Translate this page into:

Systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma with secondary cutaneous involvement

Correspondence Address:

Amit S Murkute

OPD No. 33. Department of Skin and VD, B. J. M. C., Pune - 411 001, Maharashtra

India

| How to cite this article: Murkute AS, Damle DK, Doshi BR, Belgaumkar VA. Systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma with secondary cutaneous involvement. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2015;81:208-210 |

Sir,

A 28-year old female presented with a large swelling over the left flank for 1½ months and a painful swelling over the left groin since 15 days. Clinical examination revealed a 25 × 30 cm sized, single, firm, non-tender, erythematous, infiltrated plaque studded with reddish-brown nodules [Figure - 1]. Another 8 × 10 cm firm, non-tender nodule with pustules and crusts on the surface was noted in the left inguinal region. Systemic examination was unremarkable.

|

| Figure 1: Erythematous, infiltrated plaque studded with many reddish-brown nodules with overlying crusting at places on the left flank |

Complete hemogram, peripheral blood smear, liver and renal function tests were within normal limits. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) from the inguinal region showed atypical cells and mature lymphocytes. Chest X-ray revealed hilar lymphadenopathy. CT abdomen showed multiple enlarged inguinal, pelvic, and central abdominal lymph nodes, and whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) scan revealed activity in the left inguino-femoral, pelvic, retroperitoneal and thoracic lymph nodes and diffuse splenic involvement.

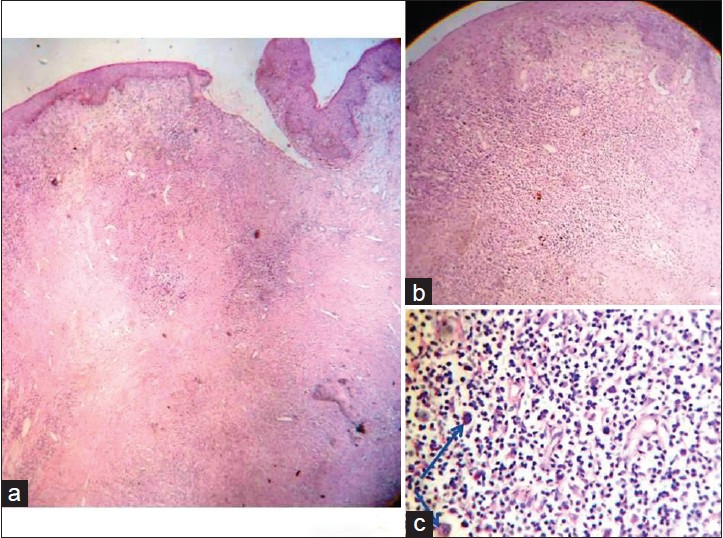

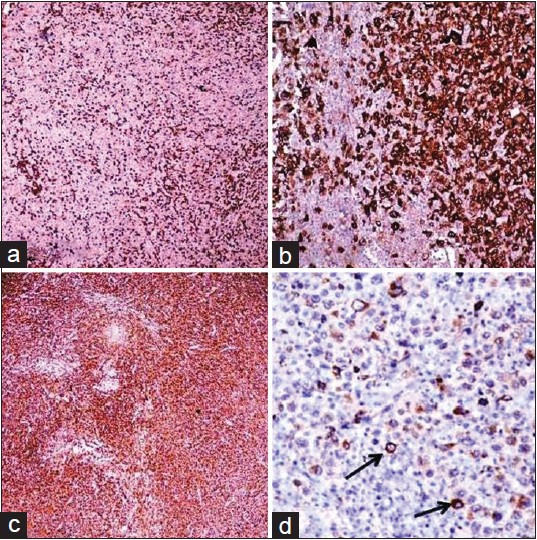

Biopsy from the cutaneous mass revealed a diffuse dermal infiltrate [Figure - 2]a comprising of sheets of large atypical pleomorphic lymphocytes [Figure - 2]b with hyperchromatism [Figure - 2]c. Epidermotropism was absent. Biopsy of left inguinal lymph node showed a diffuse infiltrate with hyperchromatic large atypical pleomorphic cells and bizarre giant cells.Immunohistochemistry both of the inguinal lymph node and skin lesion showed CD3 positivity in the surrounding small lymphocytes [Figure - 3]a and a strong positivity for CD30 (Ki-1) [Figure - 3]b, leukocyte common antigen (LCA/CD45) [Figure - 3]c, and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) [Figure - 3]d in the large atypical lymphoid cells. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) could not be tested due to nonavailability. [1] Based on these findings a diagnosis of CD30+ cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) secondary to systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma, stage IVB (T2 N3 M1) was made.

|

| Figure 2: (a) Diffuse interstitial infiltrate involving the entire dermis (H and E, scanner view); (b) diffuse pleomorphic lymphocytic infiltrate (H and E, ×10); (c) large atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatism (arrow) and a few eosinophils (H and E, ×40) |

|

| Figure 3 (a) Immunohistochemical staining profile showing CD3 positivity in surrounding small lymphocytes on lymph node biopsy; (b) diffuse CD30+ large atypical lymphocytes on lymph node biopsy; (c) diffuse cells staining positive with LCA on lymph node biopsy; (d) EMA+ ve large atypical lymphocytes (arrow) on lymph node biopsy |

