Translate this page into:

Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in community-acquired primary pyoderma

2 Departments of Microbiology, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai, India

Correspondence Address:

Rahul Patil

Department of Dermatology, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai 400 012, Maharashtra

India

| How to cite this article: Patil R, Baveja S, Nataraj G, Khopkar U. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in community-acquired primary pyoderma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:126-128 |

Abstract

Background: Although prevalence of MRSA strains is reported to be increasing, there are no studies of their prevalence in community-acquired primary pyodermas in western India. Aims: This study aimed at determining the prevalence of MRSA infection in community-acquired primary pyodermas. Methods: Open, prospective survey carried out in a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai. Materials and Methods: Eighty-six patients with primary pyoderma, visiting the dermatology outpatient, were studied clinically and microbiologically. Sensitivity testing was done for vancomycin, sisomycin, gentamicin, framycetin, erythromycin, methicillin, cefazolin, cefuroxime, penicillin G and ciprofloxacin. Phage typing was done for MRSA positive strains. Results : The culture positivity rate was 83.7%. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in all cases except two. Barring one, all strains of Staphylococcus were sensitive to methicillin. Conclusions: Methicillin resistance is uncommon in community-acquired primary pyodermas in Mumbai. Treatment with antibacterials active against MRSA is probably unwarranted for community-acquired primary pyodermas.

Staphylococcus aureus and S treptococcus pyogenes are the common causative agents of cutaneous bacterial infections.[1] Methicillin-resistant S taphylococcus aureus (MRSA), once considered primarily as a nosocomial pathogen, is being increasingly reported from India as a colonizer in healthy individuals without risk factors and even in community-acquired infections, including pyodermas.[2],[3] The implications of these reports for the current prescription practices for cutaneous bacterial infections are obvious. It is therefore essential to determine the susceptibility pattern of clinical isolates of S. aureus in different communities across our diverse country. The present study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of MRSA in community-acquired primary pyodermas in outpatients visiting an urban tertiary care hospital.

Methods

This open prospective survey was carried out in a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai. Eighty-six consecutive patients with primary pyodermas visiting the dermatology outpatient between February and July 2004 were included. Patients with cellulitis, erysipelas, secondary pyodermas or those receiving local or systemic antibiotic therapy and those with a history of hospitalization within the last year were excluded.

Sterile swabs were used for aseptically collecting the exudate or pus from the lesions. They were then processed as per the standard protocol for the isolation of aerobic bacteria.[4] The specimens were inoculated on 5% sheep blood agar; MacConkey′s agar; and mannitol salt agar, which was used as a selective medium for S. aureus . S. aureus was identified based on Gram′s stain morphology, colony characteristics and positive catalase and coagulase tests. Antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed by the Kirby Bauer Disc Diffusion method as per National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines.[5] The antimicrobials tested included penicillin G [10 units], erythromycin [15 mg], vancomycin [30 mg], sisomycin [10 mg] , gentamicin [10 mg], framycetin [100 mg], ciprofloxacin [5 mg], cefazolin [30 mg] and cefuroxime [30 mg]. S. aureus ATCC 25923 was used as a control. Methicillin resistance was detected by using 1 mg oxacillin discs.

