Translate this page into:

Vitiligo: Compendium of clinico-epidemiological features

2 Skin institute and School of Dermatology, Greater Kailash, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Virendra N Sehgal

A/6, Panchwati, Delhi - 110 033

India

| How to cite this article: Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Vitiligo: Compendium of clinico-epidemiological features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:149-156 |

Abstract

Vitiligo, an autoimmune disorder characterized by localized and / or generalized depigmentation of the skin and / or mucous membranes, is a well-recognized entity. The imperatives of its epidemiology both in rural India and in global reckoning have been highlighted frequently. Its morphology is striking and is characterized by asymptomatic ivory / chalky white macule(s) that may be frequently surrounded by a prominent pigmented border, the 'trichrome vitiligo'. However vitiligo may have morphological variations in the form of: trichrome, quadri-chrome, penta-chrome, blue and inflammatory vitiligo. Its current topographical classification into segmental, zosteriform and nonsegmental, areata, vulgaris, acrofacialis and mucosal represent its well acclaimed presentations. Its adult and childhood onset is well appreciated as also its presentation in males and females. Occasionally, it may be possible to identify triggering factors. Vitiligo may be associated with cutaneous, ocular and systemic disorders, the details of which are discussed in this article.

|

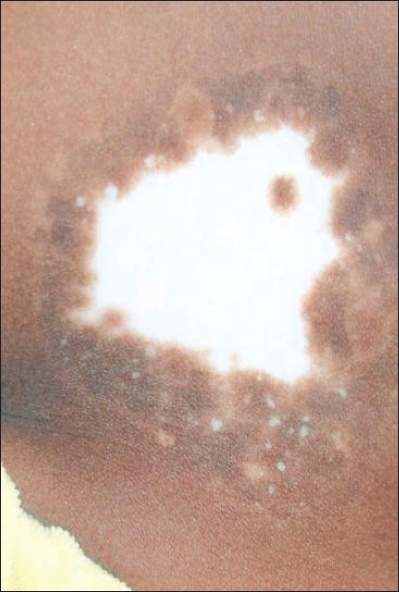

| Figure 5: Vitiligo areata: Localized chalky white discoloration |

|

| Figure 5: Vitiligo areata: Localized chalky white discoloration |

|

| Figure 4: (a-b) Segmental vitiligo: Vitiligo zosteriformis before and after PUVA therapy |

|

| Figure 4: (a-b) Segmental vitiligo: Vitiligo zosteriformis before and after PUVA therapy |

|

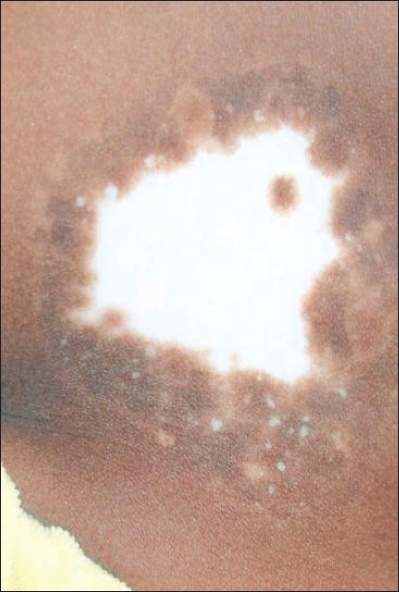

| Figure 3: Trichrome vitiligo: Localized chalky white discoloration with pigmentary interface between the normal and depigmented areas |

|

| Figure 3: Trichrome vitiligo: Localized chalky white discoloration with pigmentary interface between the normal and depigmented areas |

|

| Figure 2: Vitiligo vulgaris (generalized): Macules involving extensive body areas on the back |

|

| Figure 2: Vitiligo vulgaris (generalized): Macules involving extensive body areas on the back |

