Translate this page into:

Tattoo inoculation lupus vulgaris in two brothers

2 Department of Pathology, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, University of Delhi, Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Deepika Pandhi

B-1/1101, Vasant Kunj, Delhi - 110 070

India

| How to cite this article: Dhawan AK, Pandhi D, Wadhwa N, Singal A. Tattoo inoculation lupus vulgaris in two brothers. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2015;81:516-518 |

Sir,

Tattooing is widely prevalent among various races across the world for ornamental, religious and traditional purposes. [1] There is an increased trend of tattooing among the young population that puts them at risk for many infective and noninfective disorders. [2] We report an uncommon occurrence of tattoo inoculated cutaneous tuberculosis presenting as lupus vulgaris in two siblings who responded to standard antitubercular therapy.

Two brothers aged 15 (Case 1) and 12 years (Case 2) presented to the dermatology outpatient department of Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, with complaints of skin lesions at the tattoo site for 2 months. Both had been tattoed around 5 months back at a religious fair at the same sitting with the same needle and ink. After 3 months, both developed scaling and painless thickening at the tattoo site which gradually progressed beyond the tattoo margin. There were no other significant complaints in either of them or in any other family members.

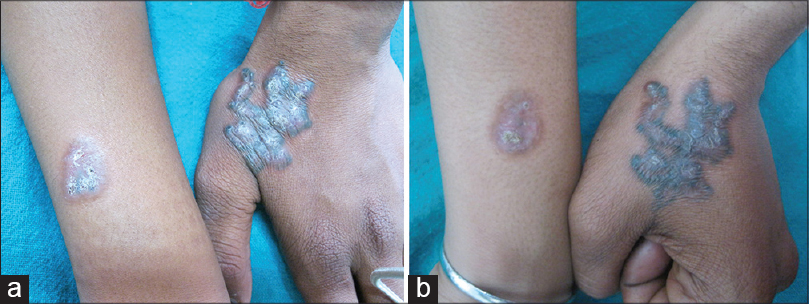

On examination of Case 1, a single erythematous plaque measuring 7.2 × 5.1 cm involving the tattoo over the dorso-lateral aspect of left hand was seen. The centre of the plaque showed atrophy and minimal scaling [Figure - 1]a. There were no other abnormalities on examination.

|

| Figure 1: (a) Erythematous plaques with atrophy and scaling over the tattoo in the shape of a religious symbol (Trishul) and the letter A in two brothers. (b) Lesion healed with scarring and residual tattoo pigment in both siblings after 6 months of anti-tubercular treatment |

Examination of Case 2 revealed a single erythematous plaque present over the dorso-lateral aspect of right forearm measuring 2.5 × 1.5 cm. The plaque surface extended beyond the A shaped tattoo and showed atrophy [Figure - 1]a. He also had significant epitrochlear and axiliary lymphadenopathy that on fine needle aspiration cytology showed reactive changes. His systemic examination was unremarkable.

We considered the possibilities of tattoo inoculated lupus vulgaris, subcutaneous mycosis, borderline tuberculoid leprosy, tattoo sarcoid and granulomatous dermatitis. In both brothers, the chest X-rays, ultrasonography of the abdomen and hematological investigations were unremarkable except for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B antigen and hepatitis C antibodies were also negative. The Mantoux test revealed an induration of 15 and 18 mm after 2 days in Case 1 and 2, respectively.

