Translate this page into:

Validation of the diagnostic criteria for segmental vitiligo

2 Department of Dermatology and STD, Safdurjung Hospital, New Delhi, India

3 Consultant Dermatologist, Pitampura, New Delhi, India

4 Consultant Dermatologist, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

5 Department of Biostatistics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Binod K Khaitan

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi

India

| How to cite this article: Gupta P, Khaitan BK, Ramam M, Ramesh V, Sundharam J A, Malhotra A, Gupta V, Sreenivas V. Validation of the diagnostic criteria for segmental vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2020;86:656-662 |

Abstract

Background: Segmental vitiligo has a different clinical course and prognosis as compared to nonsegmental vitiligo, which necessitates its correct diagnosis. It may be difficult to distinguish segmental vitiligo from the limited or focal types of nonsegmental vitiligo.

Objective: To validate the previously proposed diagnostic criteria for segmental vitiligo.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional validation study involving patients with limited vitiligo. The diagnostic criteria were used to classify vitiligo lesions as segmental or nonsegmental, and was compared with the experts' diagnosis, which was considered as the “gold standard”.

Results: The study included 200 patients with 225 vitiligo lesions. As per the diagnostic criteria, 146 vitiligo lesions were classified as segmental and 79 as nonsegmental. The experts classified 147 vitiligo lesions as segmental and 39 as nonsegmental, while the diagnosis either was labeled “unsure” or could not be agreed upon for 39 lesions. As compared with the experts' opinions (“for sure” cases, n = 186), the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic criteria was 91.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 86.2%–95.7%) and 100% (95% CI: 91%–100%), respectively. The positive predictive value was 100% (95% CI: 97.3–100%), while the negative predictive value was 76.5% (95% CI: 62.5%–87.2%). There was a 93.5% agreement between the clinical criteria and experts' opinions (k = 0.83, P < 0.001).

Limitation: The diagnostic criteria were compared with the experts' opinion in the absence of an established diagnostic “gold standard”.

Conclusions: The proposed diagnostic criteria for segmental vitiligo performed well, and can be used in clinical practice, as well as in research settings.

Introduction

Vitiligo can be broadly divided into two groups—segmental and nonsegmental. In contrast to nonsegmental vitiligo, segmental vitiligo usually has an early onset in childhood and is not associated with autoimmune diseases. In addition, in segmental vitiligo, the lesions usually evolve rapidly over a short span of time in a localized area and then remain stable, whereas nonsegmental vitiligo has a highly variable course with periods of progression, remission, stability and/or exacerbation.[1],[2] Due to significant differences in several aspects between these two types of vitiligo, early recognition of segmental vitiligo is critical in appropriate prognostication of the patient. In most cases, it is easy to recognize segmental vitiligo because of its patterned unilateral distribution; however, in some early and localized cases, where the diagnosis is uncertain, clinical criteria to differentiate segmental and nonsegmental, limited or focal vitiligo are required. Based on a previous descriptive study done in our department, a set of clinical criteria was proposed for the diagnosis of segmental vitiligo.[3] The present study is aimed at validating these diagnostic criteria for segmental vitiligo.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional analytical and diagnostic validation study conducted in the Department of Dermatology and Venereology of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India over a period of 4 years (2011–2015). Approval from the institute ethics committee was obtained and all patients provided informed consent. Patients with vitiligo having unilateral localized lesions or those with noncontiguous lesions with less than/equal to three body sites (either side of head/neck, trunk, upper limb and lower limb was considered as one site) were included in the study. Vitiligo patients with extensive bilateral vitiligo, those with involvement of more than three body sites and those with mixed vitiligo or pure mucosal vitiligo were excluded. A detailed history was elicited and clinical evaluation done for all the patients. Patients were classified as segmental or nonsegmental vitiligo using the proposed criteria [Table - 1]. Standard clinical photographs were taken of all the patients and sent for evaluation to three experts (VR, JS and AM), who were not a part of the previous descriptive study.[3] Opinion was sought from each expert independently, while they were blinded to the opinion of the other two experts. The opinion on the diagnosis as given by at least two out of three experts was considered the final diagnosis, and in the absence of any other specific parameters, this was regarded as the “gold standard.” In case of doubt, they classified cases as “not sure, maybe segmental vitiligo,” “not sure, maybe nonsegmental vitiligo” and “completely unsure, cannot say.”

