Translate this page into:

The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: I. Epidemiology, risk factors and clinical features

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Verma SB, Panda S, Nenoff P, Singal A, Rudramurthy SM, Uhrlass S, et al. The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: I. Epidemiology, risk factors and clinical features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:154-75.

Abstract

Dermatophytosis has attained unprecedented dimensions in recent years in India. Its clinical presentation is now multifarious, often with atypical morphology, severe forms and unusually extensive disease in all age groups. We hesitate to call it an epidemic owing to the lack of population-based prevalence surveys. In this part of the review, we discuss the epidemiology and clinical features of this contemporary problem. While the epidemiology is marked by a stark increase in the number of chronic, relapsing and recurrent cases, the clinical distribution is marked by a disproportionate rise in the number of cases with tinea corporis and cruris, cases presenting with the involvement of extensive areas, and tinea faciei.

Keywords

Fixed-dose combination creams

superficial dermatophytosis

tinea

topical steroids

Introduction

We aim to comprehensively cover various aspects of the current epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India. The disease has attained a significant magnitude and is now being observed in other distant nations as well1,2 often as an extensive and difficult to treat entity with diverse morphology. Recalcitrant superficial dermatophytosis has the potential to become a public health issue in many parts of the world if we do not make an active attempt to understand it in its entirety, take timely measures, and involve public health agencies and the World Health Organization.

This review intends to concentrate on the commonest clinical types of dermatophytoses in the current scenario and will not deal with all clinical variants (e.g., tinea unguium, tinea pedis, tinea capitis). A comprehensive English language literature search was performed across multiple search engines (PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE and Cochrane). MeSH terms (“tinea,” “ Dermatophytosis,” “epidemiology,” “clinical features,” “diagnosis of dermatophytosis,”“antifungal resistance,” “topical” and “systemic”) alone and in combination were considered. Available literature pertaining to dermatophytosis in the last 7 years (2014–2020) with particular emphasis on Indian studies was included.

The phenomenon under review is recent and treatment options are still evolving. Studies on it are lacking, and we have included many previously undescribed but now common clinical observations of the authors and a large number of dermatologists in India. There is a strong need to study this entity and its various treatment options in greater detail.

This review is divided into three parts: Part I covers epidemiology, risk factors and clinical features; Part II will discuss diagnostic methods and taxonomical aspects of the causative dermatophytes of this outbreak; Part III will deal with antifungal resistance, a very important feature of this current phenomenon, and prevailing treatment options.

Epidemiology of dermatophytosis in India

Superficial dermatophytosis affects 20-25% of the world population and is a common infective dermatoses in clinical practice.3 What was once considered an innocuous, easy-to-treat infection of tropical and subtropical countries, mainly seen during the summer and rainy seasons, has now become a perennial and difficult to treat entity in India. According to recent studies, there has been an increase in the incidence of dermatophytosis across the country in the past decade and especially so over the past 5–6 years.4,5 This increase has been at an alarming rate and has resulted in an epidemic-like situation in the country.

Incidence and prevalence

Though there have been many studies on superficial dermatophytosis, it is difficult to calculate the exact incidence and prevalence owing to a paucity of community-based surveys. The current reported prevalence in India falls in a very wide range (6.09%6– 61.5%7). A prevalence of 6.09% to 27.6% has been reported in studies from south India,6,8 while a high prevalence of 61.5% has been recorded in north India.7 Most of this data comes from hospital-based studies over periods ranging from 1- 2 years6-8 Interestingly, though dermatophytosis is expected to be more prevalent in the hot and humid climates of south India and less so in north India, no such association is apparent. We feel that there has been a rising trend of dermatophytosis all over the country in the last 5–7 years.

Further, there appears to be a steady increase in the incidence of chronic, relapsing and recurrent dermatophytosis; it is not uncommon to encounter disease durations running into months or years. Agarwal et al. in 2014 reported disease of >3 months in 163/300 patients (62.5%).9 Of the 300 patients, 28 (9.3%) had had similar episodes in the past and 87 (27.7%) patients had been treated previously with medications other than antifungal drugs. Since then, there has been a rising trend of recurrent and relapsing dermatophytosis [Table 1].9-16

| Author and year | Number of patients(n) | Place of study | Relapse/recurrent SD(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agarwal etal., 20149 | 300 | Jaipur(North India) | Disease duration >3 months- 62.5%Relapse-9.3% |

| Sharma etal., 201710 | 192 | Sikkim(East India) | Relapse-60.4%Recurrent-34.3% |

| Mahajan etal., 201711 | 265 | Varanasi(North India) | Disease duration of 2years- 35.8% |

| Pathania etal., 201812 | 150 | Chandigarh(North India) | Recurrent- 9.3%(multiple recurrences, (3–10) usually within a few days to 4weeks of stopping treatment) |

| Vineetha etal., 201813 | 120 | Kottayam(South India) | Chronic-68% |

| Tigga etal., 201814 | 300 | NewDelhi(North India) | Reinfection-49%Recalcitrant-44.3% |

| Rudramurthy etal., 201815 | 195 | Chandigarh(North India) | Recurrent-60% |

| Singh etal., 201916 | 150 | Varanasi(North India) | Chronic-65.3%Relapsing-34.6% |

These trends are unique to the present epidemic-like situation of dermatophytosis in India and are not described in the standard dermatology textbooks from the Western world.

Age and sex

In general, dermatophytosis occurs most frequently in postpubertal hosts, with the exception of tinea capitis. Conventionally, men are more frequently affected than women because of the significantly high incidence of tinea cruris, tinea pedis and tinea unguium in men,17 and outdoor work predisposes men to hot, humid and sweaty conditions conducive to the growth of dermatophytes. However, in the present epidemic, these boundaries are getting blurred with the rising incidence of dermatophytosis in women and children [Table 2].7,12-15,18-25 It is clear that the male:female ratio is < 2 in all the studies published in the last 3–4 years12-14,18-20 in contrast to earlier studies where the ratio was 3–5, indicating a rising prevalence in women.24,25 Recent studies have even shown the reversal of the men:women ratio.13,19 As most Indian studies on superficial dermatophytosis have included only adult patients, the exact incidence of cases among children cannot be ascertained. Only a single study by Noronha et al. from south India has included patients of all age groups.26 This study reported that 21.3% of patients were in the age range of 0–10 years, similar to the proportions of adolescents and adults (21.3% and 22.7% in the age range of 11–20 years and 21–30 years, respectively).26 In our experience, it is not uncommon to see infants, toddlers and children of all age groups presenting with all morphological types of dermatophytosis, viz., extensive tinea cruris, tinea corporis and tinea faciei.

| Author and year | Totalpatients(alladults) | Men: women | Age range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazarika etal., 201918 | 130 | 1.5:1(60%:40%) | 21–30years(32%) 31–40years(23%) |

| Patro etal., 201919 | 294 | 0.88:1(47%:53%) | 18–40years(86.7%) f/b 41–60years(13.2%) |

| Vineetha etal., 201813 | 120 | 1:1.1 | 1stepisode- 10–20years Chronic- fourth to fifth decade |

| Tigga etal., 201814 | 300 | 1.97:1 | 15–30years(66.3%) |

| Pathania etal., 201812 | 150 | 1.7:1(63%:37%) | Mean age- 32.5years |

| Rudramurthy etal., 201814 | 195 Children-7(3.6%) Neonates-4(2%) |

2.8:1(73.8%–26.1%) | Median age- 33.5years |

| Dabas etal., 201720 | 124 | 1.7:1(64%–36%) | Mean age- 31.2years |

| Ramaraj etal., 201621 | 210 | 4:3(57.1%:42.8%) | 21-40years(49%) f/b 41-60years(29%) |

| Poluri etal., 201522 | 110 | 2:1(67.2%–32.7%) | 21–40(64.5%) |

| Kaur etal., 20157 | 351 | 2:1(67.2%:32.7%) | 21–30years(23.3%) f/b 31–40years(20.5%) |

| Maulingkar etal., 201423 | 321 | 2.4:1 | 21–30years(26.5%) 31–40years(35.5%) Low prevalence- <10 and>50years |

| Bhatia and Sharma, 201424 | 202 | 5.7:1 | 21–50years(64.9%) |

| Bhagra etal., 201425 | 100 | 4:1 | Third decade(28%) |

Chronic dermatophytosis (disease for more than 6 months with or without recurrence despite being treated) is more common in the late middle age group, around fifth decade, which is attributed to waning immunity, comorbidities like diabetes and other risk factors such as positive family history, use of topical steroid-antifungal creams, immunosuppressants intake etc.14 However, in a recent study on 150 patients of recurrent dermatophytosis, the mean age of patients withchronic dermatophytosis was lower (32.5 years).12

Familial cases

Recent studies have reported a very high frequency of history of dermatophytosis in close contacts (72-82%)11,12,19 Chronicity and recurrent infection have probably contributed to the rise in the incidence of familial infection. Connubial dermatophytosis is common.5 The spouse and children, often the whole family, have concomitant dermatophytosis. A high prevalence occurs in people living in overcrowded homes, slums, hostel rooms and dormitories. A careful inquiry into family history has become the norm; all affected family members must be treated simultaneously to prevent recurrences.

