Translate this page into:

Photodermatoses in India

Correspondence Address:

C S Sekar

Department of Dermatology, PSG Hospitals, Peelamedu, Coimbatore - 641 004, Tamil Nadu

India

| How to cite this article: Srinivas C R, Sekar C S, Jayashree R. Photodermatoses in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:1-8 |

Abstract

Photodermatoses are a group of disorders resulting from abnormal cutaneous reactions to solar radiation. They include idiopathic photosensitive disorders, drug or chemical induced photosensitivity reactions, DNA repair-deficiency photodermatoses and photoaggravated dermatoses. The pathophysiology differs in these disorders but photoprotection is the most integral part of their management. Photoprotection includes wearing photoprotective clothing, applying broad spectrum sunscreens and avoiding photosensitizing drugs and chemicals.Introduction

Light is essential for the survival of all living things as various metabolic, endocrine, and physiological processes are dependent on exposure to sunlight. The effect of sun on skin is now a major concern among the medical fraternity and general public, particularly in the Indian scenario where exposure to sunlight is high.

Solar Spectrum and its Effects on Skin

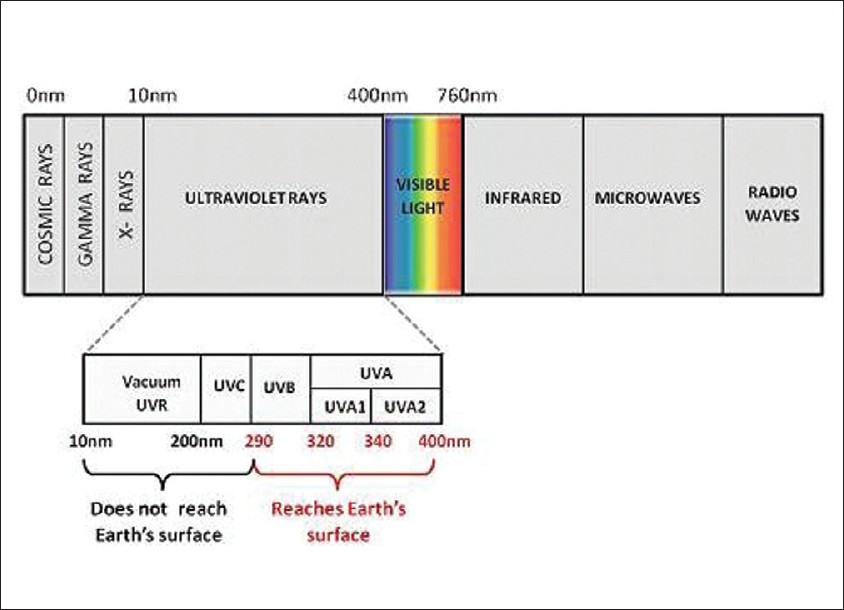

Sun is the chief component of solar system which produces a continuous spectrum of electromagnetic radiation ranging from the most energetic cosmic, gamma rays and X-rays with shorter wavelengths (<10 nm) to UVR (10-400 nm), visible light (400-760 nm), and infrared rays (760-1700 nm) [Figure - 1].

|

| Figure 1: Electromagnetic spectrum of sun |

Photo trauma is primarily the result of UVR which has four components: Vacuum UVR (10-200 nm), UVC (200-290 nm), UVB (290-320 nm), and UVA (320-400 nm). All the UVC and much of UVB are absorbed by oxygen and ozone in the earth′s atmosphere and 95% of UV radiation which reaches the earth′s surface is UVA. Moreover, the intensity of UVR is altered by environmental influences like latitude, altitude, season, time of the day, surface reflection, and atmospheric pollution.