Statistical analysis

A sample size of minimum 120 vitiligo patients was calculated to achieve 80% sensitivity and 80% specificity with 95% confidence interval (CI) and 10% absolute error margin. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and the negative predictive value of the proposed clinical criteria for segmental vitiligo were calculated using the experts' opinions as the reference. The agreement in the classifications between the experts' and clinical criteria was assessed using the kappa coefficient of agreement (k). A P < 0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analyses. The analysis was implemented on Stata version 12.1.

Results

Two hundred patients with vitiligo were included in the study. The age at onset varied from 6 months to 60 years with a median age at onset of 13 years. The mean disease duration was 53.09 ± 66.3 months (range: 1–480 months). Only a single site was involved in 178 patients, two sites in 19 patients and three sites in three patients. Therefore, 225 vitiliginous areas were further evaluated and each vitiliginous area was treated as an individual unit for quantitative evaluation. The clinical criteria were applied to all these 225 units and each vitiliginous area was classified as either segmental or nonsegmental vitiligo.

Clinical features

The vitiligo units affected the head and neck most commonly (n = 111, 49.3%) followed by trunk (n = 64, 28.4%), lower limb (n = 42 cases, 18.67%) and upper limb (n = 8, 3.5%). Fifty-nine lesions were represented by a single macule while 166 lesions were represented by multiple macules in the same segment. Leucotrichia was present in 126 (56%) lesions: 104 had leucotrichia within the depigmented macules (28 had leucotrichia <50% covering the lesion, while 76 had >50% involvement), while 10 lesions had leucotrichia outside the vitiligo lesions, and 12 had leucotrichia within as well as beyond the vitiligo lesions.

A patterned arrangement of vitiligo macules could be ascertained in 135 (60%) lesions: the definite patterns included blaschkoid (n = 65), dermatomal (n = 11) and phylloid (n = 2). Patterns in other cases were doubtful, such as oblong, linear and checkerboard. We also analyzed the 36 cases with patterned vitiligo lesions on the face, out of which 23 (63.89%) cases could be categorized according to Hann classification.[4] Type III (16.66%) was the most common pattern, followed by type Ia and type V (11.1% each).

Vitiligo classification: as per the clinical criteria and experts' opinions

Of the 225 units, 146 (64.9%) units were classified as segmental vitiligo and 79 (35.1%) as nonsegmental vitiligo as per the proposed clinical criteria.

