Translate this page into:

Treatment of stable and recalcitrant depigmented skin conditions by autologous punch grafting

Correspondence Address:

Koushik Lahiri

"Dakshinee" Frazer Avenue, Burdwan-713101

India

| How to cite this article: Lahiri K, Sengupta S R. Treatment of stable and recalcitrant depigmented skin conditions by autologous punch grafting. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1997;63:11-14 |

Abstract

Sixty cases of stable and refractory depigmented skin conditions which include local vitiligo, segmental vitiligo, chemical leucoderma, vitiligo vulgaris, post-burn depigmentation etc constitute the study group. 39 of them were female and 21 male. Age ranged between 6 and 67 years. 1057 grafts were placed over 114 lesions and the cases were followed up to a period of 18 months. 70% to 100% repigmentation was observed in 56 lesions of 31 patients. Rate and extent of perigraft pigment spread was noted. Patients under PUVASOL showed a distinctly better response. Sequelae like cobble-stoning and polka-dotting were found to be disappearing with time or interference.

Introduction

Skin grafting was first performed way back in 1804 by Baronio.[1] Lewin and Peck in 1941 recorded autograft response of dark-skinned autograft in spotted guinea pigs.[2] But in 1972 it was Orentriech et al who first introduced autograft repigmenstation of leucoderma.[3] Later on Falabella, Bonafe, Westerhof published many articles on this topic.[4][5][6][7][8][9] Of late surgical correction of vitiligo and other forms of cutaneous achromia spearheaded by punch grafting has become very popular in our subcontinent where the majority of the population belongs to darker skin types.