Urban versus rural areas and literacy

People from both urban and rural areas are at increased risk of dermatophytic infections.Studies from the first half of the past decade reported a rural predominance, possibly due to the high frequency of outdoor work including agriculture predisposing to increased perspiration.6,27 However, studies in the last 5 years have shown greater proportions of patients from urban areas (around 80% of patients).7,22 This change was initially attributed to increased awareness, literacy and cosmetic concerns in the urban population leading them to seek medical attention. However, the predominance seems to be dependent on the place and nature of the study. The relatively easy availability of creams containing irrational combinations of potent topical steroids along with antifungal and antibacterial agents in urban areas as compared to rural might be a contributing factor.

Education and literacy have not been commented upon much in reports concerning the increased incidence of dermatophytosis. Kaur et al.7 reported the frequency of literate patients (64.6%) to be more than the illiterates (35.3%). Similarly, a recent study showed that the majority of their patients had medium educational qualifications (60.20%).19 These findings can also perhaps be interpreted as above.

Socioeconomic status

A higher proportion of patients with dermatophyte infections are still from lower socioeconomic groups, with studies reporting an incidence of 61–67%.6,22,26 This is followed by lower-middle and medium socioeconomic strata.9.19,26 Poor standards of living, lack of hygiene, overcrowding and poor nutrition in the lower socioeconomic groups promote the growth of dermatophytes, increasing the risks of infection, chronicity and recurrence.

Occupation

People engaged in outdoor activities in hot and humid environments are at a greater risk of infection since this provides a favorable environment for dermatophytes. Recent studies too have reported that manual laborers are most commonly affected.13,18.22 Farmers are at an additional risk due to increased exposure to fungal pathogens from the environment and frequent contact with soil and animals.9

More homemakers with active infection are seen now.13 The hot environment of the kitchen with increased sweating favors the growth of dermatophytes, making homemakers susceptible. Rudramurthy et al. found homemakers as the most common affected group (25.1%) in their study.15

An increased frequency of dermatophytosis has also been reported in students recently.9,10,22 Increased sweating during school and sport activities along with wearing of school uniform and footwear for prolonged hours might be contributory factors. Moreover, wearing tight-fitting synthetic clothing, common amongst younger individuals, provides damp and warm skin conditions5,13 possibly contributing to the increased prevalence, recurrence and chronicity of these infections in them.

Topical steroid abuse

Topical steroid misuse may be the most important cause of the current outbreak of chronic and recalcitrant dermatophytosis. A strong temporal association has been observed between the increasing availability and irrational use of the combination creams (antifungal-steroid or antifungal-antibiotic) with the sudden increase in chronic, recurrent and refractory cases in the past 4–5 years.5 Potent steroid-containing creams are easily available over the counter without prescription. They are often suggested by pharmacists or friends, or are prescribed by general practitioners, and patients keep using them erratically for months to years. At the time of presentation to the dermatologist, most patients are found to have taken some form of treatment [Table 3]. Oral/topical azoles and topical steroids alone or in combinations are commonly self-administered by patients with dermatophytosis.11 Studies in the last 1-2 years reveal that the frequency of prior application of topical steroid-containing combination creams is very high (42%16–81%4) among patients. Ironically, the use of topical antifungals was lower, seen in 5.7%9–47%13 of patients [Table 3].

| Author, year | Topical steroids alone or combination | Topicalantifungalalone |

|---|---|---|

| Nenoff etal., 20194 | 82(81.3%) | 95(93.1%)(topical and oral antifungals |

| Singh etal., 201916 | 63(42.0%) | 31(20.7) |

| Vineetha etal., 201813 | 63% | 47%(azoles- 28%, allylamines in 19%) |

| Pathania etal., 201812 | 80(53.3%) | |

| Mahajan etal., 201711 | 187(70.6%) | 15(5.7%) |

Causative organism

Trichophyton mentagrophytes (mostly Trichophyton interdigitale) used to be the predominant organism responsible for superficial dermatophytosisbefore 1935 worldwide.28,29 Thereafter, an epidemiological shift began with Trichophyton rubrum replacing Trichophyton. mentagrophytes and emerging as the predominant organism by 1954 in many countries and continents (United States, Australia, Germany, Switzerland and Netherlands) including India with a reported incidence of up to 80%.29 The environmental factors (humidity, temperature, trauma), internal factors (host-parasite relationship, host susceptibility) and immunological factors have been speculated for this shift along with the changing virulence of the organism.4,29 It remained the most prevalent causative agent till the recent upsurge of dermatophytosis, when Trichophyton mentagrophytes has again emerged as the predominant organism. The same factors have been thought to be responsible as during the previous epidemiological shift.4 Moreover, a probability that the zoophilic Trichophyton mentagrophytes has acclimatised itself and has undergone anthropization leading to easy transmission among humans has been suggested.4 In the past decade, and especially from the beginning of 2012, the reported prevalence of Trichophyton mentagrophytes has not only increased,6,7,10,12,18,22,26,30 but it has even replaced Trichophyton rubrum in a few studies[Table 4].9-11,24,26 The most recent studies have found Trichophyton mentagrophytes in more than 90% of their dermatophyte isolates. In a recent large multicentric study, Trichophyton mentagrophytes/ Trichophyton interdigitale complex was identified in 93.2 % and Trichophyton rubrum in only 6.8%.4 Yet another study recently demonstrated 97.2% of isolated dermatophytes to be Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex with the most significant species being Trichophyton interdigitale.14 Singh et al. too identified Trichophyton interdigitale in 94% of cases.16

| Author, year | Place | Predominant species(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nenoff etal., 20194 | Multicentric | T. mentagrophytes(93.21) |

| Vineetha etal., 201813 | Kottayam(Kerala) | T. rubrum(21) |

| Tigga etal., 201814 | NewDelhi | T. mentagrophytes (97.2) |

| Pathania etal., 201812 | Chandigarh | T. mentagrophytes (40) |

| Rudramurthy etal., 201815 | Chandigarh | T. interdigitale (66.1) |

| Mahajan etal., 201711 | Varanasi | T. mentagrophytes (75.9) |

| Sharma etal., 201710 | Sikkim | T. mentagrophytes (40) |

| Dabas etal., 201720 | NewDelhi | T. interdigitale (56) |

| Noronha etal., 201626 | Mangalore | T. mentagrophytes (48.3) |

| Ramaraj etal., 201621 | Chennai | T. rubrum(48.95) |

| Poluri etal., 201522 | AndhraPradesh | T. rubrum(58.06) |

| Kaur etal., 20157 | NewDelhi | T. rubrum |

| Lakshmanan etal., 20158 | Tamil Nadu | T. rubrum(79) |

| Surendran etal., 201430 | Mangalore | T. rubrum(67.5) |

| Maulingkar etal., 201423 | Goa | T. rubrum(38.2) |

| Bhatia and Sharma, 201424 | Himachal Pradesh | T. mentagrophyte(63.5) |

| Bhagra etal., 201425 | Shimla | T. rubrum (66.17) |

| Agarwal etal., 20149 | Jaipur | T. mentagrophytes(37.9) |

| Vyas etal., 201327 | Jaipur | T. violaceum(43.3) |

T. violaceum (43.3) T. rubrum: Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes: Trichophyton mentagrophytes, T. violaceum: Trichophyton violaceum, T. interdigitale: Trichophyton interdigitale

