Translate this page into:

Social aspects of syphilis based on the history of its terminology

2 2nd Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Attikon General University Hospital, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

3 History of Medicine Department, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Correspondence Address:

Marianna Karamanou

M.D: 4 Str Themidos, 14564, Kifissia, Athens

Greece

| How to cite this article: Kousoulis AA, Stavrianeas N, Karamanou M, Androutsos G. Social aspects of syphilis based on the history of its terminology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:389-391 |

Introduction

Syphilis is a chronic disease with a waxing and waning course, which occurs worldwide and is mainly transmitted by sexual contact. [1] Its manifestations have been described for centuries and its name is a product of lengthy debates and discussions. The history of syphilis also provides us a lesson of how we should treat pandemics.

The European Terminology

Since the European emergence of syphilis, the terminology of this sexually transmitted epidemic has been a far from simple matter that triggered and reflected complex social balances. The fact that syphilis was being labelled by nationality led to its participation in political confrontations.

The closing years of the 15 th century proved to be quite determinant both for the epidemiology of syphilis and the arguments for a proper name. As it was quite hard for the medical world of that time to apply an acceptable term for the disease, it is equally difficult for today′s researcher to sort out an objective view after studying the debates, mostly between the century′s developed countries, for the finding of a suitable name.

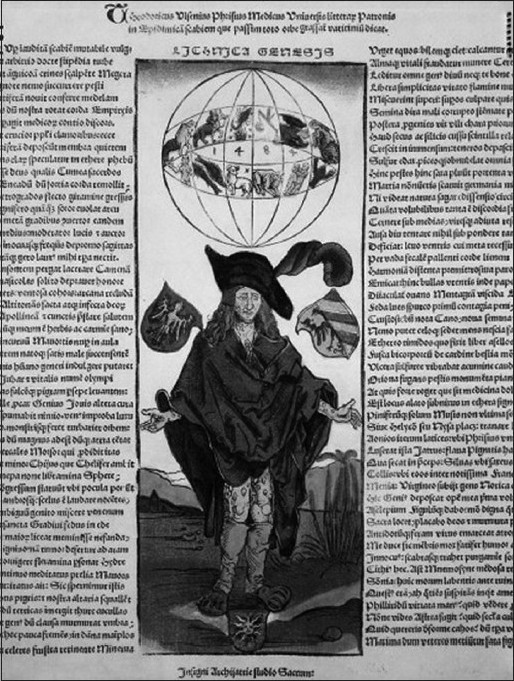

The first major outbreak that occurred in Naples in the mid-1490s [2] gave birth to the name Italian disease or The disease of Naples, mostly popular among the French population. [3] This was an unacceptable term for the residents of the Italian city who preferred the name French disease (also known as Morbus Gallicus, or by the French term, Maladie Franηaise), a term widely used in Poland and Germany too [Figure - 1], [4] but also in Great Britain, as we later discover the words malady of France in William Shakespeare′s play Henry V. [5] The correlation of syphilis with France arose because of the activities of King Charles VIII′s (1470-1498) French soldiers, who besieged and took Naples in 1495 and, therefore, were considered to be responsible for the first epidemic of the disease.

|

| Figure 1: A 1496 illustration of syphilis or the French Disease[3] |

The name Spanish disease is attributed to either the Dutch or the Italians, and came up based on the Columbian theory of the origin of syphilis, which suggests that syphilis was a New World disease brought back by the crewmen of Columbus, who travelled to America serving the Spanish colonization. [3]

In addition to the above stated names, there are books and articles, of the Renaissance era, which refer to syphilis as Polish disease (a name found in the Russian literature) and Christian disease (mostly popular among Turkey′s Muslims and Arabs). [3] However, the term Maladie Anglaise or British disease, often attributed to the French or the Tahitians, does not seem to refer to syphilis. That confusion probably resulted from the book of the 18th century physician, George Cheyne (1671-1743), called The English Malady, which analyzed various neurological diseases but not syphilis. [6]