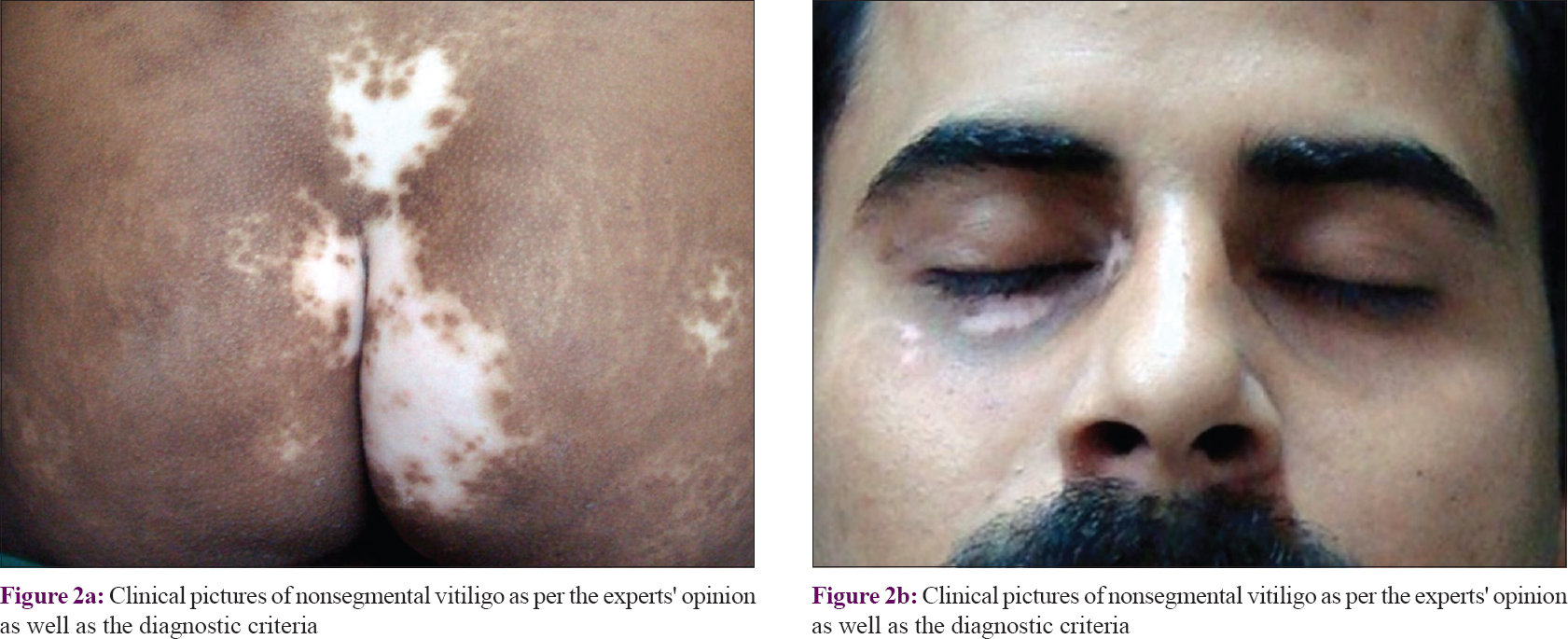

All three experts gave an opinion on all the 225 units. One hundred forty seven (65.3%) units were classified as “segmental vitiligo” [Figure - 1], and 39 (17.3%) units as “nonsegmental vitiligo” [Figure - 2] by at least two out of three experts. In eight (3.5%) units, diagnosis of “not sure, maybe segmental vitiligo” was made, whereas one (0.4%) unit were classified as “not sure, maybe nonsegmental vitiligo” consensually. In the remaining 30 units (13.3%), either no consensual diagnosis was made or consensually experts agreed that they are “completely unsure” [Figure - 3].