Trichophyton mentagrophytes exhibits a rapid growth in primary culture within 5–7 days; this might explain the extensive involvement, inflammatory lesions and fomite transmission frequently seen now.5

Immunopathogenesis of Chronic Dermatophytosis

Fungal cells evade host immune responses to survive. Mechanisms include masking of cell wall-associated carbohydrates, shielding of stimulatory surface recognition molecules, prevention of toll-like receptor recognition, shedding of decoy components and downregulation of the complement cascade.31-33

A recent study from India demonstrated a higher expression of Th17 and Treg cell markers on CD4+ cells of patients with chronic dermatophytosis as compared to controls.34 It was speculated that the interaction between the cell wall antigen mannan with the host cell receptor triggers a cascade of dysregulated cytokines eliciting Th17 mediated inflammation but also leads to the unhindered activation of Treg cells undergoing a phenotype change to an alternate lineage. Hence, despite antifungals, the high fungal burden becomes detrimental to a beneficial effector T-cell response. This perpetuates the imbalance with an altered Th17/Treg ratio preventing fungal clearance.

Clinical Features of Superficial Dermatophytosis

The clinical changes in the appearance of dermatophytic infections observed in India have been summarized in Box 1.

| Changes in the distribution of lesions in dermatophytosis |

|---|

| Tinea corporis et cruris - the most common presentation |

| Tinea facei - much more common than earlier |

| Multiple lesionsseen, multiple body sites involved |

| No concomitant increase in tinea unguium, tinea pedis or tinea capitis reported |

| Erythrodermic variants seen – not infrequently |

| Changes in the clinical behavior of dermatophytosis |

| Rapid spread of lesions to form large, bizarre- shaped patches |

| Early involvement of distant areas compared to the past |

| Varying degrees of inflammation |

| Easy spread to other family members often causing the entire family to suffer. |

| Post tinea eczema/dryness leading to persistence of itch |

| Flare of lesions with increased inflammation within the lesions of tinea after starting oral potent antifungal, with occasional systematization |

| Concomitant bacterial infections like furunculosis have become common |

| Chronic dermatophytosis, recurrences, relapses common |

| Changes in morphology |

| Steroid-modified tinea |

| Varying morphology – arcuate, dumb-bell shaped, bizarre geographic lesions |

| Double-edged tinea |

| Tinea pseudoimbricata |

| Tinea incognita – ill-defined borders, unclear borders – difficult to recognize tinea |

| Eczematous lesions |

| Tinea mimicking other dermatoses |

| Involvement of unusual locations |

| Genital dermatophytosis of males and females |

| Superficial dermatophytosis of scalp skin |

| Tinea auricularis |

| Tinea labialis |

| Tinea blepharitis and ciliaris |

| Tinea of vellus hair |

| Tinea over immunocompromised districts /sites affected by tinea being recognized as immunocompromised districts |

| Signs of topical/oral/injectable steroid abuse and irritant applications |

| Characteristics of itch in dermatophytosis |

| Often disabling itch ,frequent nocturnal aggravation |

| Persistent itch after the resolution of lesions |

| Changes in the impact of disease on society |

| Distressing to the patient and family; high impact on quality of life |

| Major financial burden |

| Confusing profusion in the manufacture of available topical and oral antifungals agents by pharmaceutical companies |

Changes in clinical behavior

Quick evolution

Sudden appearance and quick evolution of lesions, sometimes within days, seems to be common, unlike in the past.

Induction of varying degrees of inflammation

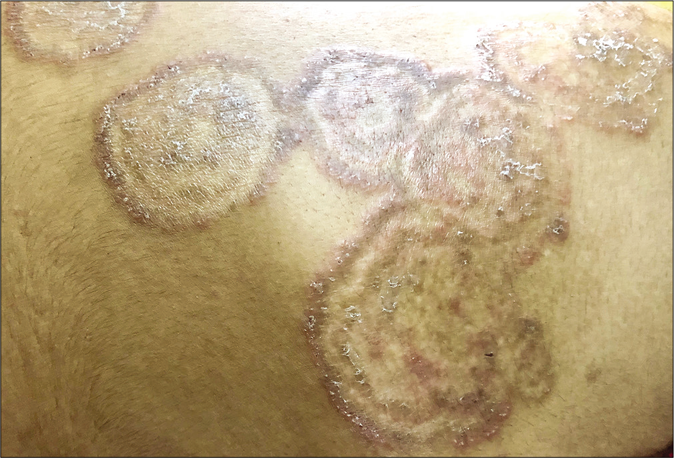

It is common now to find moderate or severely itchy, peripherally spreading, flat, whitish or brownish lesions without erythema which yield profuse powdery scales when scraped [Figure 1a]. Such lesions have been called‘non-inflammatory’ superficial dermatophytosis35, but the term may be inaccurate as the absence of erythema does not necessarily mean the absence of inflammation.

- Annular plaques of tinea corporis with minimal inflammation

Multiple lesions in different anatomical locations exhibiting varying degrees of inflammation are also seen [Figure 1b]. Many patients report noticing diurnal changes, with lesions tending to get more erythematous and raised and the edges becoming more defined at times [Figure 1c]. Heat, humidity, sweating, tight clothing, friction, exercise and topical corticosteroid-containing fixed-dose combinations, are known to modify the appearance of lesions. These observations necessitate further research on host immunity, the virulence of the organism and the nuances of topical steroid use.

- Multiple annular erythematous plaques of tinea with peripheral pustular borders suggestive of severe inflammation

- Tinea corporis et cruris showing varying degrees of inflammation in the same patient

Exacerbation of inflammation after starting treatment

An abrupt increase in the number of lesions with increased erythema, edema and occasionally pustulation, is seen on starting oral antifungal drugs like itraconazole in some cases [Figure 2a and b]; many of them have been abusing topical steroid-containing fixed-dose combinations. This phenomenon could be on account of withdrawal of corticosteroid with the administration of oral antifungal agents causing a recovery of the local cell-mediated immunity. Another phenomenon is the abrupt onset of multiple papules, plaques and at times, disseminated eczematous lesions with itching and burning in areas other than those with pre-existing tinea. These lesions appear soon after starting oral antifungal therapy and can cause diagnostic confusion between a dermatophytid and an adverse reaction to the antifungal agent, usually itraconazole.

- Sudden exacerbation of tinea with the appearance of multiple eczematous scaly lesions after starting antifungal therapy

- Sudden appearance of erythema and edema overlying a plaque of tinea faciei after starting antifungal therapy

Chronicity, recurrence and relapse

Chronic dermatophytosis may be defined as disease lasting for more than6 months in a patient who has been adequately treated. It is common for patients with such longstanding infection to have received treatment comprising fixed-dose combinations as also suboptimal doses and durations of oral and topical antifungal drugs. Recurrent dermatophytosis has been defined as disease in which there is a recurrence of lesions within 6 weeks after completion of treatment.36 Relapse refers to lesions occurring more than 6–8 weeks after a patient has been cured clinically. All these presentations have become very common in current practice.37

Changes in the morphology of lesions

Well-defined, centrifugally spreading lesions with central clearing and an advancing border, as described in textbooks, are not the rule now. A plausible explanation for this is that treatment-naïve cases are now uncommon.

The following are the morphological forms encountered in the current scenario:

Steroid-modified tinea

Lesions were labeled tinea incognita/tinea incognito in the past because their appearance was different from that of a “classic” lesion of tinea38 due to the application of steroid creams. Though a majority of patients now present with altered lesional morphology after having used fixed-dose combination creams with steroids (most often clobetasol propionate or betamethasone dipropionate), most such lesions are not “incognito” in a strict sense.39 It is usually possible in such cases to discern an active border with or without scaling, as typical in superficial dermatophytosis. Therefore, “steroid-modified tinea” is a more accurate term.39 True cases of tinea incognita are fortunately uncommon.

