Translate this page into:

Transepidermal elimination of Mycobacterium leprae in histoid leprosy: A case report suggesting possible participation of skin in leprosy transmission

Correspondence Address:

Ashok Krishnarao Ghorpade

BK D-18, Sector 9, Bhilai, Chhattisgarh - 490 006

India

| How to cite this article: Ghorpade AK. Transepidermal elimination of Mycobacterium leprae in histoid leprosy: A case report suggesting possible participation of skin in leprosy transmission. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:59-61 |

Abstract

An Indian patient of histoid leprosy presenting de novo, having numerous solid staining bacilli inside the intact epidermis and eliminating bacilli from the intact and the eroded epidermis, is reported. The diagnosis, suggested by the clinical features, was confirmed histopathologically. This unusual report indicates possible participation of skin in leprosy transmission.Introduction

Though leprosy is slowly declining, the exact route of transmission of leprosy is unclear. Its transmission through the respiratory tract is commonly impressed upon, as compared to the skin route. However, the present case report possibly suggests the role of skin in leprosy disease transmission.

Case Report

A 56-year-old Indian male from Bhilai (Chhattisgarh state), an endemic area for leprosy, presented with a history of multiple asymptomatic skin lesions on the upper arms, hands, face and legs, of 3 month duration. There was no previous history of skin lesions/treatment, i.e., he presented de novo. The family members were normal.

Skin examination showed multiple skin colored, shiny, firm, non-tender nodules of size between 2 and 12 mm, abruptly arising over normal skin, over the forehead, medial aspect of both the hands, on upper arms, elbows, and the legs, with erosions and crusting over both the arms, elbows and legs [Figure - 1]a-c. There was hypoesthesia in the hands and feet (glove and stocking area) for thermal, touch and pain sensations after testing with hot and cold water, cotton-wool and pin prick; bilateral ulnar and lateral popliteal nerves were thickened. Systemic and eye examination were normal. There was no organomegaly or lymphadenopathy.

|

| Figure 1 :(a) Shiny intact and eroded histoid nodules on both the arms and back; (b) close-up view of shiny bigger intact and eroded histoid nodules on left upper arm and elbow and (c) over both the legs |