|

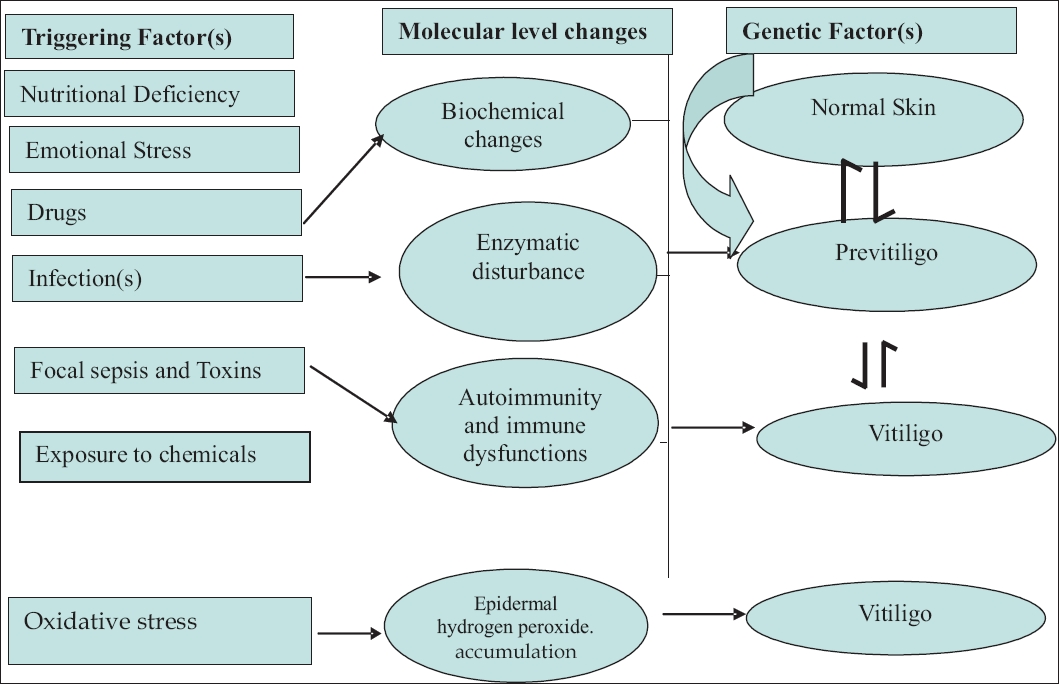

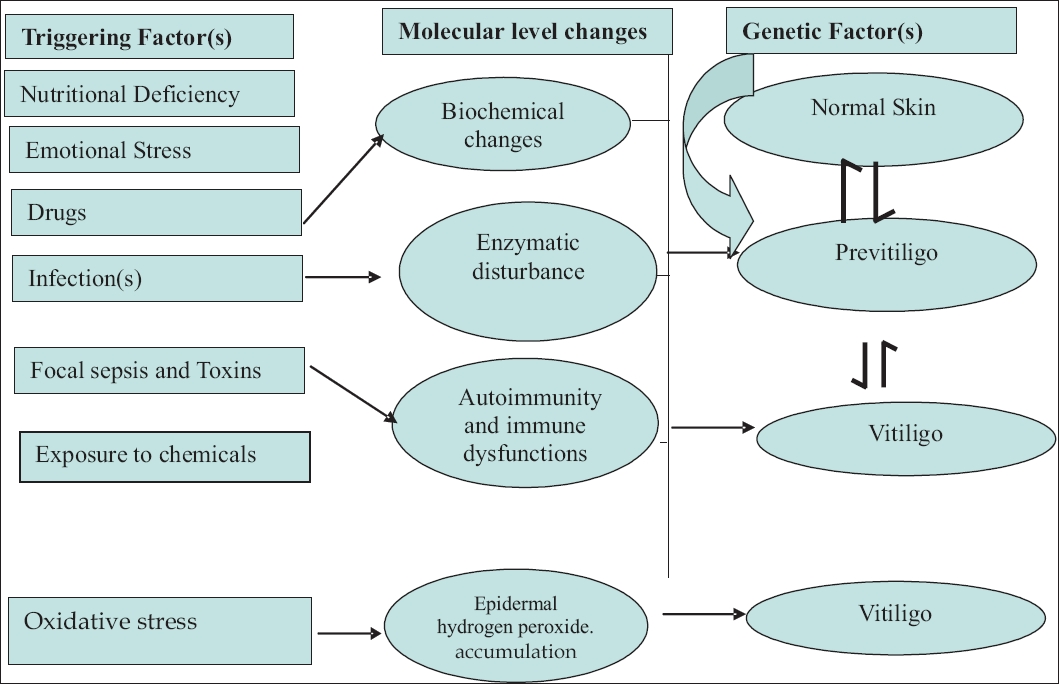

| Figure 1: Vitiligo triggering / precipitating factor(s);[65-68] and their possible role in its pathogenesis |

|

| Figure 1: Vitiligo triggering / precipitating factor(s);[65-68] and their possible role in its pathogenesis |

Reminiscences

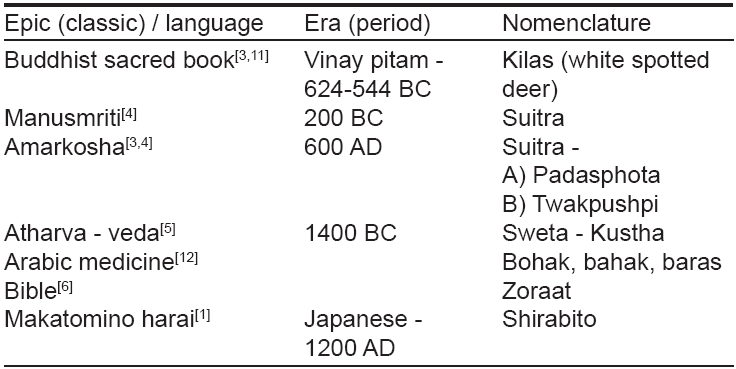

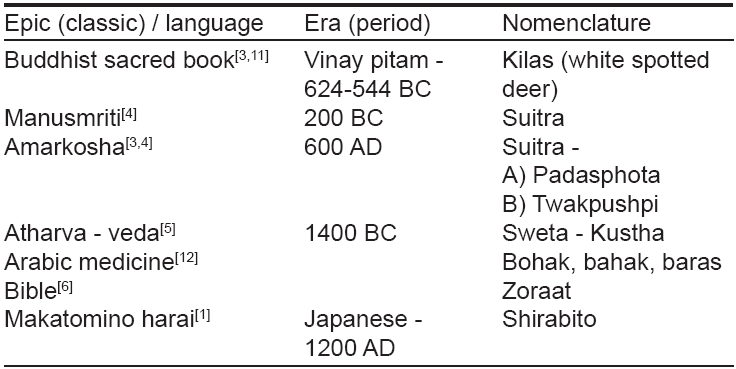

Vitiligo is an ancient malady and a historical background will facilitate continuity with current research. The earliest authentic reference of the condition can be traced back to the period of Aushooryan (2200 BC), in the classic Tarikh-e-Tib-e-Iran. [1] Pharonic medicine in the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BC) described two types of diseases affecting the color of the skin - (a) with tumors, probably leprosy and (b) with only color change, probably vitiligo. The latter was believed to be treatable. [2] Vitiligo occurs worldwide and since time immemorial, world literature is replete with references to the condition and different aspects of its causes and therapy. [3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10] Prior to its current nomenclature, it used to be pronounced by several other names, a short resume of which is formed in the following [Table - 1]. ′Vitiligo′ appears to have been derived from the Latin word ′vitium′, meaning a "defect" [13],[14] Documentation of the word "vitiligo" is present in the book, De-Mediccina, by the Roman physician Celsus. [15]

Definition

Vitiligo is a common, acquired, discoloration of the skin, characterized by well circumscribed, ivory or chalky white macules which are flush to the skin surface. In contrast to this, leukoderma refers to such macules wherein the cause of such a change is known. The hair over the lesion may be either normal or white (poliosis). [16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23]