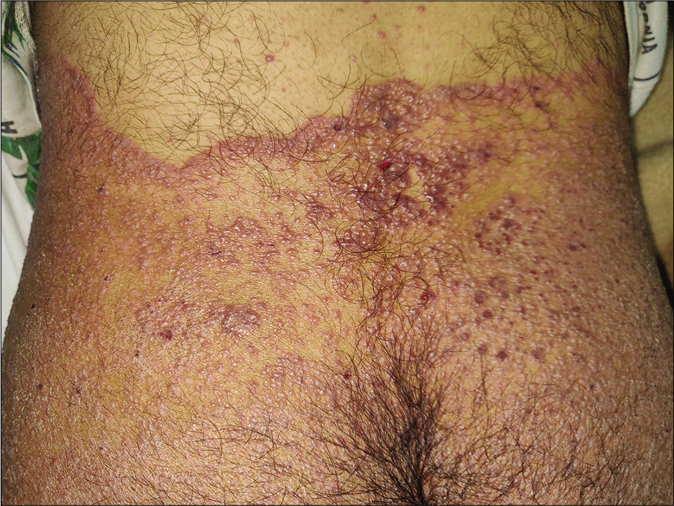

Varying morphology

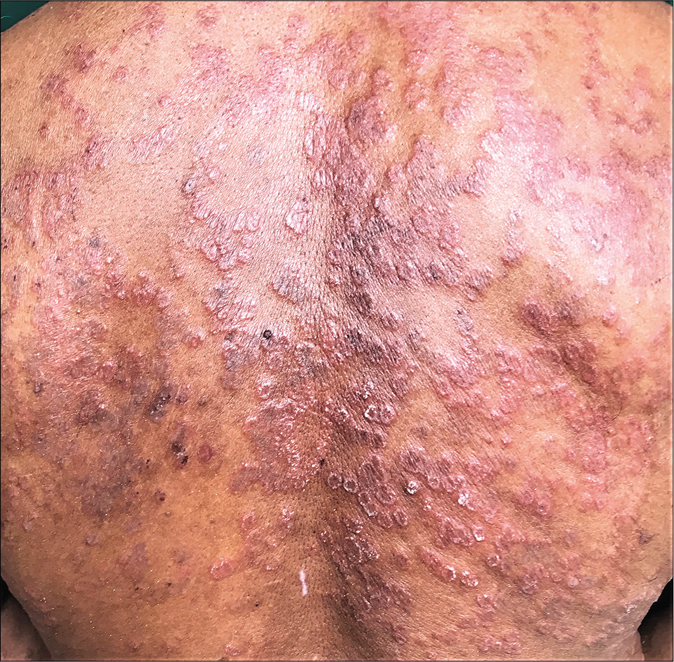

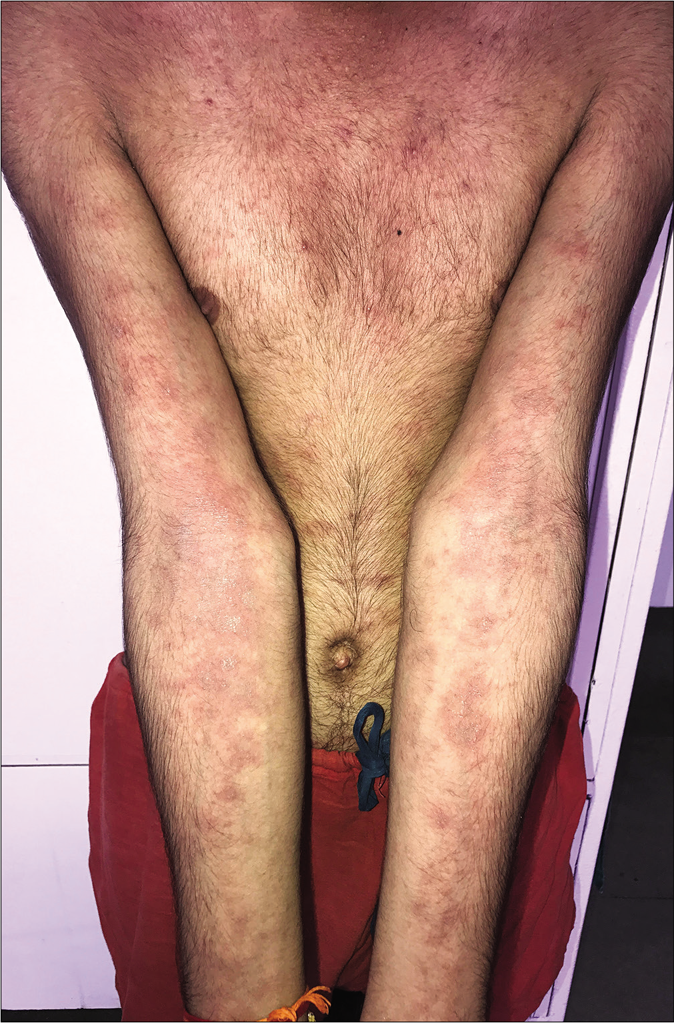

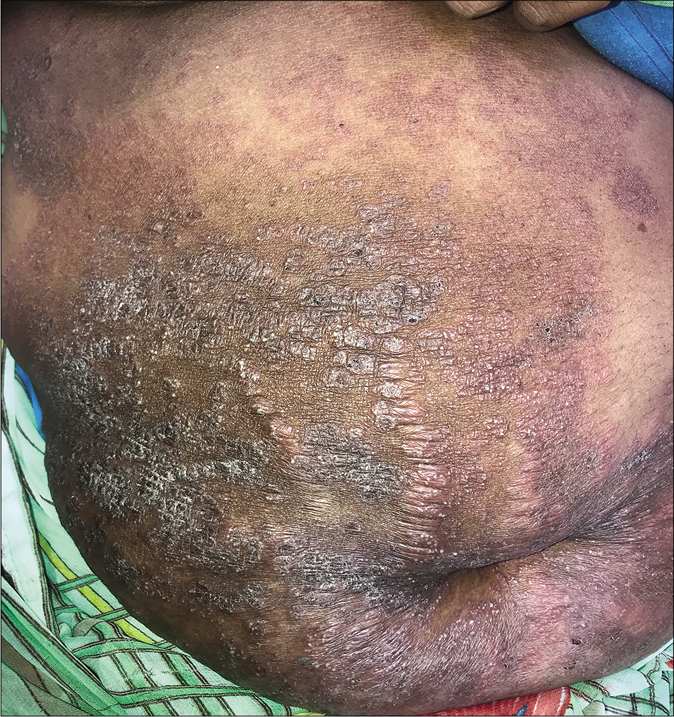

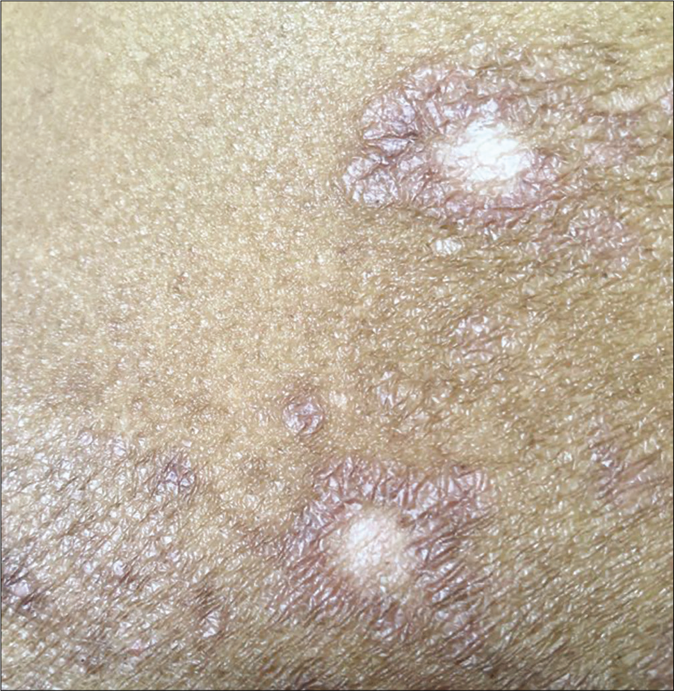

Unusually large lesions are seen, either due to centrifugal spread or by coalescence of multiple lesions. Circular or annular lesions, [Figure 3], arcuate and dumbbell-shaped lesions where two annular or circular lesions coalesce, annular lesions with pustular borders [Figure 4], and bizarre geographic lesions are common. Erythrodermic presentations of dermatophytosis are seen in immunosuppressed as well as immunocompetent individuals [Figure 5a and b].40

