Translate this page into:

Prognosis in patients with alopecia areata with poliosis: A retrospective cohort study of 479 cases

Corresponding author: Dr. Won-Soo Lee, Department of Dermatology and Institute of Hair and Cosmetic Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Republic of Korea. leewonsoo@yonsei.ac.kr

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Lim SH, Kang H, Jung SW, Lee WS. Prognosis in patients with alopecia areata with poliosis: A retrospective cohort study of 479 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023;89:595–9.

Dear Editor,

Alopecia areata is a chronic autoimmune disease caused by autoreactive CD8+ T cells.1 During the treatment of alopecia areata, poliosis is commonly observed.2 Most former studies have reported individual cases of alopecia areata with poliosis; our previous study has reported a significant association of poliosis with hypertension, which may be attributed to insufficient vasculature of the scalp in the hypertensive state leading to poliosis.3 However, there are limited data evaluating the outcome of hair regrowth related to poliosis in the course of alopecia areata. Thus, herein, we performed an expanded retrospective analysis to evaluate and compare the outcome of hair regrowth in patients with alopecia areata with and without poliosis.

In total, 479 patients with alopecia areata who visited Wonju Severance Christian Hospital between March 2012 and December 2021 were analysed [Table 1]. Patients who presented with poliosis during follow-up and those who did not were assigned to two different groups. All assessments were performed objectively based on clinical photographs and electronic medical records by three dermatologists. All included patients had Fitzpatrick skin type III or IV.

| Clinical characteristics | Study population (n = 479) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poliosis (n = 141) | Non-poliosis (n = 338) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

| OR (95% CI) | P–value | OR (95% CI) | P–value | |||

| Age (years) | 47.7 ± 13.2 | 33.9 ± 16.2 | 1.010 (1.008–1.013) | <0.001 | 1.008 (1.005–1.011) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.138 | 0.865 | ||||

| Male | 76 (53.9%) | 157 (46.4%) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 65 (46.1%) | 181 (53.6%) | 0.940 (0.866–1.020)* | 1.008 (0.920–1.104)* | ||

| Duration of disease (months) | 34.8 ± 72.0 | 24.2 ± 48.4 | 1.001 (1.000–1.002)† | 0.067 | 1.001 (0.999–1.001)† | 0.374 |

| Initial SALT | ||||||

| Sum | 19.4 ± 1.5 | 13.2 ± 1.0 | 1.004 (1.002–1.006)‡ | <0.001 | 1.004 (1.002–1.007)‡ | 0.001 |

| Top | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 1.006 (1.002–1.011)‡ | 0.011 | ||

| Temporal | 6.6 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 1.008 (1.003–1.013)‡ | 0.004 | ||

| Back | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 1.017 (1.009–1.026)‡ | <0.001 | ||

| Comorbidities | (n = 134) | (n = 335) | ||||

| Hypertension | 19 (14.2%) | 17 (5.1%) | 1.300 (1.116–1.513) | <0.001 | 1.040 (0.875–1.236) | 0.653 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (4.5%) | 6 (1.8%) | 1.246 (0.962–1.614) | 0.096 | 0.964 (0.749–1.240) | 0.773 |

| Thyroid diseases | 4 (3.0%) | 7 (2.1%) | 1.083 (0.826–1.420) | 0.564 | 1.106 (0.832–1.470) | 0.488 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 14 (10.4%) | 12 (3.6%) | 1.307 (1.094–1.560) | 0.003 | 1.114 (0.910–1.364) | 0.296 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 3 (2.2%) | 31 (9.3%) | 0.808 (0.691–0.945) | 0.008 | 0.871 (0.743–1.021) | 0.090 |

| Obesity§, n (%) | 40 (28.4%) | 58 (17.2%) | 1.142 (1.028–1.269) | 0.014 | 1.070 (0.965–1.186) | 0.203 |

| Family history of AA | ||||||

| Overall | 20 (14.9%) | 51 (15.2%) | 0.995 (0.888–1.116) | 0.935 | 1.024 (0.913–1.149) | 0.683 |

| Parental | 7 (5.2%) | 23 (6.9%) | 0.946 (0.800–1.118) | 0.513 | ||

| Maternal | 4 (3.0%) | 16 (4.8%) | 0.914 (0.747–1.120) | 0.387 | ||

| Siblings | 11 (8.2%) | 18 (5.4%) | 1.105 (0.932–1.309) | 0.250 | ||

| Treatment modalities | ||||||

| DPCP | 46 (32.6%) | 63 (18.6%) | 1.180 (1.071–1.299) | <0.001 | 1.207 (1.010–1.442) | 0.039 |

| Superficial cryotherapy | 50 (35.5%) | 147 (43.5%) | 0.933 (0.859–1.014) | 0.104 | 1.086 (0.967–1.219) | 0.166 |

| Topical corticosteroids | 78 (55.3%) | 241 (71.3%) | 0.879 (0.806–0.959) | 0.004 | 1.021 (0.874–1.191) | 0.796 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 18 (12.8%) | 44 (13.0%) | 0.995 (0.881–1.124) | 0.941 | 1.061 (0.914–1.232) | 0.435 |

