Translate this page into:

The optimal dose of oral tranexamic acid in melasma: A network meta-analysis

Corresponding author: Dr. Tai-Yin Wu, No.145, Zhengzhou Road, Datong District, Taipei City, Taiwan. taiyinwu@ntu.edu.tw

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Wang W-J, Wu T-Y, Tu Y-K, Kuo K-L, Tsai C-Y, Chie W-C. The optimal dose of oral tranexamic acid in melasma: A network meta-analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023;89:189-94.

Abstract

Background:

Melasma is a chronic skin condition that adversely impacts quality of life. Although many therapeutic modalities are available there is no single best treatment for melasma. Oral tranexamic acid has been used for the treatment of this condition but its optimal dose is yet to be established.

Objectives:

We used network meta-analysis to determine the optimal dose of oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma.

Methods:

We conducted a comprehensive search of all studies of oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma up to September 2020 using PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library database. The quality of the studies was evaluated using the Jadad score and the Cochrane’s risk of bias assessment tool. Only high quality randomised controlled trials were selected. Some studies lacked standard deviation of changes from baseline and these were estimated using the correlation coefficient obtained from another similar study.

Results:

A total of 92 studies were identified of which 6 randomized controlled trials comprising 599 patients were included to form 3 pair-wise network comparisons. The mean age of the patients in these studies ranged from 30.3 to 46.5 years and the treatment duration ranged from 8 to 12 weeks. The Jadad scores ranged from 5 to 8.

The optimal dose and duration of oral tranexamic acid was estimated to be 750 mg per day for 12 consecutive weeks.

Limitations:

Some confounding factors might not have been described in the original studies. Although clear rules were followed, the Melasma Area and Severity Index and the modified Melasma Area and Severity Index were scored by independent physicians and hence inter-observer bias could not be excluded.

Conclusion:

Oral tranexamic acid is a promising drug for the treatment of melasma. This is the first network meta-analysis to determine the optimal dose of this drug and to report the effects of different dosages. The optimal dose is 250 mg three times per day for 12 weeks, but 250 mg twice daily may be an acceptable option in poorly adherent patients. Our findings will allow physicians to balance drug effects and medication adherence. Personalized treatment plans are warranted.

Keywords

Oral tranexamic acid

melasma

network meta-analysis

Plain Language Summary

Melasma is a common chronic and relapsing disorder of skin pigmentation, affecting 1% of people in the general population. It distresses patients psychosocially and emotionally and reduces their quality of life. Treating melasma is challenging because current treatment options cannot promise satisfied results. The gold standard treatment can also bring unwanted adverse effects. Oral tranexamic acid is a promising way to treat melasma, owing to the convenience and safety of use. However, there was no single large study to conclude the optimal dosage of oral tranexamic acid. Network meta-analysis is an advanced statistical method to investigate the effects of different interventions, even when the interventions are not compared to each other directly.

The authors conducted a comprehensive search of studies up to September 2020 using several medical databases. After accessing the qualities of 92 identified studies, six studies, from Asia and South America, were included in the statistical analysis. By using network meta-analysis, the authors found that the optimal dose and treatment duration of oral tranexamic acid is 750mg per day in three divided doses for 12 consecutive weeks. The results also revealed the effects of different dosages. The authors believe this study could benefit daily practice when treating melasma.

Introduction

Melasma is a common chronic, relapsing disorder of skin pigmentation affecting the epidermis and dermis. It presents as irregular light to dark brown patches on the face, especially on the malar area.1 Although the prevalence of melasma in the general population is about 1%, in some predisposed groups (eg., pregnancy, darker skin types) it may be higher at 9.0– 50.0%.2 Melasma can distress patients psychosocially and emotionally and thus negatively impact the quality of life.3

The aetiology of melasma is unclear, but multiple trigger factors including ultraviolet exposure, genetic factors, hormonal changes, skin inflammation, pregnancy and stressful events have been identified.1,4–6 Oral contraceptive pills, hormone replacement therapy, cosmetics and photosensitising drugs may also precipitate melasma. Increased vascularity and mast cells in the dermis may also play a role in the pathogenesis of melasma.7,8

