Translate this page into:

Scedosporiosis presenting with subcutaneous nodules in an immunocompromised patient

2 Department of Dermatology and Venereology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

Correspondence Address:

Jisu Chen

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou

China

| How to cite this article: Hu H, Chen J. Scedosporiosis presenting with subcutaneous nodules in an immunocompromised patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:71-73 |

Sir,

We describe a case of scedosporiosis in a 76-year-old farmer who consulted us for painless, multiple, nodular skin lesions on the extensor surface on both his forearms for 6 months. He had had coronary heart disease for 10 years and gouty arthritis for 3 years and took prednisolone 15 mg daily for 2 years on his own. On physical examination, multiple nodular skin lesions were present on the dorsal aspect of both hands and forearms. Most of the nodules were ulcerated, with intermittent oozing of serous fluid. Some nodules had intact overlying skin, while some others were firm [Figure - 1].

|

| Figure 1: Nodules with a clear boundary of erythema. Some nodules had intact overlying skin on the extensor of forearm with some draining purulent material |

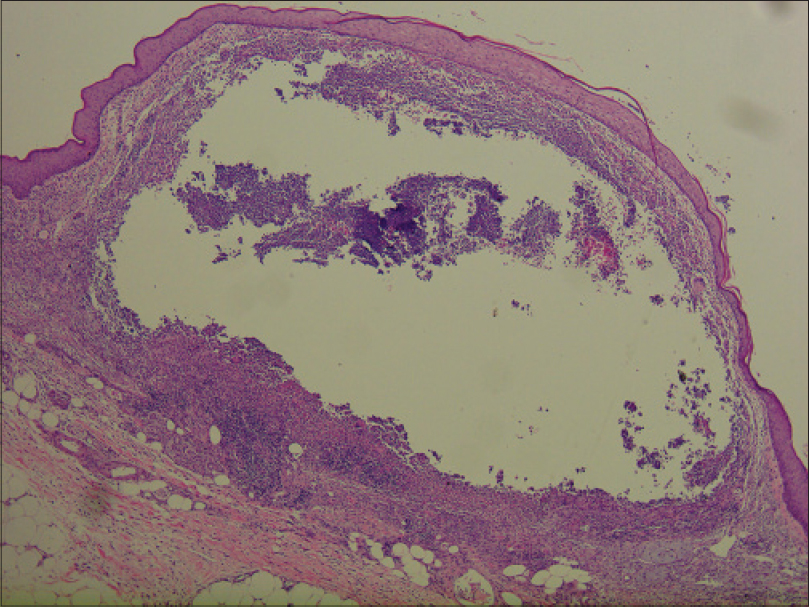

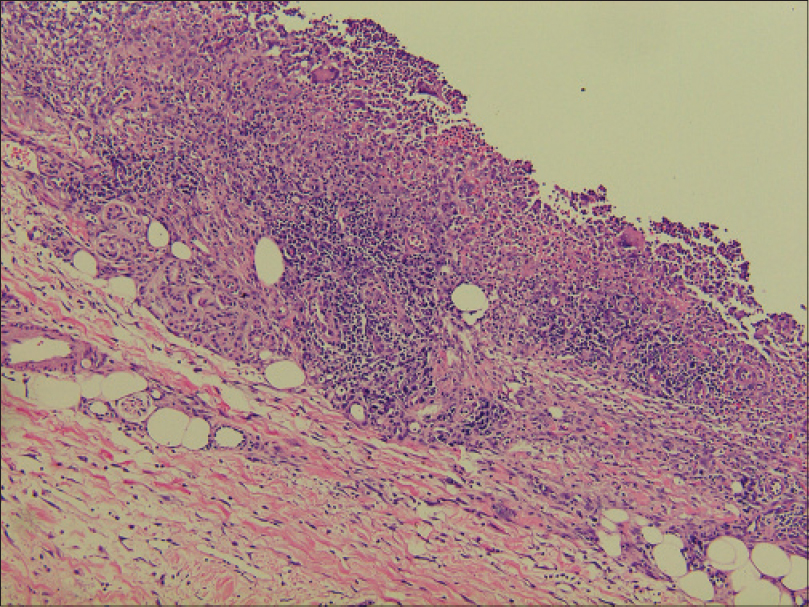

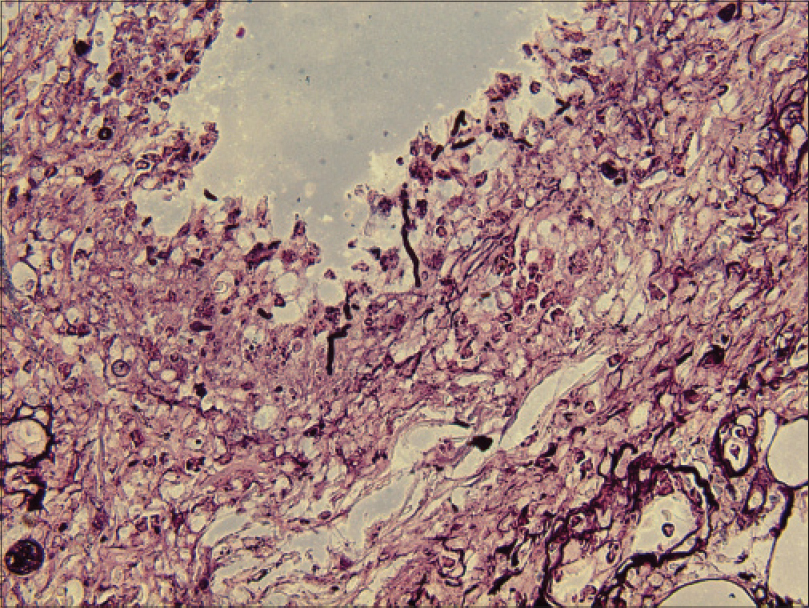

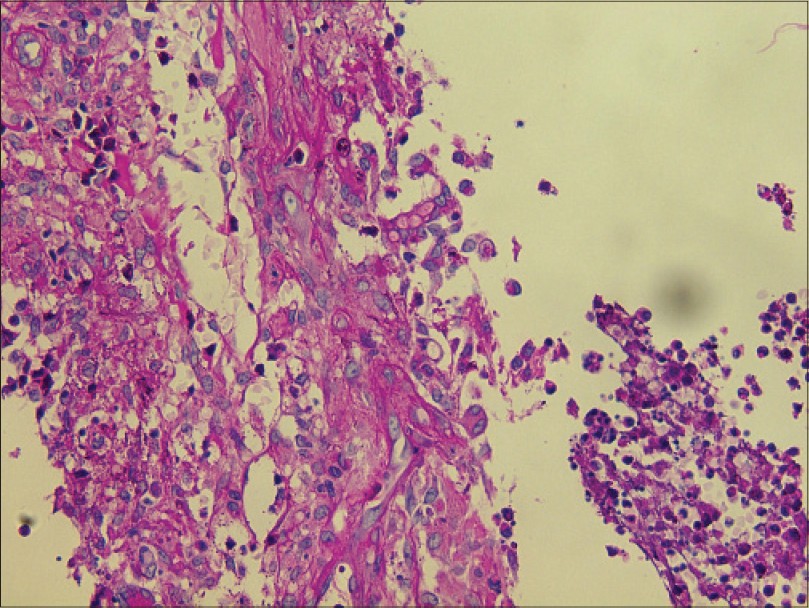

Laboratory investigations showed leukocytosis (white blood cell: 15.6 × 109/L), anemia (hemoglobin 10.1 g/dL) and elevated C-reactive protein (148.4 mg/L). Histopathological examination showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and dermal edema with neutrophilic and focal granulomatous inflammation, surrounding zones of frank necrosis [Figure - 2] and [Figure - 3]. Periodic acid-silver methenamine [Figure - 4] and periodic acid-Schiff [Figure - 5] stain showed slender, thick-walled, septate hyphae within neutrophilic debris. Occasional branching hyphae with a random, acute angled pattern were observed. Culture of necrotic tissue from the lesion on the right forearm was negative. Further evaluation of the patient, including blood culture and chest radiography, showed no evidence of disseminated disease.