Results

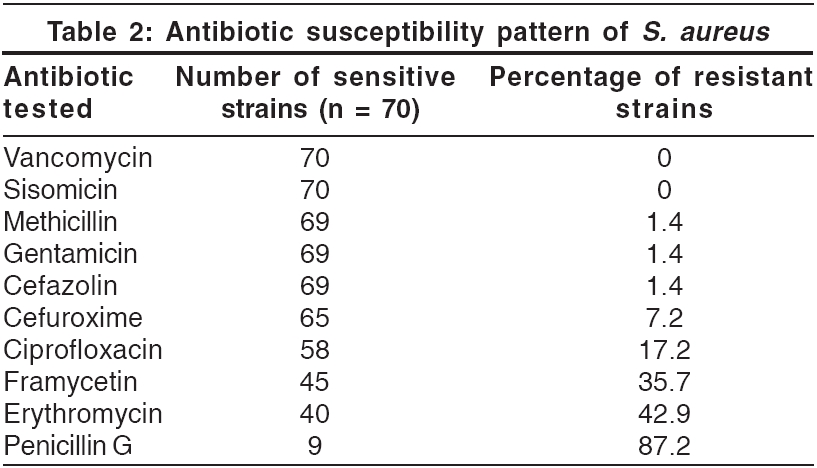

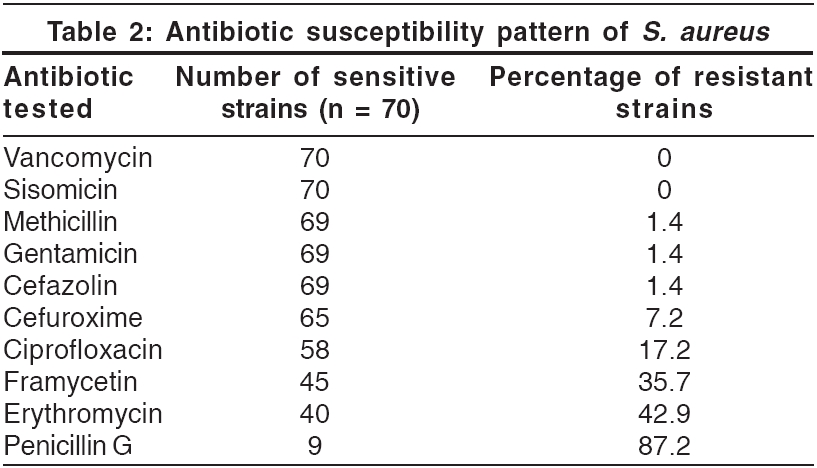

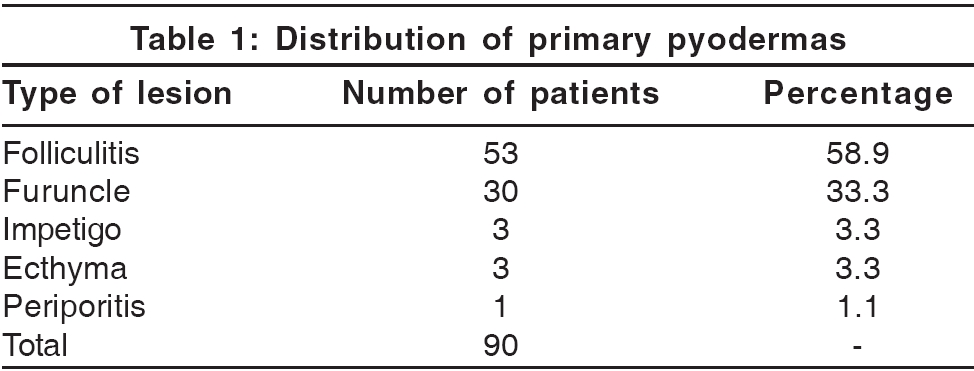

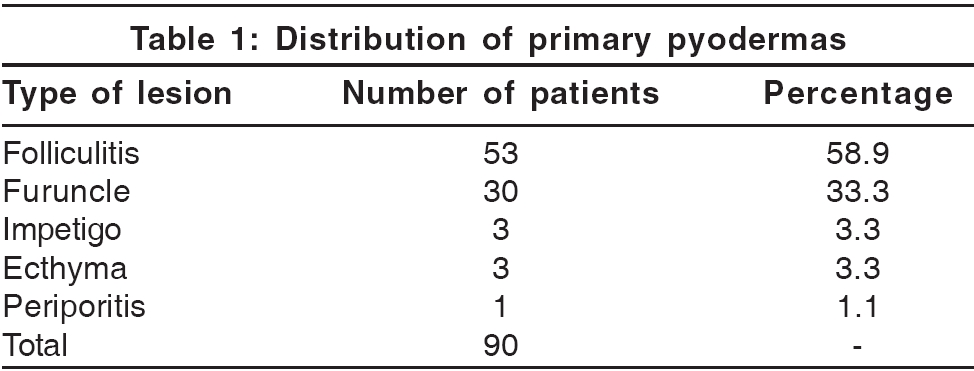

Eighty-six patients (54 males and 32 females) with community-acquired primary pyodermas were enrolled. Their ages ranged from 5 to 80 years (mean age = 36.1 years, median age = 38.5 years). Folliculitis [Table - 1] was the predominant primary pyoderma (58.8%), followed by furunculosis (33.3%).

Of the 86 swabs cultured aerobically, growth was obtained in 72, with a culture positivity rate of 83.7%. Only one organism was isolated from any sample. S. aureus was the predominant pathogen, being isolated from 70 patients (81.4%). The remaining two isolates were S. pyogenes . All the strains of S. aureus [Table - 2] were sensitive to vancomycin and sisomycin. The sensitivity to other antibiotics varied. Only one of the seventy strains of S. aureus was methicillin resistant.

Discussion

The present study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of MRSA in community-acquired primary pyodermas.

Folliculitis and furunculosis were the commonest primary pyodermas, seen in 58.8% and 33.3% of cases respectively. These have also been reported to be the most frequent primary pyodermas in some other studies,[6],[7] while in one study in children, impetigo was the commonest lesion.[8] The majority of our patients were adults, which could account for the high frequency of folliculitis and furunculosis.