The patient was started on CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide 800 mg/m 2 , vincristine 2 mg, doxorubicin 50 mg/m 2 and prednisolone 60 mg/m 2 ). After six cycles, there was 75% improvement in the cutaneous lesion. With additional local radiotherapy (total dose 4500 cGy) there was a near complete resolution of the skin lesion [Figure - 4]. However, there was no improvement in systemic disease as evidenced by post-chemotherapy whole-body PET scan which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid fresh lymph nodes in paratracheal, pre- and para-caval, pre- and para-aortic regions, and right supraclavicular region, along with pre-existing intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy and diffuse splenic involvement. The patient succumbed to esophageal compression within 1 year of diagnosis.

|

| Figure 4: Almost complete regression of the skin lesions following chemotherapy and radiotherapy |

Anaplastic large cell lymphomas present as primary cutaneous (PC-ALCL) disease or systemic disease with secondary cutaneous involvement, both of which are distinct entities with different clinical and biological features. Primary cutaneous disease [2] presents as solitary or multiple large ulcerated nodules, predominantly on trunk, without evidence of mycoses fungoides or another type of primary cutaneous T cell lymphoma. [3] Histologically it is characterized by large tumor cells with pleomorphic cytomorphology, majority of which express CD30 (Ki-1) antigen. [1]

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma has a favorable prognosis with a 5-year survival of >90% and needs to be differentiated from cutaneous disease secondary to systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as the latter has a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival of <45%. [2] However, presently there are no reliable biological markers to distinguish the two. Though ALK expression in the skin indicates systemic disease, there are some well-documented ALK+ve primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphomas. [2] Conversely, ALK negativity in skin does not necessarily exclude systemic disease, as 20-60% of systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma can be ALK-ve. [2] ALK expression correlates with young age, systemic disease, and usually good prognosis. [2]

About 40-65% of patients with anaplastic large cell lymphoma have extranodal disease either at the primary site or as part of the systemic process. [2] Determination of the origin of extranodal disease is critically important, particularly in the skin. EMA (MUC-1), frequently expressed in systemic anaplastic large cell lymphomas is associated with an inferior outcome in ALK−ve tumors. [3] In a study of 63 cases of systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma, George et al.[3] observed that ALK+ve lymphomas more frequently (73%) expressed EMA than ALK−ve lymphomas (49%) and the 5 year survival was 70.7% for patients with EMA+ve tumors and 93.8% for patients with EMA−ve tumors.They concluded that EMA expression conferred a poorer prognosis presumably because of resistance to chemotherapy. Our patient′s tumor was EMA positive, and even though her skin lesions responded to chemotherapy, her systemic disease was resistant to therapy.

Survivin, which inhibits apoptosis, is another independent prognostic marker in anaplastic large cell lymphoma. In ALK+ve tumors, when survivin is positive the 5-year survival is only 34% and when negative it increases to 100%. Similarly, in ALK-ve tumors, when survivin is positive, the 5-year survival is 46% and when negative it increases to 89%. [4]

ALK+ve patients respond better to CHOP regimen while EMA+ve patients respond poorly. The fatal outcome in our patient probably could be attributed to EMA+ve expression. Apart from chemotherapy, anti-CD 30 monoclonal antibodies have been used to treat systemic disease. In a study by Pro et al., [5] patients with relapsed/refractory anaplastic large cell lymphoma received anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody (brentuximab vedotin 1.8 mg/kg every 21 days, 16 cycles) as the second-line treatment. Tumor reduction was observed in 97% cases, while 57% achieved complete response. Our patient, a deserving candidate for this drug, could not receive it owing to its unavailability in India.

In our case, despite aggressive treatment with combination chemotherapy and local radiotherapy, the systemic lymphoma showed a negligible response. Positive EMA expression and generalized lymphadenopathy at the time of diagnosis were probable poor prognostic factors highlighting the difficulties encountered in managing aggressive disease in a resource-limited setting and the need for more promising treatment options like biologicals and immunotherapy.

| 1. |

Willemze R. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, editors. Dermatology. 3 rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012. p. 2029-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Campo E, Chott A, Kinney MC, Leoncini L, Meijer CJ, Papadimitriou CS, et al. Update on extranodal lymphomas. Conclusions of the Workshop held by the EAHP and the SH in Thessaloniki, Greece. Histopathology 2006;48:481-504.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

George R, Bhuvana S, Nair S, Lakshmanan J. Clinicopathological profile of cutaneous lymphomas-A 10 year retrospective study from south India. Indian J Cancer 1999;36:109-19.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Jacobsen E. Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma, T-/Null-Cell Type. Oncologist 2006;11:831-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Pro B, Advani R, Brice P. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2190-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,000

PDF downloads

1,374