Translate this page into:

Target and targetoid lesions in dermatology

Corresponding author: Dr. Geeti Khullar, Department of Dermatology, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, India. geetikhullar@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Bhandari M, Khullar G. Target and targetoid lesions in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:430-4.

Target lesions are characterized by a distinct clinical morphology, presenting as three concentric zones. They classically occur in erythema multiforme, an acute, self-limiting, often recurrent mucocutaneous disease involving mainly the face and extremities and most frequently related to infections, particularly herpes simplex virus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Targetoid lesions are target-like in appearance, with usually two concentric zones and are seen in several dermatologic conditions other than erythema multiforme. In 1993, Bastuji-Garin et al. proposed a classification system and defined two disease spectra – (1) erythema multiforme (major and minor) and (2) Stevens-Johnson syndrome – toxic epidermal necrolysis, the latter are usually drug induced and associated with high mortality.1 These diseases are classified based on the percentage of skin detachment and the pattern of individual target lesions.1 The various types of target lesions are as follows:

Typical targets: Round regular lesions with well-defined borders, <3 cm in diameter and having classic three zones – the inner most purpuric or necrotic with or without blister, the middle pale edematous ring, and the outer erythematous ring

Raised atypical targets: Round palpable edematous lesions that have two zones instead of three and/or an ill-defined border

Flat atypical targets: Round non-palpable lesions with two zones and/or a poorly defined border. Blister may be present in the center

Macules with or without blisters: Non-palpable erythematous macules of irregular size and shape with or without blisters.

Typical targets and raised atypical targets are seen in erythema multiforme, while flat atypical targets and macules with or without blisters are seen in Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome – toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap and toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 A minor modification of this classification has categorized typical targets as raised typical targets and flat typical targets. Taking this into consideration, raised typical and raised atypical targets are characteristic of erythema multiforme, while flat typical, flat atypical targets and macules with or without blisters are a feature of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.2

Erythema multiforme-like or targetoid lesions have been described in a wide range of other dermatoses [Table 1] which are briefly discussed below.

| Connective tissue disorder |

| Lupus erythematosus |

| Drug reactions |

| Stevens-Johnson syndrome – toxic epidermal necrolysis |

| Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms |

| Immunobullousdisorders |

| Bullous pemphigoid |

| Linear IgA bullous disease |

| Pemphigoid gestationis |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus |

| Infections |

| COVID-19 |

| Erythema chronicum migrans |

| Erythema nodosum leprosum |

| Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis |

| Syphilis |

| Inflammatory disorders |

| Erythema multiforme |

| Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy |

| Erythema multiforme-like allergic contact dermatitis |

| Pityriasis rosea |

| Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy |

| Sweet’s syndrome |

| Urticaria multiforme |

| Tumor |

| Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma |

Connective Tissue Disorder

Lupus erythematosus

The occurrence of erythema multiforme-like lesions in lupus erythematosus, either systemic or cutaneous, is described as Rowell syndrome. It was first studied in 1963 in four women with discoid lupus erythematous, chilblain lupus, and lesions resembling erythema multiforme. Laboratory investigations revealed speckled pattern of antinuclear antibody, positive rheumatoid factor, positive anti-La, and pancytopenia.3 Subsequently, in a review of 95 cases, erythema multiforme-like lesions associated with lupus erythematosus were grouped into two subtypes4 – the first being subacute cutaneous/acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus with erythema multiforme-like lesions, in which there is no preferential location, mucous membranes are uncommonly involved, and triggering factor is identified occasionally but is never herpes simplex virus. On direct immunofluorescence, pattern of lupus erythematosus-specific lesions is observed in majority of the cases. Erythema multiforme-like lesions in this setting are regarded as morphologic variants of lupus erythematosus-specific skin lesions [Figure 1]. The second group comprises chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus with erythema multiforme-like lesions, in which the clinical and immunological features resemble those originally described by Rowell et al. and hence some authors have reserved the term “Rowell syndrome” for this subset of patients.

