Translate this page into:

Validation and usability of modified palmoplantar psoriasis area and severity index in patients with palmoplantar psoriasis: A prospective longitudinal cohort study

Corresponding author: Prof. Sunil Dogra, Department of Dermatology Venereology and Leprology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education andResearch (PGIMER), Chandigarh, India. sundogra@hotmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Nagendran A, Hanumanthu V, Dogra S, Narang T, Pinnaka LVM. Validation and usability of modified palmoplantar psoriasis area and severity index in patients with palmoplantar psoriasis: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2024;90:275-82. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_712_2022

Abstract

Background

Palmoplantar psoriasis (PPP), a troublesome variant, does not have any validated scoring system to assess disease severity.

Objective

To validate modified Palmoplantar Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (m-PPPASI) in patients affected with PPP and to categorise it based on Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

Methods

In this prospective study, patients with PPP aged > 18 years visiting the psoriasis clinic at a tertiary care centre were included and requested to complete DLQI during each visit at baseline, 2nd week, 6th and 12th week. m-PPPASI was used by the raters to determine the disease severity.

Results

Overall, 73 patients were included. m-PPPASI demonstrated high internal consistency (α = 0.99), test-retest reliability of all three raters, that is, Adithya Nagendran (AN) (r = 0.99, p < 0.0001), Tarun Narang (TN) (r = 1.0, p < 0.0001) and Sunil Dogra (SD) (r = 1.0, p < 0.0001) and inter-rater agreement (intra-class correlation coefficient = 0.83). Face and content validity index for items I-CVI = 0.845 were robust, and the instrument was uniformly rated as easy to use (Likert scale 2) by all three raters. It was found to be responsive to change (r = 0.92, p < 0.0001). Minimal clinically important differences (MCID)-1 and MCID-2 calculated by receiver operating characteristic curve using DLQI as anchor were 2 and 35%, respectively. DLQI equivalent cutoff points for m-PPPASI were 0–5 for mild, 6–9 for moderate, 10–19 for severe, and 20–72 for very severe disease.

Limitation

Small sample size and single-center validation were the major limitations. m-PPPASI doesn’t objectively measure all characteristics of PPP such as “fissuring” and “scaling” which could also be taken into consideration.

Conclusion

m-PPPASI is validated in PPP and can be readily utilized by physicians. However, further large-scale studies are needed.

Keywords

Palmoplantar psoriasis

modified palmoplantar psoriasis area and severity index

Plain Language Summary

Palmoplantar psoriasis is a difficult to treat, but common subtype of psoriasis affecting the palms and soles. It may have a great impact on quality of life based on the disease severity. Till date, there is no validated scoring instrument to score its severity. Though modified palmoplantar pustular psoriasis area and severity index is the frequently used scoring system used to score the severity of PPP, it is not validated. We validated this scoring system, which may be used in clinical practice and in clinical trials.

Introduction

Around 2–3% of the world population suffers from the chronic skin condition psoriasis, which is inflammatory and also hyperproliferative.1 In India, the prevalence of psoriasis according to various studies has been proposed to be between 0.8 and 8%.2–5 It is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular comorbidities and renal complications.6–8 Psoriasis affecting the palms and soles is known as PPP, and it may occur with psoriasis elsewhere or maybe the only site involved. PPP can decrease a patient’s quality of life in comparison to moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis of the same magnitude.9,10 Various studies have reported that palmoplantar involvement was seen in 2.8–40.9% of psoriatic patients.11 In a study of 3065 patients with psoriasis, its prevalence was found to be 17.4%.12 This study was performed at a tertiary care center in North India. The cardinal symptoms of PPP are іtchіng, burning and painful fissures. Though palms and soles contribute a little share to the total body surface area, because of their cosmetic and occupational appeal, it can be singularly debilitating. Evidence-based practice has necessitated the evaluation of a patient with psoriasis based upon standard and necessary assessment of ailment severity including variables, that are quintessential to patients. In this light, using validated severity scores is important for both clinical practice and research. An important lacuna in studies on the treatment of PPP is the lack of a disease-specific validated severity score or index. In several studies, the PPP area and severity index (PPPASI) and its various modifications have been used to assess the disease severity and response to treatment but none of them was uniform and validated.11,13–17 Thus, we conducted this study to validate the modified palmoplantar psoriasis area and severity index (m-PPPASI).

Materials and methods

This was a prospective cohort study conducted in the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh, India) from July 2016 to December 2017, after obtaining the Institutional Ethical Committee clearance. A total of 73 patients with PPP satisfying inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited after obtaining written informed consent.