Treatment of melasma is challenging as current treatment options are unsatisfactory.3 Daily broad-spectrum photoprotection and topical hydroquinone have been the mainstay of therapy.9 However, there is a risk of contact dermatitis, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and exogenous ochronosis with hydroquinone.3,10 Second-line therapies include topical bleaching agents, chemical peels, and laser or light-based therapies.10–12

The use of oral tranexamic acid for melasma was first described in 1979 in Japan.13 Other routes (topical, intralesional, iontophoresis, intravenous) of administration of tranexamic acid have also been studied.14 Two mechanisms explain the hypopigmentary effect of tranexamic acid. Ultraviolet light provokes plasmin activity in keratinocytes and activates melanin synthesis. Tranexamic acid inhibits plasmin activity and thus reduces melanin synthesis. Further, part of the tranexamic acid structure resembles tyrosine and hence it may competitively inhibit tyrosinase.15–17

Oral tranexamic acid is safe and convenient to use. The most common side effects are gastrointestinal irritation and hypomenorrhea.18 Contraindications to its use include coagulation disorders, thromboembolic disease and severe renal insufficiency and patients should be screened to evaluate these risk factors prior to starting therapy.19,20 However, potentially life-threatening side effects, such as acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, are rare while using oral tranexamic acid for melasma as the dosages are much lower than that used for coagulation disorders.18

Although there are many clinical trials demonstrating the effectiveness of tranexamic acid (oral, topical or intralesional, compared to placebo or hydroquinone) in the treatment of melasma, no large randomized controlled trials or interracial studies have been conducted. There is also no consensus on the optimal dosage of oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma.20–28

Network meta-analysis can help in decision-making by comparing the effectiveness of the different interventions even when lacking sufficient head-to-head comparisons.29,30 We aimed to utilize network meta-analysis to find the ideal dose of oral tranexamic acid for treating melasma.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched studies published from 1950 to September 2020 in the MEDLINE and EMBASE electronic databases using “oral tranexamic acid,” “melasma” and “chloasma” as keywords. The search was restricted to articles in the English language only. The reference lists of the retrieved articles for eligible studies were reviewed. The terms used with Boolean logic were (oral tranexamic acid) AND ((melasma) OR (chloasma)) and restricted to articles that contained these terms in their title or abstract. The variables sought were all possible dosages and the duration of treatment with tranexamic acid.

The Cochrane Library was also searched for comprehensiveness to see if there had been other meta-analysis of oral tranexamic acid in melasma.

Study selection

The criteria for qualitative and quantitative analysis of the retrieved studies included

Random allocation of patients to different treatments

Studies involving oral tranexamic acid

Use of Melasma Area and Severity Index or modified Melasma Area and Severity Index as the standard tool to evaluate melasma severity

Studies were excluded if

They were non-human studies (in vivo or in vitro)

They involved skin diseases other than melisma

If their initial Melasma Area and Severity Index/modified Melasma Area and Severity Index differed widely (>5) within the two arms or

If they did not provide adequate data that was crucial to network meta-analysis (e.g. not providing standard deviation).

Data extraction and quality assessment

All related systematic reviews and reference lists of the retrieved studies were evaluated for other potentially qualified studies. Two authors (Wang WJ, Wu TY) independently reviewed all included articles and extracted the data from the studies. The quality of the studies was assessed using the Jadad score.31 Higher scores represented better methodological quality. The risk of bias was evaluated for methodological flaws using Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of the bias assessment tool.32 Any discrepancy between the two reviewers was discussed and resolved.

Statistical analysis

As the severity of melasma differed among studies, a random effects model was used to calculate the pooled mean difference along with a 95% confidence interval for the association between oral tranexamic acid and improvement of Melasma Area and Severity Index. This model was chosen as the number of included studies was more than five and also because we intended to generalize the results beyond the enrolled studies.33

The consistency H value was used to evaluate the inconsistency of treatment effects. The minimum value of H is 1 and values <3 represent minimal inconsistency, values between 3 and 6 suggest modest network inconsistency and >6 indicates network inconsistency. If inconsistency was minimal or modest, the results is reliable.34