Materials and Methods

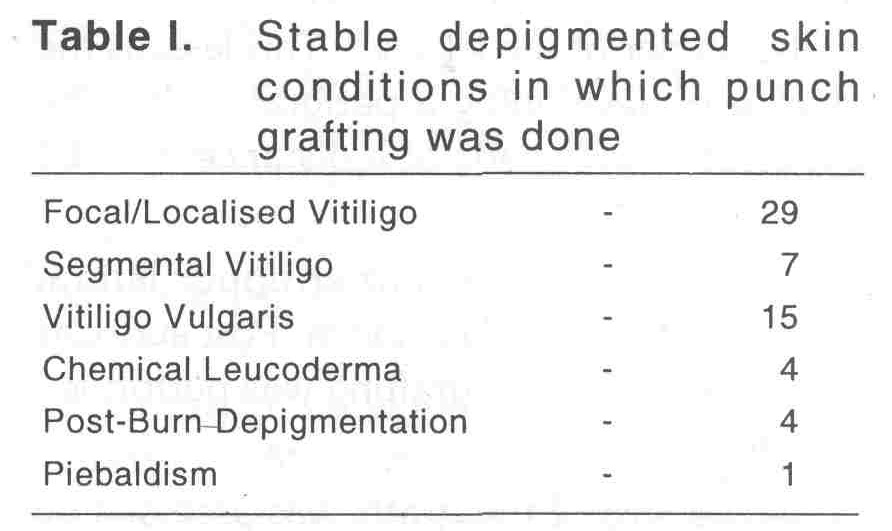

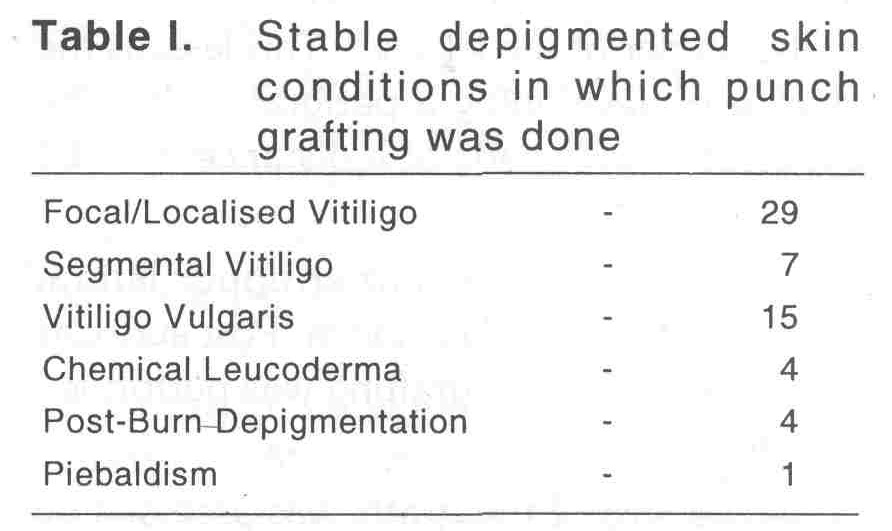

Sixty cases of stable depigmented skin conditions which encompass stable and recalcitrant lesions of focal vitiligo, segmental vitiligo, vitiligo vulgaris, chemical leucoderma, post-burn depigmentation and piebaldism constistute the sample population [Table - 1].

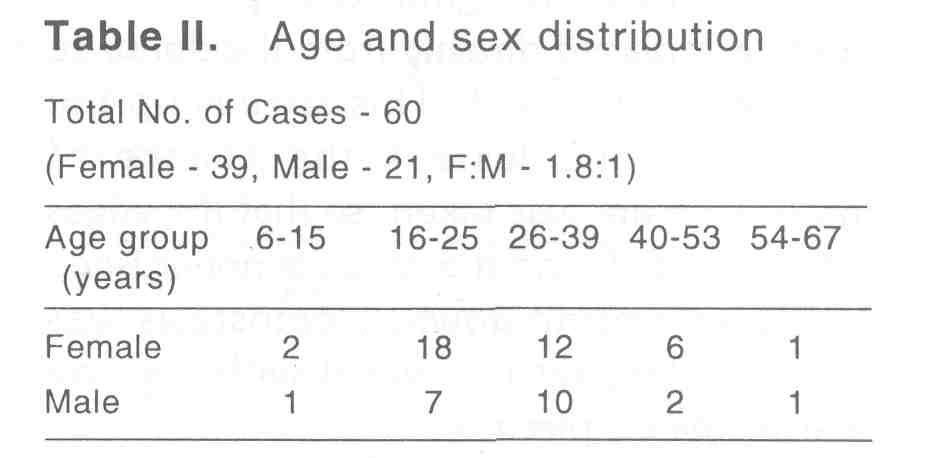

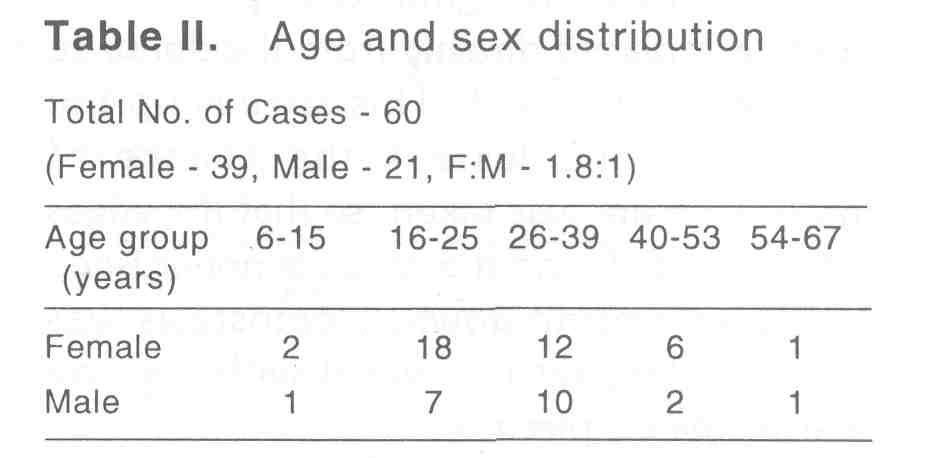

The study shows a definite female preponderence (F:M= 1.8:1). The age group of predilection in case of females was 16-25 years (46%) and in case of males 26-30 years (47%) [Table - 2].

In the present study the cases were stable for a period of 6 months to 17 years. Stability was adjudged from the history itself. The case which are stable for at least 6 months were taken up for the study. Koebner′s phenomenon also served as a simple yet important guide in assessing stability. In case of slightest doubt of unstability, minigraft test was performed.[8]

Old scars and BCG scars are examined to exclude the keloidal tendency. Routine blood examination including bleeding and clotting time and sugar estimations were done. Two doese of tetanus toxoid were given. The procedure and prognosis was explained to the patient. Prior consent and photography are necessary prerequisites.