Diagnosis of PPP and selection criteria

PPP was diagnosed based on clinical details and examination. Histopathology was done only in cases of doubtful diagnosis. The PPP with pustulation overlying the infiltrated plaques was treated as plaque-type PPP. The m-PPPASI, a novel scoring system which slightly differs from the original PPPASI, is used to assess the severity and area of psoriatic involvement for each clinical sign such as erythema, infiltration (for plaque PPP) or pustules (for pustular PPP) and desquamation of palms and soles [Table 1].14 Patients with PPP who were >18 years of age with a duration of disease >6 months and literate enough to fill the DLQI forms were included in the study. Patients having psoriatic arthritis; systemic comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, cardiac and renal disease; having lesions of psoriasis affecting areas other than palms and soles; pregnant and lactating women and those already on systemic treatment for severe PPP were excluded from the study.

Skin sign

Right palm

Left palm

Right sole

Left sole

Erythema

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Infiltration (plaque PPP) or Pustules (pustular PPP)

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Desquamation

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Score from 0 to 4

Total clinical severity

Max: 12

Max: 12

Max: 12

Max: 12

Extent of involvement

0 = none, <10% = 1, 10–29% = 2, 30–49% = 3, 50–69% = 4, 70–89% = 5 and 90–100% = 6

Total extent of involvement

Max = 6 × 0.2

Max = 6 × 0.2

Max = 6 × 0.3

Max = 6 × 0.3

Multiply total extent of involvement and total clinical severity

A (Max = 14.4)

B (Max = 14.4)

C (Max = 21.6)

D (Max = 21.6)

Total score

A + B + C + D = 72 (Maximum)

Patient assessment

Clinical examination including m-PPPASI for palms and soles was documented in a predesigned case record form. Additionally, DLQI which is an accepted indicator of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) specific to dermatologic patients, was validated in english and translated to Hindi, and Punjabi languages for patient comprehension. DLQI questionnaire was provided to the patients and was followed up on 2nd, 6th and 12th week. All the recruited patients were treated based on DLQI scores, since there is no validated score in guiding the treatment in PPP (PPP with DLQI scores ranging between 11 and 20 and 21 and 30 was considered as severe and very severe/disabling, respectively, and treated with systemic agents along with topical medications, while DLQI score between 1 and 10 was considered as mild to moderate disease and treated with topical medications only).18 To evaluate the m-PPPASI test-retest reliability, the investigators administered the index to the patient at baseline and after a 2 week period in which the patient was advised to use topical emollients that would have a negligible effect on disease severity. At the time of presentation, all patients with PPP who fulfilled the above criteria were evaluated and scored by three sperate physicians (Adithya Nagendran, Tarun Narang and Sunil Dogra) in the clinic. Digital photographs were also taken at baseline, 2, 6 and 12 weeks. The taxonomy and definitions of the measurement properties utilised in this study are based on the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments study.19

Outcome parameters and statistical analysis

The data obtained from m-PPPASI was quantitative and were analyzed utilizing the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS version 22.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States). For all the statistical tests mentioned below, DLQI was utilised as the gold standard for comparison with m-PPPASI.

For inter-rater agreement, all the patients were independently scored by each physician without knowing the other’s score. Inter-rater agreement is defined as the degree to which two different or more observers acquire an equivalent result independently. Since the patient’s medical treatment did not change between the assessments, the likelihood of significant change in the patient’s clinical condition was reduced. The severity index did not interfere with the patients’ treatment decision and routine care.

We employed an accurate estimation of the surface area involved by the disease by defining the centre of the palm as 50% surface area of the hand, within which thenar and hypothenar eminence contribute 10 and 20%, respectively and each finger was taken as 10% of the surface area of the palm, to achieve a high degree of internal consistency by Cronbach’s α, inter-rater agreement by the intra-class correlation coefficient, and test-retest reliability by Pearson’s r.20 The sole barring the digits was taken as representing 80% of the surface area within which the instep was 20% and each of the digits was 4% surface of the foot. These deductions were considered logical and not entirely inaccurate by the investigators to apply in measuring palmoplantar surface area.

Face validity pertains to the extent to which a test or asessment appear to measure the intended concept, while content validity refers to the correlation between the test items and the symptom content of a clinical condition, which is what the m-PPPASI index superficially seems to measure. Around 20 untrained physicians were requested to rate the m-PPPASI index’s face validity and content validity. On a 5-point Likert-like scale, raters were asked to rate m-PPPASI’s ease of scoring in order to evaluate its usability. Seven experts were invited to utilise the content validity index for items to evaluate if all pertinent PPP elements were included in the m-PPPASI and whether any irrelevant ones were there.21 They were blinded to each other’s evaluation and the amount of time it took to complete the score was also noted. To evaluate the m-PPPASI responsiveness to change, we compared the scores of the m-PPPASI and DLQI scored by one rater at 2nd week and 6th week (using Pearson’s r). To evaluate the m-PPPASI interpretability, it was correlated with DLQI. For this purpose, MCID-1 and MCID-2 were defined as the smallest mean change and the smallest percentage reduction which may be used to identify responders to treatment, respectively. The MCID for DLQI was taken as 4 as recommended for inflammatory conditions.22 (Interpretability was computed by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis using DLQI as the anchor)

To categorise PPP based on m-PPPASI, it was correlated with DLQI and analysed by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Patients were classified into three bands “mild to moderate PPP”, “severe PPP” and “very severe/disabling PPP” based on the DLQI scores “0–5”, “6–10”, “11–20” and “21–30”, respectively which is consistent with the original five bands of DLQI scoring.18 The m-PPPASI score and DLQI scores were all quantitative data and we assumed that the m-PPPASI score and DLQI score followed a normal distribution.

