Translate this page into:

Vitiligoid lichen sclerosus: A reappraisal

2 Department of Dermatology, Ninewells University Hospital and Medical School, Dundee, United Kingdom

Correspondence Address:

Venkat Ratnam Attili

Visakha Institute of Skin and Allergy, Marripalem, Visakhapatnam - 530 018, Andhra Pradesh

India

| How to cite this article: Attili VR, Attili SK. Vitiligoid lichen sclerosus: A reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:118-121 |

Abstract

Background: Many case studies of lichen sclerosus (LS) have reported an association of vitiligo. However, such an association is not reported from larger case studies of vitiligo, which happens to be a common disease. Autoimmune etiology suspected in both LS and vitiligo has been considered as the reason for their association in some patients. It has also been suggested that lichenoid inflammation in LS may trigger an autoimmune reaction against melanocytes. Aims: To test this association, we reviewed clinical and histological features of 266 cases of vitiligo and 74 cases of LS in a concurrent study of both diseases. Methods: All outpatients seen in our department between 2003 and 2006 and who were diagnosed as having LS or vitiligo on the basis of clinical and pathologic features were included in the study. Results: Vitiligoid lesions were seen along with stereotypical LS lesions in three patients but all the three lesions had histological features of LS. Oral/genital areas were affected in 57 out of the 74 LS cases and of those, 15 were initially suspected to have vitiligo. These cases with a clinical appearance of vitiligo and histological features of LS were considered as 'vitiligoid LS', a superficial variant proposed by J. M. Borda in 1968. Association of LS was not observed in the 266 cases of vitiligo. Conclusion: Exclusive oral/genital depigmentation is a common problem and histological evaluation is essential to differentiate vitiligoid LS from true vitiligo. The association of vitiligo with LS may have been documented due to the clinical misdiagnosis of vitiligoid LS lesions as vitiligo as histological investigations were not undertaken in any of the reported cases.

