Translate this page into:

Thymocyte selection-associated high-mobility group box as a potential diagnostic marker differentiating hypopigmented mycosis fungoides from early vitiligo: A pilot study

Corresponding author: Dr. Marwa Yassin Soltan, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Abbasiya Square, Postal Code 11566, Cairo, Egypt. marwayassin@med.asu.edu.eg

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Ibrahim MA, Mohamed A, Soltan MY. Thymocyte selection-associated high-mobility group box as a potential diagnostic marker differentiating hypopigmented mycosis fungoides from early vitiligo: A pilot study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:819-25.

Abstract

Background:

Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides is a rare variant of mycosis fungoides that may mimic many benign inflammatory hypopigmented dermatoses, and as yet there is no identified marker to differentiate between them.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to study the expression of thymocyte selection–associated high-mobility group box (TOX) in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides and one of its inflammatory mimickers (early active vitiligo) to assess its potential as a differentiating diagnostic marker.

Methods:

A case–control study was done using immunohistochemical analysis of TOX expression in 15 patients with hypopigmented mycosis fungoides and 15 patients with early active vitiligo. Immunohistochemical analysis was done via a semi-quantitative method and an image analysis method.

Results:

Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides showed a statistically significant higher expression of TOX than early active vitiligo. The expression of TOX was positive in a majority of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides cases (14 cases, 93.3%), while only one case (6.7%) of vitiligo was weakly positive. TOX also displayed 93.3% sensitivity and specificity, with a cut-off value of 1.5.

Limitations:

This was a pilot study testing hypopigmented mycosis fungoides against only a single benign inflammatory mimicker (early vitiligo). Other benign mimickers were not included.

Conclusion:

Our findings showed that TOX expression can differentiate hypopigmented mycosis fungoides from early active vitiligo which is one of its benign inflammatory mimickers, with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity.

Keywords

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

hypopigmented mycosis fungoides

oncogenesis

thymocyte selection–associated high-mobility group box

TOX

vitiligo

Introduction

Mycosis fungoides is the most common variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Classic mycosis fungoides was first described by Alibert Bazin; after that, multiple variants have been described.2 Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides is considered a rare variant; however, it is common among Arabs and other darker skinned populations.3 Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides was found in 16% of patients presenting with hypopigmented lesions of the trunk in a cohort of Egyptian patients.4 The main diagnostic pitfall of this variant is its great resemblance to other inflammatory hypopigmented dermatoses. This difficulty in diagnosis warrants searching for a diagnostic marker to differentiate this condition from its mimickers.

Thymocyte selection–associated high-mobility group box (TOX) factor represents a part of the superfamily of high-mobility group box proteins acting as regulators of gene expression through modifying the chromatin structure.5 It has an important role during lymphocyte development and is involved in the switch of CD4+CD8+ precursors to CD4+ T cells in the thymus. However, it is downregulated after exiting from the thymus.6

TOX was found to be aberrantly expressed in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, and it can be considered a potential marker for the histological diagnosis of early-stage classical mycosis fungoides.7-9 Nevertheless, data on TOX expression and its significance in other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas such as hypopigmented mycosis fungoides are minimal.

Methods

The study was conducted on patients attending the cutaneous lymphoma clinic at El Demerdash Hospital, Cairo, Egypt and was approved by the research ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University. We included 15 patients with hypopigmented mycosis fungoides and 15 age- and sex-matched controls with early active vitiligo. The activity of vitiligo patients was evaluated according to the Vitiligo Disease Activity Score (VIDA), which is a 6-point scale (from −1 to +4), where higher VIDA scores indicate recent activity. We included active vitiligo patients with VIDA +3 (activity between 6 weeks to 3 months) and VIDA +4 (activity within 6 weeks).10 Vitiligo patients were diagnosed by clinical, Wood’s light examinations, and histopathological criteria described by El-Darouti et al.11 Vitiligo cases, 13 known vitiligo patients with recent disease activity and 2 new cases presenting with both depigmented and hypopigmented skin lesions, were recruited from the vitiligo clinic. All patients (hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, vitiligo) were newly diagnosed or off treatment for at least 3 months. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides patients were recruited from the cutaneous lymphoma clinic and diagnosed based on the algorithm for the diagnosis of early mycosis fungoides12 and staged according to Olsen et al.13 Punch skin biopsies (4 mm) were taken from the skin lesions of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides cases and the active edge of early hypopigmented lesions in active vitiligo controls, and 5 μm sections were prepared for routine histology and immunostaining for TOX. CD4/CD8 immunohistochemical staining was done for hypopigmented mycosis fungoides cases using the avidin–biotin immunoperoxidase complex technique.14 The antibodies used included the following: TOX (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; Cat No. HPA018322, 1:500), CD4 (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA; Cat No. 790-4423), CD8 (Ventana, Tucson, Arizona, USA; Cat No: 790-4460), and appropriate Histostain-SP kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA; Cat No: 95-9943). The designation of cases as CD4+ or CD8+ was based on the predominantly expressed marker.

Assessment of TOX immunostaining was done semi-quantitatively as described by Yu et al.15 Staining was considered negative when there were <10% positive cells, and positive staining if >10% of cells were positive (weak positive if 10%–50% positive cells and strong positive staining if >50% positive cells).

All sections were analyzed by a single pathologist who was blinded to the diagnosis of the examined sections. The analysis was further confirmed by the image analysis technique which was done using an image analyzer Leica Q win V.3 program connected to a Leica DM2500 microscope (Wetzlar, Germany). For each specimen, three different captured non-overlapping high-power fields were taken to measure area percentage of positive specific TOX immunostaining.