Some studies lacked the standard deviation of changes from baseline. In these, the data were obtained by calculating the standard deviation and correlation coefficient before and after treatment.35,36 As none of the included studies could provide complete data to calculate correlation coefficient, this was obtained from a similar study comparing oral tranexamic acid and hydroquinone for their effect in treating melasma.37 Network meta-analysis was conducted on the MetaXL 5.3 program (EpiGear International Pty Ltd., Wilston, Queensland, Australia) and MetaInsight (https://crsu.shinyapps.io/metainsightc).38

Results

Studies included in the meta-analysis

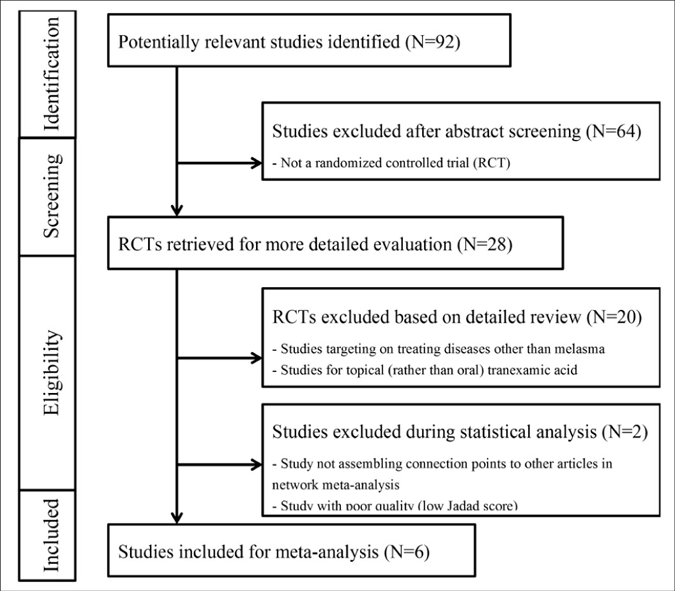

After excluding non-randomised controlled trials studies and duplicate studies, a total of 28 studies were identified of which 8 randomised controlled trials were selected after reviewing the title and abstract details. One of these 8 studies was excluded as the quality of the study was poor (score of 3 in the Jadad scoring system)24 and another study was discarded at the end of our analysis as we were unable to assemble the connection points to other articles and was thus could not form a valid network.39 The flowchart of study selection is presented in Figure 1.

- Flowchart of study selection. MASI: Melasma Area and Severity Index

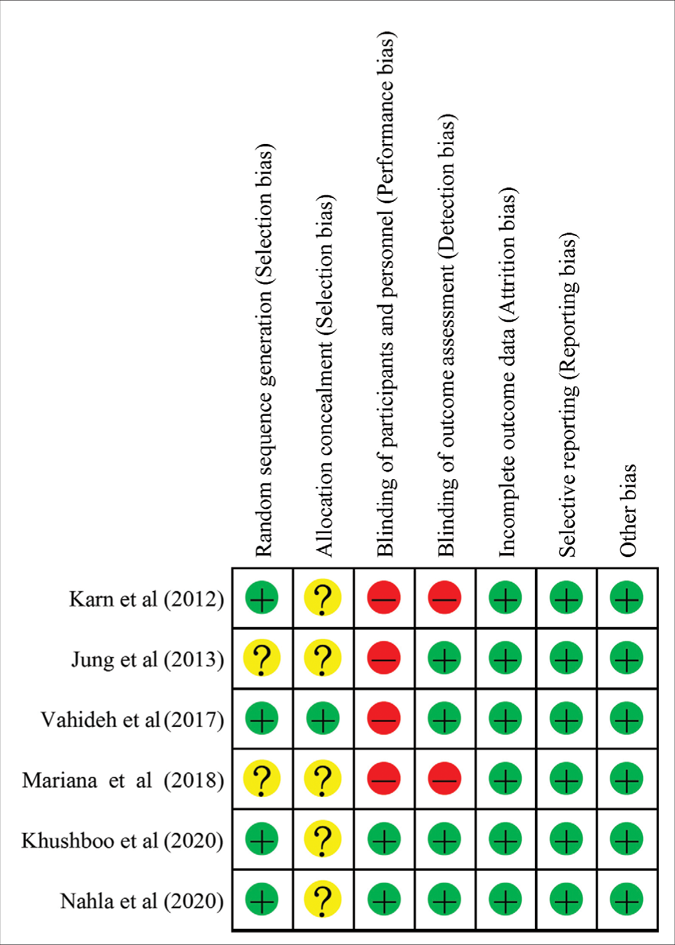

Thus, 6 randomised controlled trials including 599 patients met the inclusion criteria. The relevant features of the included studies are presented in Table 1.27,40-44 The mean ages of the patients were 30.3–46.5 years. The treatment duration ranged from 8 to 12 weeks. The Jadad scores of the studies ranged from 5 to 8, indicating that they were of adequate quality. The results of the 7 domains of risk of bias assessed for each study are presented in Figure 2. The risk of bias across studies was low because most data were from randomised controlled trials.