- Multiple annular lesions coalescing to form a plaque

- Multiple annular lesions coalescing to form a plaque

- Multiple coalescing lesions with pustules

- Erythrodermic variant of superficial dermatophytosis

- Erythrodermic variant of superficial dermatophytosis

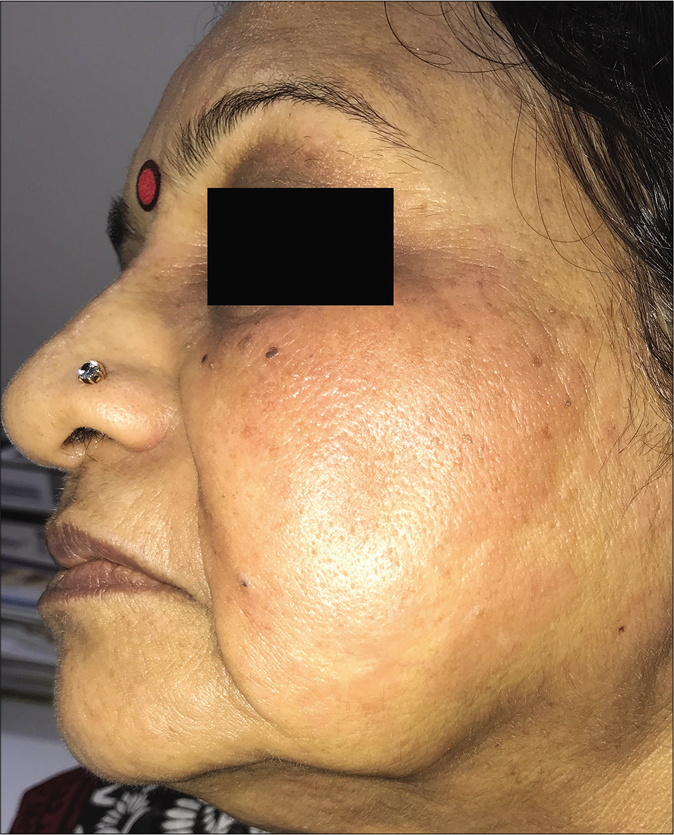

Incomplete central clearance and eczematous appearance

It is common to see incomplete clearing in the centre of lesions leading to variably defined areas of erythema with or without scaling i.e.,“eczematous tinea” [Figure 6a and b]. The natural course of the disease is for cell-mediated immunity to mount an inflammatory response and increase the epidermal cell turnover to eliminate the fungus by shedding the stratum corneum41. Lesions treated with steroids show activity in the centre as well as in the peripherally spreading margins.5 Topical steroid abuse slows down cell turnover and downregulates beneficial proinflammatory mediators, aiding survival of the fungus.

- Eczematous variant of tinea facei

- Eczematous variant of tinea corporis

“Double-edged tinea” and tinea pseudoimbricata

Erratic application of fixed-dose combinations and steroid creams in tinea switches inflammation on and off, leading to “double-edged” tinea [Figure 7 ].42 The degree of inflammation in such cases often is high, and residual post-inflammatory hyperpigmented “double edges” persist for a long time after successful treatment too [Figure 7]. At times, the double edges are well-defined, running parallel to each other and with central crusting and erosions, resulting in a pseudoporokeratotic appearance [Figure 8a and b]. Repeated on-and-off cycles of inflammation for long periods can lead to concentric rings of tinea described as “tinea pseudoimbricata”[Figure 9a and b]. A “rings within a ring” appearance is also not uncommon and is characterized by smaller scaly lesions of tinea within a centrifugally spreading larger annular lesion, often with more than one border.43 Double-edged tinea, tinea pseudoimbricata and tinea “rings within rings” lesions are all highly suggestive of steroid abuse, especially erratic use of steroid-containing fixed-dose combinations.44

- Double-edged tinea cruris

- Steroid modified tinea corporis with pseudoporokeratotic edges

- Steroid modified tinea with pseudoporokeratotic edges

- Tinea pesudoimbricata

- Tinea pseudoimbricata

Another uncommon entity is tinea recidivans that describes the appearance of lesions at the periphery of a healed lesion [Figure 10a and b].

- Tinea recidivans

- Tinea recidivans on upper torso

Pustular lesions in tinea

Pustular lesions are often seen at the periphery of inflammatory erythematous lesions of tinea being treated with potent topical steroids. In some cases, each ring of a tinea pseudoimbricata lesion can be studded with pustules, giving rise to a cockade pattern [Figure 11].

- Cockade pattern of pustular lesions in steroid-modified tinea

Majocchi’s granuloma

Rarely, dermatophytes may invade the dermis owing to the reduced local immunity induced by abuse of topical steroids. Such cases show pruritic papules, pustules and nodules in the areas of preexisting dermatophytic infection [Figure 12], and granulomatous perifollicular inflammation on histology.

- Majocchi’s granuloma (Picture Courtesy – Dr. Chetan Rajput)

Bullous tinea

Intense inflammation caused by the zoophilic Trichophyton mentagrophytes and a heightened delayed type of hypersensitivity reaction are thought to be causes of a vesicular or bullous presentation. This is characterized by annular lesions with raised, vesicular edges.45

Superficial dermatophytosis mimicking other dermatological conditions

Tinea has been observed to mimic a wide variety of conditions including lupus erythematosus,46 psoriasis, lichenoid lesions, atopic eczema,47 nummular eczema, erythema multiforme,48 granuloma annulare, granuloma faciale, lymphocytic infiltration of the skin, pityriasis rosea, seborrheic dermatitis,49 leprosy,50 molluscum contagiosum,51 rosacea52 and annular secondary syphilis,37 pustular psoriasis, Sweet’s syndrome and impetiginized herpes.53 Cutaneous dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes mimicking bullous pemphigoid clinically, histopathologically and on direct immunofluorescencehas been recently reported.54 Though many of these are isolated cases described in the Western literature, it is now perhaps prudent tokeep in mind the possibility of dermatophytosis when encountering such presentations in our patients.

Change in sites of skin involvement

The involvement of multiple body sites is common. Tinea corporis et cruris is the most common presentation;3 individual tinea corporis and tinea cruris are the next two commonest. Lesions at sites of occlusion like the waist and inframammary areas are frequent in female patients [Figure 13a,b].

- Tinea corporis limited to the area of occlusion by wrist band

- Tinea corporis presenting as a large annular plaque limited to the area of waistline along the line of occlusion by drawstring

An interesting observation is the absence of a proportionate increase in tinea unguium, tinea pedis and tinea capitis.5

Involvement of unusual locations

Genital dermatophytosis

Genital dermatophytosis is not usually mentioned separately in standard textbooks, probably because of its rarity. Together with tinea cruris, it is referred to as tinea pubogenitalis. There is a male predominance with concomitant tinea cruris or tinea cruris et corporis, and the vast majority of these patients have a history of applying fixed-dose combinations containing topical steroids.55 The base of the penis is most often affected, followed by the shaft and rarely, the outer prepuce. The scrotum is affected less commonly. Lesions on the penile shaft vary from well- to ill-defined areas of scaling [Figure 14] to annular lesions with or without pustules, on the dorsal [Figure 15], lateral or ventral aspects. Many cases are detected during the examination because they are asymptomatic and patients have sometimes not even noticed them. These lesions usually resolve within days of application of topical antifungal agents. We would like to stress the importance of identifying and treating them because otherwise they may easily become afocus for recurrence.