- Raised typical and atypical target lesions in a patient of systemic lupus erythematosus

Drug Reaction

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

Atypical purpuric target lesions not necessarily confined to acral sites are associated with severe systemic involvement in the form of serious liver dysfunction and increased mortality.5

Immunobullous Disorders

Bullous pemphigoid

Targetoid lesions along with widespread bullous lesions have been described in erythema multiforme-like bullous pemphigoid. Severe involvement of mucosae reminiscent of erythema multiforme major can be associated. Majority of these cases were classified as drug-induced erythema multiforme-like bullous pemphigoid and the drugs implicated were penicillins and furosemide.6

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis

Varied presentations can occur in adults, resembling bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, erythema multiforme, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Erythema multiforme and toxic epidermal necrolysis-like presentation with widespread bullae are seen in drug-induced cases, with vancomycin being the most common drug followed by phenytoin and lithium.7 The lesions present as flat targetoid macules with a central bulla [Figure 2].

- Erythematous plaques showing central vesiculation and crusting along with tense bullae on the back in linear IgA bullous dermatosis

Pemphigoid gestationis

Clinical manifestations include tense bullae, herpetiform vesicles, and urticarial and targetoid plaques, usually involving the periumbilical area.8 Although the lesions typically develop during late pregnancy, they can sometimes occur in early pregnancy and immediate postpartum period.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus

The earliest and the most consistent finding is severe mucositis. Although oral erosions can affect any site, they characteristically involve the vermilion of the lips and resemble erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. The cutaneous lesions are polymorphic and resemble those of pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, lichen planus, erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and graft versus host disease, depending on whether humoral or cytotoxic immunity is predominant. Erythema multiforme-like cutaneous lesions, extensive skin/ mucosal involvement, and keratinocyte necrosis on histology are linked to more severe disease and shorter survival rate.9

Infections

COVID-19

In a case series of four patients with erythema multiforme-like eruption, the sites involved were face, trunk, and limbs, with sparing of palms and soles. Two patients had typical target lesions. Oral mucosa showed palatal macules and petechiae.10 All patients developed the lesions after the onset of coronavirus symptoms, with a mean interval of 19.5 days. The onset of erythema multiforme-like lesions was associated with worsening of one or more laboratory parameters (C-reactive protein, D-dimer, or lymphocyte count), but no recurrence of coronavirus symptoms.10

Erythema chronicum migrans

It develops 3–30 days after tick bite as an expanding round to oval, larger than 5 cm in size, erythematous lesion with a slightly dusky center indicating the site of bite.11 After a few weeks, the center fades leaving behind an erythematous border. It has a predilection for lower limbs, axillary and inguinal areas in adults, and face in children.

Erythema nodosum leprosum

Erythema multiforme-like erythema nodosum leprosum has been described in around 4.5% of leprosy patients.12 Concomitant lesions of classic erythema nodosum leprosum may be seen in some cases. Palmoplantar lesions and mucosal involvement are not observed. Histologically, subepidermal edema, occasionally bulla, and few apoptotic keratinocytes are described.12,13

Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis

M.pneumoniae associated mucocutaneous eruption consists of severe mucositis with sparse cutaneous involvement. The cutaneous lesions are polymorphic, with vesiculobullous being the most common (77%), followed by targetoid lesions (48%), macules, papules, morbilliform rash, and rarely toxic epidermal necrolysis-like presentation.14 Targetoid lesions are often atypical flat purpuric macules, centrally distributed and associated with respiratory tract sequelae.15 Serologic testing and polymerase chain reaction from throat swab confirm the diagnosis.

Syphilis

Erythema multiforme-like morphology has been reported in secondary and congenital syphilis.7,16 The skin biopsy shows findings of erythema multiforme with or without plasma cells. Treponema pallidum has been demonstrated by immunoperoxidase staining and polymerase chain reaction in these lesions. It is hypothesized to occur due to direct spirochete invasion provoking specific immune response against T.pallidum.7,16 In contrast, erythema multiforme triggered by syphilis shows mixed inflammatory infiltrate with the absence of treponemes.