Recipient area was prepared first. 2% lignocaine with or without adrenaline was infiltrated as local anasthetic. 2mm punches were used to prepare the recipient chambers. Initial chambers were made on or very close to the border of the lesion.[10] This lessens the chance of developing a perigraft halo. The chambers were made at a distance of 5-10mm from each other.

Donor area was either upper lateral portion of thigh or gluteal area. Post auricular area was used when grafting was performed over face.

The size of the grafts was assessed by placing one graft in a recipient hole to see whether it fits properly. After assessing the optimum size further grafts were placed. The grafts are placed directly from the donor to the recipient area.[10] This speeds up the procedure and lessens the chance of infection. Care was taken, so that the edges are not folded, and the tissue is not crushed or placed upside down. Hemostasis was achieved by presing over it with a saline soacked gauze piece.

Dressing was done with JELONET (paraffin soaked sterile dressing) over the recipient area and with OP-SITE over the donor area. JELONET is a non-adherent dressing while OP-SITE reduces the chance of post-op pain. Area is immobilised, if necessary. Routinely a course of antibiotic is given. Dressing was opened after 24 hours to see for any dislodgement of grafts, if found any, they were replaced. Finally after 5-7 days dressing was removed.

All the patients were given a daily dose of 0.6 mg/kg of 8-MOP after breakfast followed by exposure to sun after 2 hours for 15-30 minutes. The patients were followed up fortnightly for initial two months and then monthly upto a period of 18 months.

Results

A total of 1057 grafts were placed over 114 different sites in 60 subjects. The size of the lesion varied from 200mm2 to 14400mm2. Maximum perigraft pigment spread was 10mm noted over face and the minimum being 1mm noted over lower lumbar region. The mean area of repigmentation from one graft was 112mm2 (approx).

Earliest pigment spread was noted on the 14th day over face and the latest being over back of the thigh on 34th day (as reported by the patients).