Results

The distribution of cases and baseline demographic data are summarised in Table 2.

Study participant characteristics

Values

Distribution of cases (Frequency in %)

Palmar

14 (19.8%)

Plantar

6 (8.2%)

Palmoplantar

53 (72.6%)

Gender (Frequency in %)

Male

38 (53.4%)

Female

35 (46.6%)

Duration of illness in months (mean ± standard deviation)

10.0 ± 12.0

Age in years (mean ± standard deviation)

40.5 ± 13.5

The m-PPPASI score was validated in 73 patients with PPP and was assessed at baseline, 2 weeks, and 6 weeks, but only 58 patients could be assessed at 12 weeks, and the remaining 15 patients were lost to follow-up.

Internal consistency

All raters measured internal consistency for a total of 12 items at each interval of time (0, 2, 6 and 12 weeks) and the result was 0.99, indicating high internal consistency (α values above 0.8 are deemed to be appropriate).23

Test-retest reliability

Test-retest reliability of the individual raters tested by Pearson’s r showed a good correlation of all three raters Adithya Nagendran (AN) (r = 0.99, p < 0.0001), Tarun Narang (TN) (r = 1.0, p < 0.0001) and Sunil Dogra (SD) (r = 1.0, p < 0.0001).

Inter-rater agreement

The three raters’ inter-rater agreement, as determined by the intra-class correlation coefficient, was likewise shown to be significantly associated at four intervals of time (0, 2, 6 and 12 weeks), (intra-class correlation coefficient = 0.83, p < 0.0001) [Table 3]. Two-way mixed effects model where people effects are random and measures effects are fixed, a: The estimator is the same, whether the interaction effect is present or not, b: type A intra-class correlation coefficients using an absolute agreement definition, c: this estimate is computed assuming the interaction effect is absent, because it is not estimable otherwise

Intra-class correlation coefficient

Intra-class correlationb

95% confidence interval

F test with true value 0

Lower bound

Upper bound

Value

df1

df2

Significance

Single Measures

0.833a

0.749

0.893

100.530

57

627

0.000

Average measures

0.984c

0.973

0.990

100.530

57

627

0.000

Face validity and content validity

Around 20 untrained physicians provided their opinion in response to a questionnaire about whether the m-PPPASI instrument could be used to assess PPP on an ordinal dichotomous scale. They all concurred that PPP could be measured using the items that were mentioned. The content validity index for items was designed as a 4-point ordinal scale for the purpose of measuring the items quantitatively. This content validity index for items was further completed by seven experts and the m-PPPASI instrument’s overall mean content validity index for items was 0.845 [Table 4].

Question

“Not relevant” ratings

“Relevant” ratings

Item Content Validity Index (I-CVI)

Is erythema relevant in the measurement of palmoplantar psoriasis

0

7

1

Is infiltration relevant in the measurement of palmoplantar psoriasis (plaque PPP)

0

7

1

Is pustulation relevant in the measurement of palmoplantar psoriasis (pustule PPP)

1

6

0.9

Is desquamation relevant in the measurement of palmoplantar psoriasis

2

5

0.7

Does erythema, infiltration (plaque PPP), pustulation (pustule PPP) and desquamation taken together comprehensively reflect measurement of palmoplantar psoriasis?

2

5

0.7

Is erythema relevant for the purpose of application of the m-PPPASI instrument? (in evaluation)

2

5

0.7

Is infiltration relevant for the purpose of application of the m-PPPASI instrument? (in evaluation)

0

7

1

Is pustulation relevant for the purpose of application of the m-PPPASI instrument? (in evaluation)

1

6

0.9

Is desquamation relevant for the purpose of application of the m-PPPASI instrument? (in evaluation)

2

5

0.7

Is erythema relevant in the evaluation of palmoplantar psoriasis in the study population?

1

6

0.9

Is infiltration relevant in the evaluation of palmoplantar psoriasis in the study population?

0

7

1

Is pustulation relevant in the evaluation of palmoplantar psoriasis in the study population?

1

6

0.9

Is desquamation relevant in the evaluation of palmoplantar psoriasis in the study population?

2

5

0.7

Usability

The three raters used a 5-point Likert-like scale to determine how easy it was to score the m-PPPASI for each recording, and they all agreed that it was “easy to score” (rating of 2) [Table 5].