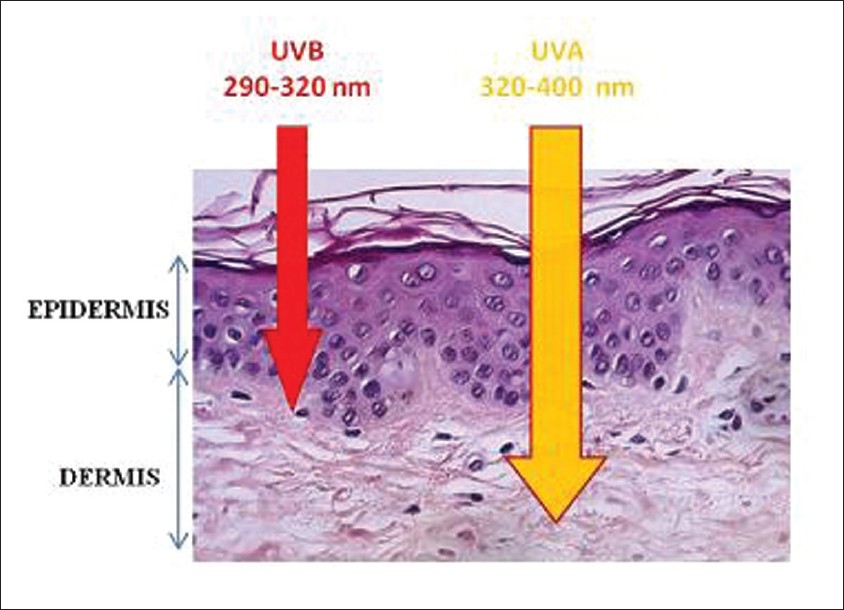

Within the skin, the depth of penetration of UV light is wavelength dependant [1],[2] (i.e. longer the wavelength, deeper the penetration) [Figure - 2]. But the biological effects of UVR are more pronounced with light of shorter wavelength as it contains high quantum of energy.

|

| Figure 2: The depth of penetration of UVR |

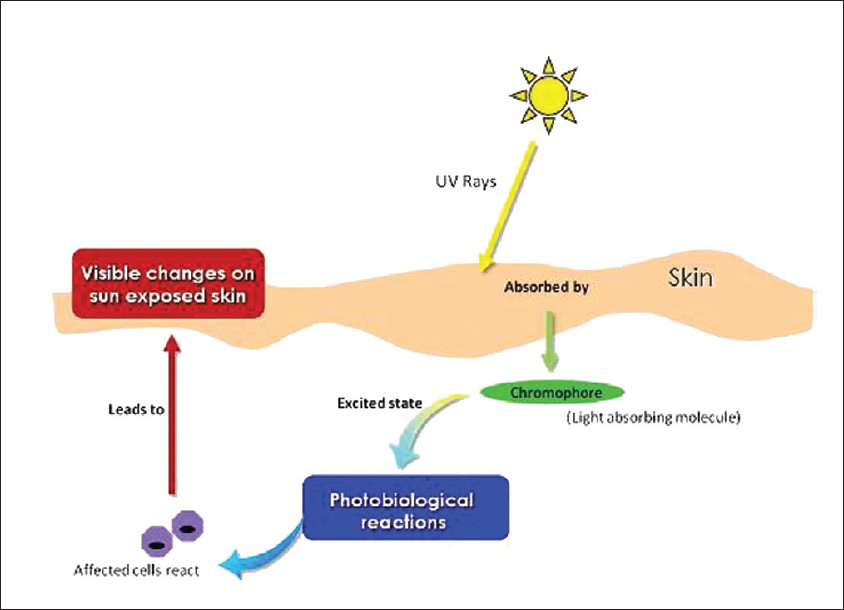

Photodermatoses encompasses a group of disorders wherein there is an abnormal tissue response to UV light, which could be due to either normal or abnormal molecular absorption leading to visible changes on sun-exposed skin [Figure - 3].