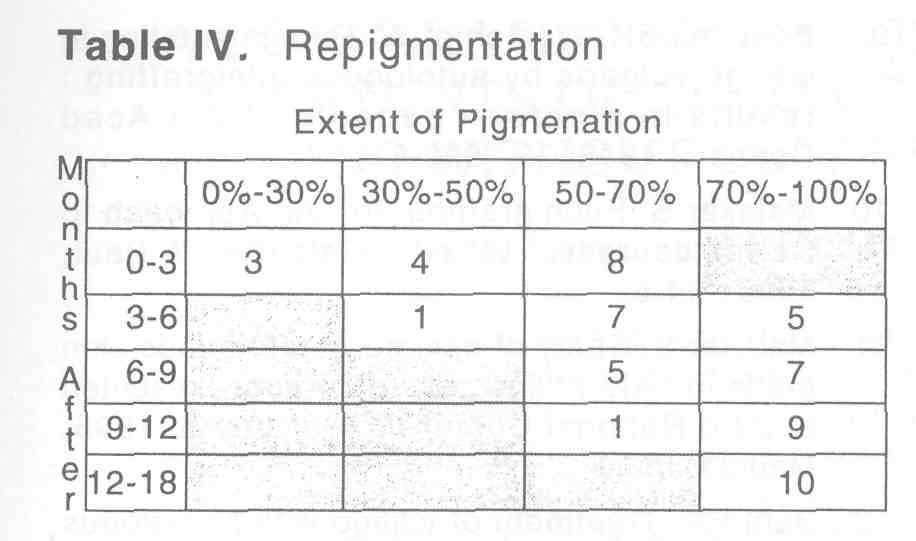

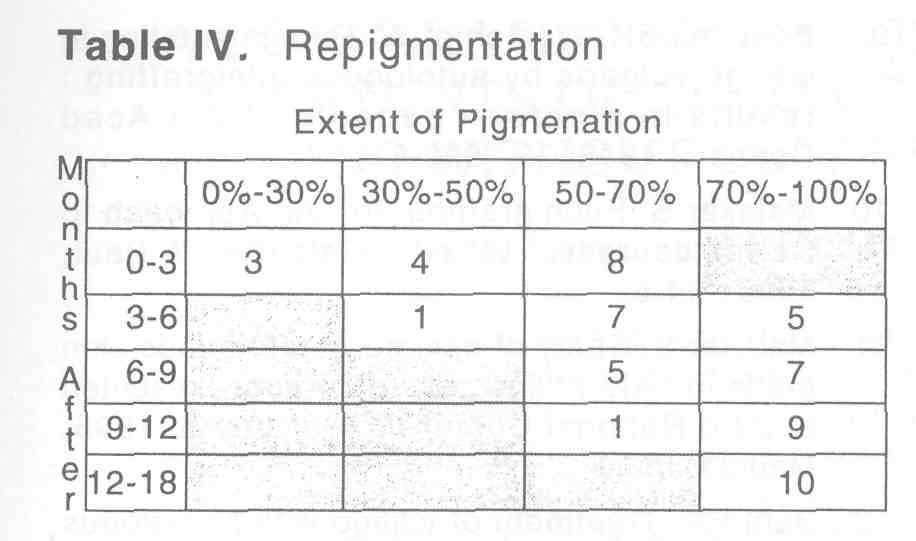

[Table - 4] shows the extent of pigment spread. 70% to 100% repigmentation was achieved in 31 patients (56 lesions), 50%-70% in 21 patients (39 lesions), 30%-50% in 5 patients (12 lesions) and 0%-30% in 3 patients (7 lesions).

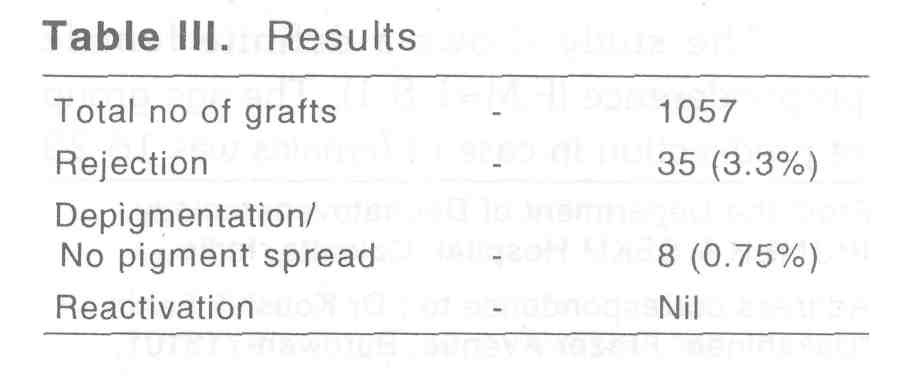

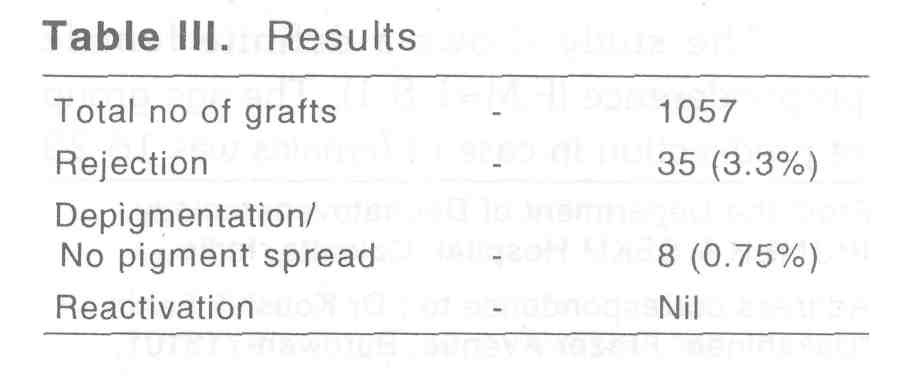

Rejection of grafts, depigmentation of grafts and keloidal tendency over the donor or recipient area were noted only in a few cases. But not a single case of vitiligo reactivation was observed in the present study [Table - 3].

Perigraft halo was noted in initial 7 patients. By placing the grafts properly at the borders in the later cases, this side effect was corrected.

