Translate this page into:

Sporotrichoid spread of locoregional bacille Calmette-Guerin infection following intralesional immunotherapy for verruca vulgaris in an immunocompetent adult

Corresponding author: Dr. Suman Patra, Department of Dermatology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. patrohere@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Patra S, Kaur M, Narula S, Asati DP, Chaurasia JK. Sporotrichoid spread of locoregional bacille Calmette-Guerin infection following intralesional immunotherapy for verruca vulgaris in an immunocompetent adult. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023;89:733-5

Dear Editor,

Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) is a live attenuated vaccine given routinely in new-borns as a part of the national immunisation schedule. In adults, it has been used as immunotherapy for various malignancies, most notably carcinoma of the urinary bladder.1 Intralesional immunotherapy with BCG has recently gained interest in dermatology for the management of resistant cutaneous and genital warts.2 Disseminated or regional spread of BCG infection is possible and has been reported rarely in literature. It was seen mostly in children with primary immunodeficiency or adults following immunotherapy for malignancies. We report an unusual case of locoregional spread of BCG infection after intralesional injection in warts in an otherwise healthy adult.

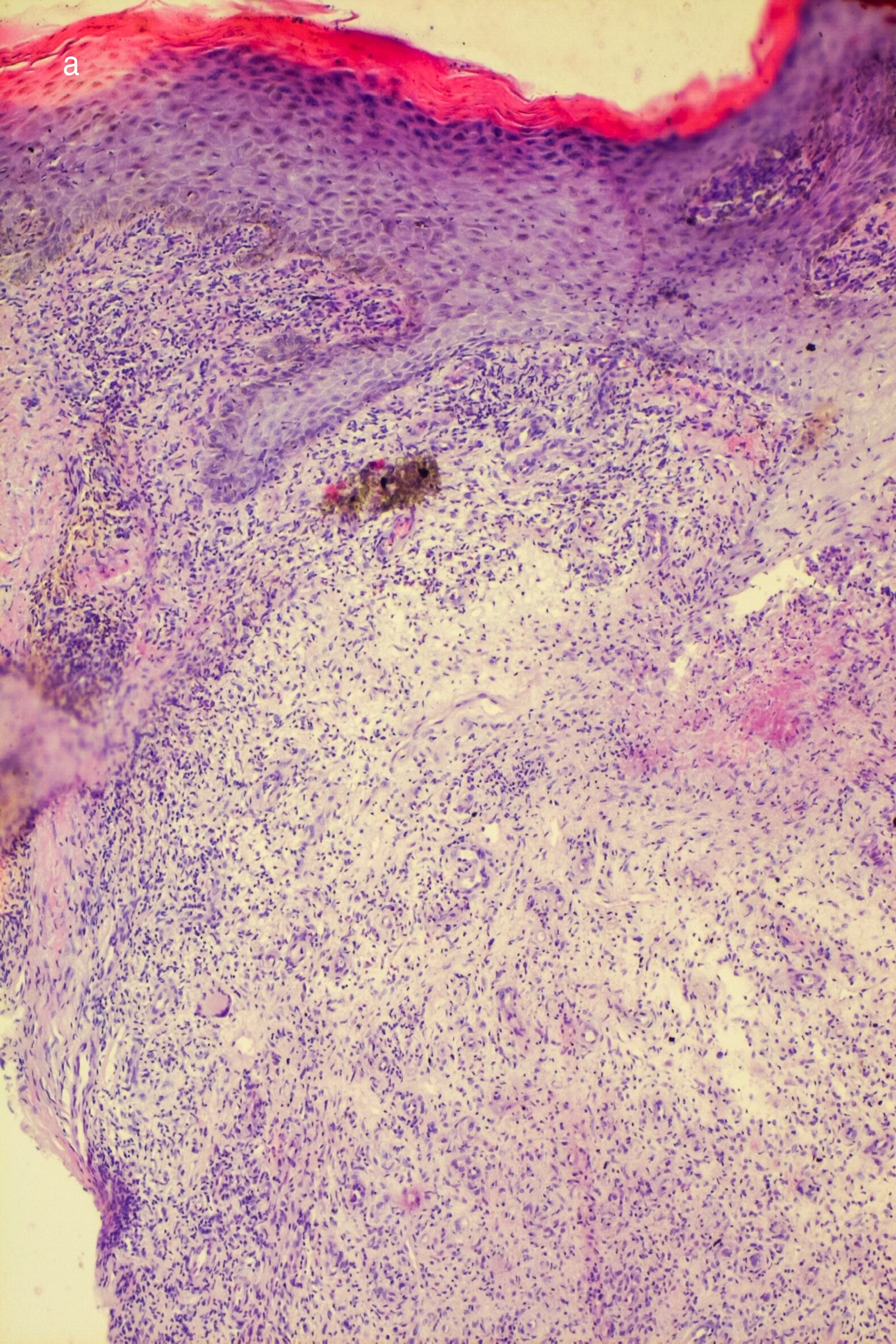

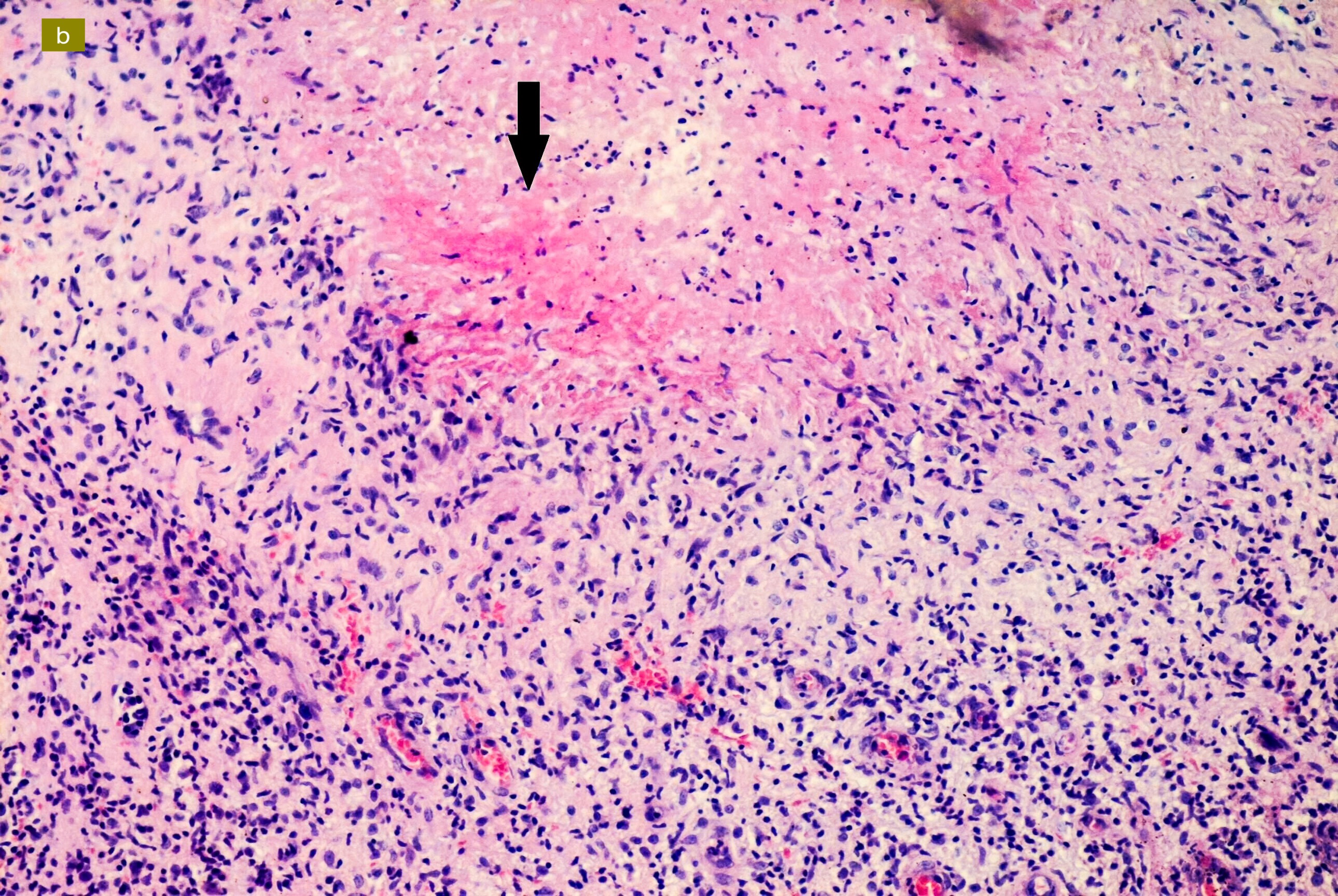

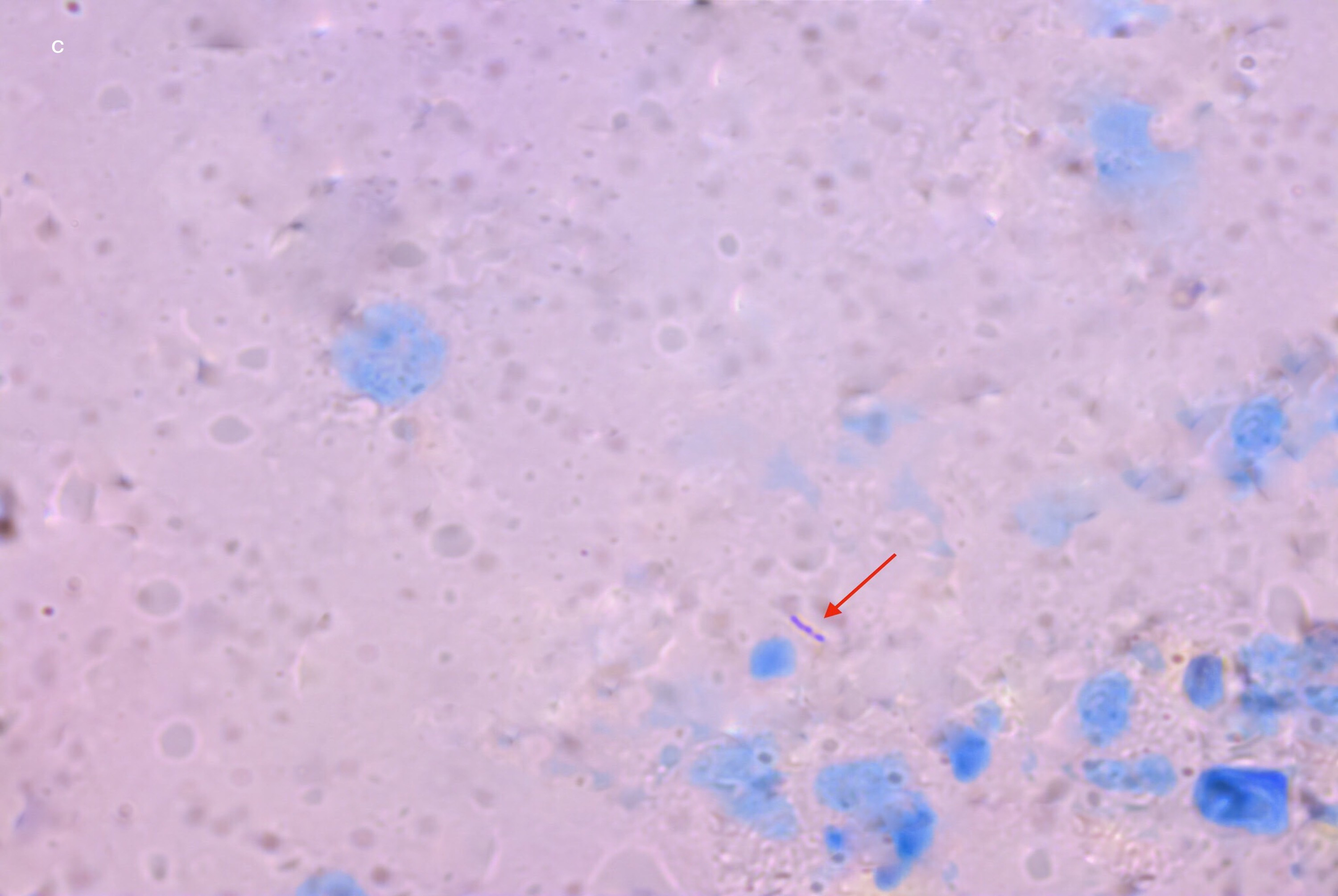

A 59-year-old female received immunotherapy with the BCG vaccine for warts on her right foot 6 months back. She received a total of 0.1 mL of vaccine, injected intralesionally divided into three warts under aseptic precautions. She returned to dermatology OPD of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal, after 3 months with partial subsidence of warts [Figure 1a] but complained of multiple painful nodules over her right leg and thigh associated with low-grade intermittent fever. A nodule