexual characters, cheilitis, keratosis pilaris, melanonychia, clubbing and hyperhidrosis. [9] Abnormal biochemical parameters like altered tryptophan levels, aminoaciduria, [14] high serum copper level, higher IgE and higher ceruloplasmin, iron and iron-binding capacity, and abnormal epidermal retinoid metabolism are also reported. [15] As mentioned, extensive investigations to detect any rare biochemical alterations were not done in this study.

PSS is known to have an autosomal recessive transmission. New mutations involving profilaggrin/filaggrin gene causing poor aggregation and disruption of keratin is also reported to cause PSS. [16] Ultrastructural studies have detected abnormal and cribriform keratohyalin granules, reduced desmosomal plates, intracellular cleavage, and intercellular electrondense globular deposits in the stratum corneum. [6],[4],[16] For acral PSS (APSS), the genetic defect has been mapped to the 10.2-Mb region on chromosome 15 (at 15q15.2) [17] that contains transglutaminase (TGM) gene cluster (containing TGM5, TGM7, and EPB42). TGM5 is expressed in the skin between granular layer and the stratum corneum and this gene is now known to play the key pathogenic role in APSS. TGMs are extremely important in terminal differentiation of the epidermis where it assists in cross-linking of keratins and structural proteins like involucrin, loricrin, filaggrin, and forms the cornified cell envelope [18] through formation of gammaglutamyl- lysine isodipeptide bonds between adjacent polypeptides. [19],[20] The mutation in PSS-B involves corneodesmosin (CDSN) gene as found in two different studies. [21],[22] Corneodesmosome maintains the structural integrity of stratum corneum. For PSS-A, the affected genes are yet to be found out. In this series, no mutation analysis was performed because of infrastructural limitation. Evaluation of clinico-histological parameters appeared to be sufficient enough to confirm the diagnosis in all cases.

There has been a male preponderance in all the reports including the current one. However, we have found a lesser gap in sex ratio [Table - 1].

In addition to presenting the case series on this rare disease, this present report highlighted few important yet previously unreported aspects of the disease.

Permanent improvement with age (many members of 1 st family) or temporary improvement for some years in the very early stage before a progressive course as seen in the patient with type B PSS (1 st patient, second family) is hitherto unreported.

Acral disease is known to be rarer, categorized as a separate entity, has specific mutation and develop without any involvement of other non-acral areas. [5],[23] On the contrary, acral involvement can be sometimes present in generalized type where the severity in acral areas is generally milder than non-acral areas. [24] One of the cases in this present series with generalized disease of type-A pattern had higher severity in acral areas than in trunk. This pattern was neither reported previously nor can be explained with currently available knowledge.

So far, only autosomal recessive mode of transmission was known for PSS. However, this cannot explain the involvement of mother and her daughter (4 th family, Hindu). Possibility of autosomal dominant mode of transmission cannot be ruled out. Unfortunately, these particular patients were lost early to follow-up even before histological evaluation or genetic confirmation could be attempted.

Retinoids failed to show any significant benefit in any of the cases this series. This supported the previous observations where methotrexate, retinoids, and steroids were found to be ineffective. [25]

Only two case series are published so far in the world literature; one from Saudi Arabia [26] and one from Turkey. [9] In 2011, Kose published the so far largest case series of 21 cases from Turkey. [9]

Some isolated cases of PSS has been reported from India. [10],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35] Total number of cases reported so far is 81 and it consisted of 20 cases of type A PSS, 27 cases of type B PSS, 2 cases of type C PSS, 21 cases of acral PSS, and 11 of undefined phenotypes. In 2010, two separate groups published single case report and reviewed the literature in the same issue of one journal. [25],[27] Kharfi et al in their review of world literature found 51 cases till then, including their own single case of type A PSS. [25] Garg et al[27] authored a single case report and reviewed the Indian literature. The present series of 8 patients of PSS is the first case series from south-east Asian countries.