Epidemiology

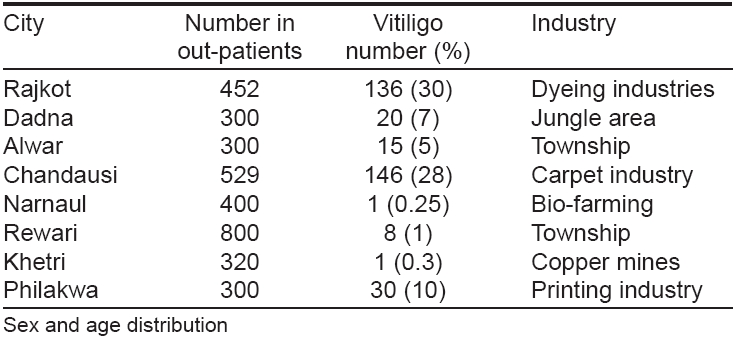

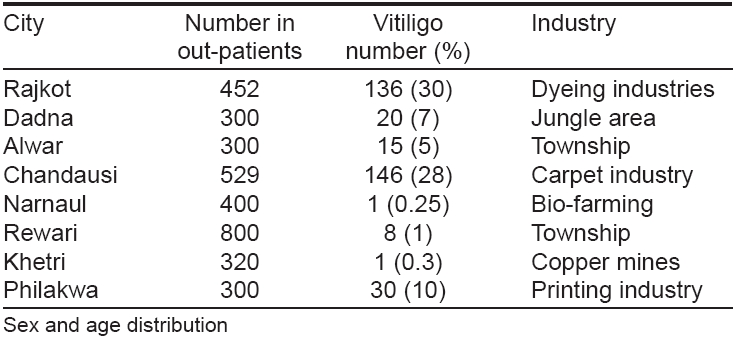

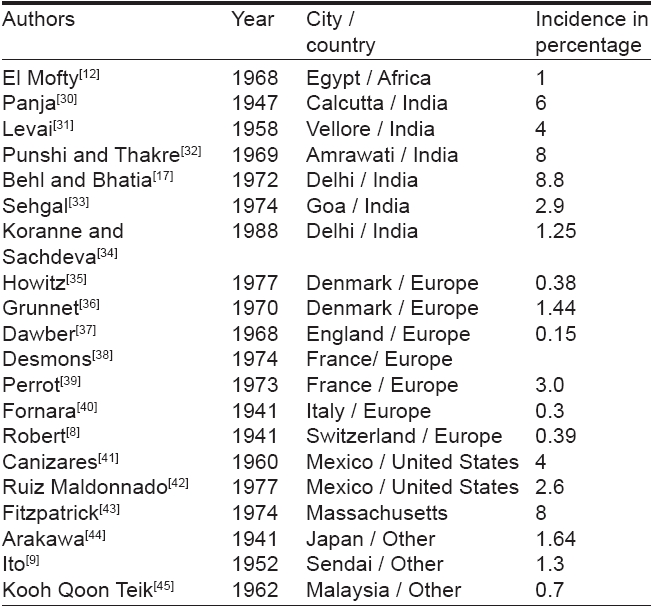

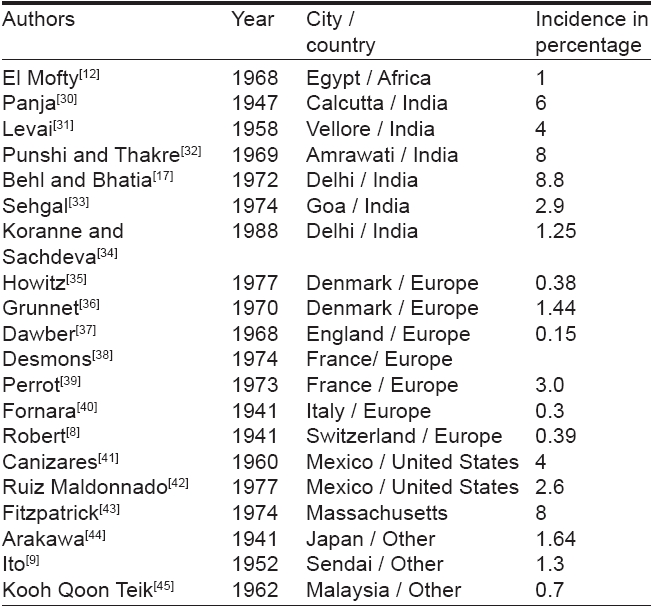

Vitiligo occurs worldwide with an overall prevalence of 1%. However, its incidence ranges from 0.1 to > 8.8% [11],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29] across the country and in different countries of the globe. The highest incidence of the condition has been recorded in Indians from the Indian subcontinent, followed by Mexico and Japan [Table - 2]. The difference in its incidence may be due to a higher reporting of vitiligo in a population, where an apparent color contrast and stigma attached to the condition may force them to seek early consultation. [30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45] Behl et al [11],[17] had organized camps in rural areas and industrial pockets in India to evaluate the status of vitiligo. Its incidence was found to be higher in villagers living near dyeing, printing, and carpet industries. A higher incidence of vitiligo in such areas [17] may be due to inclusion of cases with chemically induced depigmentation by industrial phenols and quinones, which might have a completely different pathomechanism. Its incidence, however, was relatively low amongst those residing adjoining copper-mines [Table - 3].

Adults and children of both sexes are equally affected although the greater number of reports among females is probably due to the greater social consequences to women and girls affected by this condition. [11],[24],[46],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52],[53] However, majority of the vitiligo cases reported begin during the period of active growth. Almost half the patients present before the age of 20 years and nearly 70-80% before the age of 30 years. [53],[54],[55],[56],[57],[58]

Family history

The proportion of patients with positive family history vary from one part of the world to another. In India, in particular, it ranges from 6.25-18%. In some studies it is as high as 40%. The mode of transmission of vitiligo is quite complex. It is probably polygenic with a variable penetrance. [53],[59],[60],[61],[62]

Triggering / precipitating factor(s)

It is difficult to precisely define the triggering factors for vitiligo. Nevertheless, it is essential to elicit the details of history of emotional stress, drug intake, infections, trauma / injury (Koebner′s phenomenon) [63] existent prior to the development of vitiligo lesions [24],[53],[64] [Figure - 1] attempts to bring into focus the various probable triggering factors in the natural history /development of vitiligo. It is believed that major oxidative stress occurs in vitiligo skin, which is evidenced by low catalase levels and cellular vacuolization in the epidermis [65],[66] Several factors may contribute to the oxidative stress, thus leading to the accumulation of epidermal hydrogen peroxide. The presence of the hydrogen peroxide can be demonstrated in vivo by using noninvasive Fourier transform Raman spectroscopy. [65],[66],[67],[68] A better understanding of these factors may prove to be helpful in the management of vitiligo.