The fact that in various countries people kept referring to syphilis by names with a national texture came as a result of the foreign trade ships activities. Sexual contacts between sailors and local prostitutes were commonplace, and those women were thought to be the main source of the disease, a perception that lasted for a few centuries. [7] The national names intended on putting responsibility on a particular country for this deadly disease [3] and, therefore, many politicians had tried to repulse the relevant term and come up with one that could historically blame an unfriendly nation. In these historical times, infectious diseases were thought to emerge due to social migration; therefore, the use of terminology on international relations and the labelling of a disease could benefit both governmental plans (conceivably lessening the chance of sexual contact with foreigners and diminishing the spread of an alien infection) and the religious agenda concerning the sinful sexually transmitted diseases (priests denounced the wickedness and immorality of an age that had provoked God′s anger in the form of a deadly pandemic). [8] The denomination of a disease as the property of particular nations suggested a disorder of which sufferers need unequivocally to be ashamed.

Since the earliest emergence of epidemics, one of the first human responses to them has been to question their origin. Social reactions to syphilis in the 15th century resemble the responses to AIDS 500 years later. With the alleged contact contagion, the human stampede and the immature medical knowledge, both syphilis and AIDS (first thought to have resulted from increased human travelling) [8] created a seemingly inevitable xenophobia-like feeling. Unfortunately, a similar reaction occurred during the recent 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, which was initially called the "Mexican flu." The fact that Mexican nationals and Mexican commodities were shunned globally (notably, in the United States, some media personalities characterized Mexican immigrants as disease vectors who were a danger to the country) [9] comes to prove that the lessons from the past are sometimes ignored. Humanity once again has proven unprepared to face maturely a pandemic, even though half a millennium ago, syphilis had posed the perfect example of how a disease labelled by nationality can signify contempt and dread. [6]

The Non-National Names

Apart from the already mentioned national names, there are a few more interesting terms that have been used to describe syphilis. Particularly for India, it seems that Vasco da Gama′s (1460-1524) crew introduced syphilis to Indian people after they arrived at Calicut in 1498. In fact, Tamils developed feelings of contempt against those responsible for the disease - the Europeans - and used the term Parangi for them, meaning syphilitics. [10]

In the 15 th century, the disease spread rapidly in Scotland, among the mercenaries of Perkin Warbeck (1474-1499), a pretender to the English throne. The name they used for syphilis was the Grandgore (deriving from the old French language where grand means great and gorre is used for syphilis, as phrased by the Town Council of Edinburgh in 1497: "This contagious sickness callit the Grandgor0"). [11] The spread of syphilis led to the passing of the "Grandgore act," which set Scottish islands in the Firth of Forth to serve as quarantine and places of compulsory retirement for syphilitics. [12] In the final years of the 15th century and in the onset of the 16 th century, the observations of the secondary stage of syphilis, which is characterized by the development of a rash or skin eruption, originally gave rise to the term Great Pox in order to differentiate the disease from the smallpox. [13] That name, however, turned out to be misleading as smallpox, the Variola disease, proved to have a higher mortality rate. [14] Even though the term syphilis had already been accepted, later on we find two additional interesting terms: the euphemistic Cupid′s disease in 18 th century Italy′s culture circles [15] and the intimidating Black lion in the 1874 Dunglison′s medical dictionary, a name given to the syphilitic ulcer under which the British soldiers suffered greatly in Portugal. [16]

Although these names lack the political implications of the above, they still prove that syphilis remained a dark contagion for many centuries.