| 1. |

Fox H. Skin shedding (keratolysis exfoliativa congenita): Report of a case. Arch Dermatol 1921;3:202.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Bechet PE. Deciduous skin. Arch Dermatol 1938;37:267-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Kurban AK, Azar HA. Familial continual skin peeling. Br J Dermatol 1969;81:191-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Silverman AK, Ellis CN, Beals TF, Woo TY. Continual skin peeling syndrome: An electron microscopic study. Arch Dermatol 1986;122:71-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Shwayder T, Conn S, Lowe L. Acral peeling skin syndrome. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:535-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Traupe H. The ichthyoses: A guide to clinical diagnosis, genetic counselling and therapy. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Janjua SA, Hussain I, Khachemoune A. Facial peeling skin syndrome: A case report and brief review. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:287-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Mevorah B, Frenk E, Saurat JH, Siegenthaler G. Peeling skin syndrome: A clinical, ultrastructural and biochemical study. Br J Dermatol 1987;116:117-25.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Köse O, Safali M, Koç E, Arca E, Açikgöz G, Özmen Ý et al . Peeling skin diseases: 21 cases from Turkey and a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:844-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Chavanas S, Bodemer C, Rochat A, Hamel-Teillac D, Ali M, Irvine AD, et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nat Genet 2000;25:141-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Fine J-D, Johnson L, Wright T. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex superficialis. A new variant of epidermolysis bullosa characterized by subcorneal skin cleavage mimicking peeling skin syndrome. Arch Dermatol 1989;125:633-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Levy SB, Goldsmith LA. The peeling skin syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982;7:606-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Brusasco A, Veraldi S, Tadini G, Caputo R. Localized peeling skin syndrome: Case report with ultrastructural study. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:492-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Inamdar AC, Palit A. Peeling Skin Syndrome with Aminoaciduria. Pediatr Dermatol 2005;22:314-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Mevorah B, Salomon D, Siegenthaler G, Hohl D, Meier ML, Saurat JH, et al. Ichthyosiform dermatosis with superficial blister formation and peeling: Evidence for a desmosomal anomaly and altered epidermal vitamin A metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:379-85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Cassidy AJ, van Steensel MA, Steijlen PM, van Geel M, van der Velden J, Morley SM, et al. A homozygous missense mutation in TGM5 abolishes epidermal transglutaminase 5 activity and causes acral peeling skin syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2005;77:909-17.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Kalinin AE, Kajava AV, Steinert PM. Epithelial barrier function: Assembly and structural features of the cornified cell envelope. Bioessays 2002;24:789-800.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G. The cornified envelope: A model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005;6:328-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Eckert RL, Sturniolo MT, Broome AM, Ruse M, Rorke EA. Transglutaminase function in epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 2005;124:481-92.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Oji V, Ecki KM, Aufenvenne K, Nätebus M, Tarinski T, Ackermann K, et al. Loss of the corneodesmosin leads to severe skin barrier defect, pruritus, and atopy: Unraveling the peeling skin disease. Am J Hum Genet 2010;87:274-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Israeli S, Zamir H, Sarig O, Bergman R, Sprecher E. Inflammatory peeling skin syndrome caused by a mutation in CDSN encoding corneodesmosin. J Invest Dermatol 2011;131:779-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Tolat SN, Gharpuray MB. Skin peeling syndrome. Cutis 1994;53:255-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Hashimoto K, Hamzavi I, Tanaka K, Shwayder T. Acral peeling skin syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:1112-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Aras N, Sutman K, Tastan HB, Baykal K, Can C. Peeling skin syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:135-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Kharfi M, Khaled A, Ammar D, Ezzine N, El Fekih N, Fazaa B, et al. Generalized peeling skin syndrome: Case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J 2010;16:1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Al-Ghamdi F, Al-Raddadi A, Satti M. Peeling skin syndrome: 11 cases from Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 2006;26:352-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Garg K, Singh D, Mishra D. Peeling skin syndrome: Current status. Dermatol Online J 2010;16:10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Mathur KD, Bhargava P, Singh P, Agarwal US, Bhargava RK. Continual skin peeling syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1996;62:114-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Panja SK, Sengupta S. Idiopathic deciduous skin. Int J Dermatol 1982;21:262-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Pavithran K, Ashrof MP. Keratolysis exfoliative congenitum. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1989;55:382-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Gharpuray BM, Mutalik S. Skin peeling syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1994;60:170-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Bandyopadhyay P, Chowdhury SN. Peeling skin syndrome. Ind J Dermatol 1997:42:95-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Sentamilselvi G, Thiagarajan K, Kamalam A, Murugusundaram S, Thambiah AS. Peeling skin syndrome. Indian J Dermatol 1997;42:93-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Sharma R, Kumar A. Skin Peeling Syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2000;66:154-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Mukhopadhyay AK. Peeling skin syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2004;70:115-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

10,895

PDF downloads

3,553