| Author (publish year) | Journal | Age (mean ± SD) | Treatment arm 1 (patient number) | Treatment arm 2 (patient number) | Treatment duration (weeks) |

Outcome measure ment |

Recruiting area |

Jadad scores |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karn et al. (2012)39 | Kathmandu University Medical Journal |

30.3 ± 9.0 | oral TA 500mg/day (130) | Placebo (130) | 12 | MASI* | Nepal | 6 | ||

| Jung et al. (2013)27 | Dermatologic Surgery |

43.8 ± 7.4 | oral TA 750mg/day (23) | Placebo (21) | 8 | mMASI$ | Korea | 5 | ||

| Vahideh et al. (2017)40 | Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology |

36.3 ± 5.8 | oral TA 750mg/day (45) | Placebo (43) | 12 | MASI | Iran | 7.5 | ||

| Mariana et al. (2018)41 | Journal of Cosmetic Denna- tology |

44.4 ± N/A | oral TA 500mg/day (20) | Placebo (17) | 12 | MASI | Brazil | 7 | ||

| Khushboo et al. (2020)42 | Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology | 37.25 ± N/A oral TA 500mg/day (61) | Placebo (59) | 12 | mMASI | India | 8 | |||

| Nahla et al. (2020)43 | Australasian Journal of Dermatology |

46.5 ± 5.6 | oral TA 500mg/day (25) | Placebo (25) | 12 | mMASI | Indonesia | 8 | ||

- Risk of bias summary for each included study. Minus sign represents high risk of bias. Plus sign means low risk of bias. Question mark sign means unclear risk of bias

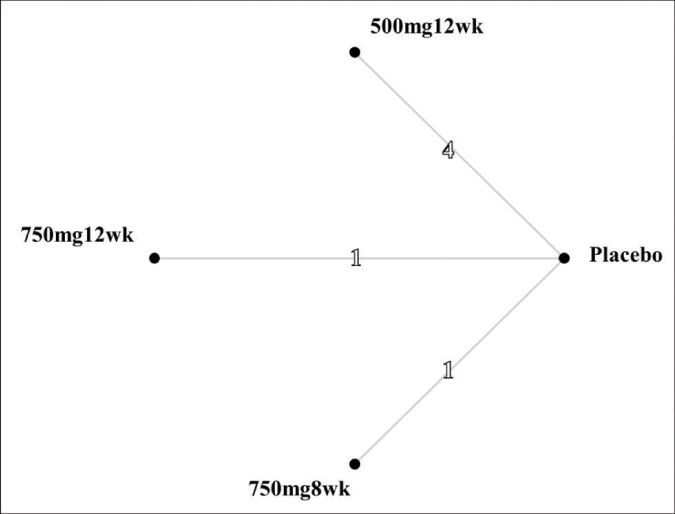

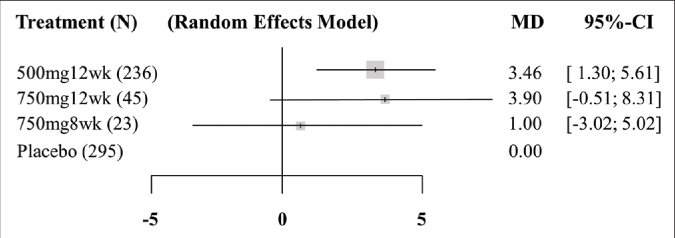

Three pair-wise comparisons were performed, forming the network [Figure 3]. The summary mean difference with 95% confidence interval is shown in Figure 4. The mean difference between tranexamic acid 750 mg and placebo for 8 weeks was 1.0 (confidence intervals –3.02, –5.02). For the other two groups (tranexamic acid 500 mg for 12 weeks and tranexamic acid 750 mg for 12 weeks), the mean difference was 3.46 (confidence intervals -1.30, –5.61) and 3.90 (confidence intervals –0.51, –8.31), respectively. The best results according to the Melasma Area and Severity Index/modified Melasma Area and Severity Index scores were with oral tranexamic acid 750 mg per day for 12 weeks. The consistency H value was 1.0, indicating minimal inconsistency of treatment effects.34