|

| Figure 3: Schematic representation of photobiological response of skin |

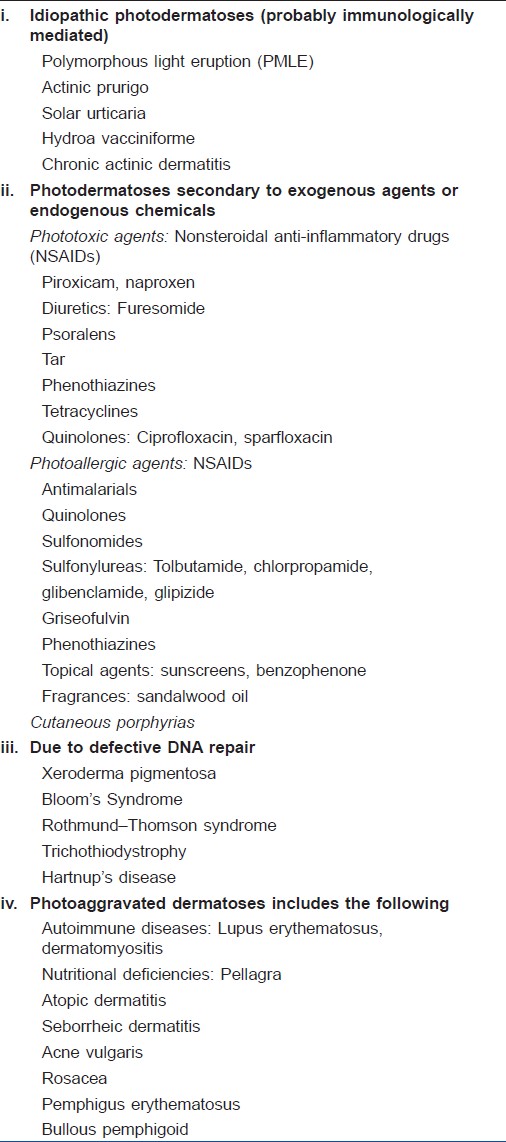

Photodermatoses can be broadly classified into four groups [Table - 1]. Out of these, polymorphic light eruption (PMLE), Parthenium dermatitis with photoaggravation, inadvertent use of photosensitizing drugs and chemicals leading to various phototoxic and photoallergic reactions, and nutritional deficiencies like pellagra are of major concern in the Indian setting.

Polymorphic Light Eruptions

Is the most common endogenous photodermatosis [3] which affects men and women of all ages. Women in their second and third decades are slightly more affected than men. It commonly occurs in fair-skinned individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types I-IV. In an Indian study conducted by Sharma and Basnet., 96% of patients were of skin types IV-VI, out of which 62.73% were females, most of them being housewives. [4]

Pathogenesis

The cause of PMLE is not known, although an immunologic basis has been demonstrated. [5]

There appears to be a delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) response to undefined endogenous, cutaneous photoinduced antigens as a result of inherited abnormality in the reduction of normal UVR-induced immunosuppression, thereby resulting in enhanced response to photoantigens and development of clinical lesions. [6]

The action spectrum is unclear, although it is most commonly 290-365 [7] and rarely visible light. Photo-provocation studies have shown positive response to broad-band UVA (50%), narrow-band UVB (50%), and to both UVA and UVB (80%). [8]

Clinical features

PMLE manifests as pruritus, erythema, macules, papules, or vesicles on sun-exposed skin arising 1-2 days after exposure and resolving spontaneously over the next 7-10 days. It is most common with initial sun exposures during spring or early summer; "hardening" of the skin may occur with subsequent exposures. Various morphological variants like the micropapular, lichen nitidus like and lichen planus like lesions have been reported. [9] As the name suggests, the lesions are polymorphic, but individual patients tend to develop the same type each year. However, lesions with varied morphology may be present in the same patient.

Treatment

The treatment consists of avoidance of sun exposure, use of protective clothing, and regular application of broad-spectrum sunscreens, Psoralen UltraViolet A and Narrow Band -Ultra Violet B. Sharma and Basnet in their study observed that irrespective of the type of clothing or weave, the covered areas were unaffected which suggests that any type of protective clothing can prevent PMLE. [4],[10] Since UV light is present throughout the day, UV protection should be advised throughout the day from switch-off to switch-on time (from the time light is switched off in the morning to the time it is switched on in the evening). However; sunscreens cannot be used in all cases as they are expensive and have to be used regularly, in adequate quantity and frequently. The exact amount of sunscreen required is 2 mg/cm 2 . This information is not of practical use to the patient. We conducted a simple study using a string to measure the circumference of the face; the study was conducted on 10 male and 10 female volunteers. The area of the face was measured by placing a wet thread along the outer margin of the face. The length of the thread was measured in centimeters. We assumed that the circumference of the face would be nearly equal to the circumference of the thread, if arranged as a circle. The radius and the area of the circle were calculated by dividing the circumference by 2p. The area of the face was then calculated by using the formula pr 2 . Since 2 mg/cm 2 is the recommended dose of sunscreen for topical application and 2 mg/cm 2 is equal to 2 μl/cm 2 , the area of the face was multiplied by 2 to determine the amount of sunscreen in microliters, which was then converted to milliliters. The mean circumference of the face of 10 male volunteers was 100 cm and of 10 female volunteers was 81 cm. The mean radius was determined as 15.9 cm for males and 12.98 cm for females. Based on the circumference and radius, the area of the face was 793.82 cm 2 for males and 530.6 cm 2 for females. Since 2 μl/cm 2 is the quantity of sunscreen required (2 × 793.82 = 1588 ml), approximately 1.6 ml of sunscreen will be needed for males, and for females, 2 × 530.6 = 1062 ml, i.e. approximately 1 ml will be needed.

The steps that are involved in the calculation are outlined for easy understanding:

Circumference (C) = 100 cm = 2πr. Radius (r) = circumference/2π 100/(2 × 22/7) = 100 × (7/2 × 22) = 15.9 cm.