Statistical analysis of the data was done. Student’s t, Mann– Whitney, Chi-square, and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare variables. Spearman’s correlation was used to assess the correlation between variables. The receiver operating characteristic curve was used to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of mean area percentage by image analysis. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used in all the tests. All statistical procedures were carried out using SPSS version 20 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

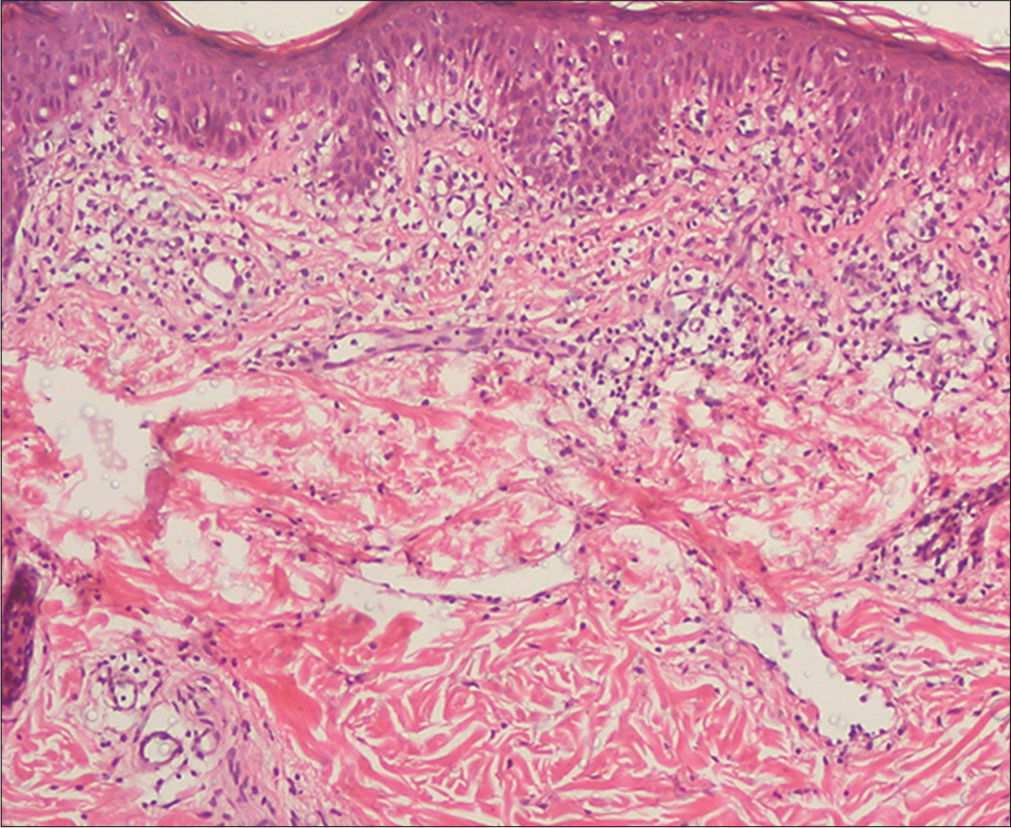

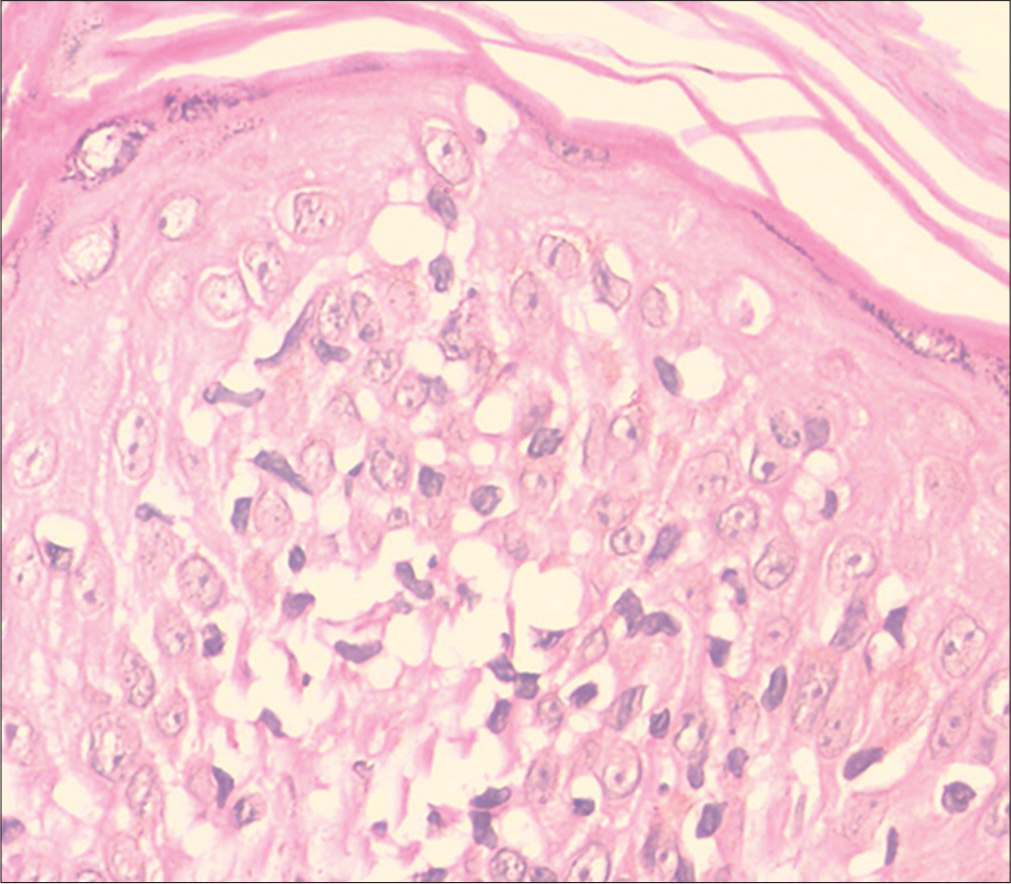

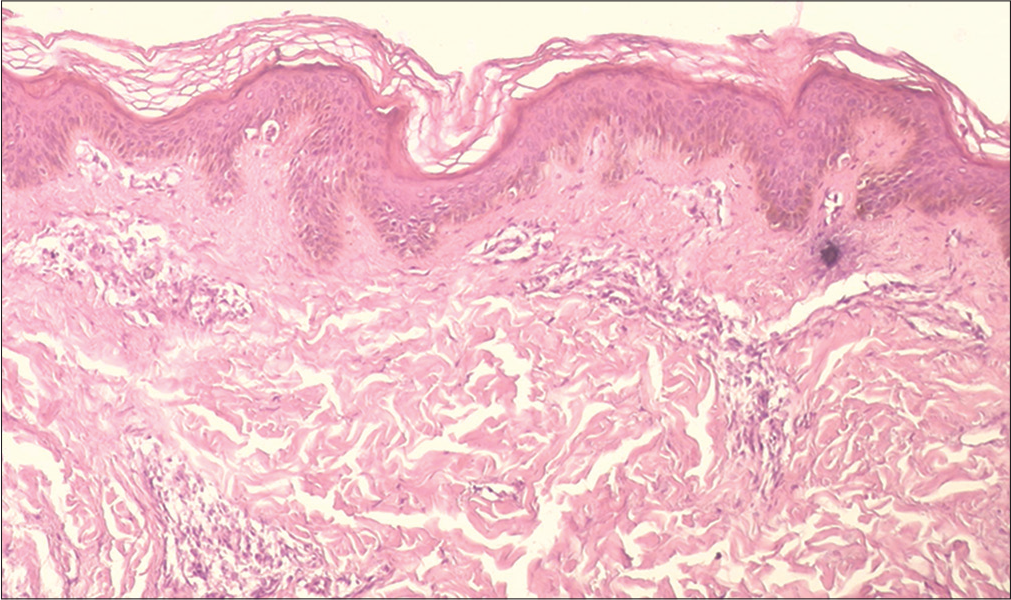

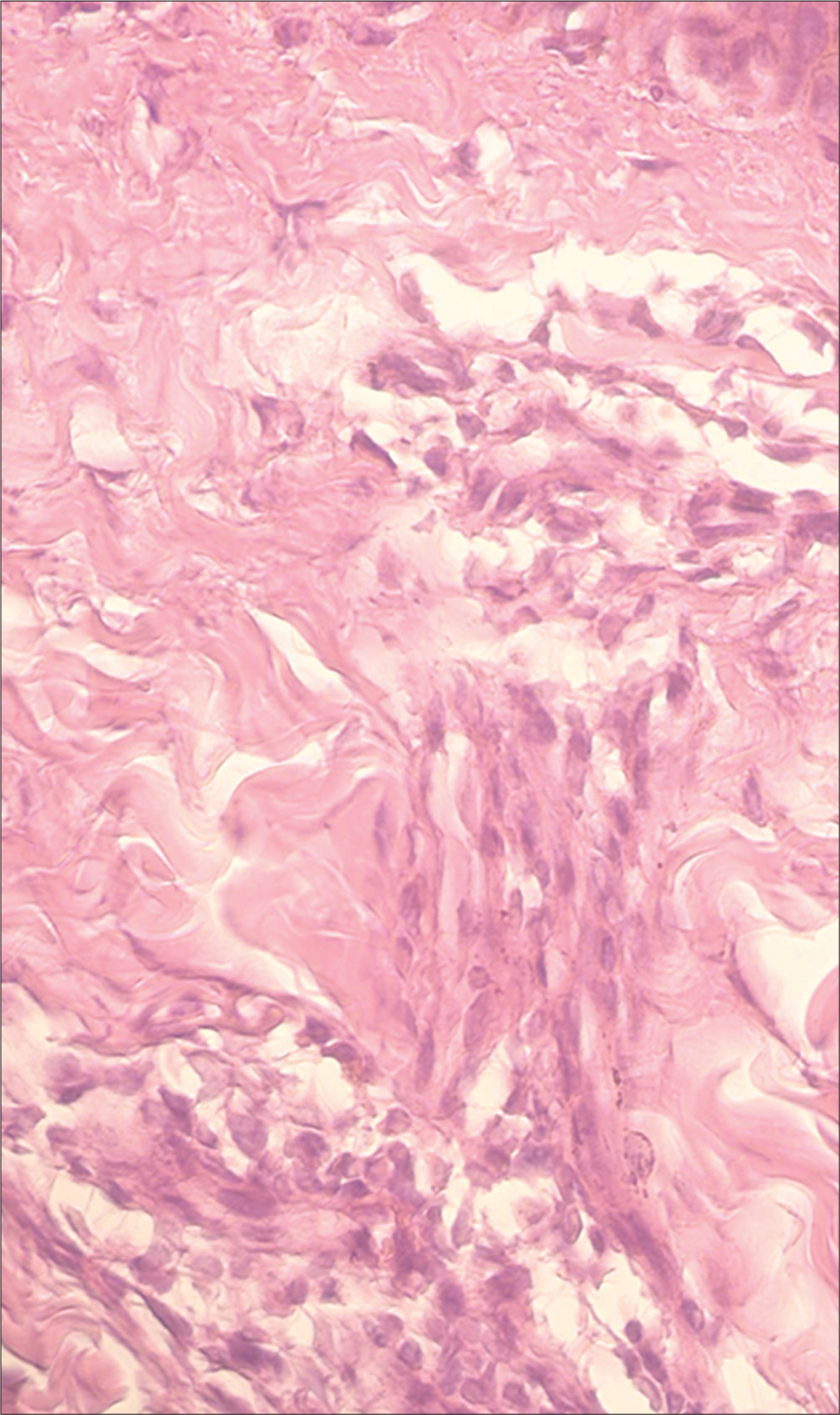

The mean age among hypopigmented mycosis fungoides cases was 21.8 ± 11.8 years, and most were males (12 patients, 80%). The mean age at the time of disease onset was 18.1 ± 10.5 years with a mean duration of 3.7 ± 3.6 years. Thirteen patients (87%) had lesions on sun-protected areas. Ten patients (67%) were staged as IIA, while five patients (33%) were at stage I. Interface type of epidermotropism was found in eight patients (53%), while the pagetoid type of epidermotropism was found in seven patients (47%). Eleven patients (73%) had a predominant CD8+ immune profile, while the rest (four patients, 27%) showed a predominant CD4+ profile. In the vitiligo cases, histopathological sections from patch margins showed mild to moderate superficial and mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate in all cases.