1st rater (Adithya Nagendran)

2nd rater (Tarun Narang)

3rd rater (Sunil Dogra)

0

2

6

12

0

2

6

12

0

2

6

12

week

week

week

week

week

week

week

week

week

week

week

week

Time taken in seconds

75.4

72.3

65.4

64.8

71.7

68.6

61.6

59.6

68.2

65.2

58.6

57.3

±

±

±

±

±

±

±

±

±

±

±

±

(Mean ± standard deviation)

22.7

21

20.6

21.3

21.7

21.5

21.8

21

21.7

22.3

20.2

19.2

Responsiveness to change and interpretability

Only the paired observations of the rater AN (m-PPPASI at 2 and 6 weeks) were used for analysing responsiveness to change, to prevent biases incurred from multiple observations on the same subjects. Pearson correlation of the m-PPASI score at 2 and 6 weeks was r = 0.92 (p < 0.0001) (n = 73). Similarly, for DLQI score, the Pearson’s correlation at 2 and 6 weeks was r = 0.7 (p < 0.0001) (n = 73). Since the correlations were >0.6 for both DLQI and m-PPPASI, they were considered to be suitable for MCID analysis.

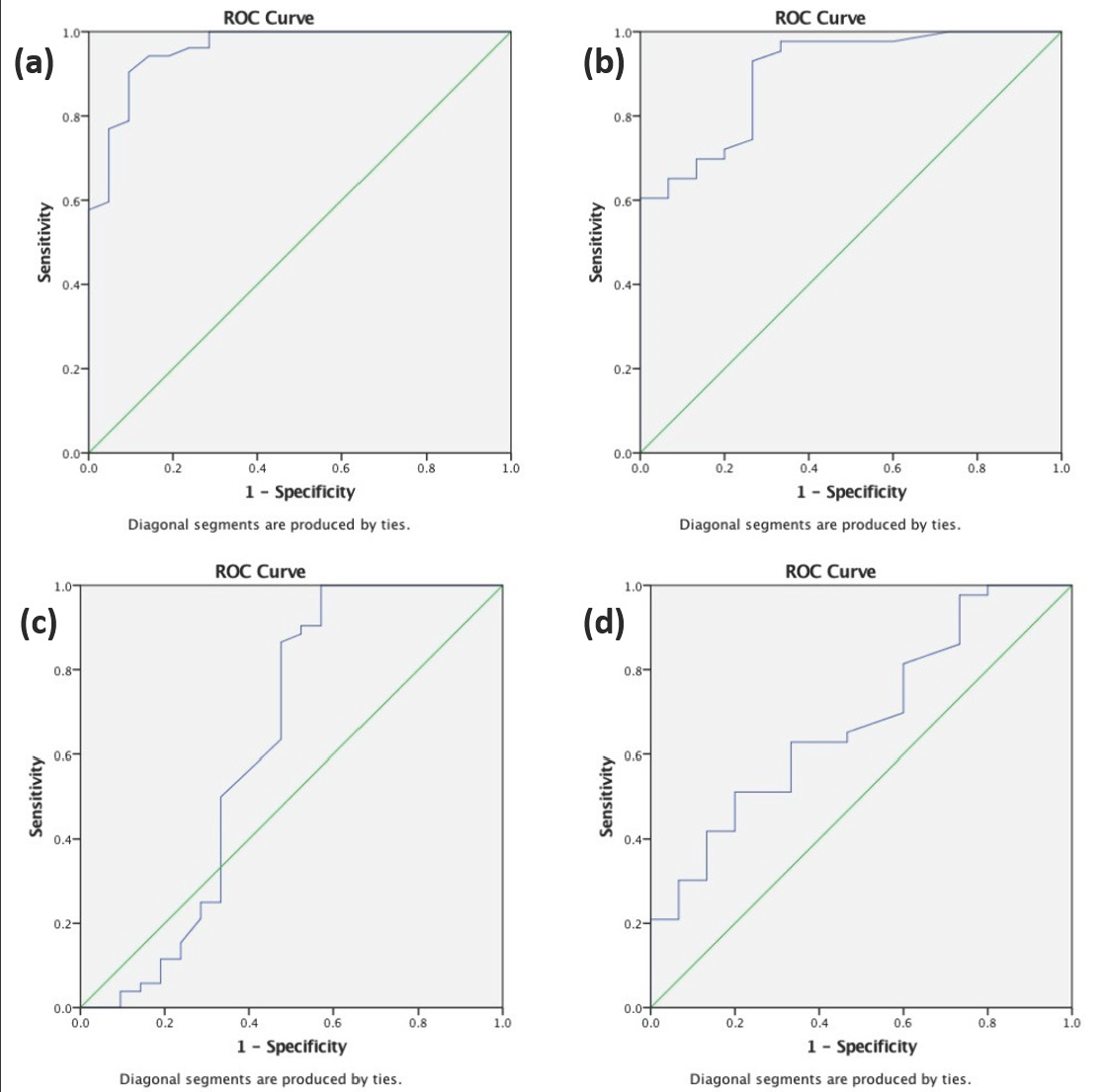

To measure interpretability, the smallest mean change (MCID-1) and smallest percentage reduction (MCID-2) in the m-PPASI score which could be clinically useful was calculated using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis from the data of one of the raters (AN) [Figure 1 and Table 6].