Inflammatory Disorders

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy

It is a self-limiting form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis that affects children between four months and two years of age. It presents with mild fever, peripheral non-pitting edema, and skin lesions, which start as macules, papules, and urticarial plaques and later evolves into cockade or targetoid purpuric lesions on the face, auricles, and extremities [Figures 3a and b]. Systemic involvement is uncommon.2,7

- Ill to well-defined targetoid plaques with central purpuric area surrounded by an edematous erythematous zone on the extensor aspect of the lower limb

- Targetoid plaques on the cheeks with associated edema of the left auricle

Erythema multiforme-like allergic contact dermatitis

It is caused by plants such as Primula, Toxicodendron (poison ivy), Compositae, and quinones in exotic woods. Other allergens include medicaments such as triamcinolone acetonide, neomycin, bufexamac, and miscellaneous compounds such as paraphenylenediamine, clothing dyes, and rubber chemicals.17 The lesions may be limited to the site of contact or become generalized in case of systemic exposure to a topically sensitized compound.

Pityriasis rosea

Erythema multiforme-like pityriasis rosea is an uncommon atypical morphological variant. The lesions may occur along with typical papulosquamous lesions in a Christmas tree pattern. It could also represent erythema multiforme in response to human herpes virus-6 and 7. Histopathology shows findings of pityriasis rosea with the absence of vacuolar degeneration and satellite cell necrosis. In a series of 40 cases of pityriasis rosea, four were reported to have erythema multiforme-like morphology.18

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy

In a study of 181 patients, 51% developed features such as eczematous lesions (22%), vesicles (17%), non-urticarial erythema (6%), and targetoid lesions (6%), in addition to the classic pruritic urticarial papules and plaques.19

Sweet’s syndrome

In a study of 90 patients, atypical targetoid lesions were reported along with the classic lesions in 11 cases. Significant correlation was observed between targetoid lesions and vasculitis on histological examination.20

Urticaria multiforme

It is an acute cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction, which presents in children as blanchable, annular, and polycyclic erythematous wheals with a dusky ecchymotic center [Figure 4]. However, true target lesions, skin necrosis, or blistering are not seen. It is associated with angioedema of face, hands, feet, and dermographism and resolves within 24 h.7