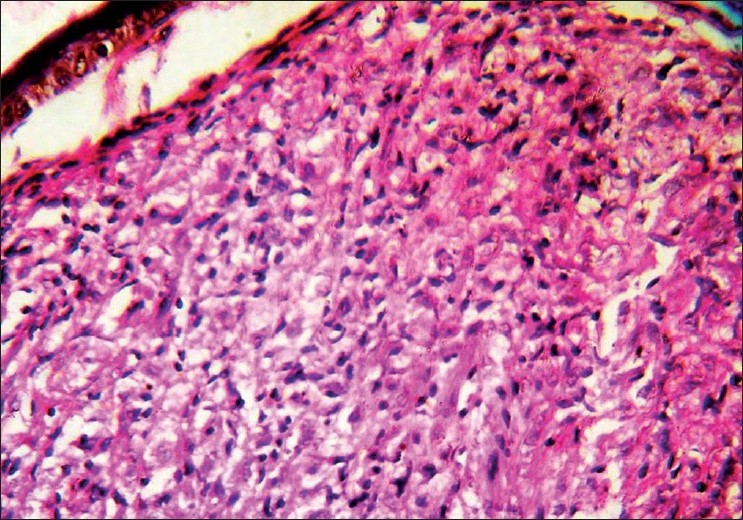

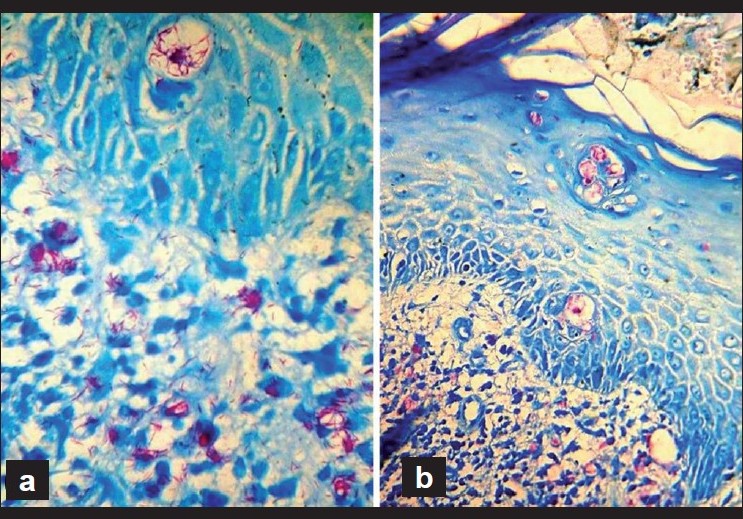

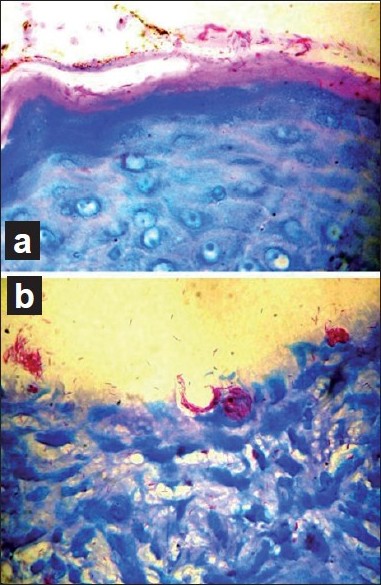

Histopathology from an intact nodule over left elbow at the initial presentation showed dermal granulomas of tightly packed spindle-shaped histiocytes in whorls and bundles with foamy macrophages and a Grenz zone [Figure - 2]. Ziehl-Neelsen stain revealed numerous solid staining acid fast bacilli arranged discretely and in clumps inside the dermis, including the Grenz zone, and surprisingly also inside the epidermis, in vacuoles in the prickle cell layer and in the stratum granulosum [Figure - 3]a and b, as well as being liberated from the eroded upper dermis (in biopsy from an abraded nodule) [Figure - 4]a and b. The presence of bacilli at various levels inside the epidermis suggested their movement upward along with the epidermal cells maturation and their ultimate elimination from the stratum corneum. This was not an artifact and the bacilli were not transferred from dermis to the keratinous layer by the knife, but were due to movement of bacilli upward from the basal layer and at various levels in malpigian layer. Slit smear examination from routine sites, including both ear lobes and four nodular lesions, was highly positive, with a bacterial index of 6+ (>1000 bacilli per oil immersion field and morphological index of 80%). Routine hematology, liver and kidney function tests were normal and blood venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for HIV 1 and 2 were negative. He was given daily rifampicin 600 mg and ofloxacin 400 mg for 2 months, followed by multi-bacillary (MB) Multi Drug Treatment (MDT) with daily dapsone 100 mg, clofazimine 300 mg monthly and 50 mg daily, and monthly rifampicin 600 mg for 2 years. Follow-up was done at monthly intervals for 3 years. There was marked regression of the skin lesions after 6 months and the bacterial and morphological index of the slit smear which was 6 + and 80% initially, rapidly reduced on repeat slit smears done after every 3 months, and after completion of 26 months of treatment, it was 1 + and 5%, respectively.

|

| Figure 2 :Dermal granulomas of closely packed spindle-shaped histiocytes in whorls with foamy macrophages and a Grenz zone (H and E, ×400) |

|

| Figure 3 :(a) Histopathology from an intact nodule near left elbow, showing numerous solid staining bacilli arranged discretely and in multiple globi in the upper dermis and inside a big vacuole in the prickle cell layer (Ziehl-Neelsen stain, ×1000); (b) similar solid staining bacilli seen inside vacuoles at various levels in the prickle cell layer and in the stratum granulosum (Ziehl-Neelsen stain, ×400) |

|

| Figure 4 :(a) Close-up view from an intact nodule showing numerous acid fast bacilli in the stratum corneum (Ziehl-Neelsen stain, ×1000); (b) close-up view of histopathology from an abraded nodule with numerous acid fast bacilli being liberated from the abraded upper dermis (Ziehl-Neelsen stain, ×1000) |

Discussion

Histoid leprosy presents with shiny, skin colored or erythematous papules, nodules or plaques arising abruptly over normal skin, mostly after inadequate or irregular treatment or because of dapsone resistant mutant strains, but may occur de novo. [1]