MCID: minimal clinically important differences, m-PPPASI: modified palmoplantar psorіasis area and severіty index, AUC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

Receiver operating characteristic curves for MCID-1 and MCID-2. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to calculate MCID-1 (a) Correlation is between point reduction of m-PPPASI at 0–6 weeks using point reduction of DLQI as an anchor at 0–6 weeks (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.95) (b) Correlation is between point reduction of m-PPPASI at 0–12 weeks using point reduction of DLQI as an anchor at 0–12 weeks (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.90) and MCID-2 (c) Correlation is between percentage reduction of m-PPPASI at 0–6 weeks using percentage reduction of DLQI at 0–6 weeks as an anchor (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.62) (d) Correlation is between percentage reduction of m-PPPASI at 0–12 weeks using percentage reduction of DLQI at 0–12 weeks as an anchor (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.68)

MCID-1

Change in score

Sensitivity

Specificity

AUC

m-PPPASI 0–6 weeks (n = 52)

1.3

0.96

0.76

0.95 (0.91–1.00)

1.4

0.94

0.81

1.5

0.94

0.85

m-PPPASI 0–12 weeks (n = 43)

2.2

0.95

0.66

0.90 (0.81–0.98)

2.4

0.93

0.73

2.5

0.90

0.73

MCID-2

m-PPPASI 0–6 weeks (n = 52)

32.5

0.65

0.52

0.62 (0.44–0.80)

33.1

0.63

0.52

33.5

0.50

0.67

m-PPPASI 0–12 weeks (n = 43)

39.8

0.69

0.40

0.68 (0.52–0.83)

40.5

0.65

0.53

41.9

0.62

0.53

The MCID-1 values obtained for m-PPPASI based on receiver operating characteristic curve analysis using DLQI as the anchor was 1.55 (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, [AUC] = 0.959) at week 6 and 2.40 at week 12 (AUC = 0.902), we, therefore, recommend that the integer 2 be used to define MCID-1 for m-PPPASI [Figures 1a and 1b]. Similarly, 33.1% (AUC = 0.625) reduction at 6 weeks and 40.5% (AUC = 0.681) reduction at 12 weeks, respectively defined MCID-2 for m-PPPASI, and for practical purposes we recommend a 35% reduction be defined as MCID-2 for m-PPPASI [Figures 1c and 1d].