Clinical Features

Vitiligo is characterized by the appearance of patchy discoloration evident in the form of typical chalky-white or milky macule(s) [Figure - 2]. The macules are round and / or oval in shape, often with scalloped margins. [24],[53] The size of the macules may vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters with the lesions affecting the skin and / or mucous membranes. By and large, the lesions are asymptomatic although itching / burning may precede or accompany the onset of the lesions in a few patients. [53],[69],[70],[71],[72],[73] Vitiligo is a slow and progressive disease and may have remissions and exacerbations correlating with triggering events. [53],[70],[74] Occasionally, the lesions of vitiligo may begin to form around a pigmented nevus [75] (Sutton′s nevus, leukoderma aquisitum centrifugum) and then go on to affect distant regions. [52],[73]

Although any part of the skin and / or mucous membranes is amenable to develop vitiligo, the disease has a predilection for normal hyperpigmented regions such as the face, groin, axillae, aerolae and genitalia. Furthermore, lesions may develop in other areas like the ankles, elbows, knees, which are subjected to repeated trauma / friction, an outcome of Koebner′s phenomenon. [63] In the event of extensive disease, the lesions are symmetrically distributed [76],[77],[78] with an exclusive dermatomal distribution or mucous membrane involvement. [53],[79],[80],[81] Lip-tip syndrome, another variant of vitiligo is characterized by depigmentation of the terminal phalanges and the lips.

Vitiligo may show morphological variations in the form of:

Trichrome vitiligo: It is recognized by the presence of a narrow to broad intermediate color zone between a vitiligo macule and normal pigmented surrounding skin [Figure - 3]. Hann et al. [82] had highlighted its clinical and histopathological characteristics and concluded that it is a variant of unstable vitiligo. Cockade-like vitiligo is a variant of trichrome vitiligo. [83]

Quadri-chrome vitiligo: It is a well-documented fourth color in vitiligo lesions, usually seen in darker skin phenotypes. A macular perifollicular or marginal hyperpigmentation is its salient feature and denotes a repigmenting disease. [53]

Penta-chrome vitiligo: It is an infrequently encountered variant in which there is a sequential display of white, tan, brown, blue-gray hyperpigmentation and the normal skin. Black-skinned individuals are predisposed to have this disorder. [84]

Blue vitiligo: It usually corresponds to vitiligo macules occurring at the site of postinflammatory hypermelanosis. Ivkar et al. [85] reported the development of extensive blue vitiligo following the simultaneous progression of vitiligo and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patient.

Inflammatory vitiligo: It is an entity which may reveal an erythematous, raised border in a vitiligo macule with frequent itching and / or burning. These changes could be induced by aggressive therapy. [69],[86],[87]

