Translate this page into:

Skin manifestations of acromegaly - a study of 34 cases

Correspondence Address:

Kavita R Arya

23, Sopan Baug Co-operative Housing Society, Pune - 411 001

India

| How to cite this article: Arya KR, Krishna K, Chadda M. Skin manifestations of acromegaly - a study of 34 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1997;63:178-180 |

Abstract

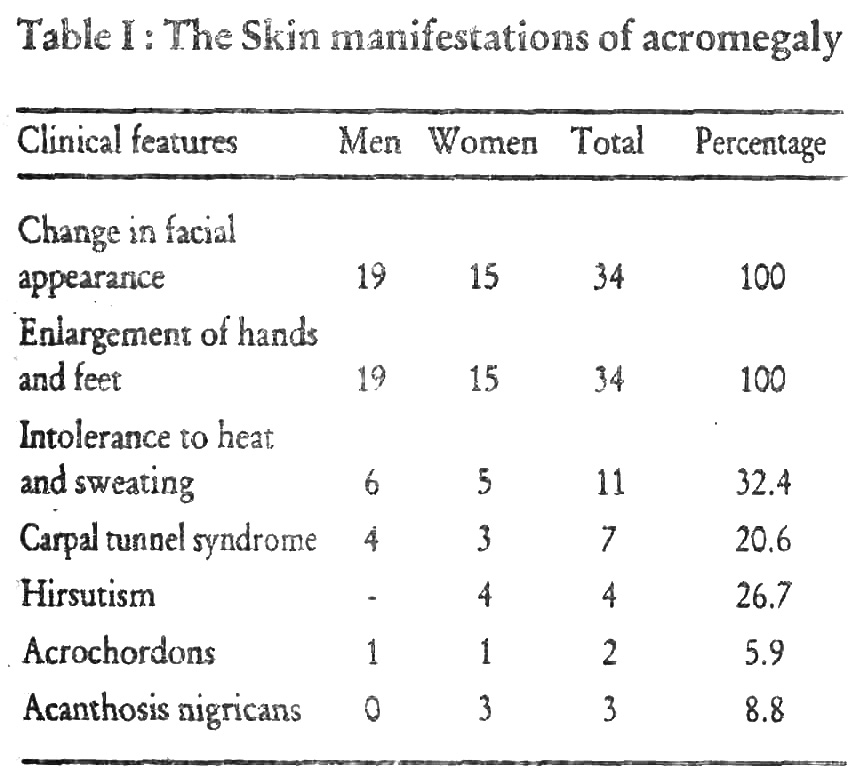

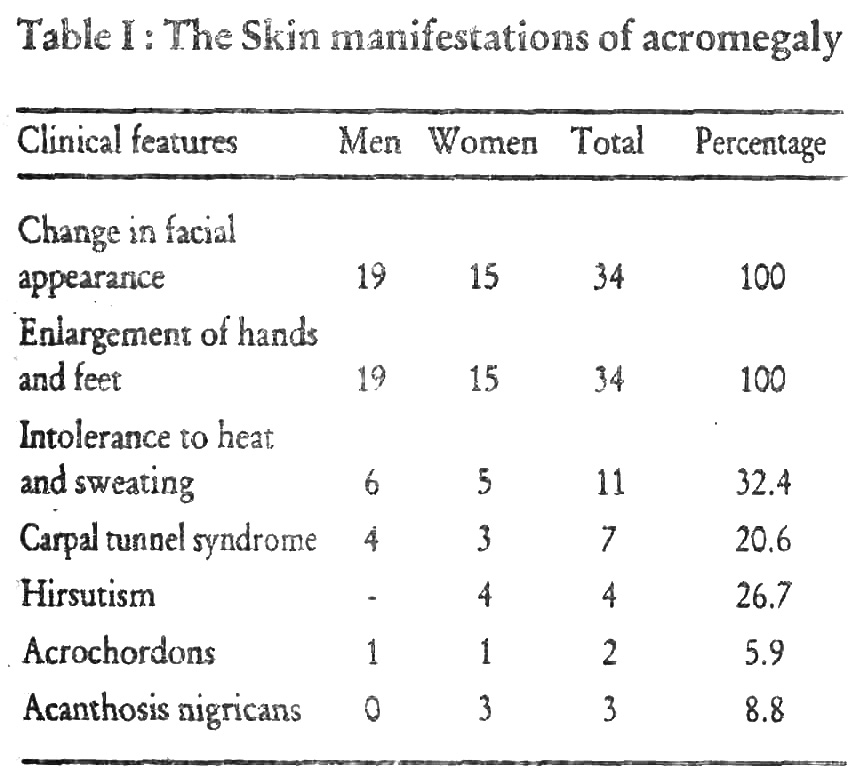

The common dermatological manifestations seen in 34 cases of acromegaly were changes in facial appearance, enlargement of hands and feet, intolerance to heat and sweating, carpal tunnel syndrome, hirsutism, acrochordons and acanthosis nigricans. The mean estimated age of onset was 32.8 years in males and 31.7 years in females, while the mean age at the time of diagnosis was 38.6 years and 36.1 years for males and females respectively, with a slight male preponderance noted.