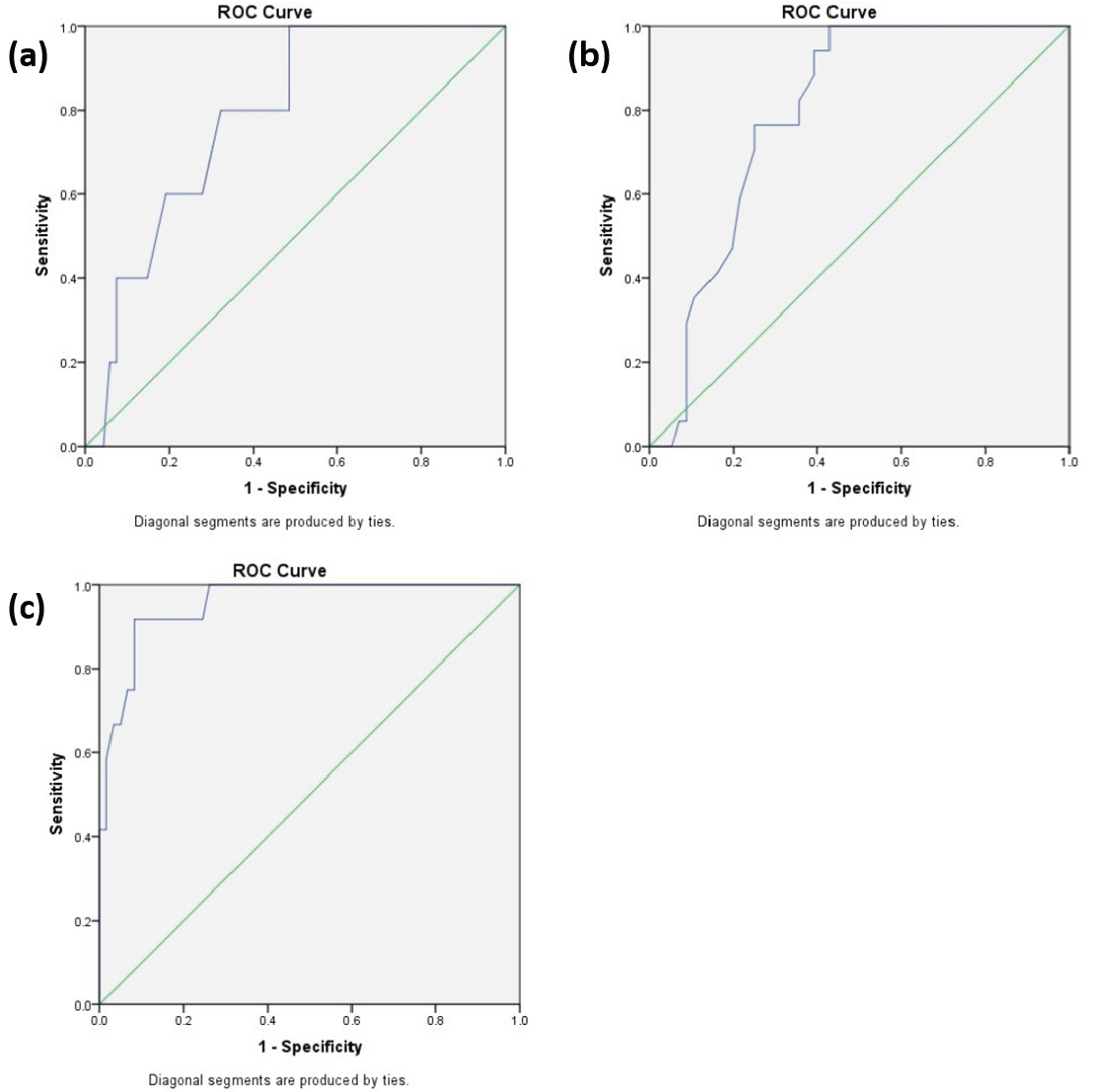

Categorisation

Using DLQI-based banding of the skin disease as a standard; we endeavoured to find the DLQI equivalent cutoff points for m-PPASI by using the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. The resulting m-PPPASI equivalents came to be <6.3 for mild PPP, <8.3 for moderate PPP and >18.5 for very severe PPP. Using these values, we propose the practical scores of 0–5, 6–9, 10–19 and 20–72 to be used for categorising mild, moderate, severe and very severe PPP, respectively. [Figure 2 and Table 7].

DLQI: dermatology life quality index, m-PPPASI, modified Palmoplantar Psorіasis Area and Severіty Index, AUC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

Receiver operating characteristic curves for categorisation. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to calculate cut-off points for m-PPPASI using (a) Using DLQI < 6 as an anchor point (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.78) (b) DLQI < 11 as an anchor point (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.79) (c) Using DLQI > 20 as an anchor point (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.95)

DLQI < 6

DLQI < 11

DLQI > 20

Mild PPP

Moderate PPP

Very severe PPP

m-PPPASI

Sensitivity (%)

Specificity (%)

Sensitivity (%)

Specificity (%)

Sensitivity (%)

Specificity (%)

5.7

60

72

6.3

80

68

6.7

80

66

8.0

77

64

8.3

82

64

8.7

88

61

18.0

92

90

18.5

92

92

18.75

83

92

AUC

0.78 (0.62–0.94)

0.79 (0.69–0.89)

0.95 (0.9–1.0)

Discussion

Due to the absence of a validated scoring system in PPP, many alternate methods have been utilised to score the disease severity in various studies done in the past which include assessment through the use of a series of photographs, physician’s global assessment, patient’s global assessment, etc. The fact that none of these methods have been validated or standardised for PPP is a major drawback. As a result, it is becoming challenging to directly compare the studies. In this study, we tried to validate m- PPPASI, so that a uniform and standardised measure could be made available that could be used across studies, and a comparison between them would be possible.

The good internal consistency of the m-PPPASI indicates that the items are well related to one another. It simply states that different observers may employ m-PPPASI at various times and it can be relied upon to make treatment decisions. Inter-rater agreement was also good between the three raters. The test-retest reliability of the measurement results at two distinct but near points in time by all three raters shows that m-PPPASI demonstrates minimal fluctuation with the same observer when the disease remains static.