initially appeared over the right shin 1 month after immunotherapy which ruptured with purulent discharge in 1-month time. Subsequently, two similar lesions developed over the right popliteal fossa and thigh. On examination, two well-defined mildly tender, warm and fluctuant violaceous swellings of size 3 × 2 cm were noticed over the right shin and upper part of the leg [Figure 1b] along with a few sinuses over the proximal thigh [Figure 1c]. A large non-matted and firm lymph node of size 4 × 4 cm was palpable over the right superficial inguinal region [Figure 1c]. Other lymph node groups were not enlarged and systemic examination did not reveal any other abnormalities. A provisional diagnosis of locoregional BCG infection was made. She was BCG vaccinated in childhood without any complications and had no history of pulmonary tuberculosis or serious systemic infections. Her routine investigations including chest radiograph were within normal limits except for mild iron deficiency anaemia. Her retroviral status was negative. Skin biopsy from one of the lesions showed epithelioid cell granulomas with caseation necrosis (Figures 2a and 2b). Aspirated pus from the swelling over the right leg showed acid-fast bacilli [Figure 2c] and positive cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex further confirmed the diagnosis. She had moderate improvement after 2 months of antitubercular therapy.

- Partial subsidence of warts with scarring (white arrow) and few remnant warts (black arrow) over the right foot

- Two fluctuant abscesses over the right leg

- Two sinuses over the thigh (white arrow) with enlarged inguinal lymph node (black arrow)

- Epidermal hyperplasia and upper dermal granulomatous infiltrate with giant cells (hematoxylin and eosin 100×)

- Caseating necrosis (arrow) (hematoxylin and eosin 400×)

- Acid-fast Bacilli in aspirated material from leg nodule (red arrow). (1000×, Ziehl Neelsen stain)