Classification

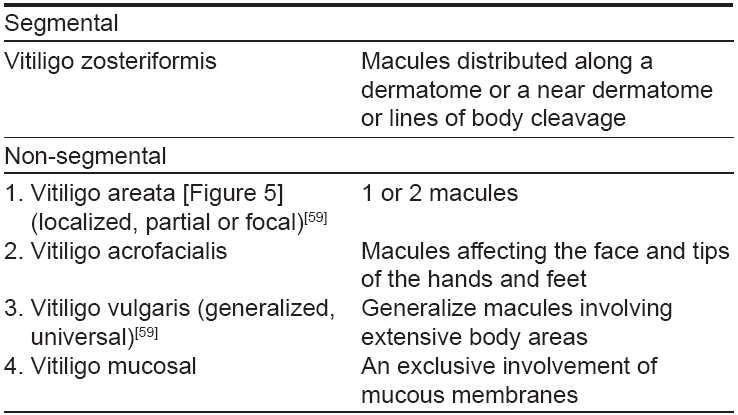

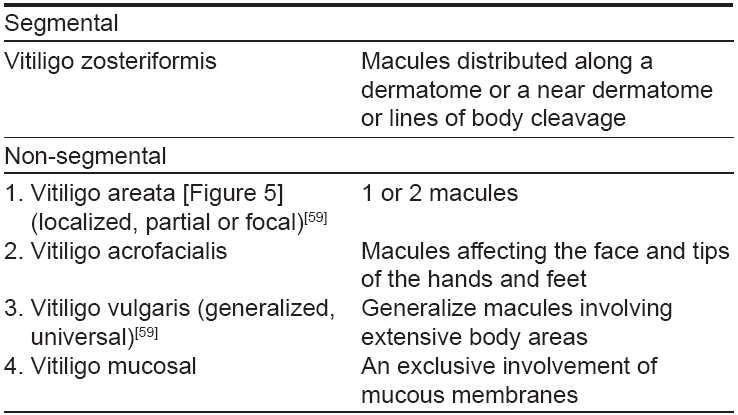

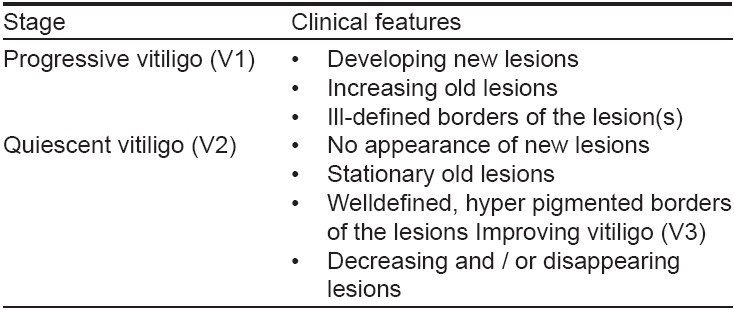

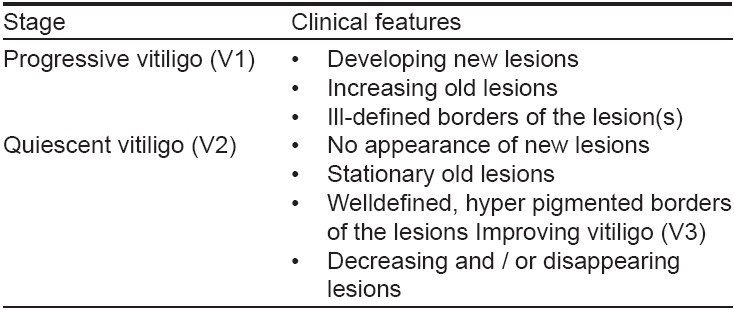

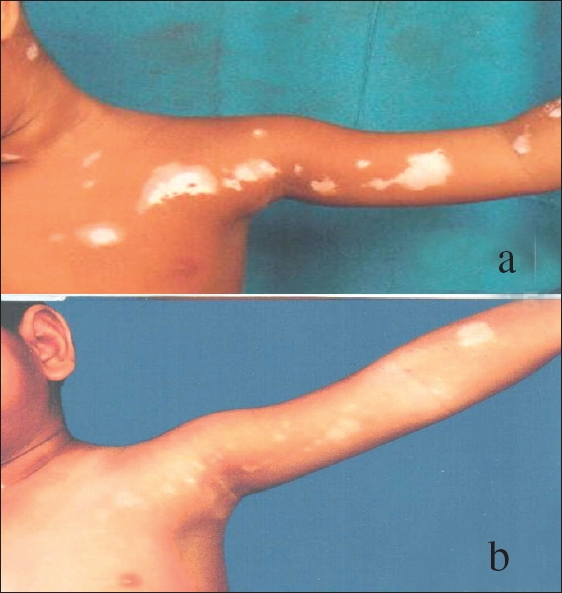

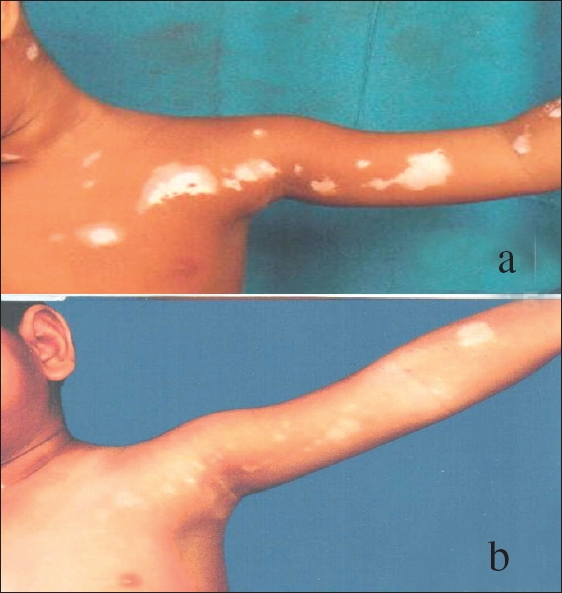

Vitiligo is classified into focal, segmental, generalized and universal types, a conventional self-explanatory arrangement. [24],[53],[59] However, Lerner [59] classified vitiligo into 3 groups namely: a) segmental [Figure - 4], localized, partial or focal vitiligo corresponding to a dermatome / adjacent dermatomes b) vitiligo vulgaris generalized, involving the hands, face, axillae and limbs and c) complete, total or universal vitiligo involving the entire or nearly entire body surface. Behl [53] et al. had introduced another classification which took cognizance of clinical stage(s) of vitiligo purported to assist or support its management [Table - 4].

Based on sweat stimulation studies, Koga and Tango divided vitiligo into types A and B. [88] Type A was nondermatomal and was considered to be an autoimmune disease that responded to steroids. On the other hand, type B (dermatomal) had shown sympathetic dysfunctions and responded to nialamide. Jerret and Szabo [89] had classified vitiligo into absolute and partial (subtypes I and II) depending upon complete or partial absence of melanocytes. After studying the pattern of vitiligo in the Indian context, [16],[32],[90] we suggest a topographical classification that is helpful in deciding the treatment and prognosis [Table - 5].

Associations of Vitiligo

Cutaneous associations

It is important to recapitulate associations of vitiligo as they commonly provide circumstantial evidence to its possible etiopathogenesis. Premature graying of the hair, leukotrichia, halo nevus, lichen planus and alopecia areata are frequently reported associations. [90],[91],[92],[93],[94],[95],[96],[97] Of these, leukotrichia (poliois) is found in up to 45%, premature graying of the hair (canities) in 37%, followed by halo nevus in 35% and alopecia areata in up to 10% of cases. [24],[53],[55],[59] Occasionally, other skin disorders like dermatitis herpetiformis, giant congenital melanocytic nevus with neurotization, chronic urticaria, nevus depigmentosus, polymorphic light eruption and malignant melanoma have also been recorded in association with vitiligo. [98],[99],[100],[101],[102] Furthermore, psoriasis vulgaris confined to vitiligo patches and occurring contemporaneously in the same patient has recently been described [103] Other interesting autoimmune associations include morphea and Hashimoto′s thyroiditis. [104] While presenting strong direct and indirect evidence of the autoimmune etiology of alopecia areata, Hordinsky and Ericson, [105] stressed its association with vitiligo in many patients.

Ocular associations

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome [106],[107],[108],[109],[110],[111] refers to the full constellation of vitiligo, poliosis and alopecia with panuveitis and auditory and neurological manifestations. However, iris and retinal pigmentary abnormalities may be present as isolated findings in a few vitiligo patients. Although visual acuity is unaffected in such patients, choroidal abnormalities may be detected in up to 30% and iritis in 5% of vitiligo patients. [90] Infrequently, choroidal halo nevus may be associated. [112],[113],[114]

Systemic associations

Systemic disorders like hypo / hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus, Addisons′ disease, pernicious anemia, lymphoma, leukemia and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) are a few of the diseases associated with vitiligo. [86],[90],[107],[108],[109],[115],[116],[117] Egli and Walter [118] recently highlighted the association of vitiligo with pernicious anemia while Federman et al. [119] recorded the occurrence of ulcerative colitis in Vogt Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Other significant associations include Sjogren syndrome, [120] giant cell myocarditis, [121] plexopathy [122] and amelanotic melanoma. [123] Autoimmunity in children and adolescents with vitiligo was studied by Kurtev and Dourmishev to discover its possible role in the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. [124] Autoimmunity and immune responses are of paramount significance in vitiligo, a detailed discussion of which can be found elsewhere. [125]

Childhood (juvenile) vitiligo

Morphological characteristics in childhood (juvenile) vitiligo are more or less identical to those of adult onset vitiligo. Interestingly, there has been a steady increase in the incidence of childhood vitiligo [126] during the past 2 decades.

Differential Diagnosis

Numerous dermatoses enter into the differential diagnosis of vitiligo. [91] Pityriasis versicolor, nevus depigmentosus, tuberous sclerosis, idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, Waadenberg′s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, leprosy [tuberculoid tuberculoid (TT) [126] borderline tuberculoid (BT), borderline borderline (BB)], melanoma-associated leukoderma, chemical leukoderma, piebaldism and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome [90],[127],[128],[129],[130],[131] are some of these dermatoses.

