Translate this page into:

Primary eccrine carcinoma with polymorphous features in a 20-year-old man

Corresponding author: Dr. Chao Ji, Department of Dermatology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, Fujian, China. jichaofy@fjmu.edu.cn

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Xiao Z, Zhang J, Guo Y, Ji C. Primary eccrine carcinoma with polymorphous features in a 20-year-old man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:803-7.

Sir,

Eccrine carcinoma is an extremely rare malignant adnexal neoplasm that accounts for less than 0.01% of diagnosed skin malignancies.1 At present, only two cases have been reported in young patients in their 20s.2,3 The clinical presentation is either non-specific or is usually described as a slowly growing papule or plaque on the head or extremities. Eccrine carcinoma usually demonstrates syringoid features in histopathology. The immunohistochemical study can be helpful to exclude other cutaneous neoplasms and visceral adenocarcinomas with skin metastases. We present an unusual case of eccrine carcinoma with multiple histopathologic growth patterns in a 20-year-old male.

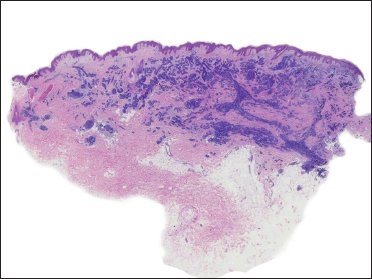

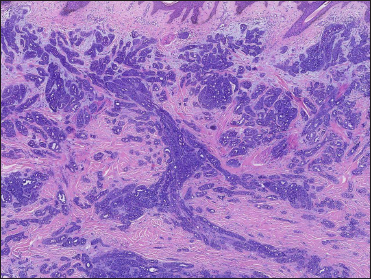

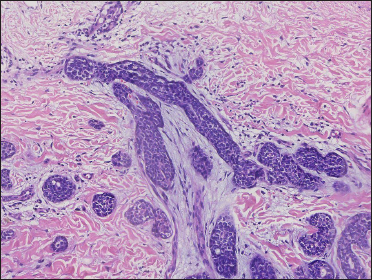

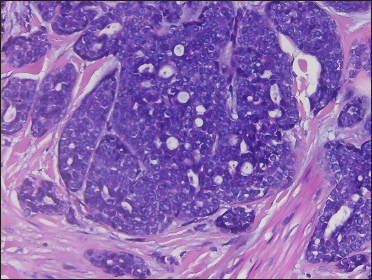

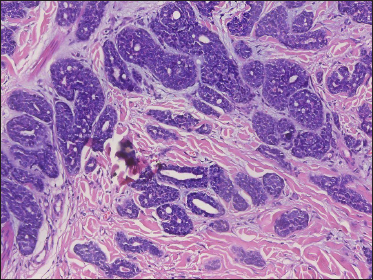

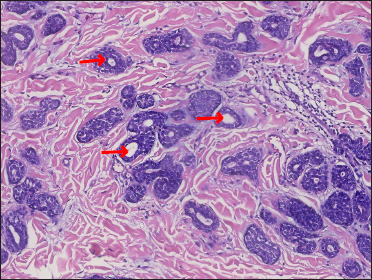

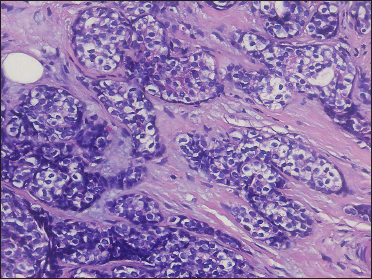

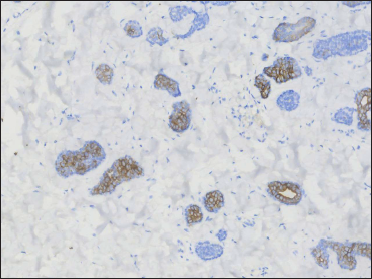

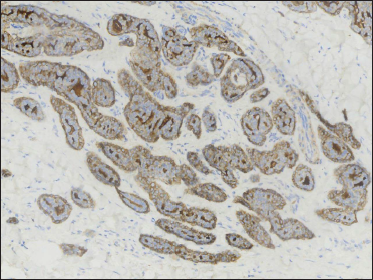

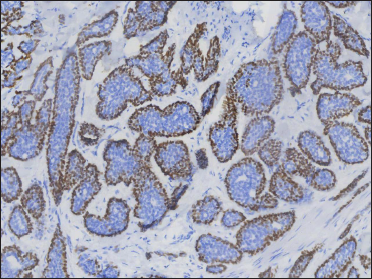

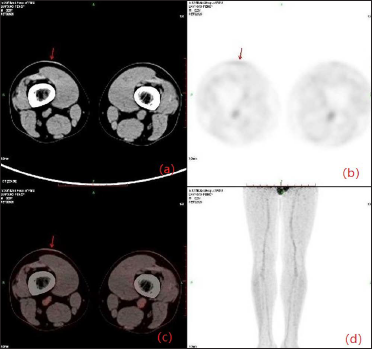

A 20-year-old Chinese male presented with a one-year history of a gradually enlarging, tender, but otherwise asymptomatic lesion on his right lower thigh. There was no history of trauma at the local site, nor family history of any malignancy. Physical examination revealed a dark, poorly circumscribed indurated plaque measuring 5 x 3 cm [Figure 1]. There was no erosion or ulceration noted. No lymphadenopathy was detected. On histopathologic examination, the sections revealed a poorly circumscribed infiltrative neoplastic proliferation throughout the dermis and extending to the subcutis [Figure 2a]. The neoplasm was in solid, tubular, and cribriform aggregations that varied in size and shape [Figures 2b–d]. In some areas, the neoplasm was forming ductal and glandular structures [Figure 2e], some appearing syringoid [Figure 2f]. The neoplastic cells were basaloid with hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm, some with clear cytoplasm [Figure 2g]. Rare atypical mitosis was present. No perineural involvement was identified. Immunohistochemical studies were performed; the neoplastic cells expressed AE1/AE3, carcinoembryonic antigen and CK7 [Figure 2h]. Epithelial membrane antigen highlighted the lining cells of the ductal structures [Figure 2i], and p63 stained the periphery of the aggregates [Figure 2j]. Ber-EP4, androgen receptors, adipophilin, CK20, CD43, CD117, S100, estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, periodic acid-Schiff staining with diastase, Alcian blue and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were negative. A positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan indicated mildly increased metabolism on the skin medial and cephalad to the right patella [Figures 3a–d]. No other skin lesion was identified. A scan of the whole body had also been done, and there was no evidence of malignancy. A diagnosis of primary eccrine carcinoma with polymorphous features was made, staged as pT3bNxMx. The lesion was excised in full-thickness and with 3 cm margins of normal skin.

- A dark, poorly circumscribed indurated plaque on the right lower thigh

- An infiltrative and poorly circumscribed neoplastic proliferation throughout the dermis and extending to the subcutis (H&E, original magnification ×20)

- Neoplasm was in solid, tubular and cribriform aggregations that varied in size and shape. (H&E, original magnification ×40)

- Neoplasm in tubular aggregations (H&E, original magnification ×200)

- Basaloid neoplastic cells in solid and cribriform aggregations (H&E, original magnification ×400)

- Neoplasm forming ductal and glandular structures with scant stroma (H&E, original magnification ×200)

- Aggregations with syringoid appearance – “syringomatous features” (red arrow) (H&E, original magnification ×200)

- Neoplastic cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and clear cytoplasm (H&E, original magnification ×400)

- Positive CK7 on tubular aggregates (original magnification ×200)

- Epithelial membrane antigen highlighting the lining cells of ductal structures (original magnification ×200)