|

|

|

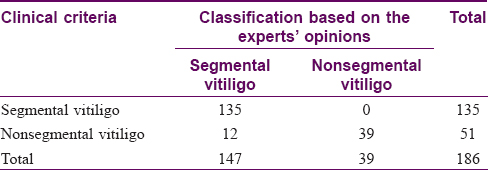

Performance of the clinical criteria against experts' opinions

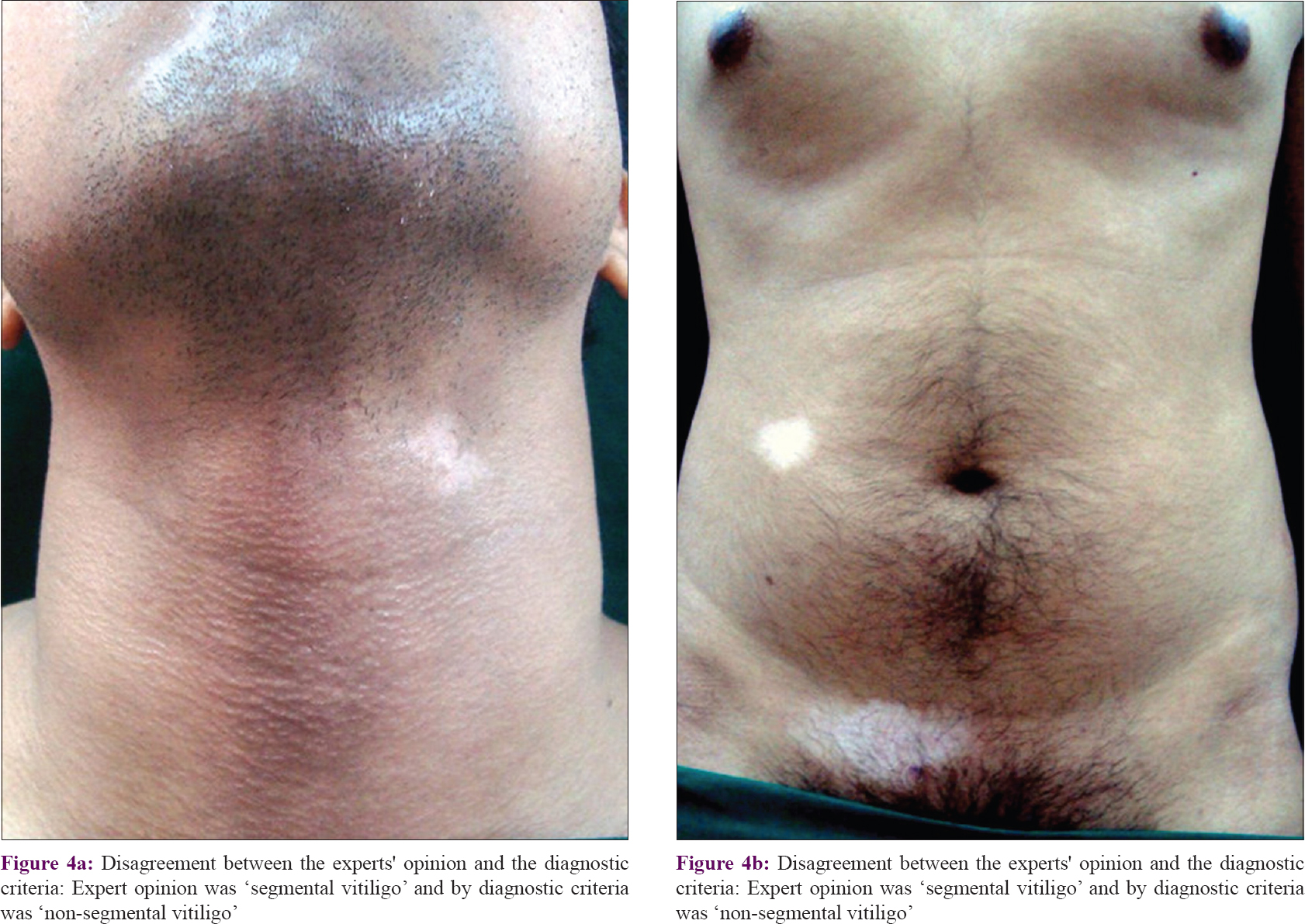

On comparing the clinical criteria with the “sure” units of segmental or nonsegmental vitiligo (n = 186) as per consensual experts' opinions [Table - 2], the sensitivity and specificity of the clinical criteria was found to be 91.8% (95% CI: 86.2%–95.7%) and 100% (95% CI: 91%–100%), respectively. The positive predictive value was 100% (95% CI: 97.3–100%), while the negative predictive value was 76.5% (95% CI: 62.5%–87.2%). There was 93.5% (95% CI: 89%–96.6%) agreement between the clinical criteria and experts' opinions (k = 0.83, P < 0.001) [Figure - 4]. Additionally, these measures of the clinical criteria were also calculated after including those units where experts were doubtful regarding vitiligo classification (n = 195). The performance of the diagnostic criteria was found to decrease slightly; sensitivity and specificity became 88.4% (95% CI: 82.3%–93%) and 97.5% (95% CI: 86.8%–99.9%) respectively, while the positive and negative predictive value were 99.3% (95% CI: 96%–100%) and 68.4% (95% CI: 54.8%–80.1%), respectively. The agreement between the clinical criteria and experts' opinions reduced to 90.3% (95% CI: 85.2%-–94%) with a kappa value of 0.74 (P < 0.001). We applied the clinical criteria even on units where the experts could not arrive at a consensual diagnosis or were “completely unsure” (n = 30). Of these, 22 (73.3%) units were classified as nonsegmental vitiligo and 8 (26.7%) as segmental vitiligo.