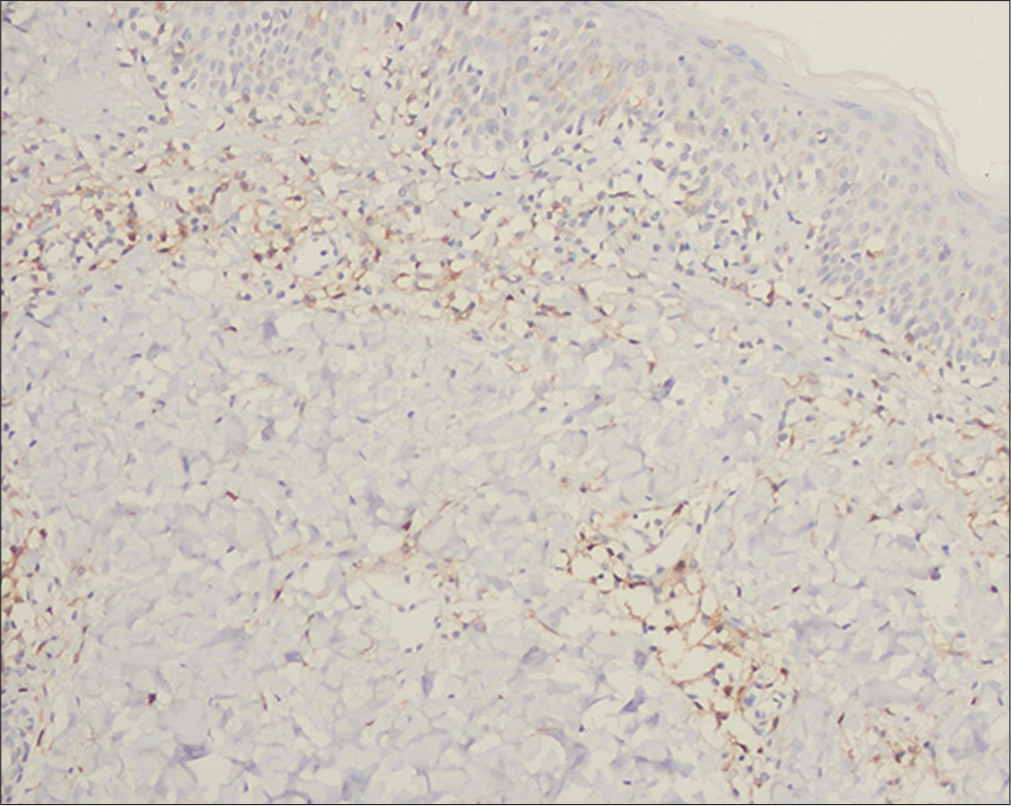

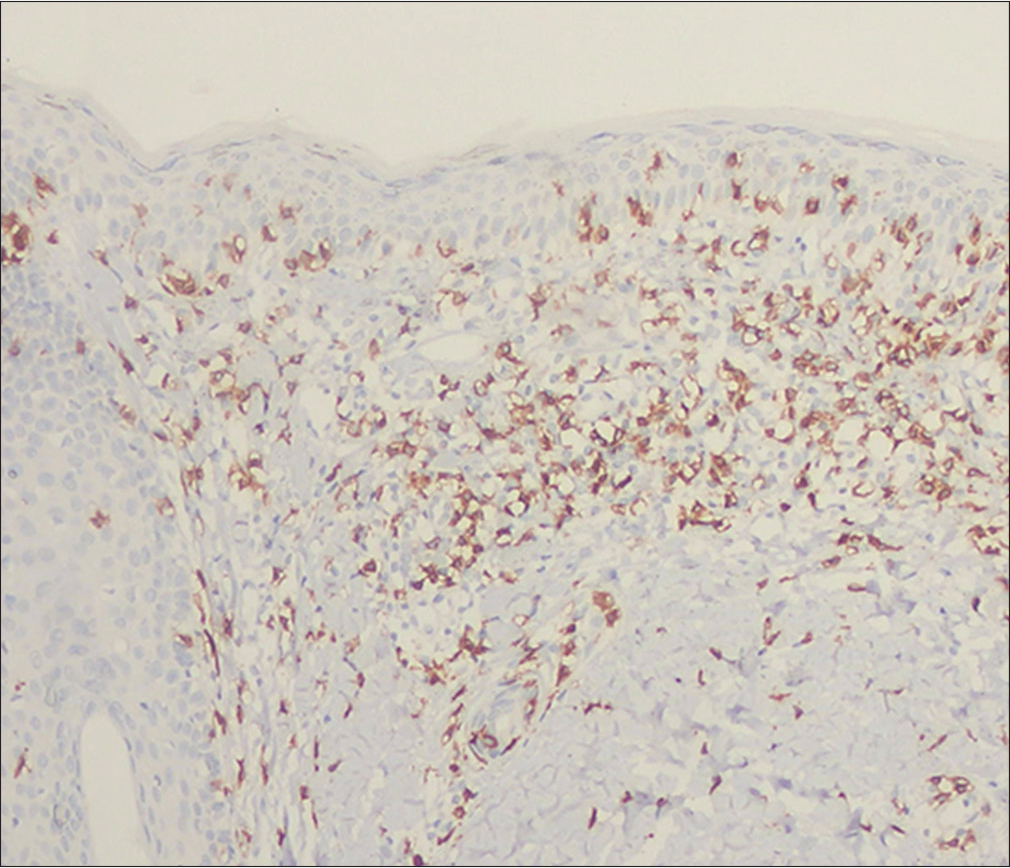

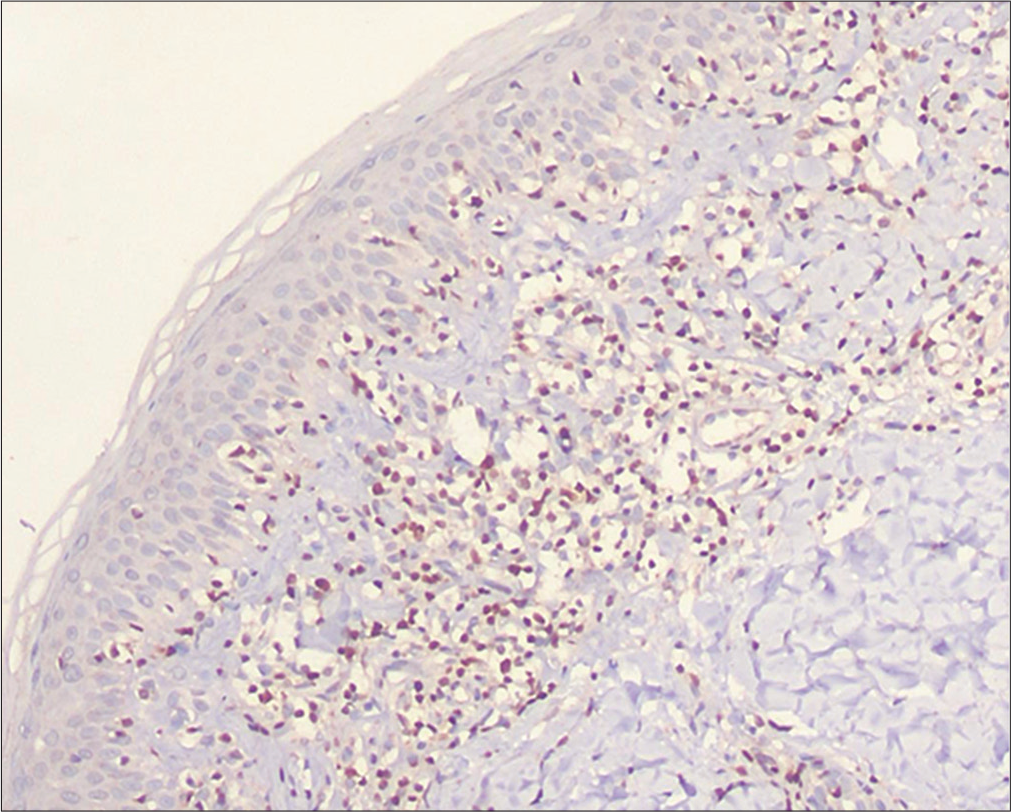

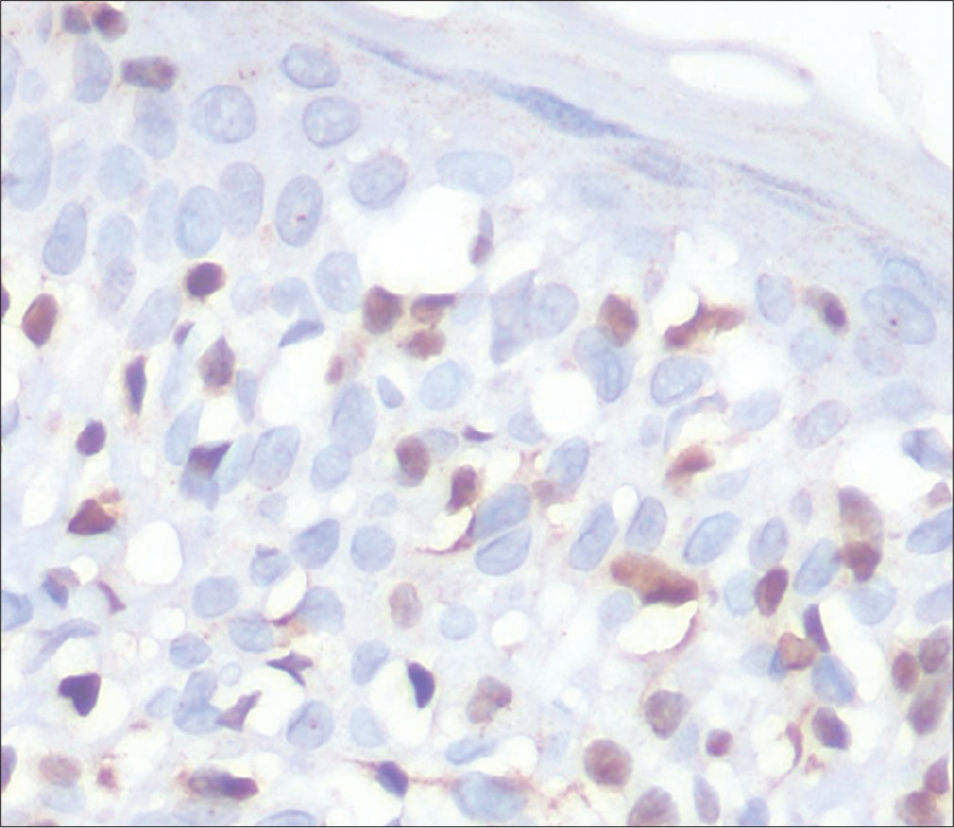

TOX expression with nuclear staining of the lymphocytes was significantly higher in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides than in the active vitiligo lesions [Figures 1 and 2]. By semi-quantitative analysis, 14 mycosis fungoides patients (93.3%) were positive (66.7% showed strong positivity and 26.6%, weak positivity), while only 1 patient (6.7%) showed a negative result. In contrast, only 1 patient (6.7%) from amongst the vitiligo controls showed weak positivity for TOX, while 14 patients (93.3%) were negative. By image analysis, the area percentage was 4.1 ± 2.7 and 1 ± 0.5 in cases and controls, respectively, with P < 0.001 [Table 1].