Area = πr 2 = 22/7 × 15.9 × 15.9 = 3.14 × 252.81 = 793.82 = 794 cm 2 .

We were then able to recommend the amount of sunscreen needed based on the circumference of the face which is equal to the length of the string [11] [Figure - 4]. Controlled exposure to sunlight or artificial UV light sources decreases the sensitivity and increases the tolerance of human skin to UV radiation. This phenomenon is called hardening. Hardening may be accomplished with either UVA (340-400 nm) or UVA and UVB (300-400 nm), followed by exposure to midday sunlight for 15-20 minutes weekly to maintain the hardened state. Artificial hardening induced by narrowband TL-01 UVB is more effective than that induced by PUVA, which is more effective than broadband UVB. [12] The starting dose is 70% of the minimal erythema dose or minimal phototoxic dose for UVB and PUVA, respectively, followed by a 10-20% increment per treatment. An average of two to three weekly sessions over a period of 5 weeks is usually sufficient to induce hardening. [12]

|

| Figure 4: Face lined with a thread |

However, hardening is unpredictable. We have noticed polymorphic light eruption occurring during early summer and improving later on without intervention. This would suggest that natural hardening does occur in many patients. Hence, in mild cases of PMLE, which is very common in India, promotion of natural hardening will suffice. From our personal experience, we have noticed that natural hardening occurs during regular walks if undertaken during early part of the day after sunrise or before sunset when the weather is pleasant and UV rays predominate.

Other treatment modalities include the following.

Antimalarials: Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily for the first month and 200 mg once daily for the next month would be a cheap and effective alternative for sunscreens and phototherapy. Moreover, antimalarials need to be used only during the summer months; therefore, the total necessary dose is small and can be used safely in the dosage studied in such patients with little risk of ocular toxicity. [13]

Beta-carotene in the dose of 3 mg/kg body weight is effective for prophylactic treatment of PMLE. Topical steroids and a brief course of systemic corticosteroids may be recommended for symptomatic patients. Cyclosporine or azathioprine may be used for severe cases. Topical calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D) and its analogues such as calcipotriol have been shown to exhibit immunosuppressive properties and can be used as a prophylactic in patients with PMLE. [14]

Chronic Actinic Dermatitis (CAD)

This is a rare chronic photodermatosis of sun-exposed and, to a lesser extent, covered skin. [15],[16]

Pathogenesis

The cause of CAD very likely seems to be a DTH reaction against an endogenous, cutaneous, photo-induced allergen, leading to precisely the same picture as allergic contact dermatitis.

Clinical features

It is characterized by pruritic papules and plaques with lichenification, particularly on the exposed skin of the face, scalp, back, sides of the neck, upper chest, and the dorsal surfaces of the arms and backs of the hands. Islands of exposed skin sometimes may be unaffected, but large areas of covered skin instead may be affected. Infiltration of the skin leads to an accentuation of skin markings on the face and a rare tendency to leonine facies in severe cases. Sparing in the depth of skin creases, skin folds, finger webs, and upper eyelids may occur. Eczematous changes of palms and soles are usual. Hair, especially of eyebrows and eyelashes, may be short and stubby or lost, presumably from scratching, while large areas of marked hyper- or hypopigmentation variably occur on exposed or covered areas. Erythroderma develops in severe cases. The condition is worse in summer and after sun exposure, although this relationship is not always noticed by patients.

In India, patients with CAD exhibit contact sensitivity to a range of contact allergens, especially to Parthenium hysterophorus, a weed of Compositae family, and to a lesser extent to phosphorus sesquisulfide, colophony, rubber, metals, and allergens used in medicaments, perfumes, and sunscreens. [17],[18] Photocontact dermatitis secondary to P. hysterophorus too has been reported. [19] This is probably due to its profuse and widespread growth and its high sensitizing property. However, its photosensitizing potential remains debatable. While Sharma et al.[20] could correlate P. hysterophorus causing photocontact allergy, Srinivas and Shenoi.[21] did not observe any photosensitivity. However, Kar et al. in their study have noted that Parthenium plays an important role in the initiation and perpetuation of airborne contact dermatitis (ABCD) and CAD. [22] Similarly, Somani has also reported photoallergy to Parthenium. [18] Thus, these agents and particularly the oleoresins from Compositae plants might play a role in inducing the photoaggravation of CAD. The photoaggravation in Parthenium dermatitis [23],[24] might possibly be due to some unrecognized allergens of Parthenium or to some other additional allergens unrelated to Parthenium, but the exact mechanism for this remains to be elucidated. [25] Hence, the chronic eczematous skin in CAD enables easier penetration of oleoresins and other airborne allergens and leads to a secondary and incidental contact dermatitis, thereby tending to exacerbate and not to cause the disease.