BCG vaccine strain is an attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, prepared from repeated subcultures to preserve immunogenicity while minimising its virulence. Complications like injection site abscesses and regional lymphadenopathy are common after vaccination.3 Chronic infections occur rarely, and it is termed as BCGitis in case of local and regional spread, whereas the distant or disseminated infection, is known as BCGosis.4 Most of the cases of BCGosis, till date in literature are reported in children with known primary immunodeficiency disease or in adults as a complication of intravesical BCG instillation for carcinoma urinary bladder.4,5 They commonly present as miliary tuberculosis, lymphocytic meningitis, arthritis, and genitourinary involvement.5 Immunotherapy is usually reserved for the management of resistant warts. In our case, the patient had recurrences two times after radiofrequency ablation. Though the Mycobacterium indicus pranii vaccine is the preferred choice for immunotherapy, due to its unavailability, the BCG vaccine was used. In cases of cutaneous inoculation as immunotherapy, we were unable to find any report of distant infection beyond the site of inoculation. This made our case unique as it showed the spread of infection proximally with multiple lesions in an almost linear fashion along with regional lymphadenopathy. Our patient did not have diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease or any other acquired immunodeficiency state. People having defects in interferon-γ mediated immunity, termed as Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases, can be vulnerable to weakly virulent species of mycobacteria and develop serious systemic infections.6 As our patient did not have a history of any serious systemic infection, primary immunodeficiency workup was not done. Older age and malnutrition could also be risk factors for disseminated infection. She was kept under regular follow-up and monitoring.