|

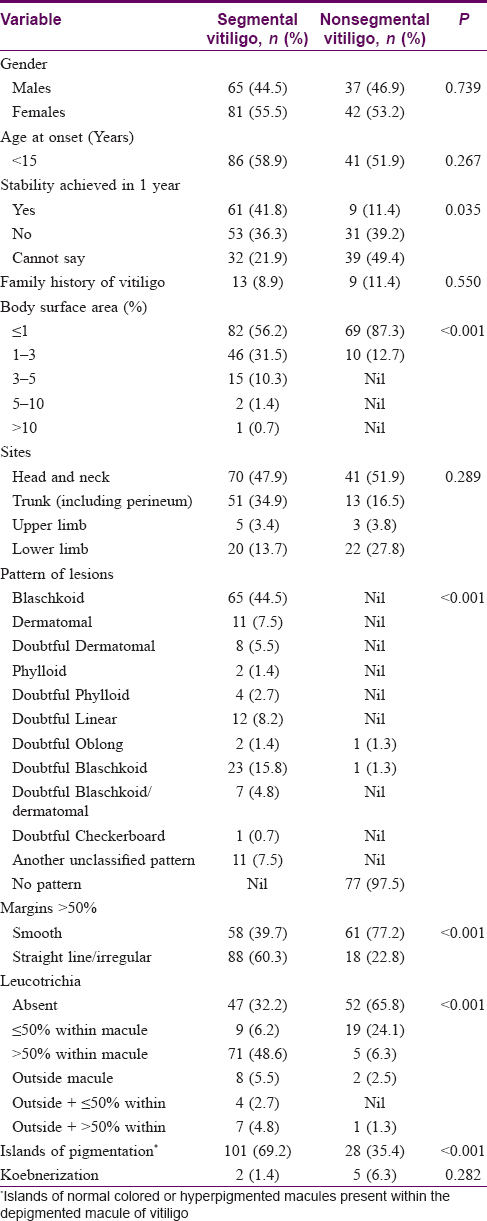

The demographic and clinical features of vitiligo lesions categorized as either segmental or nonsegmental vitiligo according to the proposed criteria are summarized in [Table - 3].

Discussion

There is limited data regarding the characterization of segmental vitiligo based on clinical features in various stages and its differentiation from early nonsegmental vitiligo. To date, there are no well-established clinical criteria for the diagnosis of segmental vitiligo, and a dermatologist's opinion is generally regarded as the “gold standard” in the absence of a validated diagnostic test.[5],[6] Based on an earlier study conducted in our department on 188 patients a set of criteria was proposed for the diagnosis of segmental vitiligo.[3] In this study, we compared these clinical criteria with the experts' opinions regarding the diagnosis of segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo.

The proposed diagnostic criteria for segmental vitiligo were found to have high sensitivity (91.8%) and specificity (100%) for the cases where the experts were sure of the diagnosis. On including those cases where experts were unsure of their diagnosis but were inclined to make a diagnosis of either segmental or nonsegmental vitiligo, the sensitivity and specificity of the criteria decreased only slightly. We applied the diagnostic criteria even in cases where experts were completely unsure of the diagnosis and could not classify cases as either segmental or nonsegmental vitiligo. Such a situation is not uncommonly encountered in clinical practice and was seen in 30/225 (13.3%) cases in our study. Amongst them, 22 cases were classified as nonsegmental vitiligo and 8 were classified as segmental vitiligo. Thus, these criteria may be useful in the diagnosis of even those cases where experts could not form an opinion on the diagnosis. Thus at present, where no validated diagnostic tool is available for segmental vitiligo, this set of criteria can aid the clinician in correctly diagnosing segmental vitiligo, especially in early cases when the diagnosis can be uncertain.

Segmental vitiligo often assumes a dermatomal or a quasi-dermatomal pattern, similar to herpes zoster. Even the involvement of the same or different dermatomes on both sides of the body, as seen in cross-segmental vitiligo or bilateral segmental vitiligo,[7] can rarely occur in herpes zoster (herpes zoster duplex bilateralis or symmetricus).[8] However, it is now well known that segmental vitiligo can have other patterns and is not always dermatomal or quasi-dermatomal.[3],[9],[10] Often, the segment affected by vitiligo involves parts of several dermatomes or follows the lines of Blaschko. We noticed various distribution patterns in our cases with segmental vitiligo—blaschkoid pattern was the most common, followed by dermatomal, linear, oblong, phylloid and checkerboard pattern. These patterns become more complex when observed on the face. Kim et al. initially classified segmental vitiligo on face into six types based on clinical observation and after about a decade, further modified their classification.[4] Though not one of the objectives of our study, we attempted to classify segmental vitiligo on the face in the initial 36 patients according to Hann classification.[4] We found type III to be the most common pattern, followed by type Ia and type V. This is in contrast to the study by Kim et al., where Ia was the most common pattern (28.8%), followed by types II, III, IV, mixed, Ib and V.[4] We could not classify about a third (n = 13/36, 36.11%) as per Hann classification, suggesting that further refinement in classification of segmental vitiligo over face may be needed to increase its applicability.