Diagnosis is based on clinical features. Parthenium dermatitis may present as lichenoid eruptions in sun-exposed areas. This clinical variant needs to be recognized to avoid misdiagnosis. [26] Phototests reveal a reduction in 24-h erythema and exaggerated papular responses to UVB, UVA, and rarely, visible wavelengths. Patch tests are necessary to rule out airborne contact dermatitis as a cause of CAD if light sensitivity is not present and to reveal contact sensitizers, particularly to sunscreen constituents, which may be exacerbating the CAD.

Treatment consists of strict photoprotection and avoidance of contact allergens if any. Short course of topical steroids with emollients and systemic steroids is effective during flares.

In refractory cases, azathioprine (1-2.5 mg/kg/day) or pulse therapy in the dose of 300 mg/week, [27],[28] cyclosporine (3.5-5 mg/kg/day), mycophenolate mofetil (25-50 mg/kg/day), low-dose PUVA, and topical tacrolimus can be used in various combinations. [29]

Solar Urticaria

This is a rare immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated photodermatosis [30],[31] characterized by transient cutaneous eruption of wheals evoked by exposure to UVR or visible light.

Pathogenesis

Degranulation of mast cells occurs as in other forms of urticaria, but the exact mechanism triggering the process is not known. Existence of a circulating serum factor induced by an action spectrum and mediated through antibody production (probably IgE) [32] that causes subsequent histamine release has been hypothecated. The action spectra responsible for eliciting urticarial lesions are generally specific and consistent for a given patient. Most studies cite action spectra between 300 and 500 nm (visible: 380-700 nm; UVA: 320-400 nm; UVB: 280-320 nm), [33] but there have also been reports of infrared-induced urticaria. [34] The differences in action spectra could be due to heterogeneous nature of chromophores or photosensitizers, and ethnic and geographic differences may also play a role. [35]

Clinical features

Patients present with a tingling sensation over the exposed areas within 5-10 minutes of sun exposure, followed rapidly by erythema and wheals. The wheals commonly become confluent with a well-defined ridge of skin at the margin of the exposed sites. Habitually exposed areas, such as the face and the backs of the hands, may not be affected. The eruption settles completely within 1 or 2 h of cessation of exposure. It occurs commonly in the fourth or fifth decade of life with a female preponderance. Solar urticaria is divided into two types: type I and type II. [30] Type I defines patients who have precursors located in the serum, plasma, or cutaneous tissue fluid, which become photoallergens once activated by the appropriate wavelength and bind to IgE receptors, resulting in mast cell degranulation. Type II is also IgE mediated, but precursors are found in both healthy patients and patients with solar urticaria. It is hypothesized that only patients with solar urticaria have an abnormal circulating IgE autoantibody that recognizes these irradiated precursors. [31]

Treatment consists of sun protection with high sun protection factor (SPF) absorbent sunscreens and restriction of UVB exposure, low-dose UVA, PUVA, and antihistamines. The effect of antihistamines in the treatment of solar urticaria is unpredictable. As cutaneous blood vessels contain both H1 and H2 receptors, a combination of H1 and H2 receptor antagonist would be efficacious. By objective phototesting using a solar simulator, the efficacy of antihistamine combination in suppressing the urticarial response has been demonstrated. [36]

Phototoxic and PhotoAllergic Reactions

In India, where there are no strict regulations for over the counter drugs, drug reactions have become very common. The lack of advice regarding the avoidance of sunlight and inappropriate dosing can lead to various drug-induced phototoxic reactions.

Phototoxic reactions are nonallergic cutaneous responses induced by a variety of topical and systemic agents. The common drugs which cause phototoxic reaction are:

- Antimicrobials: Quinolones, tetracyclines, sulfonamides,

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), Retinoids, and Furocoumarins.

Pathophysiology

The absorbtion of radiation by photosensitizer results in oxygen-dependant photodynamic process leading to the formation of free radicals causing cytotoxic injury. [37]

Clinical features

The symptoms are similar to sunburn and include acute dermatitis with reddening, edema, vesicles, or blisters, and subsequently resulting in severe pigmentation. Tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones can induce phototoxic distal onycholysis. [38] Phototoxic reactions after amiodarone and chlorpromazine therapy are accompanied by slate-gray, usually irreversible pigmentation. [39] Pseudoporphyria like reaction can occur secondary to naproxen, cyclosporine, and β-lactam antibiotics. [40]

Treatment

Identification and avoidance of the phototoxic agent are the primary steps in the management of phototoxic reactions. Acute reaction can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Sun avoidance with broad-spectrum sunscreen should be used to prevent reactions.