|

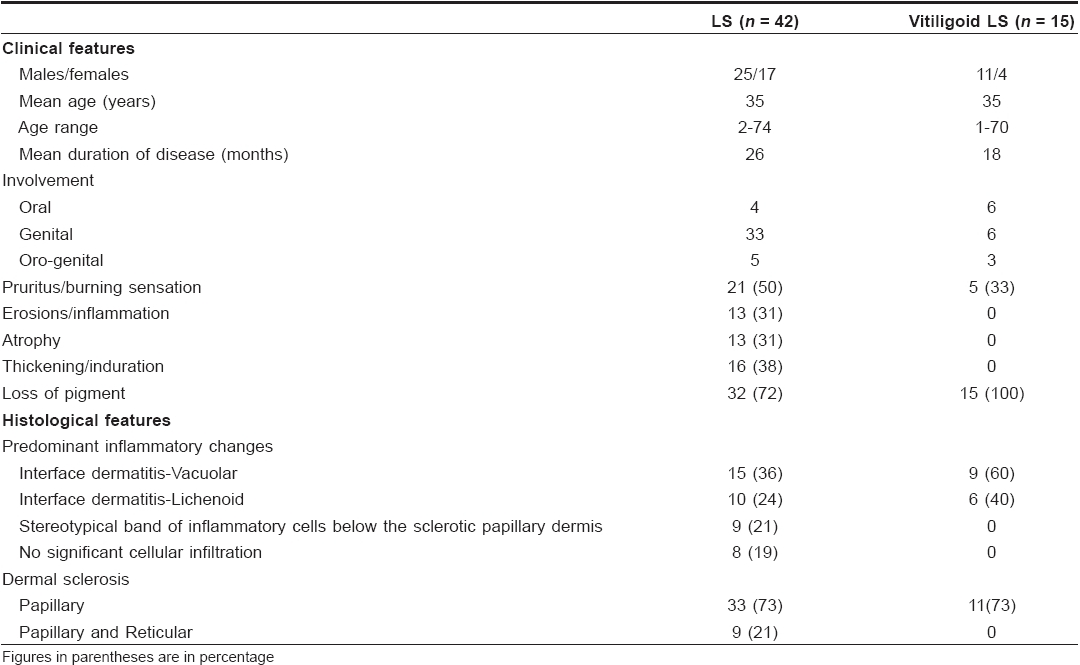

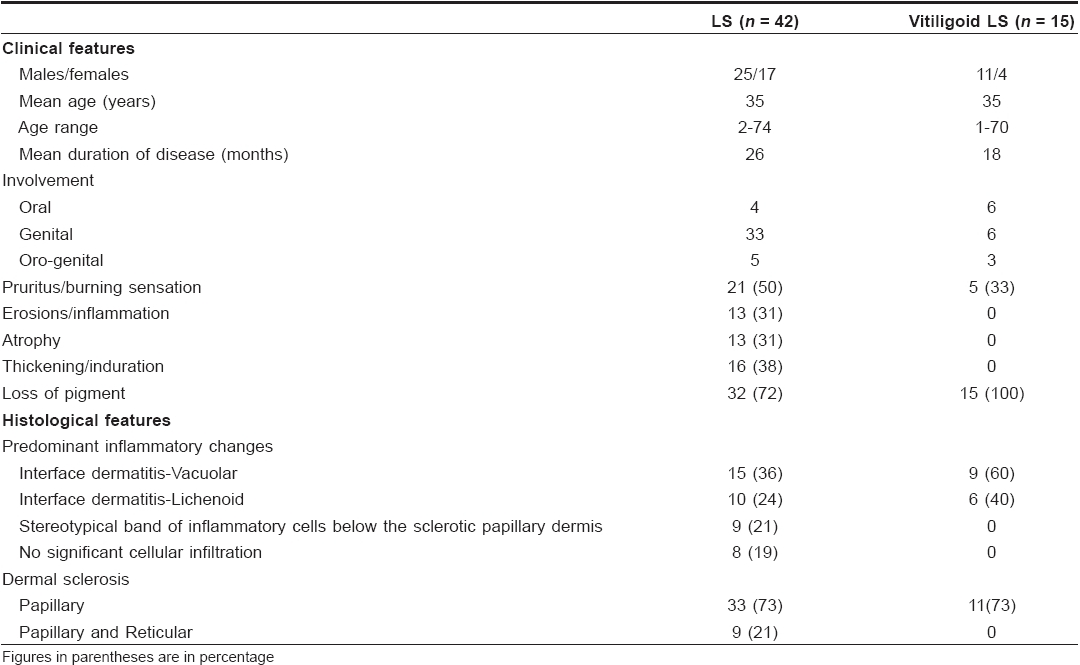

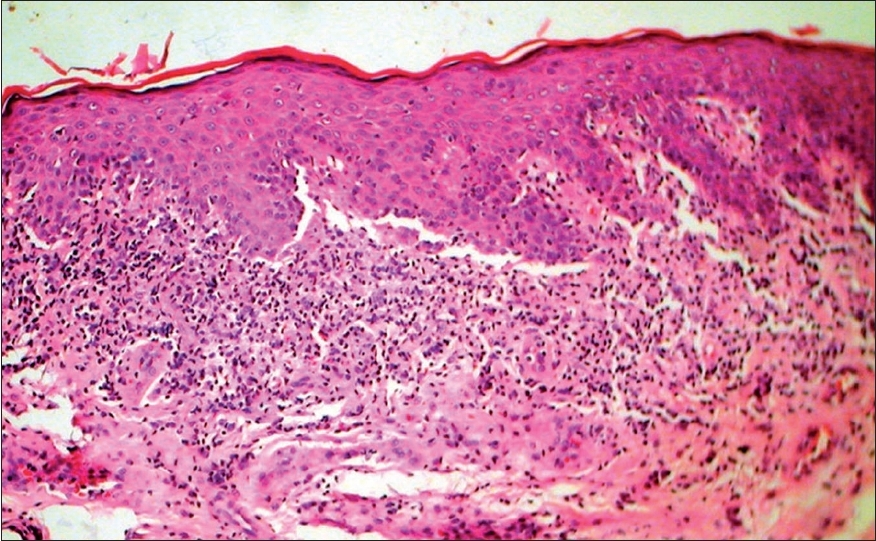

| Figure 4: Vitiligoid lichen sclerosus - Late lesion with papillary dermal sclerosis (H and E stain, � 400) |