- Network structure. The numbers on the lines represent the cumulative numbers of studies for each comparison. 500mg12wk: taking oral tranexamic acid 50 mg per day for 12 weeks. 750mg12wk: taking oral tranexamic acid 750 mg per day for 12 weeks. 750mg8wk: taking oral tranexamic acid 750 mg per day for 8 weeks

- Forest plot of the network meta-analysis. 500mg12wk: taking oral tranexamic acid 500 mg per day for 12 weeks. 750mg12wk: taking oral tranexamic acid 750 mg per day for 12 weeks. 750mg8wk: taking oral tranexamic acid 750 mg per day for 8 weeks. N: sample size. MD: mean difference, mean effect size. CI: confidence interval. Weight was proportional to sample size. The consistency H value was 1.0

A league table of the efficacy of different doses and delivery systems in treating melasma is shown in Table 2. Odds ratios below 1 favors the lower-right treatment. Besides finding that oral tranexamic acid 750 mg per day for 12 weeks yielded the best result, we also observed the contrast between the other groups. In the indirect comparison, taking oral tranexamic acid 500 mg per day for 12 weeks was superior to oral tranexamic acid 750 mg per day for 8 weeks.

| Placebo | −1.00 (−5.02~3.02) | −3.46 (−5.61~ −1.30) | −3.90 (−8.31~0.51) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1.00 (−5.02~3.02) −3.46 (−5.61~ −1.30) |

750mg8wk −2.46 (−7.02~2.11) |

500mg12wk | |

| −3.90 (−8.31~0.51) | −2.90 (−8.87~3.07) | −0.44 (−5.35~4.46) | 750mg12wk |

The results of mean difference, obtained from pairwise meta-analysis, are presented in the upper-right cells. The results of mean difference, obtained from network meta-analysis (NMA), are showed in the lower-left cells. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confident intervals of comparisons between treatments are shown in the cells. Odds ratios less than one favor the lower-right treatment.

Discussion

There is no single best treatment for melasma. The risk of contact dermatitis and exogenous ochronosis with hydroquinone and confetti-like hypopigmentation with laser therapy are real.45 The low risk of adverse effects with oral tranexamic acid makes it a plausible treatment option for melasma.46 An analysis of the effect of different doses of oral tranexamic acid on melasma did not demonstrate an increase in side effects with doses up to 1500 mg/day.39

This is the first network meta-analysis investigating the optimal dose of oral tranexamic acid in treating melasma. The use of network meta-analysis overcomes the problem of the paucity of large randomised controlled trials.

In this study, a dose of 750 mg per day of oral tranexamic acid for 12 consecutive weeks was found to be the optimal dose and duration to treat melasma. It was also noted that the effect of oral tranexamic acid 250 mg twice daily and three times daily over 12 weeks were similar. Further, oral tranexamic acid 500 mg per day for 12 weeks had a better outcome than tranexamic acid 750 mg per day for 8 weeks, which implies that the duration of therapy may have been more important than the total daily dosage. It would be of interest to investigate in future studies whether treatment durations longer than 12 weeks show better outcomes. It has been demonstrated that medication adherence drops significantly after six months, so keeping the duration of treatment shorter than this is a good strategy.47

The strengths of this study are many, including the fact that this is the first to report the optimal dose of oral tranexamic acid in melasma. Further, this is an interracial study and is thus generalisable. The inclusion of only high-quality randomised controlled trials with good consistency reduced the risk of bias but the paucity of such trials made it more difficult to come to a reliable conclusion.

The limitations of this study include the fact that the software we used could not generate the surface under the cumulative ranking curve and rankogram. Further, some confounding factors might not have been described in the original studies. Although clear rules were followed for scoring the Melasma Area and Severity Index and modified Melasma Area and Severity Index, they were scored by independent physicians and hence inter-observer bias cannot be excluded.