Photoallergic Reaction

Photoallergic reaction is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction requiring a photoallergic substance which gets activated with UV radiation, particularly UVA range.

Apart from NSAIDs and antimicrobials like quinolones and sulfonamides, various topical agents have been implicated in photoallergic reactions, as follows:

- Sunscreens: Benzophenones, para amino benzoic acid (PABA) derivatives, cinnamates

- Fragrances: Musk ambrette, sandalwood oil.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenetic mechanisms of photoallergic reactions are quite similar to those of allergic dermatitis. The photoantigen (hapten) is presented by epidermal Langerhans cells to T lymphocytes, resulting in delayed skin hypersensitivity response characterized by lymphocytic infiltration, release of lymphokines, activation of mast cells, and increased cytokine expression. [41]

Clinical features

Patients present with a pruritic eczematous reaction 24-48 h after exposure to the sensitizing agent. This reaction presents as an eczematous eruption with erythema, papules, and vesicles, pruritis, oozing and crusting, and later, scaling and lichenification.

Management

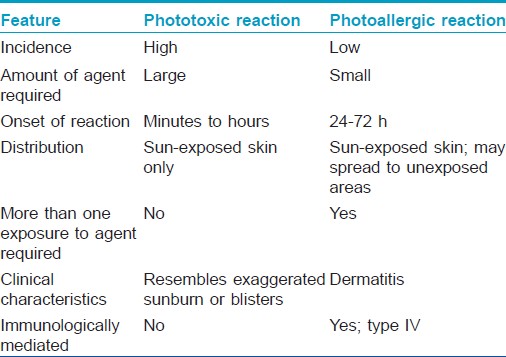

The management of photoallergic reaction is similar to that of phototoxic reaction, with sunscreens and topical steroids being the mainstay of treatment. If the lesions are severe, a course of systemic steroids is warranted. The recovery is often slower than from a phototoxic reaction [Table - 2].

Nutritional Dermatoses - Pellagra

Pellagra is a nutritional disease caused by the deficiency of niacin characterized by photodistributed rash, gastrointestinal symptoms, and neuropsychiatric disturbances. It was first described in 1762 by Gaspar Casal as "mal de la rosa," and was later renamed as pellagra in Italy, from "pelle agra," meaning rough skin. [42],[43]

Causes

Apart from nutritional deficiency, chronic alcoholism, drugs, and carcinoid syndrome can cause pellagra.

Pathophysiology

Niacin can be obtained directly from diet or is synthesized from tryptophan. Dietary niacin is mainly in the form of nicotinamide adenine nucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phospate (NADPH). These molecules undergo hydrolysis in the intestinal lumen to form nicotinamide, which can be converted to nicotinic acid by intestinal bacteria or absorbed directly into the bloodstream. [44] Nicotinamide and nicotinic acid are then reincorporated as a component of coenzymes NAD and NADP, which in turn intervene in essential oxidation-reduction reactions. Tissues with high energy requirements, such as the brain, or high turnover rates, such as gut or skin, are primarily affected. [45] The exquisite photosensivity seen in pellagra may result from a deficiency of urocanic acid and/or cutaneous accumulation of kynurenic acid, which may induce a phototoxic reaction.

Clinical features

The skin eruption is characteristically a photosensitive rash affecting the dorsal surfaces of the hands, face, neck, arms, and feet. In the acute phase, it resembles sunburn with erythema and bullae (wet pellagra), but progresses to a chronic, symmetric, scaly rash that exacerbates following re-exposure to sunlight. The Casal necklace extends as a fairly broad band or collar around the entire neck (cervical dermatome with C3 and C4 innervation). The other characteristic features are diarrhea and progressive dementia.

Management

The treatment of pellagra is with oral nicotinamide supplementation, 100-300 mg daily in 3-4 separate doses, until resolution of the major acute symptoms occurs. The dosage can then be reduced to 50 mg every 8-12 h until the skin lesions heal. Resolution of dermatitis occurs in 3-4 weeks.