- p63 positive at the periphery of the aggregates (original magnification ×200)

- (a) CT and (b) fusion images showing a focus to be a plaque in the right lower thigh (red arrow); (c) Transaxial PET through the right lower thigh showing a distinct hypermetabolic focus (red arrow); (d) An anterior projection PET image showing an indeterminate focus in the lower thigh skin

Eccrine carcinoma was originally described as basal cell carcinoma with eccrine differentiation. Apart from a syringomatous appearance, the present case also demonstrated other patterns, like solid, adenoid, cribriform, tubular and clear cells. Immunohistochemical staining was utilized as it is a helpful tool in the diagnosis of adnexal neoplasms, although there is a lack of specific markers for eccrine carcinoma. The neoplastic cells expressed Pan-CK, CK7, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen and p63 in the present case which was compatible with previously reported cases,4 and supported the diagnosis.

Because of the unusual histopathological presentation in the present case, the differential diagnoses includes polymorphous sweat gland carcinoma, cribriform carcinoma, sebaceous carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and metastatic adenocarcinoma. This case had overlap features with polymorphous sweat gland carcinoma, which has been reported with an admixture of morphological patterns. However, apart from solid, trabecular, tubular and adenoid cystic structures, polymorphous sweat gland carcinoma commonly reveals large solid aggregates with spiradenoma/cylindromatous features with some of the ductal structures lined by an eosinophilic cuticle. Also, unlike in this case, the polymorphous sweat gland carcinoma is positive for androgen receptors and negative for epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen in the immunohistochemical study. Cribriform carcinoma is a distinctive histopathologic variant of carcinoma with apocrine differentiation. Histopathologically, it consists of well-circumscribed dermal nodules with multiple, interconnected, solid aggregations of basophilic epithelial cells punctuated by small round spaces.5 The neoplasm displays apocrine secretion and expresses gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, which was absent in the present case. Because of the presence of clear cells, sebaceous carcinoma was also considered in the differential diagnosis. However, unlike sebaceous carcinoma, the clear cells did not have vacuolated cytoplasm or scalloped nuclei. The present case was also negative for androgen receptors and adipophilin which are expressed in sebaceous carcinoma. Adenoid cystic carcinoma presents mainly in tubular and cribriform patterns and expresses CD117 and CD43 in immunohistochemistry. In addition, there is no accumulation of mucin, thus it does not favour the diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Finally, positron emission tomography/computed tomography examination revealed negative results, and the diagnosis of primary adnexal neoplasm was further supported by the positive p63 staining.

In conclusion, dermatologists and dermatopathologists should be familiar with the histopathologic features and be aware that eccrine carcinoma has a non-specific clinical presentation, that the histopathologic features may be polymorphous, and that the lesion may occur in patients of younger age groups.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2020J02053) and the Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University (2019QH2033).

Declaration of Patient Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the family of the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interests.

References

- Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subungual syringoid eccrine carcinoma of the great toe nail complex: A case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2014;104:504-07.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primary eccrine adenocarcinoma of the skin: A single-centre experience of 10 years. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2017;97:268-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymorphous sweat gland carcinoma: An immunohistochemical and molecular study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:580-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primary cutaneous cribriform apocrine carcinoma: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases of an under-recognized cutaneous adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:644-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]