Natural Course

The natural course of vitiligo is highly unpredictable. However, after an abrupt onset, the disease may slowly progress for some time followed by a period of stability, which may last for several months to decades. A few of the cases may once again start progressing at a rapid pace after a period of dormancy. Such an occurrence is not uncommon in nonsegmental vitiligo types namely vitiligo vulgaris, acrofacialis and areata. Vitiligo zosteriformis / segmental, however, is the most stable form and may show a better prognosis. [86],[87],[88],[89],[90] In addition, several other factors may assist in evaluating its prognosis a) the younger the patient, the shorter the duration, the better is the prognosis, b) the lesions located on the fleshy regions of the body may show better chance of recovery in contrast to that on bony / friction points and c) the presence of leukotrichia or lesions on mucous membranes or mucocutaneous junctions may account for a poor prognosis. [86]

| 1. |

Najamabadi M. Tarikh-e-Tib-e-Iran. Vol I. Shamsi: Tehran; 1934.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Ebbel B. The Papyrus Ebess Copenhagen. Levin and Munksgaard: 1937. p. 45

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Charaka S, editor. With translation by the Shree Gulabkunverba Society, Volume 4. Chikitsa Sthana: Jamnagar, India; 1949.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Sushrut S, Bhishagratna KK. Vol I, Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan: Varanasi; 1963. p. 354.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Whitney WD. Atharva-Veda Samhita. Harvard Oriental series. Vol 7, Harvard University Press: Cambridge; 1905.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Goldman L, Moraites RS, Kitzmiller KW. White spots in biblical times. A background for the dermatologist for participation in discussions of current revisions of the bible. Arch Dermatol 1966;93:744-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Bateman TA. Practical synopsis of cutaneous disease. Johnson J: London; 1813.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Robert P. Uber die 'Vitiligo'. Dermatologica 1941;4:257-319.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Ito M. Vitiligo. Tohoku J Exp Med 1952;5:72-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Banarjee BN, Pal BK. Leukoderma. Int J Dermatol 1956;2:1-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Srivastava G. Vitiligo- Introduction Asian Clinic. Dermatol 1994;1:1-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

El Mofty AM. Vitiligo and psoralens. Pergamon Press: Oxford; 1968. p. 1147-95.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Carter RL, editor. A Dictionary of Dermatologic Terms. 4 th ed. Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, 1992.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Fitzpatrick TB. Hypomelanosis. South Med J 1964;57:995-1005.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Nair BK. Vitiligo-a retrospect. Int J Dermatol 1978;17:755-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Sehgal VN. Vitiligo. Textbook of clinical Dermatology. 4 th ed. Jaypee: New Delhi; 2004. p. 99-101.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Behl PN, Bhatia RK. 400 case of vitiligo - A clinico therapeutic analysis. Indian J Dermatol 1971;17:51-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Punshi SK. Vitiligo. Q Med Rev 1979;30:1-46.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

el Mofty AM, el Mofty M. Vitiligo - a symptom complex. Int J Dermatol 1980;19:237-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Klaus S, Lerner AB. Vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;11:997-1000.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Scholtz JR. Vitiligo. Arch Dermatol 1985;121:21-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Dunn JF Jr. Vitiligo. Am Fam Physician 1986;33:137-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Sharquie KE. Vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol 1984;9:117-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Shwartz RA, Janniger CK. Vitiligo. Cutis 1997;60:239-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Hann SK, Park YK, Chun WH. Clinical feature of vitiligo. Clin Dermatol 1997;15:891-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Kovacs SO. Vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;38:647-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Agarwal G. Vitiligo: An under - estimated problem. Fam Pract 1998;15:519-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Handa S, Kaur I. Vitiligo - Clinical findings in 1436 patients. J Dermatol Tokyo 1999;26:653-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, Bennett DC, Spritz RA. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res 2003;16:208-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Panja G. Leukoderma. Indian J Vener Dis 1947;13:56-63.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Levai M. A study of certain contributory factors in the development of vitiligo in South Indian patients. AMA Arch Derm 1958;78:364-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Punshi SK, Thakre RD. Skin survey. Maharashtra Med J 1969;16:535-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Sehgal VN. A clinical evaluation of 202 cases of Vitiligo. Cutis 1974;14:439-45.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Koranne RK, Sachdeva KG. Vitiligo. Int J Dermatol 1988;27:676-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Howitz J, Brodthagen H, Scheartz M, Thomsen K. Prevalence of Vitiligo. Epidemiological survey on the isle of Bornholm, Denmark. Arch Dermatol 1977;113:47-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Grunnet I, Howitz J, Reymann F, Schwartz M. Vitiligo and pernicious anemia. Arch Dermatol 1970;101:82-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Dawber RP. Vitiligo in Mature onset diabetes mellitus. Br J Dermatol 1968;80:275-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Desmons MF. Le vitiligo de Ie'nfant. Bull Soe FR. Dermatol Syphilgr 1974;81:526-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Perrot H. Vitiligo, Thyreopallisis et autominunization. Lyon. Med 1973;30:325-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Fornara I. Quoted by Robert P. Uber die vitiligo. Dermatologica 1941;4:241-319.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Canizares O. Geographic dermatology: Mexico and Central America. Arch Dermatol 1960;82:870-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Ruiz-Maldonado R, Tamayo Sanchez L, Velazquez E. Epidemiology of skin diseases in 10,000 patients of pediatric age. Bol Med Hosp Infant Max 1977;34:137-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Fitzpatrick TB. Phototherapy of vitiligo, in sunlight and man. Normal and abnormal biologic response. In : Pathak MA, editor. University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo; 1974. p. 783-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Arakawa A. Quoted by Robert P. Uber die Vitiligo, Dermatologica 1941;84:257-319.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Khoo OT. Vitiligo. A review and report of treatment of 60 cases in the general hospital, Singapore, from 1954 to 1958. Singapore Med J 1962;3:157-68.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Le Poole C, Boissy RE. Vitiligo. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1997;16:3-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Hann SK, Lee HJ. Segmental vitiligo clinical findings in 208 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35:671-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Zaima H, Koga M. Clinical course of 44 cases of localized type vitiligo. J Dermatol 2002;29:15-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Jeninger CK. Childhood vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 1993;51:25-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Halder RM. Childhood Vitiligo. Clin Dermatol 1997;15:899-906.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Cho S, Kang KC, Hahm JH. Characteristics of vitiligo in Korean children. Pediatr Dermatol 2000;17:189-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 52. |