|

| Figure 4: Vitiligoid lichen sclerosus - Late lesion with papillary dermal sclerosis (H and E stain, � 400) |

|

| Figure 3: Late vitiligoid lichen sclerosus lesion with spreading vitiligoid margins and papillary dermal selerosis as shown in Figure 4 |

|

| Figure 3: Late vitiligoid lichen sclerosus lesion with spreading vitiligoid margins and papillary dermal selerosis as shown in Figure 4 |

|

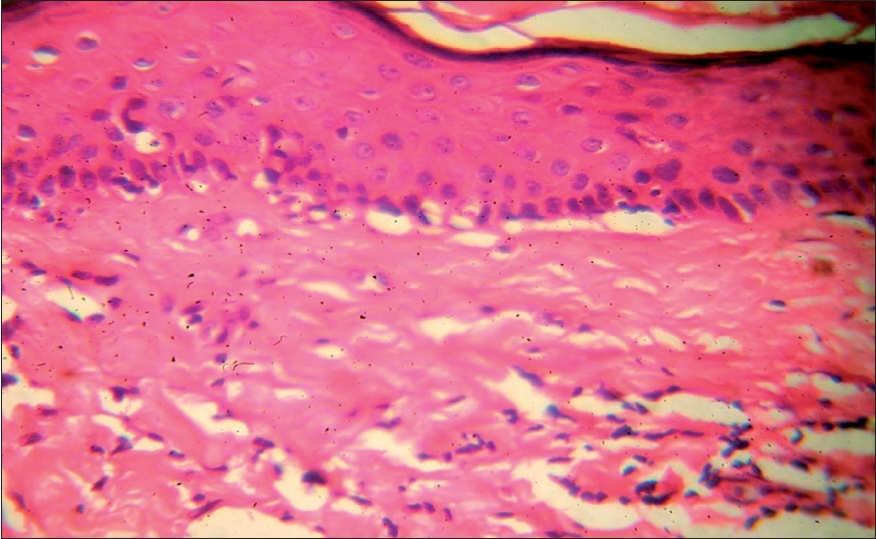

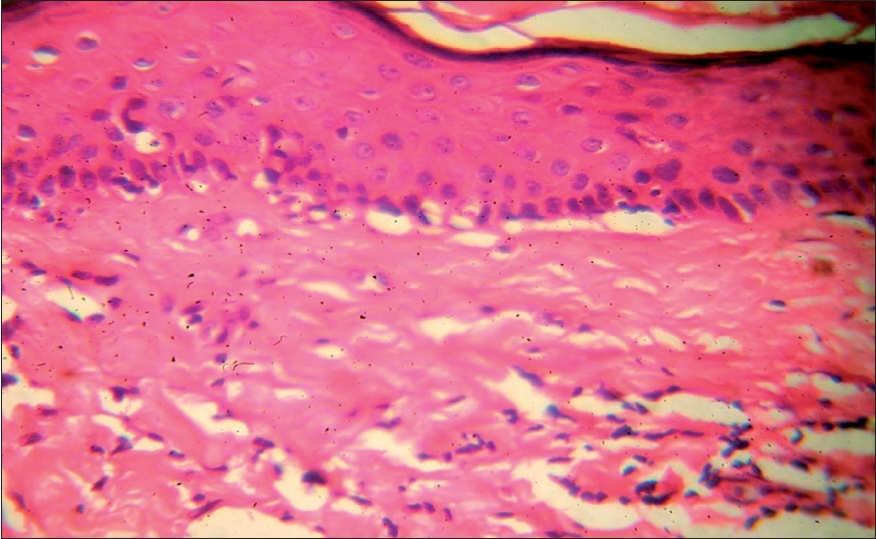

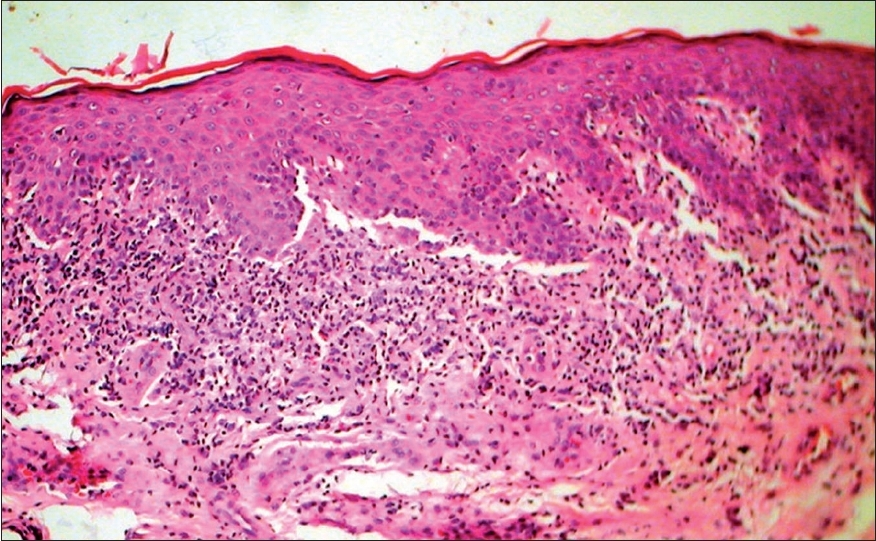

| Figure 2: Vitiligoid lichen sclerosus with a diffuse band of cellular infi ltrate at the interface along with vacuolar changes (H and E stain, � 150) |

|

| Figure 2: Vitiligoid lichen sclerosus with a diffuse band of cellular infi ltrate at the interface along with vacuolar changes (H and E stain, � 150) |