According to the literature, an item is considered to have passed the test of content validity if its content validity index for items is more than 0.78; nevertheless, several of the items failed this test.21 As in, the term “desquamation” ws deemed inappropriate for measuring the intended purpose of m-PPPASI, leading to the conclusion that the m-PPPASI was not appropriate for the study population. This was because experts believed that vesicular lesions, rather than psoriatic plaques, typically desquamate during healing. Instead, they suggested using the term “scaling,” which was more appropriate for plaques. “erythema”, “infiltration” (plaque PPP), “pustulation” (pustule PPP), and “desquamation” taken together were also not found to comprehensively reflect the measurement of PPP as it was felt that the other features to consider would be “fissuring” and “scaling” to objectively measure PPP. Due to inadequate sample size for the calculation, construct validity could not be tested, and criterion validity could not be performed due to the lack of a suitable “gold standard” to correlate the instrument with. DLQI being a quality of life instrument was deemed inappropriate to correlate with. Neverthless, we could establish a positive correlation between the DLQI and the m-PPPASI on several fronts, where it was considered appropriate. This was partly due to the absence of other standardized and validated instruments. An instrument aiming to clinically measure the disease would find little to no utility if it cannot reflect the change in status of the disease it purports to measure. Hence, in studying the responsiveness to change of the m-PPPASI, we correlated it with DLQI and found that m-PPPASI varied in parallel with the DLQI. This suggests that the m-PPPASI is at least as robust as the DLQI in monitoring responsiveness. We found that a decrease or increase in the value of m-PPPASI by at least 2 (defined by MCID-1) would suggest to the physician an alteration in the disease characteristic. Similarly, the smallest percentage reduction or increment that this value 2 would represent was calculated to be 35%, which means that there should be at least a 35% change in the disease for the physician to feel a treatment response (defined by MCID-2). For this purpose, we took a predefined smallest mean change in DLQI of 4 to be a measure of correlation with m-PPPASI. To increase the accuracy of MCID estimation, the receiver operating characteristic approach was used to determine MCID-1 and MCID-2, in which DLQI was used as an anchor. Since it has been argued that anchor-based methods to determine MCID are more clinically relevant than distribution-based studies. However, we recognised that responsiveness and MCID may differ depending on the population and the context; consequently, a single MCID may not be adequate or applicable to all study populations. Therefore, multiple clinically relevant anchors are considered for confirming responsiveness and determining MCID.24,25 We were only able to use DLQI as an anchor in our study because we were constrained by the absence of other relevant anchors which could be used in PPP; consequently, we anticipate that the MCIDs we have established will facilitate comparison in future m-PPPASI-based studies. Nevertheless, in order to support our conclusions, further investigations using other anchors, such as Psoriasis Global Assessment and Lattice-system Psoriasis Global Assessment, ought to be carried out.

An attempt at categorising m-PPPASI in a fashion similar to the DLQI banding was undertaken in this study and we propose that m-PPPASI scores of 0–5, 6–9, 10–19 and 20–72 be taken for grading PPP as mild, moderate, severe, and very severe, respectively. This is analogous to and is derived while correlating m-PPPASI with the DLQI banding of 0–5, 6–10, 11–20 and 21–30 as none to mild, mild to moderate, severe, and very severe or disabling, respectively.

We recommend this categorisation in a clinically controlled environment as a rough guide and not an exact grading system in actual clinical practice on which treatment decisions are based, for which, a case-to-case variation, tailoring, and the physician’s own experience may be more appropriate in guiding treatment decisions.