It is easy to differentiate between segmental vitiligo from generalized or widespread vitiligo, but the difficulty arises in distinguishing it from localized nonsegmental or focal vitiligo. We compared the available clinical data in these 200 patients (225 vitiliginous areas) with segmental and localized nonsegmental vitiligo who were diagnosed based on the proposed criteria. Patients with segmental vitiligo were found to have an earlier disease onset, as compared with nonsegmental vitiligo. Certain clinical features were more frequently observed in segmental vitiligo—disease stability at one year after disease onset, more body surface area affected, sharp or irregular lesional margin instead of a smooth margin, leucotrichia, and islands of hyperpigmented or normopigmented skin in between the vitiligo lesions. Interestingly, the extent of depigmentation was found to be more in segmental vitiligo as compared with nonsegmental vitiligo in our study. This can be explained in the context of vitiligo pattern; the area covered by vitiligo patch in a segmental distribution was more as compared with a few patches randomly scattered in nonsegmental vitiligo. This seemingly contrary observation as compared with previous studies can be explained by our inclusion criteria—we studied only patients with localized vitiligo, whereas earlier studies included cases with generalized vitiligo as well.[11] Thus in localized vitiligo, the likelihood of lesions being segmental vitiligo increases if more surface area is affected. Though the distinction from extensive or generalized vitiligo is seemingly straightforward, patients with localized nonsegmental or focal vitiligo may pose a diagnostic challenge. Therefore, we sought to test the performance of our diagnostic criteria for cases where dermatologists might be uncertain of the pattern, and a need for a diagnostic tool may be felt. Leucotrichia outside the vitiligo macule is seen in about 13% cases of segmental vitiligo, but this feature is almost exclusive to it. Nonetheless, we continue to consider it a minor criterion only because of its low incidence in our study. A history of koebnerization was more common in nonsegmental vitiligo, but no significant difference was seen on examination.

Limitations

In the absence of an established “gold standard” for the diagnosis of segmental vitiligo, we compared the performance of the diagnostic criteria with expert dermatologists' opinion.

Conclusions

The proposed criteria have good sensitivity, specificity and predictive values for the diagnosis of segmental vitiligo. These can aid the clinician in correctly diagnosing segmental vitiligo, and can be used in clinical as well as research settings.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal the identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Ezzedine K, Lim HW, Suzuki T, Katayama I, Hamzavi I, Lan CC, et al. Revised classification/nomenclature of vitiligo and related issues: The vitiligo Global Issues Consensus Conference. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2012;25:E1-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Taïeb A, Picardo M; VETF Members. The definition and assessment of vitiligo: A consensus report of the vitiligo European Task Force. Pigment Cell Res 2007;20:27-35.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Khaitan BK, Kathuria S, Ramam M. A descriptive study to characterize segmental vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:715-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Kim DY, Oh SH, Hann SK. Classification of segmental vitiligo on the face: Clues for prognosis. Br J Dermatol 2011;164:1004-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Aydin SZ, Maksymowych WP, Bennett AN, McGonagle D, Emery P, Marzo-Ortega H. Validation of the ASAS criteria and definition of a positive MRI of the sacroiliac joint in an inception cohort of axial spondyloarthritis followed up for 8 years. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:56-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Firooz A, Davoudi SM, Farahmand AN, Majdzadeh R, Kashani N, Dowlati Y. Validation of the diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 1999;135:514-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Lee HS, Hann SK. Bilateral segmental vitiligo. Ann Dermatol 1998;10:129-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Kantaria SM. Bilateral asymmetrical herpes zoster. Indian Dermatol Online J 2015;6:236.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:157-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Nordlund J. Genetic hypomelanosis: Acquired depigmentation. In: Norlund JJ, Boissy RE, Hearing VJ, King RA, Oetting WS, Ortonne JP, editors. The Pigmentary System: Physiology and Pathophysiology. 2nd ed. Malden, Massachussetts: Blackwell Science; 2006. p. 551.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Bezio S, Mahe E, Bodemer C, Eschard C, Viseux V, et al. Segmental and nonsegmental childhood vitiligo has distinct clinical characteristics: A prospective observational study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:945-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

9,820

PDF downloads

2,489