Cases who could not tolerate oral psoralen or dicontinued PUVASOL on their own showed a poorer outcome in comparison to those who continued PUVASOL althrough.

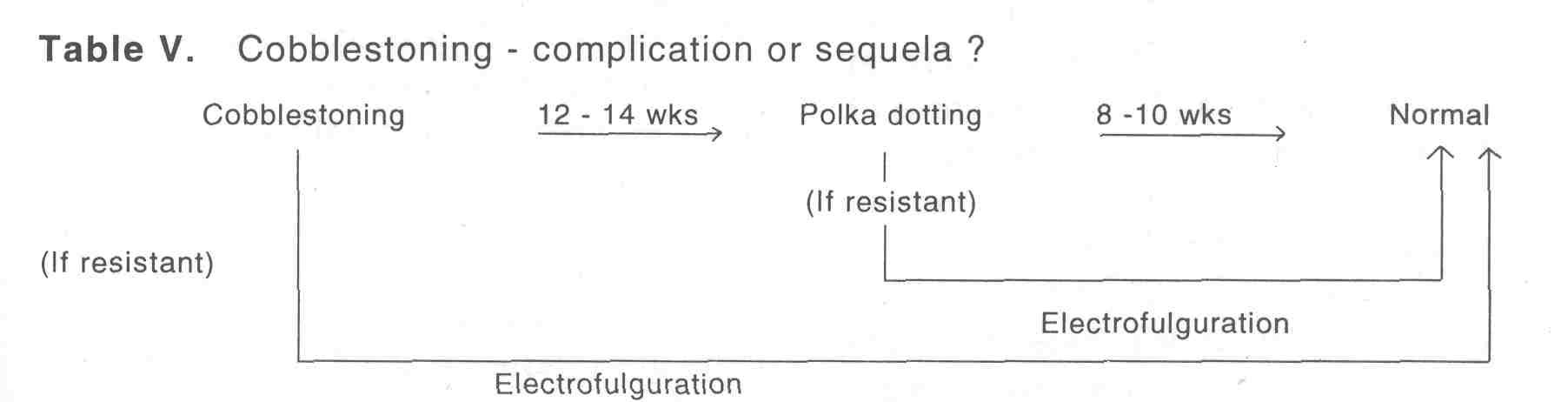

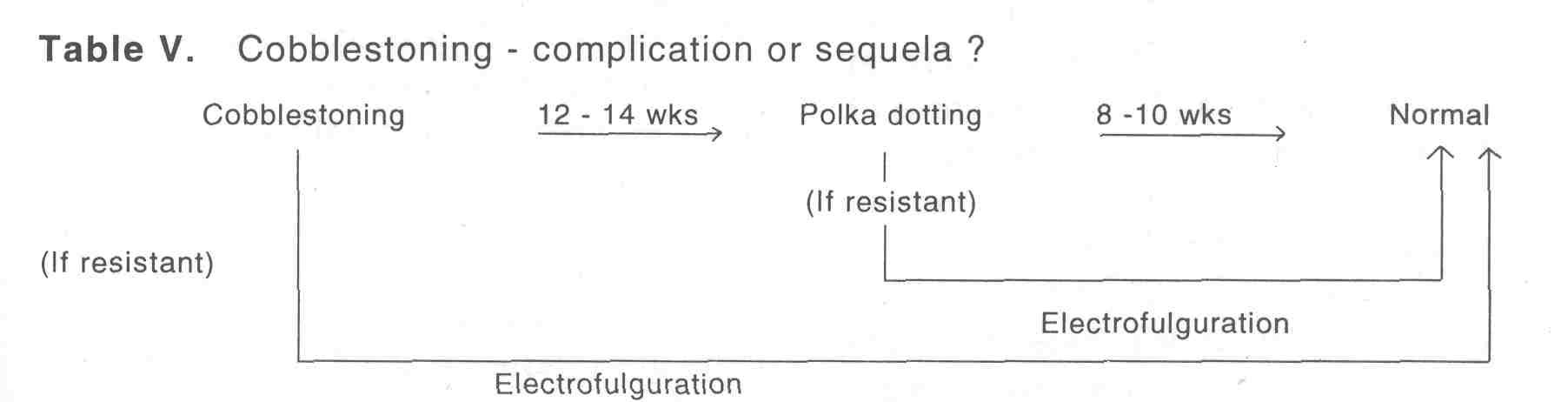

Cobblestoing was noted in 28 patients. In 23 of them it was found to be disappearing with time. In resistant 5 cases electrofulguration evoked very good response[11] [Table - 5].