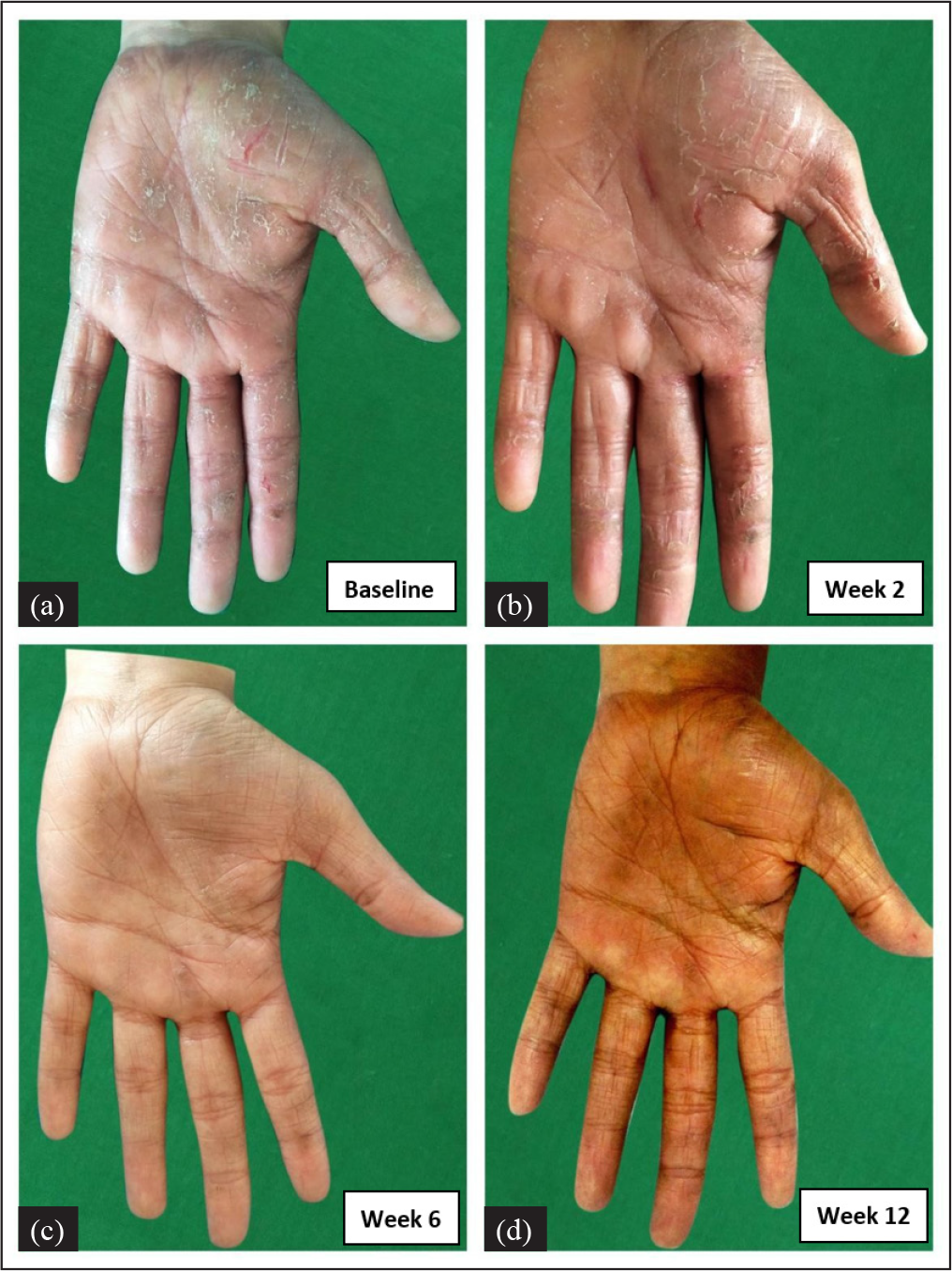

In Figure 3, the scoring of m-PPPASI in one patient with palmar psoriasis is illustrated as done by the three raters (AN, TN and Sunil Dogra (SD)).

- Palmar psoriasis. m-PPPASI as calculated by the 3 raters in this patient’s left palm was as follows: AN = 11.4, 11.4, 3 and 0.6, TN = 11.4, 11.4, 2.7 and 0.7 and Sunil Dogra (SD) = 11.4, 11.4, 3 and 0.6 at weeks 0 (a), 2 (b), 6 (c) and 12 (d) respectively

Limitations

Small sample size and single-centre validation were the major limitations. Palmoplantar pustulosis cases were not included, however, it is increasingly becoming clear that PPP and palmoplantar pustulosis maybe two different disease entities26 and it may not be appropriate to use a single scoring system to score both these entities. m-PPPASI doesn’t objectively measure all characteristics of PPP such as “fissuring” and “scaling” which could also be taken into consideration.

Conclusion

This is the first pilot study done for validation of m-PPPASI in the form of establishing reliability, good inter-rater agreement, face and content validity. The index was also found to be responsive to change, easily interpretable, and categorisable. Hence, we propose that the severity of the disease can be uniformly measured with m-PPPASI in both day-to-day clinical practice and clinical trials. This study will help in further research into PPP, which has traditionally been difficult to deal within psoriasis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Randomized clinical trials for psoriasis 1977–2000: The EDEN survey. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:738-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical profile of psoriasis in North India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:202-5.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natural history of psoriasis: A study from the Indian subcontinent. J Dermatol. 1997;24:230-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological pattern of psoriasis, vitiligo and atopic dermatitis in India: Hospital-based point prevalence. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S6-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Psoriasis in the tropics: An epidemiological survey. J Indian Med Assoc. 1963;41:550-6.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: A population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1173-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of incident chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in patients with psoriasis: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;78:232-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:84-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psoriasis in India: Prevalence and pattern. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:595-601.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmoplantar psoriasis is associated with greater impairment of health-related quality of life compared with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:623-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of systemic methotrexate vs. acitretin in psoriasis patients with significant palmoplantar involvement: A prospective, randomized study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e384-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmoplantar lesions in psoriasis: A study of 3065 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:192-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral liarozole in the treatment of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:546-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efalizumab for severe palmo-plantar psoriasis: An open-label pilot trial in five patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:415-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iontophoretic delivery of methotrexate in the treatment of palmar psoriasis: A randomised controlled study. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:140-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of oral methotrexate (MTX) monotherapy vs oral MTX plus narrowband ultraviolet light B phototherapy in palmoplantar psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13486.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the efficacy and safety of apremilast and methotrexate in patients with palmoplantar psoriasis: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:415-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:659-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The surface area of the hand and the palm for estimating percentage of total body surface area: Results of a meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:76-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:489-97.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the dermatology life quality index (DLQI): Further data. Dermatology. 2015;230:27-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development, test-retest reliability and validity of the pharmacy value-added services questionnaire (PVASQ) Pharm Pract (Granada). 2015;13:598.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Responsiveness to change and interpretability of the simplified psoriasis index. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:351-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:102-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1792-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]