Forming and Etymology of the Present Term

The present name for the disease derives from Syphilus, the protagonist of the poem "Syphilis sive morbus gallicus," written by Girolamo Fracastoro (1478-1553) in 1530. [17] According to the original Greek tradition, the name Syphilus stems from the myth of Niobe in reference to Mount Sypilus or Sipylum in today′s Turkey′s Aegean region. [18]

As a learned Renaissance scholar, Fracastoro was familiar with Greek and Roman literature and, as Syphilus was a Greek shepherd, it is the Ancient Greek language that provides the relevant etymology of the term. [19] Apart from the hypothesis that it could just be a mythological connected idea, there are at least four possible sources for the word syphilis: [3] Firstly, the word "susphilos" (meaning lover of swine, from the Homeric Greek or Latin "sus" and Greek "philos"). Secondly, "symphilos" (meaning one who loves or makes love). Thirdly, "asyphilos" (meaning vile and contemptible, coming probably from the Homeric Greek). Finally, "sepalos" (meaning infected and obscene, with the same etymology as sepsis). [20]

Fracastoro introduced syphilis as the disease that infected Syphilus as a punishment from the God Apollo for the defiance shown toward him. [19] Using this popular Greek mythological frame (a disease striking as a result of divine intervention), the Veronese doctor phrased the most probable approach of his contemporaries: syphilis was a disgraceful, immoral disease. Furthermore, all the possible etymological roots for the final term can contain the major social viewpoint of the era for syphilis: like a vile or amatory person, a syphilitic deserves to be condemned to the level of a swine.

Conclusion

Either an unwanted legacy, a chance to target an opposed nation or a literary complex term, syphilis has a terminology history full of debates, disagreements and interesting social aspects. However, when studying the history of a widespread epidemic, the most important knowledge is the acquisition of the lessons of the past, so that we can be prepared for the future. The recent examples come to show that syphilis′ history still has a lot to teach us.

| 1. |

Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: Review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999;12:187-209.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Tognotti E. The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Europe. J Med Humanit 2009;30:99-113.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Kontokostas K, Kousoulis A. Syphilis in history and arts. Athens: John B. Parisianos; 2008.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Eatough G. Fracastoro's Syphilis. Introduction, Text, Translation and Notes. Liverpool: Francis Cairns; 1984.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Shakespeare W, Henry V. Act 5. Massachusetts: Digireads; 2005.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Cheyne G. The English Malady (1733) edited by Roy Porter. London: Routledge; 1991.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Fournier A. Syphilis et marriage. Paris: G. Masson; 1880.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Morens DM, Folkers GK, Fauci AS. Emerging infections: A perpetual challenge. Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8:710-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Schoch-Spana M, Bouri N, Rambhia KJ, Norwood A. Stigma, health disparities, and the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic: How to protect Latino farmworkers in future health emergencies. Biosecur Bioterror 2010;8:243-54.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Subba Reddy DV. Antiquity of syphilis (venereal diseases) in India. Indian J Vener Dis 1936;2:103-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Pearce JM. A note on the origins of syphilis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64:542,547.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Inchkeith. In: Lewis S, editor. A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland. Edinburg: Peter Hill; 1846. p. 555-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Shelton MH. Syphilis: Is it a mischievous myth or a malignant monster? California: Health Research, Mokelumne Hill; 1962.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Barquet N, Domingo P. Smallpox: The triumph over the most terrible of the ministers of death. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:635-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Sabbatani S. Physicians and philosophers tackling Cupid's disease: Combating syphilis in the 18 th century. Infez Med 2008;16:108-15.

th century. Infez Med 2008;16:108-15.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Dunglison R. Dunglison's Medical Dictionary - A Dictionary of Medical Science. Philadelphia, USA: Collins; 1874.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Haas LF. Girolamo Fracastoro 1484-1553. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991;54:855.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Perrot G. History of art in Phrygia, Lydia, Caria and Lycia. London: Marton Press; 2007. p. 62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Thyresson N. Girolamo Fracastoro and Syphilis. Int J Dermatol 1995;34:735-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Stamatakos I. Dictionary of the ancient Greek language. Athens, Greece: Phoenix; 1972.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

6,041

PDF downloads

3,387