Discussion

The original article of Orentriech et al[3] is regarded as an watershed line in the history of therapy of cutaueous achromia. He reported only 1mm to 2mm pigment from the grafts. Later on Westerhoff reported 5mm spread.[9] But in this part of the world where the majority to population belongs to the darker skin types ([Table - 3],[Table - 4],[Table - 5]) the extent of perigraft pigmentation is much larger than their western counterparts. Das and Pasricha even reported 18mm diameter of pigmentation from a single graft.[15] In our study we observed quite favourable perigraft pigmentation. The mean area of repigmentation from one graft is approximately 112mm2. Falabella reported success with punch grafting in segmental vitiligo, localised vitiligo, leucoderma and some other conditions. [4, 6, 8] Bonafe stressed the need of simultaneous PUVA therapy.[7] Boersma and Westerhof showed that this procedure can evoke encouraging results even in case of vitiligo vulgaris. But the assessment of stability is a must. Orentriech in his original article mentioned about some test grafts,[3] but Falabella formulated the minigrafting test to detect the stable lesions.[8] Behl published his pioneering work as early as in 1964 on thin Thierch grafts.[12] Of late many workers are working in this field in our country.[14][15][16][17] Malaker reported success with same sized grafts, directly placing them from the donor areas.[10] The role of electrofulguration is resistant cobblestonning and polka dotting was found to be very effective.[11]

Digital image analysis in measuring the perigraft pigment spread by Boersma and Westerhof is an important step forward in this field.[9] Prior computerised mapping of the depigmented area and assesment of the exact number of grafts may be incorporated to open new vistas in the field of surgical correction of cutaneous achromia.

| 1. |

Baronio G. Degli innesti animali, Milano, Stampperia e Fonderia del genio, 1804.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Lewin ML, Peck SM. Pigment studies in skin grafts on experimental animals. J Invest Dermatol 1941;4:504.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Orentriech N, Selmanwitz VJ. Autograft repigmentation of leucoderma. Arch Dermatol 1972;105:734-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Falabella R. Repigmenation of leucoderma by minigrafting of normal pigmented, autologous skin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1987;4:916-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Falabella R. Repigmentation of segmental vitiligo by autologus minigrafting. J Am Acad Dermatol 1983;9:514-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Falabella R. Treatment of localised vitiligo by autologus minigrafting. Arch Dermatol 1988;124:1649-55.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Bonafe LJ, et al. Pigmenation induced in vitiligo by normal skin grafts and PUVA stimulation : a preliminary study. Dermatologica 1983;166:113-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Falabella R, et al. The minigrafting test for vitiligo : dectection of stable lesions for melanocyte transplantion. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;32:228-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Boersma BR, Westerhof W. Repigmentation in vitiligo vulgaris by autologous minigrafting : results in nineteen patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33:990-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Malakar S. Puch grafting. In : An Approach to Dermatosurgery. 1st edn. Calcutta : A Paul, 1996:44-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Malakar S. Study of miniature autologous skin grafts in sixty vitiligo patients. Paper presented at 23rd National Conference of IADVL 1995, Madras, India.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Behl PN. Treatment of vitiligo with homologus thin Thiersch skin grafts. Curr Med Pract 1964;8:218-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Behl PN. Repigmentation of segmental vitiligo by autologus mingrating (letter). J Am Acad Dermatol Surg Oncol 1995;11:1218-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Sawant SS. Autologus miniature punch skin grafting in stable vitiligo. Ind J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1992;58:310-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Das SS, Pasricha JS. Punchgrafting as a treatment for residual lesions of vitiligo. Ind J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1992;58:315-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Jha AK, Pandey SS, Shukla VK. Punch grafting in vitiligo. Ind J Dermatol Venerol Leprol 1992;58:328-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Singh KG, Bajaj AK. Autologus miniature skin punch grafting in vitiligo. Ind J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1995;61:77-80.

[Google Scholar]

|