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Asymptomatic hypopigmented patches on the back of a 25-year-old female patient

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Histopathology showed epidermotropism and upper/mid-dermal moderate perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (H and E, ×100)

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Moderate epidermotropism and cellular atypia (H and E, ×400)

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Negative immunostaining of the epidermotropic lymphocytes for CD4, a few dermal lymphocytes are positive (immunostain, ×100)

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Positive immunostaining of the epidermotropic and dermal lymphocytes for CD8 (immunostain, ×100)

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Positive immunostaining of the epidermotropic and dermal lymphocytes for thymocyte selection–associated high-mobility group box (TOX) (immunostain, ×100)

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Positive immunostaining of the epidermotropic lymphocytes for thymocyte selection–associated high-mobility group box (TOX) (immunostain, ×400)

- Vitiligo: hypopigmented patches on the leg of an 8-year-old male child

- Vitiligo: Histopathology showed superficial and mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate (H and E, ×100)

- Vitiligo: Histopathology showed superficial and mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate (H and E, ×400)

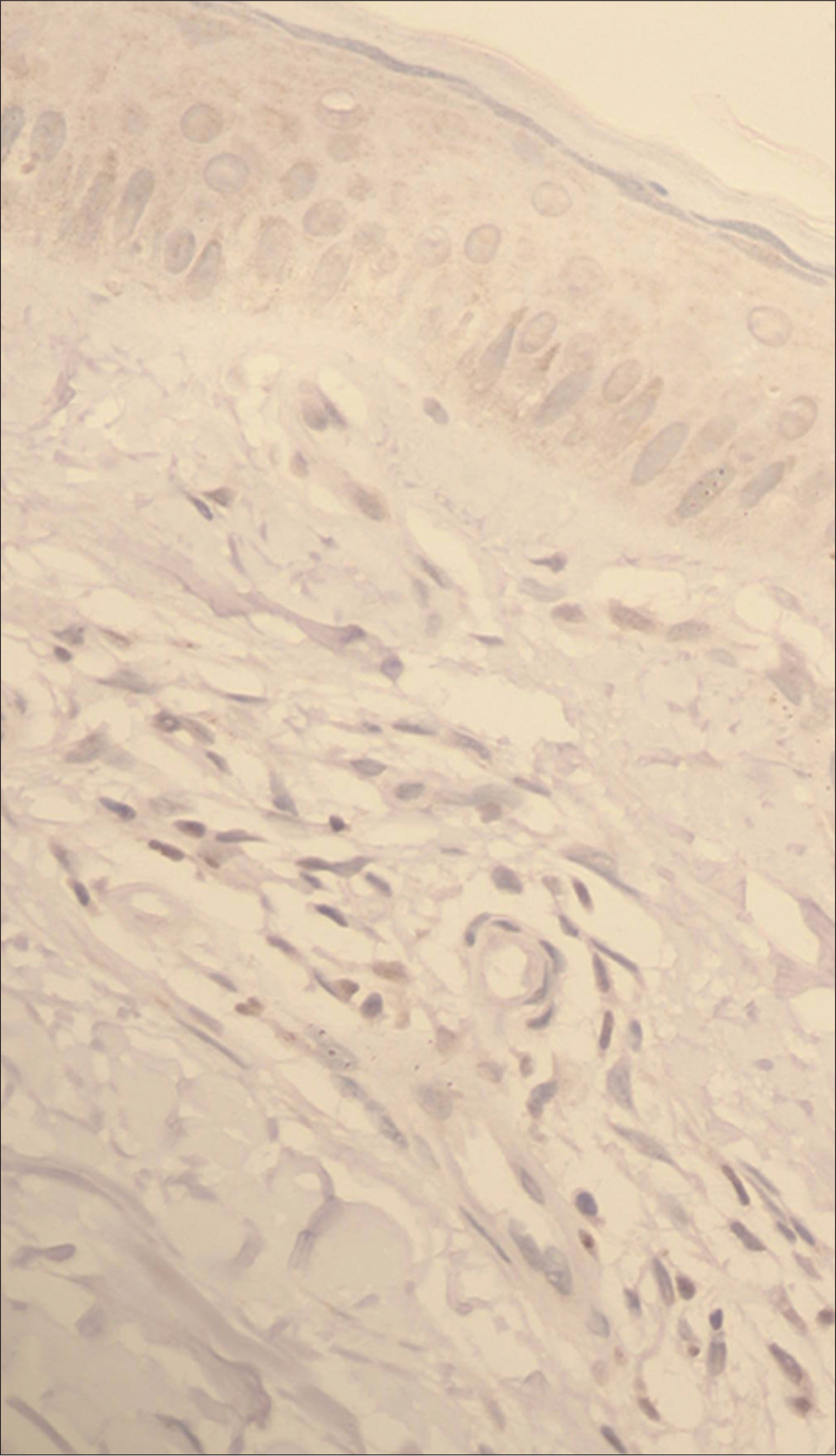

- Vitiligo: Negative immunostaining for thymocyte selection– associated high-mobility group box (TOX) (immunostain, ×100)

- Vitiligo: Negative immunostaining for thymocyte selection–associated high-mobility group box (TOX) (immunostain, ×400)

| Factors | Group | Test of significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMF | Early vitiligo | P | Significant | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 21.8±11.8 | 26.5±7.5 | 0.106* | NS |

| Median (IQR) | 17 (12-30) | 25 (20-32) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 12 (80) | 8 (53.3) | 0.121† | NS |

| Female | 3 (20) | 7 (46.7) | ||

| TOX expression | ||||

| Semi-quantitative, n (%) | ||||

| Negative | 1 (6.7) | 14 (93.3) | 0.001‡ | HS |

| Weak positive | 4 (26.6) | 1 (6.7) | ||

| Strong positive | 10 (66.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Semi-quantitative, n (%) | ||||

| Negative | 1 (6.7) | 14 (93.3) | 0.001† | HS |

| Positive | 14 (93.3) | 1 (6.7) | ||

| Image analysis | ||||

| Area (%) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 4.1±2.7 | 1±0.5 | <0.001* | HS |