- Tinea cruris with male genital dermatophytosis manifesting as ill-defined scaly plaques

- Tinea cruris with male genital dermatophytosis manifesting as well-defined annular plaques

A similar entity has been noticed in women with involvement of only the pubic region, or as a part of a larger plaque of tinea cruris [Figure 16].56 Waxing or shaving the area may allow the dermatophyte deeper and cause extension of the infection. Patients must therefore be instructed that trimming the hair with scissors is preferable instead.

- Tinea cruris with female genital dermatophytosis presenting as a double-edged annular plaque involving the pubic area

Superficial dermatophytosis of the scalp skin

Tinea of the glabrous scalp is a distinct entity in the current scenario in adults as well as children, where lesions involve the skin of the scalp, most often due to secondary spread, without apparent clinical, dermatoscopic or mycological involvement of the hair [Figure 17a], this last feature differentiating it from tinea capitis. Tinea corporis may extend from the nape of the neck to the lower occipital scalp, and tinea faciei to the lateral and anterior aspects of the scalp. The involvement usually does not extend beyond a centimeter or so into the scalp though occasionally, potassium hydroxide-positive, scaly, well-circumscribed areas may be seen more centrally.56 This picture defies the earlier notion that sebum is fungistatic and prevents the proliferation of fungus; the higher virulence of Trichophyton mentagrophytes may be one explanation.

- Dermatophytosis of the scalp skin manifesting as an erythematous scaly, ill-defined plaque on the occipital area

Lesions are better delineated with the hairs on the area trimmed. Dermoscopy [Figure 17b] and potassium hydroxide examination of the scalp skin scrapings help to differentiate this presentation from psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp. More studies are needed to explore whether there is subclinical involvement of hair in this condition.

- Dermatoscopy of scalp skin dermatophytosis– manifesting as fine scaling. Dermlite DL4N, polarized mode x10

Tinea faciei

An increasing frequency of tinea faciei has been noted in adults as well as children.3 While it is often secondary to tinea elsewhere on the body, it can also be the first to occur, followed by disease elsewhere. The face may be the only site involved and remain so in some patients.

Lesions vary from a well-defined, annular, scaly plaque or multiple scaly plaques studding parts of the face to at times, diffuse erythema and scaling with barely discernible edges. The latter are examples of true ‘tinea incognita’ as they are difficult to diagnose and a potassium hydroxide examination is necessary. Tinea faciei often shows photoexacerbation with patients complaining of increased erythema, itching and transient edema of the affected areas when exposed to sunlight.

The following entities need special mention here:

Tinea facei involving the external ear and “tinea auricularis”: Tinea faciei often shows extension to the skin of the ear. Lesions often extend to the lateral scalp and beyond when the ear is involved [Figure 18]. Involvement of one ear with a scaly, erythematous, papulosquamous eruption on the same side of the face points strongly towards the diagnosis of tinea faciei. External ear involvement in children with tinea capitis has been referred to in the past as the “ear sign”.57 We propose that this “ear sign” be extended to the context of tinea faciei as well, especially in the current scenario where tinea faciei has become so common.

Very rarely, involvement of only the ear may occur, which can be difficult to recognise with no clinical clue of dermatophytosis elsewhere on the face or the body. We propose the name “tinea auricularis” for this presentation [Figure 19a and b].56

Tinea facei extending onto the lips and tinea labialis: Lip involvement can occur due to contiguous spread from tinea faciei [Figure 20 a-c] or as an isolated phenomenon, tinea labialis. It is rare and presents as a well-circumscribed scaly lesion or as diffuse scaling over the entire lip.56

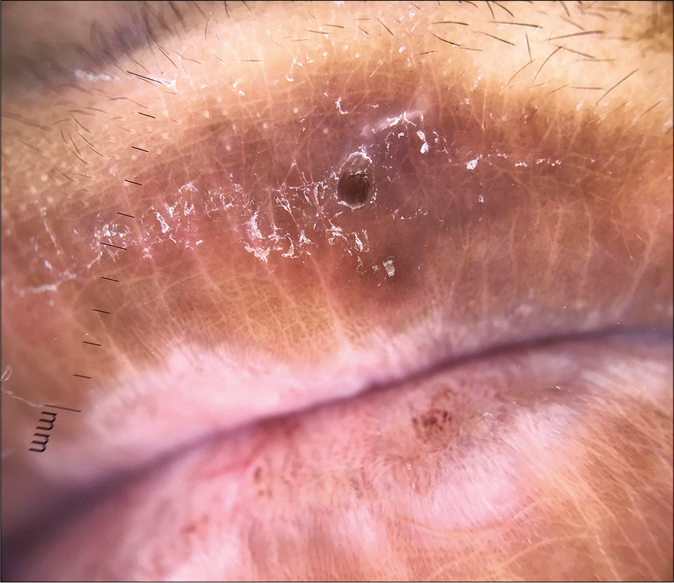

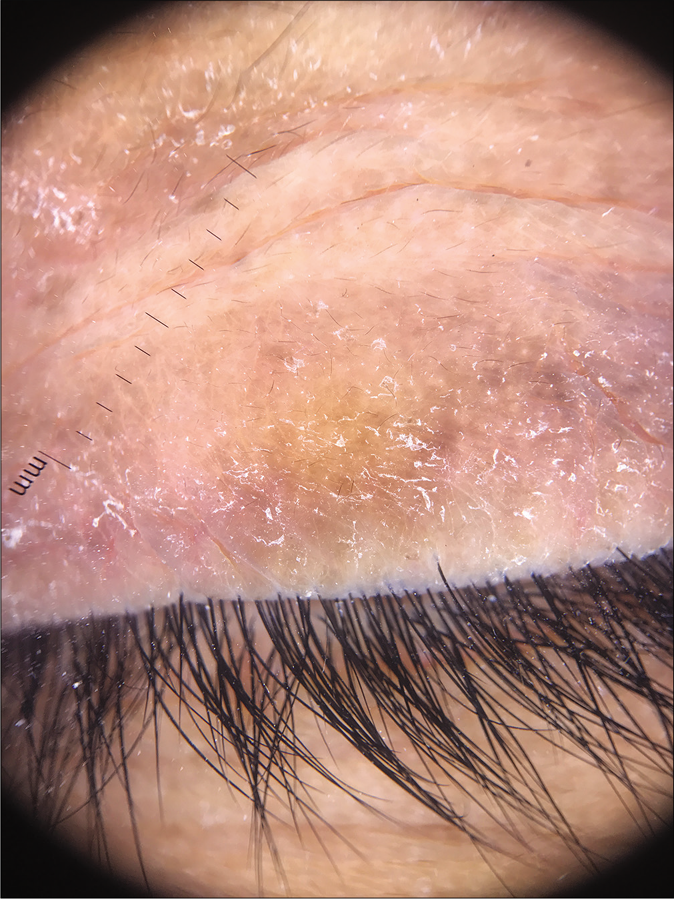

Tinea blepharitis with tinea ciliaris: The term tinea capitis by definition, includes dermatophyte infections of the scalp, eyebrows and eyelids.58 Rarely, dermatophytosis can localize itself to the eyelids59 [Figure 21a and b], eyelashes or periocular area [Figure 22] without any involvement of the scalp.56 With signs of rubbing and scratching, it can then easily be misdiagnosed as atopic blepharitis/ allergic contact dermatitis or atopic involvement of the periocular area, and treated with topical steroids. The topical steroid perpetuates the infection which can later involve the skin of the face.