|

| Figure 2: Dense inflammation and necrosis within the entire dermis and extending to the subcutaneous tissue (H and E, ×400) |

|

| Figure 3: Cellular infiltrate containing lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils and multinucleated giant cells within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (H and E, ×100) |

|

| Figure 4: Hyaline septate hyphae (periodic acid-silver methenamine, ×400) |

|

| Figure 5: Hyaline spore (periodic acid-Schiff, ×400) |

Oral treatment with itraconazole, 200 mg twice a day every 12 h, was instituted for 2 weeks and the patient was discharged at his request. Later, he suffered from diarrhea at home and died. A second culture from the ulcer fluid obtained prior to discharge was performed in Sabouraud glucose agar medium. We obtained white cottony colonies [Figure - 6] at first and 15 days later, we obtained smooth, velvety, grayish-brown colonies. We identified the pathogen as Scedosporium apiospermum by morphological characterization. Species identification was performed with matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. Analysis was conducted by the MALDI Biotyper software version 3.0 (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) with Filamentous Fungi Library database version 1.0 (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry identification showed the best match with S. apiospermum (score >2.0).

|

| Figure 6: Velvety white colonies |

S. apiospermum is a ubiquitous filamentous fungus that may cause severe and often fatal infection in immunocompromised hosts. It is an emerging opportunistic pathogen with a rising incidence possibly because of the widespread use of immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids, antineoplastic agents and broad-spectrum antibiotics. S. apiospermum causes mycetoma (by its sexual phase, Pseudallescheria boydii) and deep invasive infections and can disseminate in bone marrow transplant recipients and immunosuppressed individuals with a mortality rate as high as 55%.[1],[2],[3]

In the diagnosis of this infection, it is important to recognize S. apiospermum which resembles Aspergillus spp. clinically and histopathologically. Although its conidia are distinctive and can facilitate the identification of Scedosporium species, they are absent under most growth conditions and are rarely found in tissue samples. However, current findings that these fungi can involve the eccrine coil might be a clue to diagnosis because sweat in the eccrine unit contains many nitrogenous compounds providing a favorable environment.[4]

Culture is currently the gold standard for definitive identification of the fungus from tissue specimens. However, false-negative results are common because of variables such as specimen quality, delayed processing and growth suppression by antifungal medications prescribed to the patient prior to specimen procurement. Diagnosis could be delayed by negative or slow-growing cultures or contamination of culture with other fungi and bacteria.[1] Thus, histopathologic examination remains a valuable tool in the prompt diagnosis of invasive fungal infection, despite its limitation in definitive species identification. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry or polymerase chain reaction-based detection method would help in the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections at an early stage of infection.

Treatment of S. apiospermum can be challenging. The azole antifungals may be effective. The in vitro susceptibility to itraconazole, posaconazole and voriconazole was highly variable; nevertheless, the lowest minimal inhibitory concentration values were frequently described for voriconazole. Voriconazole appears to be a front-runner and the recommendation to use posaconazole in patients with S. apiospermum infection was only marginally supported. Some clinicians prefer miconazole or itraconazole for initial management. Resistance to both itraconazole and fluconazole has been reported. Troke et al. analyzed 107 cases of Scedosporium infection.[5] A successful therapeutic response was achieved in 57% of the patients treated with voriconazole.

In our case, the underlying factor leading to this opportunistic fungal infection was long-term therapy with corticosteroids. Initially, we mistook S. apiospermum for Aspergillus. Hence, we chose to administer itraconazole 400 mg daily for our patient. Two weeks later, the second fungal culture grew colonies which were identified as S. apiospermum.

All fungal infections in immunocompromised patients can be life-threatening. Accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment are important. We emphasize the importance of avoiding mistakes in identifying the fungal isolates on the basis of histopathology or early culture, especially in an acutely ill patient.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Cortez KJ, Roilides E, Quiroz-Telles F, Meletiadis J, Antachopoulos C, Knudsen T, et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008;21:157-97.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Perlroth J, Choi B, Spellberg B. Nosocomial fungal infections: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Med Mycol 2007;45:321-46.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Nesky MA, McDougal EC, Peacock JE Jr. Pseudallescheria boydii brain abscess successfully treated with voriconazole and surgical drainage: Case report and literature review of central nervous system pseudallescheriasis. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:673-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Harrison MK, Hiatt KH, Smoller BR, Cheung WL. A case of cutaneous Scedosporium infection in an immunocompromised patient. J Cutan Pathol 2012;39:458-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Troke P, Aguirrebengoa K, Arteaga C, Ellis D, Heath CH, Lutsar I, et al. Treatment of scedosporiosis with voriconazole: Clinical experience with 107 patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:1743-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,529

PDF downloads

3,466