|

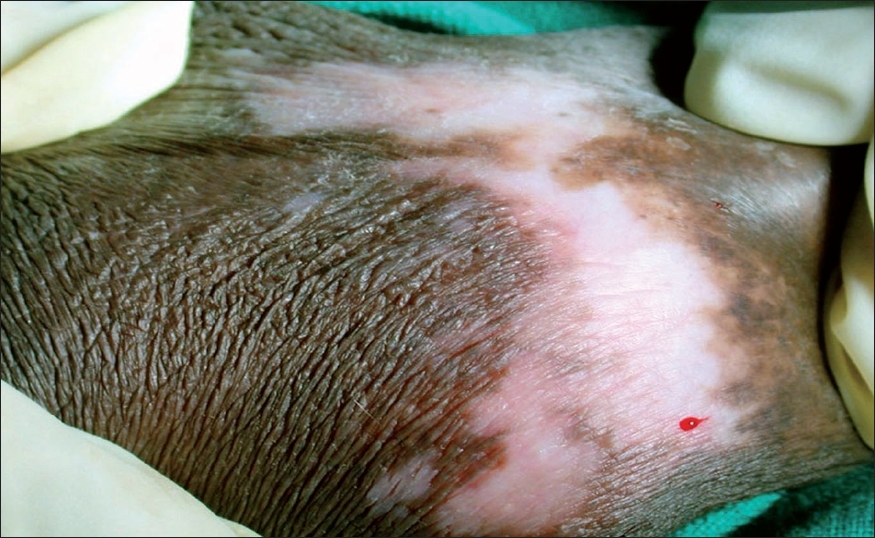

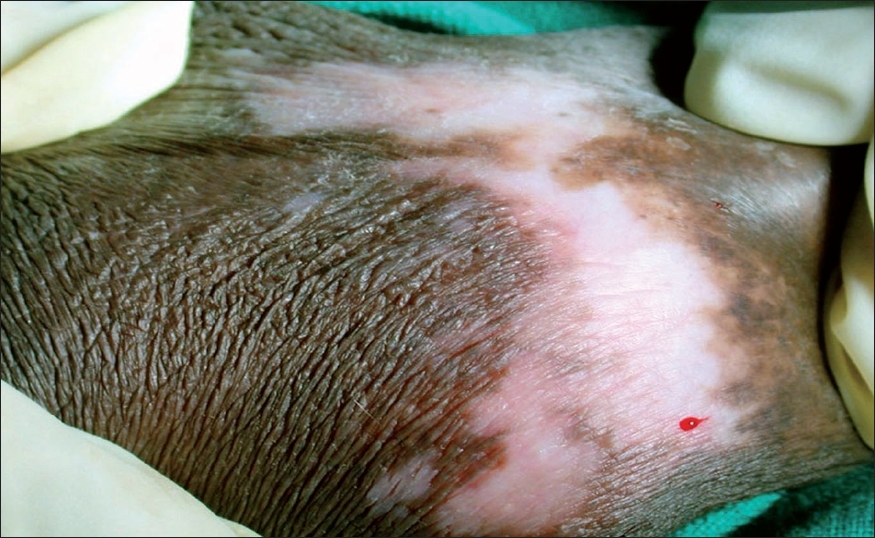

| Figure 1: Evolving genital lichen sclerosus with vitiligoid appearance and lichenoid interface dermatitis on biopsy as shown in Figure 2 |

|

| Figure 1: Evolving genital lichen sclerosus with vitiligoid appearance and lichenoid interface dermatitis on biopsy as shown in Figure 2 |

Introduction

Wallace reviewed 380 cases of LS and reported the association of plaque morphea as being significant and that of vitiligo as being probably significant. [1] While major opinion now favors LS as a superficial form of morphea because coexistence in the same patient and co-localization of the two within the same lesion has been reported, [2],[3],[4] probable reasons for the association of LS and vitiligo have not been explored. However, such an association is not inconceivable, [5],[6],[7] since autoimmune mechanisms have been suspected in the etiology of the two diseases. Pigment loss in LS is also a common observation and lichenoid inflammatory changes are proposed as an explanation by way of decreased melanin production or melanocyte destruction. These inflammatory changes triggering an autoimmune reaction to melanocytes have also been suggested as the common pathogenic connection that underlies the documented association of LS with vitiligo. [8] Interestingly, while association of vitiligo has been reported from case studies of LS, such an association is not reported from larger case studies of vitiligo which happens to be a much more common disease. [9],[10],[11],[12],[13] The issue also becomes contentious since Borda proposed ′Vitiligoid LS′ as a superficial variant [14] in which the clinical appearance is that of vitiligo and diagnosis primarily depends on histological features. The purpose of this study was to investigate the true association of LS and vitiligo in a large series of patients.

Methods

We have been studying vitiligo and vitiligoid lesions concurrently at our institute for 4 years, beginning from 2003. A total number of 266 new cases of vitiligo and 74 new cases of LS were seen by the end of 2006. In all cases, biopsies were routinely taken and histological features were correlated with the clinical features. LS was diagnosed and classified based on histopathological features as early evolving, fully developed and late lesions. [15] Vitiligo was diagnosed after histological exclusion of postinflammatory depigmentation due to other diseases. Wherever coexistence of the two diseases was suspected, biopsies were taken from representative areas of both the lesions. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained multiple sections were examined. Special stains were not considered essential for diagnosis [1] and as such were not employed.

Results

Of the 74 LS cases, nongenital skin was exclusively involved in 17 and oral/genital involvement was seen in 57. In the latter group, a good correlation between clinical and histological features was seen in 42 cases.

Vitiligoid LS: The remaining 15 cases were diagnosed as vitiligoid LS as these were clinically suspected to be vitiligo and the diagnosis of LS was made only after histological review. Lesions were considered as ′early evolving′ in ten, ′fully developed′ in three and two were ′late resolved′ lesions [Figure - 1],[Figure - 2],[Figure - 3],[Figure - 4]. Exclusive oral involvement (essentially limited to lips) was seen in six patients, genital involvement in six and both oral and genital involvement was seen in three patients. In the last group, similar clinical and histopathogical features were observed in both areas.