| Median (IQR) | 3.3 (2.3-6.2) | 1.2 (0.8-1.2) | ||

IQR: interquartile range; NS: nonsignificant; HS: highly significant

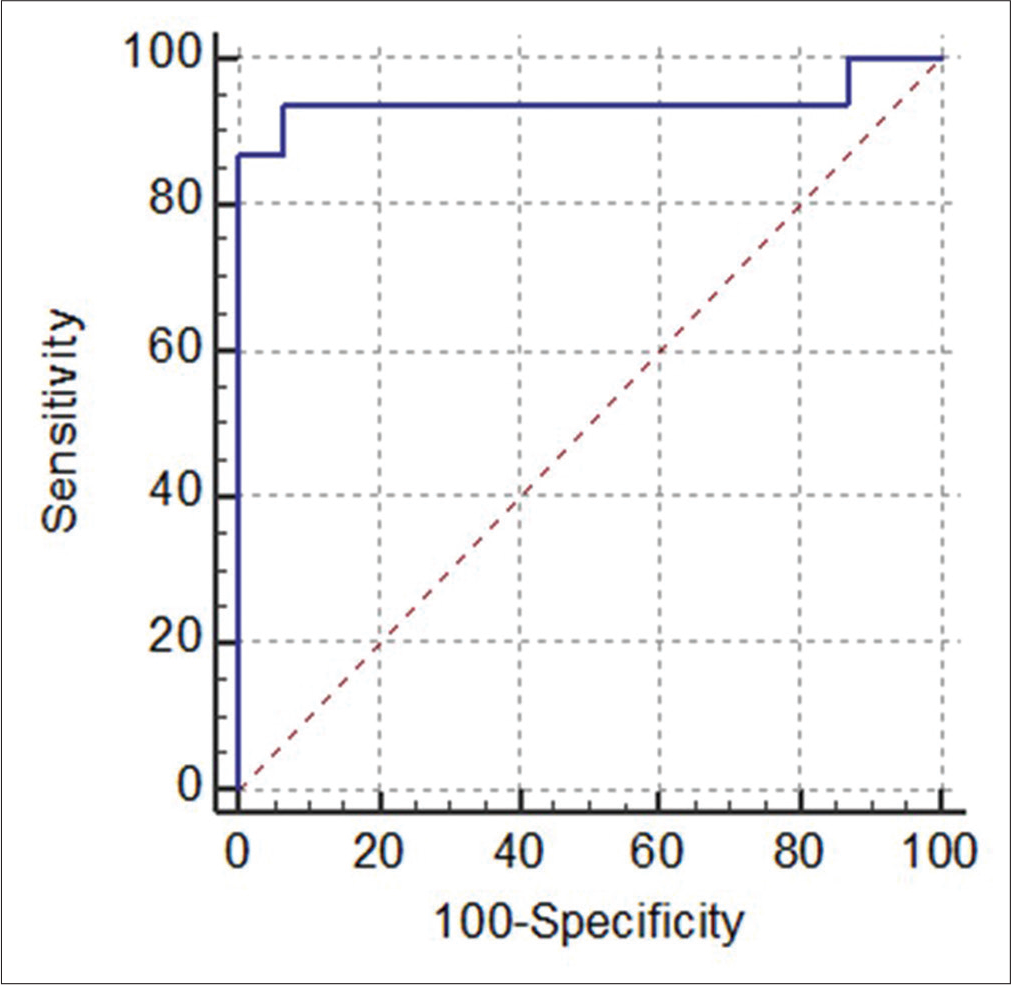

TOX expression was 93.3% sensitive and specific in differentiating cases from controls with a cut-off value of 1.5 in the image analysis study [Table 2 and Figure 3].

| Cutoff level | AUC (CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | P | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >1.5 | 0.9 (0.8-0.99) | 93.3 | 93.3 | 93.3 | 93.3 | 0.001 | HS |

CI: confidence interval; AUC: area under the curve; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; HS: highly significant

- Receiver operating characteristic curve showing 93.3% sensitivity and specificity for thymocyte selection–associated high-mobility group box (TOX) expression (by image analysis) differentiating hypopigmented mycosis fungoides from controls with area under the curve: 0.93