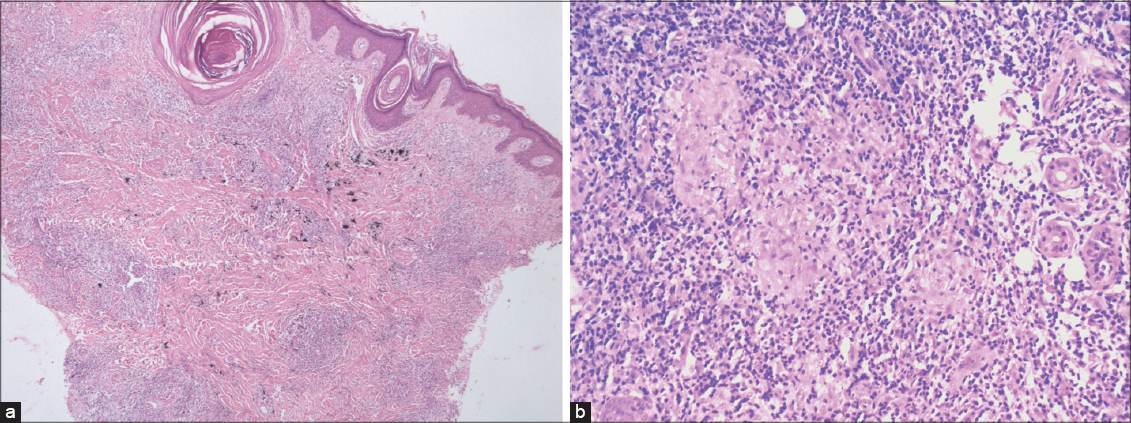

Skin biopsy from both cases revealed similar findings: hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, a dense inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly of mononuclear cells present throughout the dermis and foci of granulomatous infiltrate [Figure - 2]a and b. There was also evidence of secondary granulomatous vasculitis and exogenous pigment consistent with tattoo. Examination of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), silver nitrate and Fite-faraco stained slides failed to reveal any organisms. In Case 2, tissue sent for mycobacterial culture grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for 173 bp of mycobacteria. Culture for fungus and atypical mycobacteria were negative in both cases.

|

| Figure 2: (a) Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, with dense pandermal mononuclear infiltrate (H and E, ×40). (b) Epithelioid cell granuloma adjacent to a sweat duct (H and E, ×400) |

Anti-tubercular therapy comprising rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide for the first 2 months followed by rifampicin and isoniazid for 4 months was instituted in both cases, and clinical improvement with scarring and residual tattoo pigment was evident at 6 months [Figure - 1]b.

Tattooing exposes an individual to various infective and non-infective dermatoses. The infective disorders associated with tattooing include viral warts, syphilis, leprosy, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, molluscum contagiosum and those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).[1],[2],[3],[4] Inoculation tuberculosis has been reported with various practices like piercing, sharing of infected syringes or needles, sexual intercourse, venepuncture, tooth extraction and tattooing. [4],[5],[6] The factors implicated in the pathogenesis of tattoo inoculation tuberculosis include disruption of the skin barrier and unhygienic practices like sharing the same needle and ink and dilution of ink with tap water or saliva harboring mycobacteria. [5],[6] Tattoo inoculation lupus vulgaris is uncommon and there are only a few previous reports of the condition. [4],[5],[6] Ghorpade reported three cases of cutaneous tuberculosis that presented 4-12 months after tattooing wherein the patients developed multiple papules and plaques overlying and extending beyond the tattoo site. [5] Recently, cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections caused by Mycobacterium haemophilum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium fortuitum at the tattoo site have been reported. [7],[8],[9] Several non-tuberculous mycobacterial species such as Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium chelonae are usually present in tap water and dilution of ink with tap water may lead to contamination and subsequent infection. [8]

The diagnosis of lupus vulgaris is made on clinical and histopathological grounds. However, in the present case, the tattoo evoked a dense inflammatory reaction comprising of histiocytes, lymphocytes and a few plasma cells and eosinophils which masked the granulomas. The positive mycobacterial culture and molecular evidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the lesion (by PCR) and clinical response to anti-tubercular treatment substantiated the histological diagnosis.

The occurrence of lupus vulgaris at the site of tattoo in both siblings suggests inoculation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during the same tattoo session. Though desirable, it was not feasible for us to culture the causative organism from the tattooing ink bottle and equipment and to screen the tattoo artist for active infection.

| 1. |

LeBlanc PM, Hollinger KA, Klontz KC. Tattoo ink-related infections--awareness, diagnosis, reporting, and prevention. N Engl J Med 2012;367:985-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Jacob CI. Tattoo-associated dermatoses: A case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:962-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Molina L, Romiti R. Molluscum contagiosum on tattoo. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:352-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Horney DA, Gaither JM, Lauer R, Norins AL, Mathur PN. Cutaneous inoculation tuberculosis secondary to ′jailhouse tattooing′ . Arch Dermatol 1985;121:648-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Ghorpade A. Tattoo inoculation lupus vulgaris in two Indian ladies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:476-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Wong HW, Tay YK, Sim CS. Papular eruption on a tattoo: A case of primary inoculation tuberculosis. Australas J Dermatol 2005;46:84-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Tattoo-associated nontuberculous mycobacterial skin infections--multiple states, 2011-2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:653-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Giulieri S, Cavassini M, Jaton K. Mycobacterium chelonae illnesses associated with tattoo ink. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2357.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Philips RC, Hunter-Ellul LA, Martin JE, Wilkerson MG. Mycobacterium fortuitum infection arising in a new tattoo. Dermatol Online J 2014:15:20.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,133

PDF downloads

864