The data are presented as mean ± SD or number (percentage), *OR per year, †OR per month, ‡OR per SALT score, §Obesity is defined as body mass index ≥25 kg/m2, AA: alopecia areata, CI: confidence interval, DPCP: diphenylcyclopropenone contact immunotherapy, OR: odds ratio, SALT: severity of alopecia areata tool, SD: standard deviation

Of the 479 patients assessed, 141 (29.4%) presented with poliosis. In univariable analysis, the average age was significantly higher in the poliosis group (47.7 ± 13.2 vs 33.9 ± 16.2; P < 0.001). The initial severity of the alopecia areata tool score was significantly higher in patients with poliosis (19.4 ± 1.5 vs 13.2 ± 1.0; P < 0.001), which was consistent within all subdivisions (top, both temporal areas and back) of the scalp area. Hypertension (odds ratio, 1.300; 95% confidence interval, 1.116–1.513) and dyslipidaemia (odds ratio, 1.307; 95% confidence interval, 1.094–1.560) were significantly associated with comorbidities in the poliosis group, whereas atopic dermatitis was more prevalent in the non-poliosis group (odds ratio, 0.808; 95% confidence interval, 0.691–0.945). Patients with poliosis showed a propensity toward obesity compared with patients without poliosis (odds ratio, 1.142; 95% confidence interval, 1.028–1.269). In terms of treatment modality, diphenylcyclopropenone immunotherapy (odds ratio, 1.180; 95% confidence interval, 1.071–1.299) and topical corticosteroid treatment (odds ratio, 0.879; 95% confidence interval, 0.806–0.959) were also associated with poliosis. However, in multivariable analysis, only age (odds ratio, 1.008; 95% confidence interval, 1.005–1.011), initial severity of alopecia areata tool score (odds ratio, 1.004; 95% confidence interval, 1.002–1.007) and diphenylcyclopropenone (odds ratio, 1.207; 95% confidence interval, 1.010–1.442) were significantly associated with poliosis. The relationship between the subtypes of alopecia areata (totalis, universalis and ophiasis) and poliosis was additionally evaluated among patients whose follow-up photographs were taken; however, no significant association was revealed (P = 0.245, P = 0.788 and P = 0.999, respectively).

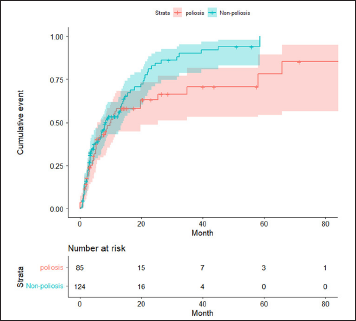

The cumulative incidence of hair regrowth (80%, assessed by the reduction in the severity of alopecia areata tool score compared to the baseline score) is shown in Figure 1. Poliosis was associated with a slightly poor prognosis, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.07). To adjust for possible confounders, a multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was performed, adjusted by age and sex. Consistently, despite the low hair regrowth rate in the poliosis group, the difference was not statistically significant (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.48–1.06; P = 0.10). The proportional hazard assumption was satisfied (P > 0.05).

- Cumulative incidence plot of 80% hair regrowth (80% reduction in the severity of alopecia areata tool score compared to the baseline score) in patients with alopecia areata with and without poliosis. Poliosis was associated with a slightly poor prognosis, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.07)

Poliosis has been recognised as indirect evidence of melanin-associated autoantigen in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata.1 In most cases, poliosis emerges early during hair regrowth and is transient.4 Active inflammation targeting melanin-associated antigens may deplete melanin and suppress pigment transfer to the hair shafts. In our study, increased age, higher initial severity of alopecia areata tool scores (severity) and diphenylcyclopropenone treatment were associated with poliosis. Immunosuppressed or immunomodulated microenvironments induced by various treatment modalities may facilitate hair regrowth. The time gap between depletion and resynthesis of the pigment on treatment may lead to grey-to-white hair regrowth. Older patients with low melanin reserves may be more vulnerable to poliosis.5

Factors associated with a poorer prognosis of alopecia areata include younger age at initial presentation, severity at onset and ophiasis subtype.1 In our study, poliosis was prevalent in patients with initially severe alopecia areata, but it was not associated with the subtypes of alopecia areata. This may be due to the small number of patients with ophiasis (n = 7).

Our study was limited by its retrospective nature, single-institution design and single-ethnicity population. Moreover, detailed information possibly related to poliosis, such as nail changes, was lacking. Skin colour could be another confounding factor because of possible differences in the melanin reservoir.

In conclusion, although there was slightly low hair regrowth in the poliosis group, no significant association was revealed between poliosis and alopecia areata prognosis. We believe that our data are valuable as they suggest an association between poliosis and prognosis of alopecia areata, for which limited information is available. Further well-controlled studies are required to confirm our findings.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alopecia areata: Disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alopecia areata with white hair regrowth: Case report and review of poliosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alopecia areata and poliosis: A retrospective analysis of 258 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1776-1778.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White hair in alopecia areata: Clinical forms and proposed physiopathological mechanisms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;S0190-9622:30010-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alopecia areata: Light and electron microscopic pathology of the regrowing white hair. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:155-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]