Translate this page into:

Topical corticosteroid-induced rosacea-like dermatitis: A clinical study of 110 cases

2 Christian Institute of Health Sciences & Research, Dimapur, Nagaland, India

Correspondence Address:

Sanjay K Rathi

143, Hill Cart Road, Siliguri - 734 001, West Bengal

India

| How to cite this article: Rathi SK, Kumrah L. Topical corticosteroid-induced rosacea-like dermatitis: A clinical study of 110 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:42-46 |

Abstract

Background: Prolonged and continuous use of topical steroids leads to rosacea-like dermatitis with variable clinical presentations. Aims: To study the various clinical presentations of patients with topical corticosteroid-induced rosacea-like dermatitis (TCIRD), who had a history of prolonged and repeated use of topical steroids for reasons other than the known disease entities. Methods: A total of 110 patients were enrolled for the study over a period of 2 years, excluding all those with the known disease entity in which topical steroids were commonly used. Detailed history which also included the source and the type of topical steroid use was taken along with clinical examination. Results: There were 12 males and 98 females with their age ranging from 18 to 54 years. The duration of topical steroid use ranged from 4 months to 20 years. The most common clinical presentation was diffuse erythema of the face. Most of the patients had rebound phenomenon on discontinuation of the steroid. The most common topical steroid used was Betamethasone valerate, which could be due to its easy availability and low cost. Conclusion: Varied clinical presentations are seen with prolonged and continuous use of topical steroids. The treatment of this dermatitis is difficult, requiring complete cessation of the offending steroid, usually done in a tapering fashion.Introduction

Topical corticosteroid-induced rosacea-like dermatitis (TCIRD) is an entity which starts after long and improper application of topical corticosteroid and the rebound phenomenon which appears after discontinuation of its use on the face. Numerous other terms have been used by various authors to describe this disease entity. [1],[2]

The main clinical presentations of TCIRD are papules, pustules, papulovesicles and sometimes nodules on diffuse erythematous and edematous background. Despite its resemblance to rosacea, TCIRD currently is not considered a variant of rosacea because rosacea is already a well-defined term and entity. [1],[2],[3] Despite the fact that TCIRD is commonly seen in the clinical settings, it is under-addressed in the literature. [2],[4]

The aim of this study is to know the various clinical presentations of TCIRD, where topical corticosteroids were used for reasons other than the known primary disease entities.

Methods

A total of 110 cases were included for the study over a period of 2 years from January 2007 to December 2008. A detailed history regarding duration of existing problem, steroid use, including the name of the molecule used and its duration, were noted down. History also included source and purpose of topical steroid used.

The patients were examined for various clinical lesions. Depending on the location of the eruption, they were divided into diffuse, malar, perioral and centrofacial. Skin scrapping for fungus (potassium hydroxide mount) was done in all the patients to exclude fungal infection, and also, ophthalmic check-up was done to rule out topical steroid induced side-effects. Based on the history and the clinical examination, all those patients suggestive of having rosacea, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis and contact dermatitis, prior to the use of the topical steroid, and also patients who had used two different molecules of topical steroid were excluded from the present study. Only those patients who developed the clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of TCIRD due to use of topical corticosteroid for cosmetic purpose including melasma and for nonspecific reason, were included in the study.

The diagnosis was based on clinical suspicion based on clinical examination, including a detailed patient history revealing topical steroid use and rebound phenomenon on stopping the same.

Results

Out of 110 cases, 12 were males and 98 were females. Their age ranged from 18 to 54 years. Duration of problem varied from 1 month to 20 years (between 1 and 6 months = 7; 6-12 months = 61; 1-2 years = 12; >2 years = 30 in number).

The minimum duration required to develop the dermatoses was 4 months and the maximum use was up to 20 years.

Out of 110 cases, the commonest topical corticosteroid used was Betamethasone valerate by 64 patients, followed by Mometasone furoate by 19 patients and Betamethasone dipropionate by 16 patients, while Clobetasole propionate was used by 6 and Fluocinolone acetonide was used by 5 of them. In 55.5% of patients, use of topical corticosteroid was suggested by their friends, 25.4% by chemists, 13.6% by beauticians, 4.6% by their relatives and 0.9% used it on doctors′ advice.

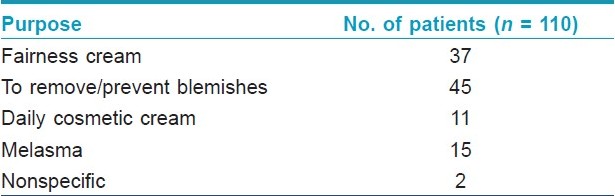

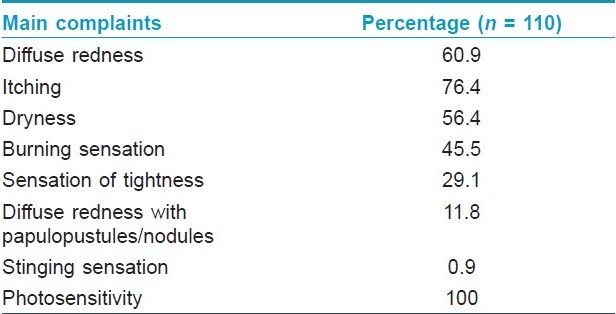

Out of 110 patients enrolled, 48 had diffuse and 40 had malar variety, while 20 showed centrofacial and 2 of them showed perioral pattern of the eruption. Basic purpose of starting topical corticosteroids and main complaints are shown in [Table - 1] and [Table - 2].