There are scant reports of detection of M. leprae inside the epidermis in leprosy, [2],[3],[4] and as opined, they could be missed/underreported, unless specifically looked for. [2] Okada et al. [4] suggested that dermal bacilli could be gradually transferred to the epidermal layers through phagocytic activity of young basal cells, and finally eliminated, possibly from the intact skin. Namisato et al. [5] described "transepidermal elimination" (TEE) of M. leprae in lepromatous leprosy and attributed it to rapidly growing dense granulomas in the upper dermis. The presence of bacilli in all layers of epidermis indicates that the bacilli which are taken up by the basal cells from the upper dermis can move upward with and inside the epidermal cells and are ultimately eliminated from the stratum corneum into the environment. The very large area of skin of about 1.62 m 2 in an adult Indian and the average turnover time of about 28 days seems to provide an opportune environment for bacillary multiplication and elimination, as even 1 g of lepromatous tissue is estimated to carry up to 7 billion bacilli. It is also known that the bacilli once eliminated could remain viable for several days or weeks. [6] As shown in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies, 60% of untreated MB patients had bacilli in the keratin layer, and 80% had M. leprae DNA in skin washings. [7]

Interestingly, on the other hand, the reports of initial/single leprosy lesions developing at the site of tattooing, vaccination scar or trauma suggest that the bacilli could gain entry through traumatized skin. The recent report of linearly distributed skin lesions suggesting pseudo-isomorphic phenomenon of Kobner in a histoid leprosy patient points toward cutaneous inoculation of the bacillus. [8] The addition of daily rifampicin and ofloxacin for 2 months before regular World Health Organization (WHO) MB MDT seems to have an advantage of making the patient non-infectious faster, as shown in this case and in a previous patient of histoid leprosy. [8]

Dendritic cells are antigen-presenting cells which phagocytose particles and microorganisms and are represented by Langerhans cells in the epidermis. They have a role in the cutaneous response to leprosy, which may be a determinant of the course and clinical expression of the disease. [9] Future studies on their contribution, if any, in the carriage and response to the presence of epidermal bacilli might help unravel a few unexplored aspects of leprosy.

The transepidermal exit of the M. leprae demonstrated in this case, along with previous reports mentioned above, indicate that possibly skin could be a portal of both exit and entry for the bacillus and should be given due recognition for its contributory role in leprosy transmission.

| 1. |

Sehgal VN, Aggarwal A, Srivastava G, Sharma N, Sharma S. Evolution of histoid leprosy (de novo) in lepromatous (multibacillary) leprosy. Int J Dermatol 2005;44:576-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Satapathy J, Kar BR, Job CK. Presence of Mycobacterium leprae in the epidermal cells of lepromatous skin and its significance. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2005;71:267-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Seo VH, Cho W, Choi HY, Hah YM, Cho SN. Mycobacterium leprae in the epidermis: Ultrastructural study I. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1995;63:101-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Okada S, Komura J, Nishiura M. Mycobacterium leprae found in epidermal cells by electron microscopy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Disth 1978;46:30-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Namisato M, Kakuta M, Kawatsu K, Obara A, Izumi S, Ogawa H. Transepidermal elimination of lepromatous granuloma: A mechanism for mass transport of viable bacilli. Lep Rev 1997;68:167-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Noordeen SK. The epidemiology of leprosy. In: Hastings RC, Opromolla DV, editors. Leprosy. 2 nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. p. 36-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Job CK, Jayakumar J, Kearney M, Gillis TP. Transmission of leprosy: A study of skin and nasal secretions of household contacts of leprosy patients using PCR. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008;78:518-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Ghorpade A. Molluscoid skin lesions in histoid leprosy with pseudo-isomorphic Koebner phenomenon. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:1278-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Simυes Quaresma JA, de Oliveira MF, Ribeiro Guimarγes AC, de Brito EB, de Brito RB, Pagliari C, et al. CD1a and factor XIIIa immunohistochemistry in leprosy: A possible role of dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of Mycobacterium leprae infection. Am J Dermatopathol 2009;31:527-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,004

PDF downloads

2,251