Handa S, Dogra S. Epidemiology of childhood vitiligo: A study of 625 patients from North India. Pediatr Dermatol 2003;20:207-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 53. |

Behl PN, Aggarwal A, Srivastava G. Vitiligo In : Behl PN, Srivastava G, editors. Practice of Dermatology. 9 th ed. CBS Publishers: New Delhi; 2003. p. 238-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 54. |

Herane MI. Vitiligo and leukoderma in children. Clin Dermatol 2003;21:283-95.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 55. |

Jaigirdar MQ, Alam SM, Maidul AZ. Clinical presentation of vitiligo. Mymensingh Med J 2002;11:79-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 56. |

Engel L. What are those white patches in my patient's skin? Dermatol Nurs 2001;13:292-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 57. |

Lerner MR, Fitzpatrick TB, Halder RM, Hawk JL. Discussion of a case of vitiligo. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 1999;15:41-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 58. |

Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Vitiligo-it is important. Arch Dermatol 1982;118:5-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 59. |

Lerner AB. Vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol 1959;32:285-310.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 60. |

Westerhof W. Vitiligo-a window in the darkness. Dermatology 1995;190:181-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 61. |

Goudie BM, Wilkieson C, Goudie RB. Skin maps in vitiligo. Scott Med J 1983;28:343-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 62. |

Gauthier Y, Cario-Andre M, Lepreux S, Pain C, Taieb A. Melanocyte detachment after skin friction in non lesional skin of patients with generalized vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:95-101.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 63. |

Pegum JS. Vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 1996;134:373.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 64. |

Behl PN. Review of therapeutic measures in the treatment of vitiligo. Indian J Dermtol Venereol 1957;23:17-24.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 65. |

Schallreuter KU, Moore J, Behrens-Williams S, Panske A, Harari M. Rapid initiation of re-pigmentation in vitiligo with dead sea climatotherapy in combination with pseudo catalase. Int J Dermatol 2002;41:482-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 66. |

Schallreuter KU. Successful treatment of oxidative stress in vitiligo. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 1999;12:132-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 67. |

Ortonne JP. Psoralen therapy in vitiligo. Clin Dermatol 1989;7:120-35.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 68. |

Orecchia G, Perfett L. Phototherapy with topical khellin and sunlight in vitiligo. Dermatology 1992;184:120-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 69. |

Arata J, Abe-Matsuura Y. Generalized vitiligo preceded by a generalized figurate erythematosquamous eruption. J Dermatol 1994;21:438-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 70. |

Abdel-Naser MB, Ludwig WD, Gollnick H, Orfanos CE. Non segmental vitiligo decrease of the CD45RA+ T-cell subset and evidence for peripheral T-cell activation. Int J Dermatol 1992;31:321-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 71. |

Nordlund JJ. The signification of depigmentation. Pigment Cell Res 1992;2:237-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 72. |

Al'Abadie MS, Warren MA, Bleehen SS, Gawkrodger DJ. Morphologic observations on the dermal nerves in vitiligo:an ultrastructural study. Int J Dermatol 1995;34:837-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 73. |

Fisher AA. Differential diagnosis of idiopathic vitiligo from contact leukoderma. Part II: Leukoderma due to cosmetics and bleaching creams. Cutis 1994;53:232-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 74. |

Goudie RB, Spence JC, Mackie R. Vitiligo patterns stimulating autoimmune and rheumatic diseases. Lancet 1979;2:393-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 75. |

Wayne DM, Helwig EB. Halo nevi. Cancer 1968;22:69-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 76. |

Wee TA. A case report of extensive vitiligo. Hawaii Med J 1997;56:37-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 77. |

Drake L, Dinehart SM, Farmer ER, Goltz RW, Graham GF, Hordinsky MK, et al . Guidelines of care for vitiligo patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35:620-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 78. |

Hann SK, Chun WH, Park YK. Clinical characteristics of progressive vitiligo. Int J Dermatol 1997;36:353-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 79. |

Hautmann G, Panconesi E. Vitiligo: A psychologically influencing disease. Clin Dermatol 1997;15:879-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 80. |

Mathias CG, Maibach HI, Conant MA. Perioral leukoderma stimulating vitiligo from use of toothpaste containing cinnamic aldehyde. Arch Dermatol 1980;116:1172-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 81. |

O'Sullivan JJ, Stevenson CJ. Screening for occupational vitiligo in workers exposed to hydroquinone monomethyl ether and to para tertiary-amyl-phenol. Br J Ind Med 1981;38:381-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 82. |

Hann SK, Kim YS, Yoo JH, Chun YS. Clinical and histological characteristic of trichrome vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:589-96.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 83. |

Dupre A, Christol B. Cockade - like vitiligo and linear vitiligo a variant of Fitzpatrick's trichrome vitiligo. Arch Dermatol Res 1978;262:197-203.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 84. |

Fargnoli MC, Bolognia JL. Pentachrome vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33:853-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 85. |

Ivker R, Goldaber M, Buchness MR. Blue vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:829-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 86. |

Michaelsson G. Vitiligo with raised borders- report of two cases. Acta Derm Venereol 1968;48:158-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 87. |

Fisher AA. Differential diagnosis of idiopathic vitiligo: Part III: Occupational leukoderma. Cutis 1994;53:278-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 88. |

Koga M, Tango T. Clinical features and course of type A and type B vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 1988;118:223-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 89. |

Jarrett A, Szabo G. The pathological varieties of vitiligo and their response to treatment with meladinine. J Dermatol 1956;68:313-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 90. |

Sehgal VN, Rege VL, Mascarenhas F, Kharangate VN. Clinical pattern of vitiligo amongst Indians. J Dermatol Tokyo 1976;3:49-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 91. |

Ortonne JP, Bahadoran P, Fitzpatrick TB. Hypomelanoses and hypermelanosis. In : Freeberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen K F, Gold Smith LA, Katz SI, Fitzpatrick TB, editors. Dermatology in general medicine. Mc Graw-Hill: New York; 1999. p. 836-47.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 92. |