All the cases had history of exacerbation of their symptoms following sun exposure and rebound phenomenon on stopping the cream. General physical and systemic examinations including ophthalmic examination were normal in all. Routine laboratory parameters including skin scrapping for fungus were normal.

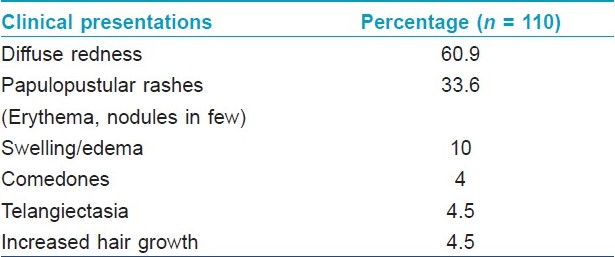

[Table - 3] shows the main clinical features of patients with TCIRD.

Clinical features

Based on the history and clinical examination, the primary lesions in the eruption were small red or skin colored papules or papulovesicles. When the papules cleared, they were replaced by more diffuse redness in the natural course of the eruptions. With the continuous use of topical steroids, the subjects finally presented with diffusely inflamed edematous skin [Figure - 1]. In some with diffuse erythema and/or telangiectasia, there were papules, pustules or even nodules [Figure - 2],[Figure - 3],[Figure - 4],[Figure - 5].

|

| Figure 1 :Diffuse erythema on face including on eye lids with scaling and swelling (diffuse pattern) |

|

| Figure 2 :Dense erythema with papulopustules and nodules on face |

|

| Figure 3 :Diffuse erythema with papulopustules, scaling and excoriated lesions (diffuse pattern) |

|

| Figure 4 :Erythema, scaling and papulopustules on malar area (malar pattern) |

|

| Figure 5 :Mild erythema, dryness and telangiectasia on malar area of face |

Discussion

Hydrocortisone was first described in 1951 for topical use and, subsequently, the super-potent steroids were introduced in 1974. With the introduction of super-potent topical steroids, a new dermatosis emerged, which was named variously by different workers. Initially, it was given the name light sensitive seborrheid, perioral dermatitis, rosacea-like dermatitis, steroid rosacea, steroid dermatitis resembling rocasea (in Latin: dermatitis rosaceiformis steroidica) and lastly steroid-induced rosacea-like dermatitis (SIRD). [1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10] Since there is no consensus regarding nomenclature, we prefer to use the term TCIRD since it indicates the morphology of lesion due to topical corticosteroid use.

The dermatosis so caused is due to the prolonged and improper use of topical steroid on the face. The patients all had good to magical response initially for whatever cosmetic reason it was initiated, but on continuation of the application, they started to develop rashes, and on stopping the drug, there was recurrence of rashes, i.e., rebound phenomenon. So, to prevent this effect, they resumed the use of the cream. The reason for consulting a doctor by most of them is that they found their skin problem no longer responding to the so called "magical effect" of the cream.

Basic purpose of starting the steroid cream in all of them was to look fairer, beautiful and free of so called "blemishes". We have seen in our study that the suggestions to use them were given by friends, relatives, pharmacy, beauty parlor and even doctors who had prescribed it without specific indications. It was found in this study that Betamethasone valerate was the most commonly used topical corticosteroid, may be due to this being the most cost-effective and easily available amongst all.

Perioral, diffuse and centrofacial are the main types described for steroid dermatitis resembling rosacea in literature. [1],[2] This study showed diffuse variety as the most common clinical presentation and even malar pattern presentation was also commonly seen in our scenario, which has not been described in the literature. Most of them had history of exacerbation of symptoms after sun exposure, probably due to atrophy and vasodilatation of the facial skin, caused by the prolonged use of topical steroid. There was no difference between the clinical presentations depending on the molecule of the topical steroid used. Surprisingly, none of them had any eye problems.