- Tinea faciei with extension to the ear

- Tinea auricularis

- Tinea auricularis

- Tinea faciei presenting as an annular plaque with extension to the upper lip

- A close-up view of tinea faciei presenting as an annular plaque with extension to the upper lip

- Dermatoscopy of involvement of lip by superficial dermatophytosis showing scaling at the active border with crusting. DermLite DL4N, polarised mode, ×10

- Superficial dermatophytosis of the upper eyelid with involvement of the eyelid margin

- Dermoscopy of superficial dermatophytosis involving the eyelid margin presenting with fine scaling along the eyelid margin sparing the hair shafts

- Tinea faciei involving the upper and the lower eyelids as well as the periocular area by extension

Tinea of vellus hair and subclinical infection of the nails

Subclinical infection of the nail60 or tinea of vellus hair are thought to be reasons for persistence of the fungus leading to recurrence and relapse.61 This needs to be validated with large scale studies. While tinea of vellus hair can be documented using a dermatoscope56,62 and a potassium hydroxide mount, subclinical infection of the nail can be documented by periodic acid–Schiff stain of nail clippings.

Tinea and immunocompromised districts

Animmunocompromised district is alocalised aberration in the immune control of the skin that has been damaged due to various causes63. Many of us are observing superficial dermatophytosis secondarily appearing over amputation sites, surgical incisions and tattoo sites, which are described as immunocompromised districts.64

Some dermatologists have also started documenting sites of healed tinea being immunocompromised districts. This could be explained by regional immune dysregulation at sites of tinea, and also related to topical steroid applications. One of us has documented varicella and herpes zoster appearing over partially as well as completely healed sites of dermatophytosis65 [Figure 23a]. Vitiligo has been known to develop at the sites of tinea corporis [Figure 23b] and so has lichen planus.66.

- Vesicles in a case of varicella predominantly localized to the site of tinea corporis that serves as an immunocompromised district (Photo courtesy - Dr. Sanjeev Gupta)

- Vitiligo presenting primarily at the site of active tinea corporis

Signs of topical/injectable corticosteroid use and irritant applications

Patients show much individual variation in the time taken to develop cutaneous adverse reactions, irrespective of the potency of the steroid molecule. It is also common to see patients seeking treatment of multiple stigmata of potent topical steroid abuse, like striae and hypopigmentation.

One of the commonest side effects of topical steroids is striae. They mostly occur early following the application of fixed-dose combinations containing clobetasol propionate and are most pronounced in the flexures and where the skin is thin, like the inner thighs. They are often initially erythematous (striae rubra) and eventually turn whitish (striae alba). Some striae may ulcerate making them prone to secondary bacterial infection [Figure 24].67 Some gradually worsen and ulcerate because patients continue to apply the same creams that caused them. Some striae assume a pseudoedematous appearance [Figure 25].68 Others may continue to grow despite the patient having stopped applying fixed-dose combinations. This is indicative of high potency topical steroids having adepot effect.69

- Steroid abuse in dermatophytosis leading to hypopigmentation, striae, atrophy, telangiectasia and ulceration

- Pseudoedematous appearance of striae

Striae may even occur in distal areas, where the fixed-dose combinations have not been applied. A clinical picture akin to red scrotum syndrome is also seen in some patients applying fixed-dose combinations containing topical steroids for tinea cruris, due to passive transfer of the creams.

Another common side effect of fixed-dose combinations with topical steroids is lesional and perilesional hypopigmentation; this can be seen within 3–4 weeks and is likely to be accompanied by atrophy and telangiectasia later on. Hypopigmentation and depigmentation can also be seen in patients treated with intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide [Figure 26a and b] by unqualified practitioners. These lesions are often linear or follow the course of lymphatics.

- Depigmentation at the site of intralesional steroid injection

- Close-up of depigmentation at the site of intralesional injection

Concomitant bacterial infections such as recurrent furunculosis and abscesses can complicate thedermatophyte-infected sites, due to local immunosuppression induced by topical steroids [Figure 27].

- Superficial dermatophytosis with superadded bacterial infection

Many patients present with signs of irritant dermatitis over and around the infected sites induced by home remedies made of crushed plants, flowers, balm, battery fluid, or over-the-counter preparations containing salicylic acid, sulfur, or anthralin with salicylic acid. The last combination is particularly irritant, especially in the flexures, leading to erythema, brownish discoloration, scaling and exfoliation, along with burning, pain and tenderness [Figure 28a and b].

- Irritant contact dermatitis presenting as erythema, edema and brownish pigmentation over the areas of superficial dermatophytosis due to the application of a dithranol-containing cream

- Irritant dermatitis presenting as erythema, edema, erosions and brownish pigmentation over the areas of superficial dermatophytosis due to application of dithranol-containing cream

Iatrogenic cushingoid syndrome in patients of tinea

Dermatologists are seeing an increasing number of patients, including children, presenting with longstanding lesions of tinea in multiple locations that usually wax and wane. These patients give a prolonged history of applying fixed-dose combination creams containing clobetasol propionate or beclomethasone propionate, sometimes running into hundreds of units. Many also give a history of taking weekly intramuscular injections of triamcinolone for several weeks or small doses of oral prednisolone, methylprednisolone or betamethasone for weeks to months. Many are overweight with truncal obesity and have striking striae (often in areas away from the sites of application of creams), hypopigmentation, telangiectasias, acneiform eruptions, local hypertrichosis and sometimes hirsutism [Figure 29]. Their 8 am and 4 pm serum cortisol levels are often very low, even less than 1 microliter per decaliter.70 Further studies are needed to quantify the proportion of patients so affected and the amount/duration of application of topical steroids to induce this phenomenon.

- Exogenous Cushing’s syndrome presenting with central obesity and broad striae, due to the application of topical steroids in a patient with tinea corporis

Stopping steroid creams and instituting appropriate antifungal therapy is recommended in these patients. In our observation of a limited number of cases, the serum cortisol levels then return to normal within 3 to 5 months. The infection in such cases may take a much longer time to fully clear despite appropriate treatment.71 We have had some patients needing treatment for 6–9 months before the infection finally resolved.

Characteristics of itch

Itching is one of the cardinal features of superficial dermatophytosis. It is graded severe in studies and can be very bothersome for adults and children alike. Patients complain of paroxysms of pruritus lasting for a few minutes a few times a day; some have it for longer periods. Another common symptom is ‘burning and itching.” In many cases, it gets aggravated by sweating, heat, hot water and after disrobing (atmokinesis), and can disturb sleep.72 A significant number of patients complain of nocturnal exacerbation of pruritus.73 Some fully treated patients complain of persistent itching which is often due to xerosis or impaired barrier function due to scratching and topical corticosteroid abuse. Topical antifungal agents like luliconazole have been anecdotally observed by many dermatologists to cause xerosis which can contribute to itching.

Change in the quality of life of patients

Superficial dermatophytosis is now to be viewed like other chronic and recurrent disorders because of its altered nature. The disease is now seen to have a significant bearing on the quality of life, emotions and personal relationships of affected individuals. It is the experience of dermatologists that many patients with chronic recalcitrant dermatophytosis develop feelings of hopelessness, shame and anger; a minority even express suicidal ideation. It is important to give adequate time to each patient, understand disease impact, and educate the patient about the disease, its management and prognosis in order to improve adherence to treatment and hence their quality of life.19

Financial impact

Though dermatophytosis in the current context does not spare any socioeconomic group, it is a common observation that chronic widespread dermatophytosis often affects those from the lower socioeconomic strata of society. A majority of these patients have multiple, similarly afflicted household contacts, resulting in a magnification of the financial burden of treatment. Such patients usually start with self-treatment and are later advised inappropriate medication (including steroid-containing creams) by non-dermatologists or unqualified individuals. The treatment continues with little or no benefit, compelling the patient to finally visit a dermatologist. Oral antifungals like itraconazole and topical molecules like luliconazole, sertaconazole, oxiconazole, amorolfine and ciclopirox olamine are currently preferred by dermatologists. They are perceived as more efficacious but are also much more expensive than the older antifungal drugs and are a significant financial burden to the patient, especially when multiple family members are affected. Cheaper brands manufactured by companies with uncertain credentials may lack efficacy, necessitating multiple visits to dermatologists and adding to the financial burden. In widespread disease, extensive application of the newer topical antifungals listed above is inconvenient and expensive. Patients often buy less than the required quantity to cut costs and discontinue treatment upon getting symptomatic relief. Other affected members of the household also may use these medications erratically. Such erratic treatment ironically results in their spending larger amounts of money over long periods. This particular patient population harbors smoldering, inadequately treated tinea that becomes an important pool of infection in the community.74

Conclusion

The epidemiology and clinical presentations of superficial dermatophytosis in India have undergone a sea change. This importantly includes the rather abrupt change from the Trichophyton rubrum to Trichophyton mentagrophytes as the predominant species in less than a decade. The disease now occurs irrespective of climatic changes, age, sex and educational or socioeconomic status, and is notable for its unprecedented high rate of transmission amongst family members and close contacts. There is a change in the morphology of individual lesions with varying degrees of inflammation, and a significant number of cases present with steroid-modified dermatophytosis. Despite many years of discussion and documentation of the adverse role of topical steroid containing fixed-dose combination creams, these irrational and often hazardous creams continue to be freely available in the market and are being abused by patients.