Adams BB, Lucky AW. Colocalization of alopecia areata and vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol 1999;16:364-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 93. |

Smyth JR Jr, McNeil M. Alopecia areata and universalis in the Smyth-chicken model for spontaneous autoimmune vitiligo. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 1999;4:211-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 94. |

Khandpur S, Reddy BS. An association of 20 nails dystrophy with vitiligo. J Dermatol 2001;28:38-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 95. |

Lee D, Lazova R, Bolognia JL. A figurate papulosquamous variant of inflammatory vitiligo. Dermatology 2000;200:270-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 96. |

Wayte J, Wilkinson JD. Unilateral lichen planus sparing the vitiliginous skin. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:817-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 97. |

Anstey A, Marks R. Co-localization of lichen planus and vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 1993;128:103-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 98. |

Amato L, Gallerani I, Fuligni A, Mei S, Fabbri P. Dermatitis herpetiformis and vitiligo: Report of a case and review of the literature. J Dermatol 2000;27:462-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 99. |

De Sica AB, Wakelin S. Psoriasis vulgaris confined to vitiligo patches and occurring contemporaneously in the same patients. Clin Exp Dermtol 2004;29:434-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 100. |

Dervis E, Acbay O, Barut G, Karaoglu A, Ersoy L. Association of vitiligo, morphea and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:236-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 101. |

Hordinsky M, Ericson M. Autoimmunity: Alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2004;9:73-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 102. |

Shin JH, Kim MJ, Cho S, Whang KK, Hahm JH. A case of giant congenital nevocytic nevus with necrotization and on set of vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2002;16:384-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 103. |

Midelfart K, Moseng D, Kavli G, Stenvold SE, Volden G. A case of chronic urticaria and vitiligo, associated with thyroiditis, treated with PUVA. Dermatologica 1983;167:39-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 104. |

Kang IK, Hann SK. Vitiligo coexistent with nevus dedepigmentosus. J Dermatol Tokyo 1996;23:187-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 105. |

Downs AM, Lear JT, Dunnill MG. Polymorphic light eruption limited to areas of vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:379-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 106. |

IX. Malignant melanoma and vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol 1979;73:491-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 107. |

Nordlund JJ, Albert D, Forget B, Lerner AB. Halo nevi and Vogt Koyanagi- Harada syndrome - manifestation of vitiligo. Arch Dermatol 1980;116:690-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 108. |

Kumakiri M, Kimura T, Miura Y, Tagawa Y. Vitiligo with an inflammatory erythema in Vogt - Koyanagi- Harada disease: Demonstration of filamentous masses and amyloid deposits. J Cutan Pathol 1982;9:258-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 109. |

Barnes L. Vitiligo and Vogt Koyanagi- Harada syndrome. Dermatol Clin 1988;6:229-39.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 110. |

Egli F, Walter R. Images in clinical medicine. Vitiligo and pernicious anemia. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2698.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 111. |

Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Ruser CB, Judson PH, Kirsner RS. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome and ulcerative colitis. South Med J 2004;97:169-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 112. |

Okada T, Sakamoto T, Ishibashi T, Inomata H. Vitiligo in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: Immunohistological analysis of inflammatory site. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1996;234:359-63.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 113. |

Tsuruta D, Hamada T, Teramae H, Mito H, Ishii M. Inflammatory vitiligo in Vogt-Koyanagi- Harada disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:129-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 114. |

Fournier GA, Albert DM, Wagoner MD. Choroidal halo nevus occurring in a patient with vitiligo. Surv Opthalmol 1984;28:671-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 115. |

Kim YC, Park HJ, Cinn YW. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIa with generalized vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:1028-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 116. |

Fisher AA. The role of ocular disturbance in the differentiation of idiopathic vitiligo from contact leukoderma. Cutis 1995;55:61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 117. |

Feinstein A, Kahana M, Schewach-Millet M, Levy A. Idiopathic calcinosis and vitiligo of the scrotum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;11:519-20.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 118. |

Stork J, Nemcova D, Hoza J, Kodetova D. Eosinophilic fasciitis in an adolescent girl with lymphadenopathy and vitiligo-like and linear scleroderma-like changes. A case report. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1996;14:337-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 119. |

Montes LF, Pfister R, Elizalde F, Wilborn W. Association of vitiligo with Sjogren's syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol 2003;83:293.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 120. |

Stevens AW, Grossman ME, Barr ML. Orbital myositis, vitiligo and giant cell myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35:310-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 121. |

Stollberger C, Finsterer J, Angel K, Eggl-Tyl E. Unusual cause of leg oedema and plexopathy in a patient with vitiligo. Acta Med Austriaca 2000;27:160-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 122. |

Takematsu H, Tomita Y, Sato A, Seiji M. An amelanotic melanoma transformed into melanotic melanoma with development of vitiligo. J Dermatol Tokyo 1981;8:431-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 123. |

Sehgal VN. Clinical leprosy. 4 th ed. Jaypee Brothers: New Delhi; 2004.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 124. |

Kurtev A, Dourmishev AL. Thyroid function and auto-immunity in children and adolescents with vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2004;18:109-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 125. |

Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Vitiligo: Auto-immunity and immune responses. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:583-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 126. |

Halder RM, Grimes PE, Cowan CA, Enterline JA, Chakrabarti SG, Kenney JA Jr. Childhood vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;16:948-54.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 127. |

Verma S, Kumar B. Contact leukoderma of the scalp or an unusal variant of vitiligo. J Dermatol 2001;28:554-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 128. |

Silvestre JF, Botella R, Ramon R, Guijarro J, Betlloch I, Morell AM. Periumbilical contact vitiligo appearing after allergic contact dermatitis to nickel. Am J Contact Dermatitis 2001;12:43-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 129. |

Kossard S, Commens C. Hypopigmented malignant melanoma simulating vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:840-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 130. |

Sanchez JL, Vazquez M, Sanchez NP. Vitiligolike macules in systemic scleroderma. Arch Dermatol 1983;119:129-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 131. |

Saha KC, Arya M, Saha AK. Neurohistological studies in lichen planus and vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol 1979;24:51-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

16,428

PDF downloads

3,516