Steroids inhibit the release of a natural vasodilator called endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Prolonged used of topical steroids leads to vasoconstriction which in turn leads to buildup of multiple metabolites such as nitric oxide (a potent vasodilator). Once the steroid is discontinued, the vasoconstrictor effect ceases and the diameter of the blood vessels is enlarged beyond their original pre-steroid diameter because of the accumulation of the nitric oxide, which in turn exacerbates the erythema, burning sensation and the pruritus of TCIRD. [2],[11] The role of Demodex follicurum in the pathogenesis of TCIRD is controversial. [1],[12] It has been reported that the population of Demodex mites is increased in these patients, [13] and it is possible that by blocking the hair follicles, it can cause inflammation or allergic reaction or act as vectors for other microorganism. [14] Demodex mites are also present in healthy individuals and may have a pathogenic role only when present in high densities. [15]

The management of red face in dermatology is one of the most difficult therapeutic challenges to a dermatologist; very frequently, the patients suffer from very weak cutaneous barrier on the face and are intolerant to any topical treatment. In the treatment, discontinuation of topical steroid is essential, but this invariably leads to a flare up. [1] To prevent this, some authors have suggested using mild topical steroids in a tapering fashion. [1],[16],[17],[18] In our experience, less severe cases have improved with mild topical steroid used in a tapering fashion along with emollients, followed by complete cessation of the topical steroid. In severe cases, oral anti-inflammatory antibiotics, with or without topical metronidazole, need to be added to the treatment regime. This was also the experience of other authors. [1],[18],[19],[20] Most recently, the topical calcineurin antagonists such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have been used in the treatment which seems to offer quicker improvement and more rapid resolution of the condition. [2],[21],[22] So, they should be considered as alternative or adjuvant therapies for patients who do not respond to traditional treatment.

This dermatosis is very commonly seen in the clinical practice of a dermatologist, but still there are very few studies available in the literature. [2],[4],[8]

Conclusion

Prolonged and continuous use of topical steroid can cause "red face in dermatology" which presents clinically as diffused erythema with/without papules, pustules and sometimes nodules with telangiectasia. Treatment is difficult as there is rebound phenomenon with discontinuation of the topical steroid. Gradual tapering with complete cessation of the topical steroid and addition of oral anti-inflammatory antibiotics and/or topical antibiotics are usually recommended to get a good clinical result. The limitation of this study is the absence of histopathologic studies, which even though may not be diagnostic and specific, could have been done to rule out other pathologies. Also, contact dermatitis to topical steroids was not ruled out and so some patients with contact dermatitis to topical steroids may have been included in the study. This needs to be ruled out by doing patch test with topical corticosteroid series.

| 1. |

Ljubojeviae S, Basta-JuzbaSiae A, Lipozeneiae J. Steroid dermatitis resembling rosacea: Aetiopathogenesis and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2002;16:121-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Chen AY, Zirwas MJ. Steroid-induced rosacealike dermatitis: Case report and review of the literature. Cutis 2009;83:198-204.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, Drake L, Liang MH, Odom R, et al. Standard grading system for rosacea: Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;50:907-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Rathi S. Abuse of topical steroid as cosmetic cream: A social background of steroid dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol 2006;51:154-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Frumess GM, Lewis HM. Light sensitive seborrheid. AMA Arch Derm 1957;75:245-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Mihan R, Ayres S Jr. Perioral dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 1964;89:803-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Sneddon I. Iatrogenic dermatitis. Br Med J 1969;4:49.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Leyden S, Thew M, Kligman AM. Steroid Rosacea. Arch Dermatol 1974;110:619-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Zmegac ZJ, Zmegac Z. So-called perioral dermatitis. Lijec Vjesn 1976;98:629-38.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Sneddon I. Adverse effect of topical fluorinated corticosteroids in rosacea. Br Med J 1969;1:671-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Rapaport M, Rapaport V. Serum nitric oxide levels in "Red" patients: Separating corticosteroid-addicted patients from those with chronic eczema. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:1013-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Hoekzema R, Hulsebosh HJ, Bos JD. Demodicidosis or rosacea: What did we treat? Br J Dermatol 1995;133:294-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Bonnar E, Eustace P, Powell FC. The Demodex mite population in rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;26:443-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Roihu T, Kariniemi AL. Demodex mites in acne rosacea. J Cutan Pathol 1998;25:550-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Erbagci Z, Ozgoztasi O. The significance of Demodex follicurum density in rosacea. Int J Dermatol 1998;37:421-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Uehara M, Mitsuyoshi O, Sugiura H. Diagnosis and management of the red face syndrome. Dermatol Ther 1996;1:19-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Sneddon IB. The treatment of steroid-induced rosacea and perioral dermatitis. Dermatologica 1976;152:231-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Bikowski JB. Topical therapy for perioral dermatitis. Cutis 1983;31:678-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Coskey RJ. Perioral dermatitis. Cutis 1984;34:55-6, 58.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Veien NK, Munkvad JM, Neilsen AO, Niordson AM, Stahl D, Thormam J. Topical metronidazole in the treatment of perioral dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:258-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Goldman D. Tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of steroid-induced rosacea: A preliminary report. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:995-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Chu CY. An open-label pilot study to evaluate the safety and the efficacy of topically applied pimecrolimus cream for the treatment of steroid-induced rosacea-like eruption. J Eur Aca Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:484-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

9,185

PDF downloads

1,700