The results of our study impacts clinical decision making allowing physicians to balance the drug effects and medication adherence. Personalised treatment plans for patients can hence be realised.

Further studies including more up-to-date randomised controlled trials to expand this network meta-analysis and compare the dose-effect to other treatment regimens of melasma (such as hydroquinone) should be conducted in future.

Conclusion

Oral tranexamic acid is a promising drug for melasma. The optimal dose of this drug is 250 mg three times per day for 12 consecutive weeks, but 250 mg twice daily may be an acceptable option in poorly adherent patients.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required as the patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Melasma: An up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:305-18.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melasma: a comprehensive update: Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:689-97.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physiological changes in the skin during pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:35-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical patterns and epidemiological characteristics of facial melasma in Brazilian women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:151-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent progress in melasma pathogenesis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28:648-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heterogeneous pathology of melasma and its clinical implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:824.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melasma pathogenesis and influencing factors-An overview of the latest research. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(Suppl 1):5-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of hyperpigmentation in darker racial ethnic groups. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:77-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melasma: A comprehensive update: Part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:699-714.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melasma: Clinical diagnosis and management options. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:151-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-based treatment for melasma: Expert opinion and a review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2014;4:165-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranexamic acid: An important adjuvant in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:57-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of the inhibitory effect of tranexamic acid on melanogenesis in cultured human melanocytes in the presence of keratinocyte-conditioned medium. J Health Sci. 2007;53:389-96.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tranexamic acid can treat ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation in guinea pigs. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:289-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topical trans-4-aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid prevents ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;47:136-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plasminogen regulates pro-opiomelanocortin processing. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:785-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: A comprehensive review of clinical studies. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: A review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral tranexamic acid (TA) in the treatment of melasma: A retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:385-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of tranexamic acid on melasma: A clinical trial with histological evaluation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1035-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of melasma with oral administration of tranexamic acid. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36:964-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral tranexamic acid lightens refractory melasma. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e105-e8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral tranexamic acid with fluocinolone-based triple combination cream versus fluocinolone-based triple combination cream alone in melasma: An open labeled randomized comparative trial. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of oral tranexamic acid in melasma patients treated with IPL and low fluence QS Nd:YAG laser. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:292-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of melasma with oral administration of compound tranexamic acid: A preliminary clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol2014;. ;28:393-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral tranexamic acid enhances the efficacy of low-fluence 1064-nm quality-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser treatment for melasma in Koreans: A randomized, prospective trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:435-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Localized intradermal microinjection of tranexamic acid for treatment of melasma in Asian patients: A preliminary clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:626-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: Combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ. 2005;331:897-900.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network meta-analysis for comparing treatment effects of multiple interventions: An introduction. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34:1489-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixed or random effects meta-analysis? Common methodological issues in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:196-207.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A generalized pairwise modelling framework for network meta-analysis. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2018;16:187-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:769-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meta-analysis of heterogeneously reported trials assessing change from baseline. Stat Med. 2005;24:3823-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of efficacy and safety of topical hydroquinone 2% and oral tranexamic acid 500 mg in patients of melasma. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2018;27:204-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- MetaXL User Guide Australia: EpiGear International Pty Ltd. 2011. version 5.3. [cited 2020 Oct 3]. [Available from: http://www.epigear.com/index_files/MetaXL%20User%20Guide.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the effect of different doses of oral tranexamic acid on melasma: A multicentre prospective study. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:55-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2012;10:40-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the therapeutic efficacy and safety of combined oral tranexamic acid and topical hydroquinone 4% treatment vs. topical hydroquinone 4% alone in melasma: A parallel-group, assessor-and analyst-blinded, randomized controlled trial with a short-term follow-up. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:235-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of oral tranexamic acid in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:1495-501.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of oral tranexamic acid as an adjuvant in Indian patients with melasma: A prospective, interventional, single-centre, triple-blind, randomized, placebo-control, parallel group study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2636-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randomised, controlled, double-blind study of combination therapy of oral tranexamic acid and topical hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:237-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranexamic acid is a weak provoking factor for thromboembolic events: A systematic review of the literature. American Society of Hematology Washington, DC 2013

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]