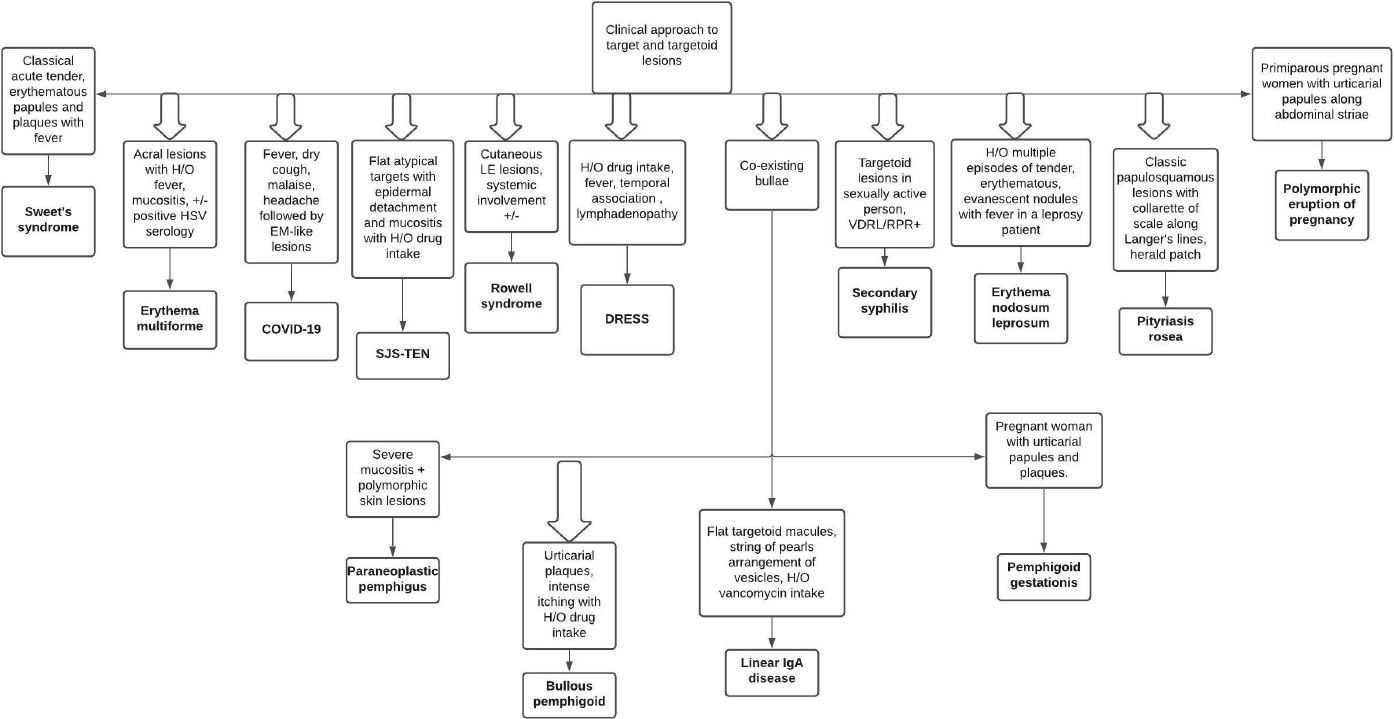

- Flowchart showing clinical approach to targetoid lesions

Tumor

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma

It is a benign vascular tumor which exhibits a violaceous papule in the center surrounded by a pale area and an ecchymotic ring at the periphery.2

Approach to target and targetoid lesions

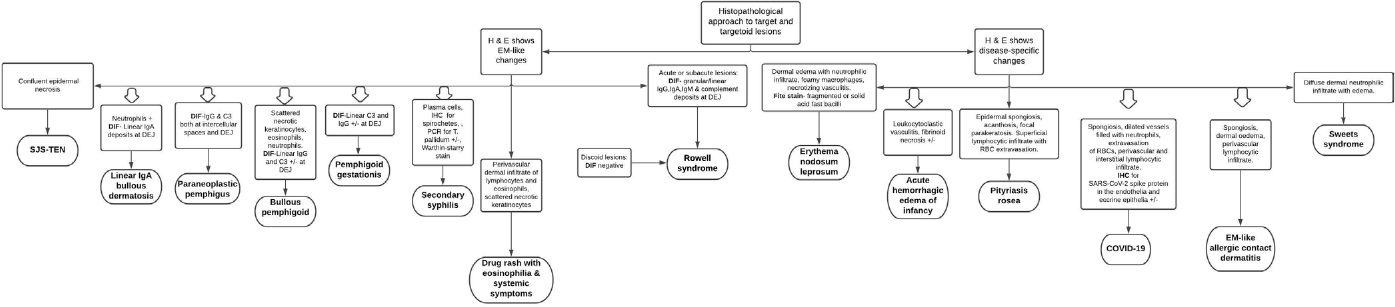

As the list of differential diagnoses for a patient presenting with targetoid lesions is quite extensive, a detailed history, clinical examination, and guided laboratory investigations including skin biopsy, direct immunofluorescence, serological, and other relevant tests are imperative in reaching a definitive diagnosis. A step-wise systematic approach to targetoid lesions, based on history, clinical presentation, and histopathological examination is depicted in Figures 4 and 5.

- Flowchart depicting histopathological approach to targetoid lesions

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shape and configuration of skin lesions: Targetoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:504-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupus erythematosus and erythema multiforme-like lesions. A syndrome with characteristic immunological abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:176-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:417-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: Is cutaneous phenotype a prognostic marker for outcome? A review of clinicopathological features of 27 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:391-401.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atypical presentations of bullous pemphigoid: Clinical and immunopathological aspects. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:438-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The rash that presents as target lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:148-58.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesicles and targetoid lesions in a postpartum woman. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:445-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic factors of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1165-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erythema multiforme-like eruption in patients with COVID-19 infection: Clinical and histological findings. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:892-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyme disease in Haryana, India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:320-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erythema multiforme in leprosy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107(Suppl 1):34-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A retrospective study of the severe and uncommon variants of erythema nodosum leprosum at a tertiary health center in Central India. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2019;8:29-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and histologic features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-related erythema multiforme: A single-center series of 33 cases compared with 100 cases induced by other causes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:110-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secondary syphilis presenting as erythema multiforme in a HIV-positive homosexual man: A case report and literature review. Int J STD AIDS. 2019;30:304-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noneczematous contact dermatitis. ISRN Allergy. 2013;2013:361746.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pityriasis rosea with erythema multiforme-like lesions: An observational analysis. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:242.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: Clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:54-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet's syndrome: A retrospective study of 90 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1033-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]