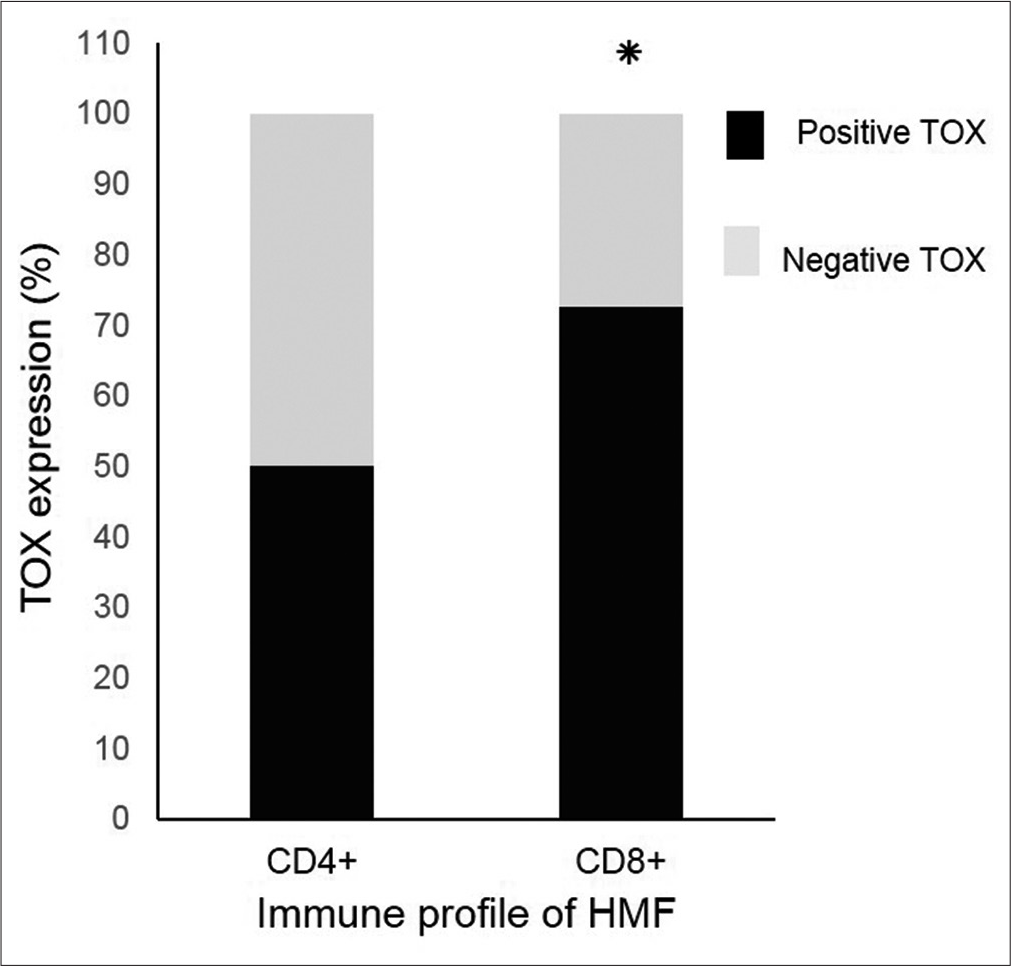

No significant difference was found in TOX expression between cases with a predominant CD4 immune profile and those with a predominant CD8 profile within the mycosis fungoides group [Figure 4]. There were also no significant differences found in TOX expression within the case group in relation to the age and sex of patients, site of the biopsied lesion, stage of mycosis fungoides, epidermotropism type, duration of disease, and age at the time of disease onset (data not shown).

- Thymocyte selection–associated high-mobility group box (TOX) expression in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides regardless of CD4/CD8 immune profile by semi-quantitative analysis (*P = 0.56 using Fishers exact test)

Discussion

Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides was first reported by Ryan et al. in 1973.16 Clinically it presents with asymptomatic macular lesions with variable degrees of hypopigmentation or even vitiligo-like depigmentation and of variable patch sizes ranging from raindrop-sized to large patches. The great variability of clinical features has led to a long list of differential diagnoses of hypopigmented disorders which may mimic this condition. Though it has a relatively good prognosis when compared with classic mycosis fungoides/ Sézary syndrome, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides is a malignant neoplastic disease with possible mortality which necessitates early diagnosis and proper staging, and thus a clear distinction from its mimickers.17 Inflammatory vitiligo is the foremost of these mimickers due to its close similarity both clinically and histopathologically, and hence, researchers have tried to describe distinctive histological differentiating features.11,18 Diagnosis of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides is made mainly by clinicopathologic correlation; however, the histological features may be insufficient in early lesions and repeated biopsies may be required.17 Even studies of T-cell receptor gene rearrangement might be inconclusive as monoclonality may be detected in only 50% of patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Further confusion may arise since some benign dermatoses including active vitiligo may exhibit monoclonality.18 Therefore, new differentiating markers are certainly needed.

TOX is considered as a probable marker for the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides owing to its higher expression in this condition than in benign inflammatory dermatoses, and its expression increases with disease progression.15 TOX is linked to mycosis fungoides tumorigenesis and progression in a multifaceted way. TOX enhances neoplastic T-cell proliferation and migration through the AKT pathway and promotes the cell cycle by suppressing cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (p27 and p57).7,15 TOX also suppresses the tumor suppressor gene RUNX38 and is a target gene of miR-223 which promotes cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.19

This first report comparing TOX expression in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides to active vitiligo reveals that TOX is significantly expressed in the former and can differentiate it from early lesions of active vitiligo with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity. However, this pilot study examined one inflammatory mimicker only (active vitiligo) and other benign mimickers were not included. Some reports have linked TOX expression in mycosis fungoides with the CD4+ immune profile.9,20,21 However, Schrader et al. outlined that TOX expression is not limited to CD4+/CD8−.22 It was found in 97% in the CD4+/CD8− phenotype, 63% in the CD4−/ CD8+ phenotype, and 63% in CD4−/CD8−. They proposed that the expression of TOX in CD8+ lymphocytes represents an aberrant expression due to dedifferentiation of tumor cells. Similarly, we found that positivity to TOX in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides occurred regardless of the CD4/CD8 immune profile indicating that TOX is a potential diagnostic marker even in instances with a predominant CD8+ phenotype.

Conclusion

TOX is a promising diagnostic marker in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides which can differentiate it from early active vitiligo, one of its inflammatory mimickers, with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity. TOX appears to be expressed among hypopigmented mycosis fungoides cases regardless of the lesional immune profile.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Prof. Shadia Mabrouk, professor of pathology, Ain Shams University, for her generous help with the pathological review.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathologic variants of mycosis fungoides. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:192-208.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Profile of mycosis fungoides in 43 Saudi patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:283-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frequency of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Egyptian patients presenting with hypopigmented lesions of the trunk. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:834-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOX: An HMG box protein implicated in the regulation of thymocyte selection. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:272-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The many roles of TOX in the immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:173-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evidence of an oncogenic role of aberrant TOX activation in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:1435-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOX expression and role in CTCL. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1497-502.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOX expression in different subtypes of cutaneous lymphoma. Arch Dermatol Res. 2014;306:843-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of the Köbner phenomenon with disease activity and therapeutic responsiveness in vitiligo vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:407-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiligo vs. hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (histopathological and immunohistochemical study, univariate analysis) Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:17-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and sezary syndrome: A proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Blood. 2007;110:1713-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: A comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981;29:577-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOX acts an oncological role in mycosis fungoides. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117479.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can mycosis fungoides begin in the epidermis? A hypothesis. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:419-29.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: A review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inflammatory vitiligo versus hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in a 58-year-old Indian female. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:321-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MiR-223 regulates cell growth and targets proto-oncogenes in mycosis fungoides/cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1101-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Two cases of CD8-positive hypopigmented mycosis fungoides without TOX expression. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e164-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOX as a diagnostic and prognostic marker for mycosis fungoides. J Egypt Womens Dermatol Soc. 2018;15:15-22.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- TOX expression in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: An adjunctive diagnostic marker that is not tumour specific and not restricted to the CD4(+) CD8(-) phenotype. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:382-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]