The term "acromegaly" was coined by Pierre Marie in 1886,[1] though he was not the first person to describe this clinical entity and in fact he had refuted the idea of pituitary hyperfunction. Minkowaski in 1887, when describing a patient with headache and hemianopia, was the first to suggest that pituitary dysfunction caused acromegaly.[1]

Excessive secretion of growth hormone starting after or around the time of closure of epiphyses of the long bones results in acromegaly. Gigantism results when the excessive secretion of growth hormone begins before the epiphyses close. However, patients with gigantism almost always develop the clinical features of acromegaly because over-production of growth hormone continues long after closure of the epiphyses of the long bones. The lesions responsible for the excessive production may be hypothalamic, hypophyseal or ectopic in origin producing growth hormone or growth hormone releasing factor.[1]

Subjects and Methods

The study was conducted at the Department of Medicine and Endocrinology, KEM hospital, Mumbai during a period of five years. Acromegaly was diagnosed on the basis of basal and post glucose growth hormone levels measured by radioimmunoassay. The upper limit of growth hormone levels is 5 ng/ml which should suppress below 1ng/ml after a glucose load.

Results

The mean estimated age of onset (calculated by age at presentation in years - duration of symptoms in years) was 32.8 years (range 17-58 years) in males and 31.7 years (range 6-57 years) in females. The mean age at the time of diagnosis for males was 38.6 years (range 22-65 years) and for females was 36.1 years (range 12-57 years). The incidence in males was slightly higher, 19 men (55.8%) and 15 women (44.2%).

The skin manifestations including the presenting symptoms and those detected at the time of diagnosis are listed in [Table - 1]

Discussion

Acromegaly is not a common disease. Alexander et al from a study in the north of England suggested a prevalence of diagnosed cases of 40 per million of population.[2] The sex distribution of our cases showed slight male predominance (19 men, 15 women) comparable with Nabarro′s series (133 males, 123 females).[3] Two of our patients, both females, presented to us during adolescence, with rapid increase in height. After the epiphyses have fused, early clinical changes are enlargement of fingers - need to have rings enlarged and changes in shoe size. The estimated age of onset in this series varied from 6 to 57 years in females (mean 31.7 years) and 17 to 58 years in males (mean 32.8 years), comparable with Nabarro′s series of 256 patients.[3]

Acromegaly causes changes in the skin, cardiovascular, respiratory, central nervous, musculoskeletal and endocrine systems. In the skin, changes are most pronounced in the connective tissue of the dermis, with an increase in the content of glycosaminoglycans with proportional increases in chondroitin and dermatan sulphate, and the attendant retention of water. Also, there is hyperplasia of the epidermis and dermal appendages, along with effects on the pilosebaceous structures by potentiating the effectiveness of the available androgen.[4]

Thickening of the subcutaneous tissues affecting particularly the face, the fingers and the heel pads was present in all patients. Hyperhidrosis was noted in 32.3% of the patients. The prevalance of increased sweating reported in previous series has varied from 65%,[5] to 88%.[6] Three young women (8.8%) with severe acromegaly and very high growth hormone levels, had typical acanthosis nigricans, most obvious in the axillae and nape of the neck. This is well recongnised in young acromegalics both male and female,[7] and has a reported incidence of 29%.[6] Four of our female patients (26.6%) had hirsutism mainly involving chest, sacral area and extremities with relative sparing of the face comparable with 24% incidence in Nabarro′s series.[3] Skin tags, especially over the trunk were reported in 27%,[8] to 45%.[6] Two of our patients (5.9%) had acrochordons over the neek, axillae and trunk. However, Nabarro reported cutis vertices gyrata due to soft tissue thickening of the scalp in 4 patients,[3] which was not seen in any of our cases.

The features of skeletal overgrowth were seen in all patients - protrusion of lower jaw with malocclusion of teeth, wide spacing of teeth, and enlargement of hands and feet. Carpal tunnel syndrome, with tingling and parasthesiae in the hands, more at night was seen in seven of our patients (20.6%), 4 men (21%) and 3 women (20%) respectively. The incidence reported in other series has been 25%.[3]

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. P.S. Menon, Professor and Head, Department of Endocrinology, K.E.M. Hospital for her suggestions and guidance. We also thank the Dean, Seth G.S. Medical college and K.E.M. Hospital for permitting us to publish hospital data.

| 1. |

Randall RV. Acromegaly and gigantism. In: Endocrinology, second edition, editors, De Groot LJ, Besser GM, Cahill GF Jr et al. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1989;330-350.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Alexander L, Appelton D, Hall R et al. Epidemiology of acromegaly in the New Castle region Clin Endocrinol 1980;12:71-79.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Nabarro JDN. Review - acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol 1987;26:481-512.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Freinkel RK, Freinkel N. Cutaneous manifestations of endocrine disorders, In: Dermatology in General Medicine, Third ed, volume 2, Editors, Fitzpatrick TB, Eizen AZ, Wolff K et al, Mc Graw Hill Information Services Company, New York, 1987;2063-2081.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Jadresic P. The acromegaly syndrome: relation between clinical features, growth hormone values and radiological characteristics of pituitary tumours. Quart J Med 1982;51:189-204.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Tyrrell JB, Wilson CB. Pituitary syndromes. In: Surgical Endocrinology Clinical Syndromes, Editor, Freisen SR, JB Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1978;304-324.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Brown J, Winkelmann RK, Randall RV. Acanthosis and pituitary tumors: Report of eight cases, JAMA 1966;198:619-623.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Davidoff LM. Studies in acromegaly III. The anamnesis and symptomatology in one hundred cases, Endocrinology 1926;10:461-483.

[Google Scholar]

|