There is a stark increase in chronic, recurrent and relapsing dermatophytosis that impairs the quality of life due to severe pruritus. The disease also has financial implications for families with multiple affected members.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Emergence of terbinafine resistant Trichophyton mentagrophytes in Iran, harboring mutations in the squalene epoxidase (SQLE) gene. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:845-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spread of terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton mentagrophytes type VIII (India) in Germany: The tip of the iceberg? J Fungi (Basel). 2020;6:207.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(Suppl 4):2-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The current Indian epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes: A molecular study. Mycoses. 2019;62:336-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The great Indian epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis: An appraisal. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:227-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicomycological study of 150 cases of dermatophytosis in a tertiary care hospital in South India. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:322-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mycological pattern of dermatomycoses in a tertiary care hospital. J Trop Med. 2015;2015:157828.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological and clinical pattern of dermatomycoses in Rural India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 33:134-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytes in a tertiary care Centre in Northwest India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:194.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recurrent dermatophytosis: A rising problem in Sikkim, a Himalayan state of India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2017;60:541-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicomycological study of dermatophytic infections and their sensitivity to antifungal drugs in a tertiary care center. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:436-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A prospective study of the epidemiological and clinical patterns of recurrent dermatophytosis at a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:678-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Profile of dermatophytosis in a tertiary care center. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:490-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden of chronic dermatophytosis in a tertiary care hospital: Interaction of fungal virulence and host immunity. Mycopathologia. 2018;183:951-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutation in the squalene epoxidase gene of Trichophyton interdigitale and Trichophyton rubrum associated with allylamine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e02522-17.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for chronic and chronic-relapsing tinea corporis, tinea cruris and tinea faciei: Results of a case-control study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:197-200.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changing trend of superficial mycoses with increasing nondermatophyte mold infection: A clinicomycological study at a tertiary referral center in Assam. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:261-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The menace of superficial dermatophytosis on the quality of life of patients attending referral hospital in Eastern India: A cross-sectional observational study. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:262-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility patterns of clinical dermatophytes following CLSI and EUCAST guidelines. J Fungi (Basel). 2017;3:17.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and prevalence of dermatophytosis in and around Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:695-700.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicomycological study of dermatophytosis in South India. J Lab Physicians. 2015;7:84-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A clinico-mycological study of dermatophytoses in Goa, India. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:297-301.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological studies on dermatophytosis in human patients in Himachal Pradesh, India. Springerplus. 2014;3:134.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mycological pattern of dermatophytosis in and around Shimla hills. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:268-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinico-microbiological study of dermatophytosis in a tertiary-care hospital in North Karnataka. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:264-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A clinicomycological study of cutaneous mycoses in Sawai man singh hospital of Jaipur, North India. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:593-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The etiology of dermatophytosis; shift from Trichophyton mentagrophytes to Trichophyton rubrum 1935-1954. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:66-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:335-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A clinical and mycological study of dermatophytic infections. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:262-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of immune evasion in fungal pathogens. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:668-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenesis of dermatophytoses. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:259-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fungal strategies for overcoming host innate immune response. Med Mycol. 2009;47:227-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The interplay among Th17 and T regulatory cells in the immune dysregulation of chronic dermatophytic infection. Microb Pathog. 2020;139:103921.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives on misidentification of Trichophyton interdigitale/Trichophyton mentagrophytes using internal transcribed spacer region sequencing: Urgent need to update the sequence database. Mycoses. 2018;62:11-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The menace of chronic and recurrent dermatophytosis in India: Is the problem deeper than we perceive? Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:73-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerging atypical and unusual presentations of dermatophytosis in India. Clin Dermatol Rev. 2017;1(S1):12-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A closer look at the term tinea incognito: A factual as well as grammatical inaccuracy. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:219-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The rising menace of steroid abuse cascading from tinea incognito to erythroderma. J Evol Res Dermatol Venereol. 2016;2:4-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenesis of dermatophytosis. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:267-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinea pseudoimbricata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:344-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinea pseudoimbricata as a unique manifestation of steroid abuse: A clinico-mycological and dermoscopic study from a tertiary care hospital. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:422-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of corticosteroid-modified tinea: Study of 100 cases in a rural tertiary care teaching hospital of Western Uttar Pradesh, India. J Dermatol Cosmetol. 2018;2:64-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An unusual presentation of tinea cruris with bullous lesions. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:224-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupuserythematosus-like eruption induced by Trichophyton mentagrophytes infection. Dermatology. 2003;206:303-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atypical cases of Microsporum canis infection in the adult. Mycopathologia. 1981;74:181-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atypical features of tinea in newborns. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emergence of recalcitrant dermatophytosis in India. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:250-1.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Disseminated dermal Trichophyton rubrum infection-an expression of dermatophyte dimorphism? J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1168-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case report. Rosacea-like tinea incognito Mycoses. 2002;45:135-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unusual clinical manifestations caused by Trichophyton rubrum-atypical “rubrophytoses”. Hautarzt. 1989;40:364-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A distinct clinicopathological presentation of cutaneous dermatophytosis mimicking autoimmune blistering disorder. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:412-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Male genital dermatophytosis-clinical features and the effects of the misuse of topical steroids and steroid combinations-an alarming problem in India. Mycoses. 2016;59:606-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Involvement of little discussed anatomical locations in superficial dermatophytosis sundry observations and musings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11:419-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two cases of tinea ciliaris with blepharitis due to Microsporum audouinii and Trichophyton verrucosum and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2014;57:577-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A mycological study of clinically normal nails and waistbands and their role as sources of infection in patients with tinea corporis. Int J Res Dermatol. 2019;5:239-42.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tinea of vellus hair: An indication for systemic antifungal therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:603-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can dermoscopy serve as a diagnostic tool in dermatophytosis? A pilot study. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:530-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The immunocompromised district in dermatology: A unifying pathogenic view of the regional immune dysregulation. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:569-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinea confined to tattoo sites-an example of Ruocco's immunocompromised district. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:739-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varicella and herpes zoster appearing over sites of tinea corporis, hitherto unreported examples of immunocompromised districts: A case series. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:758-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf's isotopic response: Large annular polycyclic lichen planus occurring on healed lesions of dermatophytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:355-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclerosing and atrophying conditions In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, eds. Pediatric Dermatology (2nd ed). New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. p. :897.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pseudoedematous striae: An undescribed entity. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13754.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Study of reservoir effect of clobetasol propionate cream in an experimental animal model using histamine-induced wheal suppression test. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:329-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Systemic side-effects of topical corticosteroids. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:460-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case 1-management protocol in clinical practice In: Sardana K, Khurana A, Garg S, Poojary S, eds. IADVL Manual on Management of Dermatophytosis (1st ed). New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors; 2018. p. :147-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and clinical characteristics of itch in epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytoses in India: A cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:180-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life and psychological morbidity in patients with superficial cutaneous dermatophytosis. Mycoses. 2019;62:680-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emergence of recalcitrant dermatophytosis in India. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:718-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]