Rare Conditions

Porphyrias

Porphyrias are a group of inherited or acquired disorders of certain enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway. Cutaneous porphyrias include porphyria cutanea tarda, erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP), hepatoerythropoietic porphyria, variegate porphyria, and congenital erythropoietic porphyria. In all cutaneous porphyrias except EPP, cutaneous photosensitivity manifests as fragile skin and bullous eruptions. Skin changes generally occur on sun-exposed areas (e.g. face, neck, dorsal sides of fingers and hands) or traumatized skin. The cutaneous reaction is insidious, and often patients are unaware of the connection to sun exposure. In contrast, the photosensitivity in EPP occurs within minutes or hours after sun exposure, manifesting as a burning pain that persists for hours, often without any objective signs on the skin. The exact incidence of porphyria in India is unknown, but there are few case reports in the Indian literature. Kumar et al.[46] reported congenital erythropoietic porphyria associated with ventricular septal defect. Koley and Saoji.[47] have reported two cases of congenital erythropoietic porphyria. Ghosh et al.[48] have reported a case of porphyria cutaneous tarda.

Hartnup′s disease

Hartnup′s disease is a rare autosomal recessive inborn error of neutral amino acid transport, characterized by the abnormal membrane transport of the essential amino acid, tryptophan, which results in a secondary niacin deficiency causing pellagra-like manifestations, both cutaneous and neuropsychiatric. Amladi and Kohli.[49] and Patel and Prabhu.[50] have reported a case of Hartnup′s disease in India.

Xeroderma pigmentosum

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by photosensitivity, pigmentary changes, premature skin aging, and malignant tumor development due to cellular hypersensitivity to ultraviolet radiation resulting from a defect in DNA repair. Its incidence in the Indian context is not significant. Rao et al.[51] have reported a case of XP in India.

Other disorders such as atopic eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, and rosacea can aggravate on exposure to sunlight.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is characterized by photosensitivity, malar rash, and discoid lupus erythematosus like skin lesions which can be aggravated in tropical climate.

Conclusion

In India, the incidence of photodermatoses is common in view of the tropical weather, lack of knowledge regarding sun protection, and inadvertent consumption of phototoxic drugs. Identification of the cause and avoidance of triggering factors will help in reducing the incidence of photodermatoses.

