Translate this page into:

Quality of life in psoriasis patients in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa

2 Program of BioResearch Ethics and Medical Law, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban,

Correspondence Address:

Preetha Hariram

Department of Dermatology, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, Durban

| How to cite this article: Hariram P, Mosam A, Aboobaker J, Esterhuizen T. Quality of life in psoriasis patients in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:333-334 |

Sir,

The uses of quality of life (QOL) indices have been detailed in a previous review. [1] Developing countries lag behind in making QOL a target of holistic patient care. This is the first QOL study on psoriasis, with a correlation of clinical severity and sites of involvement, conducted in South Africa (SA). It reflects on a multiracial community of predominantly the Indian and Black population group, in Stanger, KwaZulu Natal (KZN).

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in the Dermatology Outpatient Clinic. Consenting patients underwent the following: Clinical confirmation of the type of psoriasis, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scoring, percentage body surface area (BSA) calculation by the rule of nines, site of involvement, nail changes, and assessment for psoriatic arthritis. A comprehensive demographic questionnaire was used. QOL was assessed by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and the Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI). These indices were also translated into Zulu for Black participants.

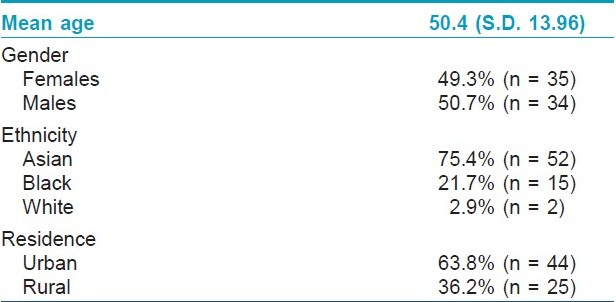

The demographic profile is illustrated in [Table - 1].

The mean PASI score of Black participants was 23.0 (S.D. 14.6), which was significantly higher than that of Indians (mean 11.4, S.D. 7.7; P < 0.001). Rural patients had a significantly higher mean for PASI, of 17.2 (S.D. 12.8), compared to urban patients with a mean of 11.9 (S.D.8.7, P = 0.045). A change in the political era since the end of apartheid, in 1994, has resulted in an increased number of primary health clinics; however, access to healthcare is still difficult for most Black rural residents. Time to seek healthcare is delayed due to financial constraints and may account for more severe disease at presentation. Furthermore, consulting with traditional healers and beliefs of bewitchment is not uncommon in our setting and contributes to late referrals, with more advanced disease presentations.

The mean PDI score was 12.2 (S.D. 7.1) and the mean DLQI was 11.1 (S.D. 5.5). At least 50.7% (n = 35) had a DLQI score between 11 and 20, which equated to a ′very large effect on the quality of life′. The greatest impairment in the PDI was in the daily activities (mean 42.4%, S.D. 22.6). There were no significant associations between the demographic variables and the QOL. Specifically, despite there being a preponderance of Indian participants (75%), there was no significant difference in QOL scores between the ethnic groups. This highlights the fact that patients′ perception of the disease transcends racial and cultural grounds. This is supported by Gelfand et al., in their study sample consisting of African Americans and Caucasians. [2]

However, the site of involvement affected the QOL. Patients with head / neck and genitalia / groin involvement had significantly higher PDI scores ( P = 0.010 and 0.028) than those without the involvement of these sites. PDI scores for hand / foot involvement were non-significantly higher than those without involvement of this site ( P = 0.057). Those with head / neck, genitalia / groin, and hand / foot involvement had significantly higher DLQI scores ( P = 0.002, P = 0.004, and P = 0.038) than those who were not affected at these sites.

The sensitive sites of head / neck, hand / foot, and genitalia / groin affect all aspects of the quality of life, including interpersonal relationships, occupation, sport, recreation, and sexuality and intimacy issues. As an example, visible lesions on the head / neck region add to the social isolation, hand involvement can deter a handshake and groin involvement can make a sexual partner suspect an infectious etiology. Although involvement of these sites, alone or in combination, may result in a low BSA or PASI score, QOL impairment may be significantly greater. A previous report has referred to these sites as emotionally charged body regions that have a significant impact on QOL. [3]

Correlations of PASI with DLQI and PDI were weak (r = 0.352 and r = 0.281, respectively), similar to a previous study. [4] In contrast, an Iranian study has shown a good correlation between these QOL indices and PASI. [5] Socioeconomic, religious, and cultural differences could account for this difference. However, both these studies have shown a good correlation between the PDI and DLQI, similar to ours (r = 0.789). [4],[5]

This South African study demonstrates that a clinician assessment alone is inadequate to assess the overall severity of psoriasis. Furthermore, certain sites are prone to greater QOL impairment. It is critical that QOL tools become an important measure of patient satisfaction and treatment monitoring in the developing world.

| 1. |

Finlay AY. Quality of life indices. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2004;70:143-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, Thomas J, Kist J, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: Results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52:23-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Wolkenstein P. Living with Psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:28-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Sampogna F, Sera F, Abeni D. Measures of Clinical Severity, Quality of Life, and Psychological Distress in Patients with Psoriasis: A Cluster Analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2004;122:602-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Aghaei S, Moradi A, Ardekani GS. Impact of psoriasis on quality of life in Iran. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2009;75:220.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,453

PDF downloads

2,505