The diagnosis, in most cases, is based on molecular methods or culture. Culture may be negative due to low bacterial load. Cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test, a highly sensitive and specific diagnostic tool, detects Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex but cannot differentiate between Mycobacterium tuberculosis and bovis.7 So, in our case, its positivity might indicate infection with the BCG vaccine strain used for inoculation. Mycobacterium bovis is inherently resistant to pyrazinamide. The treatment regimen is not standardised. Longer duration of treatment was considered in some guidelines.8 We planned for treatment with three antitubercular drugs, that is, rifampicin, isoniazid, and ethambutol, for a total period of 9 months.

This case highlighted a possible complication of intralesional immunotherapy with BCG, even in healthy adults.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mechanisms of BCG immunotherapy and its outlook for bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:615-625.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BCG vaccine for immunotherapy in warts: is it really safe in a tuberculosis endemic area? Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:168-172.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heterologous effects of infant BCG vaccination: potential mechanisms of immunity. Future Microbiol. 2018;13:1193-1208.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- BCG related complications: A single center, prospective observational study. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2015;2:75-78.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Disseminated BCG: Complications of intravesical bladder cancer treatment. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:362845.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Inborn errors of IL-12/23- and IFN-gamma-mediated immunity: molecular, cellular, and clinical features. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:347-361.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of lymph node tuberculosis using the GeneXpert MTB/RIF in Tunisia. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2015;4:270-275.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]