| 1. |

Anderson RR, Parrish JA. The optics of human skin. J Invest Dermatol 1981;77:13-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Bruls WA, Slaper H, Van der Leun JC, Beurrens L. Transmission of human epidermis and stratum corneum as a function of thickness in the ultraviolet and visible wavelengths. Photochem Photobiol 1984;40:485-94.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Hanigsmann H. Polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2008;24:155-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Sharma L, Basnet A. A clinic epidemiological study of polymorphic light eruption. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:15-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Millard TP, Bataille V, Snieder H, Spector TD, McGregor JM. The heritability of polymorphic light eruption. J Invest Dermatol 2000;115:467-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Palmer RA, Friedmann PS. Ultraviolet radiation causes less immunosuppression in patients with polymorphic light eruption than in controls. J Invest Dermatol 2004;122:291-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Friedlander J, Lowe NJ. Exposure to radiation from the sun. In: Auerbach PS, editors. Wilderness Medicine: Management of Wilderness and Environmental emergencies. 3 rd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1995.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Das S, Lloyd JJ, Walshaw D, Farr PM. Provocation testing in polymorphic light eruption using fluorescent ultraviolet (UV) A and UVB lamps. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:1066-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Bhutani LK. The photodermatoses as seen in tropical countries. Semin Dermatol 1982;1:175-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Jansen CT. The natural history of polymorphous light eruptions. Arch Dermatol 1979;115:165-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Srinivas CR, Lal S, Thirumoorthy M, Sundaram SV, Karthick PS. Sunscreen application: Not less, not more. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:306-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Man I, Dawe RS, Ferguson J. Artificial hardening for polymorphic light eruption: Practical points from ten years experience. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 1999;15:96-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Pareek A. Comparative study of efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in polymorphic light eruption: A randomized, double-blind, multicentric study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:18-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Gruber-Wackernagel A, Bambach I, Legat FJ, Hofer A, Byrne SN, Quehenberger F, et al. Randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled intra-individual trial on topical treatment with a 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D 3 analogue in polymorphic light eruption. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:152-63.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Menage H, du P, Hawk JL. The idiopathic photodermatoses: Chronic actinic dermatitis (photosensitivity dermatitis/actinic reticuloid syndrome). In: Hawk JL, editor. Photodermatology. London: Arnold; 1999. p. 127-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Lim HW, Morison W, Kamide R, Buchness MR, Harris R, Soter NA. Chronic actinic dermatitis: An analysis of 51 patients evaluated in the United States and Japan. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:1284-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Menage H, Ross JS, Norris PG, Hawk JL, White IR. Contact and photocontact sensitization in chronic actinic dermatitis: Sesquiterpene lactone mix is an important allergen. Br J Dermatol 1995;132:543-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Somani VK. Chronic actinic dermatitis-A study of clinical features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2005;71:409-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Bhutani LK, Rao DS. Photocontact dermatitis caused by Parthenium hysterophorous. Dermatologica 1978;157:206-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Sharma VK, Sethuraman G, Bansal A. Evaluation of photopatch test series in India. Contact Dermatitis 2007;56:168-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Srinivas CR, Shenoi DS. Minimal erythema dose to ultra-violet light in parthenium dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1994;60:149-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Kar HK, Langar S, Arora TC, Sharma P, Raina A, Bhardwaj M. Occurrence of plant sensitivity among patients of photodermatoses: A control-matched study of 156 cases from New Delhi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2009;75:483-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Jeanmougin M, Taieb M, Mancieb JR, Moulin JP, Ciratte J. Photo-aggravated Parthenium hysterophorus contact eczema. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1988;115:1238-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Lakshmi C, Srinivas CR. Parthenium: A wide angle view. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:296-306.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Jindal N, Sharma NL, Mahajan VK, Shanker V, Tegta GR, Verma GK. Evaluation of photopatch test allergens for Indian patients of photodermatitis: Preliminary results. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:148-55.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Verma KK, Sirka CS, Ramam M, Sharma V K. Parthenium dermatitis presenting as photosensitive lichenoid eruption. A new clinical variant. Contact Dermatitis 2002;46:286-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Srinivas CR, Balachandran C, Shenoi SD, Acharya S. Azathioprine in the treatment of parthenium dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1991;124:394-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Verma KK, Bansal A, Sethuraman G. Parthenium dermatitis treated with azathioprine weekly pulse doses . Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:24-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Nousari HC, Anhalt GJ, Morison WL. Mycophenolate in psoralen-UV-A desensitization therapy for chronic actinic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 1999;135:1128-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Botto NC, Warshaw EM. Solar urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:909-20.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Waibel KH, Reese DA, Hamilton RG, Devillez RL. Partial improvement of solar urticaria after omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:490-1.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Sams WM Jr. Solar urticaria: Studies of the active serum factor. J Allergy 1970;45:295-301.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Roelandts R, Ryckaert S. Solar urticaria: The annoying photodermatosis. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:411-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Mekkes JR. Solar urticaria induced by infrared radiation. Clin Exp Dermatol 2003;28:222-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Horio T. Solar urticaria-idiopathic? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2003;19:147-54.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Srinivas CR, Fergusson J, Shenoi SD, Pai S. Solar urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1995;61:288-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Babilas P, Landthaler M, Szeimies RM. Photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Eur J Dermatol 2006;16:340-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Baran R, Juhlin L. Photoonycholysis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2002;18:202-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Angel TA, Stalkup JR, Hsu S. Photodistributed blue-gray pigmentation of the skin associated with long-term imipramine use. Int J Dermatol 2002;41:327-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

LaDuca JR, Bouman PH, Gaspari AA. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-induced pseudoporphyria: A case series. J Cutan Med Surg 2002;6:320-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Vassileva SG, Mateev G, Parish LC. Antimicrobial photosensitive reactions. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1993-2000.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Karthikeyan K, Thappa DM. Pellagra and skin. Int J Dermatol 2002;41:476-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Williams AC, Ramsden DB. Pellagra: A clue as to why energy failure causes diseases? Med Hypotheses 2007;69:618-28.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Nogueria A, Duarte AF, Magna S, Azevedo F. Pellagra associated with esophageal carcinoma and alcoholism. Dermatol Online J 2009;15:8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Jen M, Shah KN, Yan AC. Cutaneous changes in nutritional disease. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffel DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. USA: McGraw Hill; 2008. p. 1209-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Kumar P, Manimegalai M, Amudha S, Premalatha S. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria associated with ventricular septal defect. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1999;65:189-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Koley S, Saoji V. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria: Two case reports. Indian J Dermatol 2011;56:94-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Chatterjee G, Ghosh AP. Porphyria cutanea tarda. J Assoc Physicians India 2008;56:441.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Amladi TS, Kohli M. Hartnup disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1994;60:105-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Patel AB, Prabhu AS. Hartnup disease. Indian J Dermatol 2008;53:31-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Rao TN, Bhagyalaxmi A, Ahmed K, Mohana Rao TS, Venkatachalam K. A case of melanoma in xeroderma pigmentosum. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2009;52:524-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

21,057

PDF downloads

4,396