All samples in our study yielded monomicrobial flora, with S. aureus isolated from 81.4% of patients and Strepto. pyogenes from 2.3%. Cultures were negative in 16.3% of the patients. Baslas et al. also reported negative cultures in 14.9% of patients.[7] S. aureus is the predominant pathogen reported in other studies as well,[3],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10] including cases of secondary pyodermas. However, since Gram negative bacilli also account for secondary pyodermas, S. aureus is relatively less frequently associated with secondary pyodermas than with primary pyodermas.[7],[10] Other studies have reported polymicrobial flora ranging from 5-16%;[8],[9] this is not surprising since only patients with primary bacterial infections were selected for our study. In another study, Strepto. pyogenes accounted for 26.98% of the total isolates.[11]

Many reports from India and Asia have highlighted the prevalence of MRSA in the community as well as in community-acquired pyodermas.[2],[3],[10],[12] In a series on community-acquired pyodermas from Mangalore, Nagaraju et al. reported that 11.8% of strains of 202 S. aureus strains were methicillin resistant.[3] According to the National Staphylococcal Phage Typing Centre, New Delhi, there is an increase in the occurrence of methicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus from 9.83% in 1992 to 45.44% in 1998.[13] MRSA strains were more common in southern India (30.94%) than in the west (20.33%) or north (18.88%). Thus, it is likely that the prevalence of methicillin resistance in community-acquired S. aureus strains also varies in different regions. In our study, only one of the seventy strains of S. aureus (1.4%) was methicillin resistant. This low prevalence was probably because our study included only community-acquired primary pyodermas as against the earlier retrospective study where samples from hospitalized and OPD patients were received from all types of infections.

In our series, the sensitivity of S. aureus strains to other antibiotics varied. All the strains were sensitive to vancomycin and sisomycin. They showed minimal resistance to first generation cephalosporins and gentamicin (1.4%). Resistance was greatest to penicillin (87.2%), followed by that to erythromycin (42.9%) and framycetin (35.7%), an antimicrobial used for topical application. Resistance to ciprofloxacin was 17.2%. In other studies too, an increasing resistance to erythromycin is being observed.[3],[13],[14]

The emergence of antibiotic resistant strains poses a significant problem both in community as well as hospital practice in deciding empiric therapy. It is therefore important to monitor the changing trends in bacterial infections and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Studies like the present one help in establishing the etiological agents and deciding empiric therapy from time to time. The increasing resistance observed to framycetin and erythromycin limits their use as first choice antimicrobial agents. In patients with primary pyodermas, cephalosporins and penicillinase resistant penicillins (e.g., methicillin, cloxacillin) can be considered as preferred first line systemic therapeutic agents. Similarly, the first choices of topical therapy for primary pyodermas are probably gentamicin and sisomicin rather than framycetin. However, we have not been able to check the sensitivity of these isolates to some other popular topical antibacterials like sodium fusidate, mupirocin and nadifloxacin as our study was focused on the frequency of MRSA strains. In spite of this drawback, our findings indicate that it may probably be unnecessary to use antibacterials useful for MRSA strains on a routine basis for the empirical treatment of community-acquired primary pyodermas. However, these findings need to be confirmed by a larger study.

| 1. |

Singh G, Kaur V, Singh S. Bacterial infections. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, editors. IADVL Textbook and atlas of dermatology. 2nd ed. Bhalani Book Depot: Mumbai; 2001. p. 190-214.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Saxena S, Singh K, Talwar V. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus prevalence in community in the east Delhi area. Jpn J Infect Dis 2003;56:54-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Nagaraju U, Bhat G, Kuruvila M, Pai GS, Jayalakshmi, Babu RP. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in community-acquired pyoderma. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:412-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Collee JG, Fraser AG, Marmuin BP, Simmons A, editors. In: Mackie and McCartney's Practical medical microbiology. 14th ed. Churchill Livingstone: New York; 1996.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS). Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard M2-A7. Wayne (PA): The Committee; 2000.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Lorette G, Beaulieu P, Bismuth R, Duru G, Guihard W, Lemaitre M, et al. Community acquired cutaneous infections - causal role of some bacteria and sensitivity to antibiotics. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2003;130:723-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Baslas RG, Arora SK, Mukhija RD, Mohan L, Singh UK. Organisms causing pyoderma and their susceptibility patterns. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1990;56:127-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Kakar N, Kumar V, Mehta G, Sharma RC, Koranne RV. Clinico-bacteriological study of pyodermas in children. J Dermatol 1999;26:288-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Lee CT, Tay L. Pyodermas: An analysis of 127 cases. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1990;19:347-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Tan HH, Tay YK, Goh CL. Bacterial skin infections at a tertiary dermatological centre. Singapore Med J 1998;39:353-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Singh G, Bhattacharya K. Bacteriology of pyodermas and antibiograms of pathogens. Indian J Dermatol 1989;34:25-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Nishijima S, Kurokawa I. Antimicrobial resistance of staphylococcus aureus isolated from skin infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2002;19:241-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Mendiratta PL, Vidhani S, Mathur MD. A study on staphylococcus aureus strains submitted to a reference laboratory. Indian J Med Res 2001;114:90-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Ohana N, Keness J, Verner E, Raz R, Rozenman D, Zuckerman F. Skin-isolated, community acquired staphylococcus aureus - in vitro resistance to methicillin and erythromycin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;21:544-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,952

PDF downloads

1,989