Among 74 LS cases, three had vitiligoid patches in association with genital LS lesions. Histological features in all the three vitiligoid lesions were indicative of LS. One of these patients had several vitiligoid patches along with a typical LS plaque lesion in the groin which also had a large spreading vitiligoid margin. A biopsy from this marginal area revealed diffuse lichenoid interface dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of early LS [Figure - 2].

Clinical and histological review of 266 vitiligo cases did not reveal association with LS. Fifteen had exclusive orogenital involvement which did not show interface dermatitis or papillary dermal sclerosis as seen in the vitiligoid LS cases.

Discussion

Male dominance of LS was observed in this study of a selection of cases from a dermatology clinic while other studies have shown female preponderance. Clinical profiles of patients with stereotypical LS and vitiligoid LS were similar [Table - 1] with the exception that vitiligoid LS lesions were far less symptomatic and of shorter duration. Early genital lesions of LS were more often associated with intense pruritus and erosions while late resolved lesions were associated with either atrophy or induration. Along with such textural changes, pigment loss in LS lesions was also a frequent observation. In contrast, pigment loss was the presenting complaint in vitiligoid LS with no significant textural changes or pruritus, which therefore mimicked common vitiligo. However, histopathological differentiation was not difficult. Pathognomonic papillary sclerosis was seen in late lesions and interface dermatitis of lichenoid or vacuolar type was seen in early cases [Figure - 2],[Figure - 4].

Interestingly, spreading vitiligoid margins were also seen in typical LS lesions and thus depigmentation appears to be an early manifestation. Pigment loss was a prominent feature in both early and late resolved lesions of vitiligoid LS in this study, which suggests that the associated degenerative changes make pigment loss irreversible. Progressive stereotypic genital LS lesions are characterized by increasing papillary sclerosis, which may extend to involve the upper reticular layer as well with a band of inflammatory cells beneath the sclerotic layer. In comparison, the characteristic histological changes in all cases of vitiligoid LS were strictly limited to the papillary layer confirming Borda′s assertion that it is a superficial variant. Although this entity was proposed in 1968, as far as we are aware, this is the only study that reiterates the importance of ′vitiligoid LS of Borda′ as a common problem in orogenital areas. Review of dermatological literature suggests that exclusive oral LS cases are rare whereas several have been reported by orofacial surgeons. [16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22] Exclusive orogenital lesions are also seen in vitiligo and it is possible that dermatologists, in the absence of histopathological review, favor a clinical diagnosis of vitiligo which is more common. On the flip side, it is also possible that the documented association of vitiligo with LS may have been due to clinical misdiagnosis of vitiligoid LS as none had taken biopsies from vitiligoid lesions. Such association did not stand the scrutiny of histopathological review in this study. Awareness that vitiligoid lesions may coexist with stereotypical lesions of LS and exclusive orogenital presentation of vitiligoid LS is essential for proper management.

| 1. |

Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus and atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc 1971;57:9-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Continuing medical education: Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;32: 393-416.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Sehgal VN, Srivatsava G, Aggarwal AK, Behl PN, Choudhary M, Bajaj P. Localised scleroderma/Morphea. Int J Dermatol 2002;41:467-75.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Peterson LS, Nelson AM, Daniel Su WP. Classification of Morphea (Localized Scleroderma). Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70:1068-76.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, Black MM. The association of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmune-related disease in males. Br J Dermatol 1983;109:661-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Harrington CI, Dunmore IR. An investigation into the incidence of auto-immune disorders in patients with lichen sclerosus and atrophicus. Br J Dermatol 1981;104:653-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, Mcgibbon DH, Black MM. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: A study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol 1988;118:41-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Carlson JA, Grabowski R, Mu XC, Del Rosario A, Malfetano J, Slominski A. Possible mechanisms of hypopigmentataion in lichen sclerosus. Am J Dermatopathol 2002;24:97-107.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Sehgal VN. A clinical evaluation of 202 cases of Vitiligo. Cutis 1974;14:439-45.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Dutta AK, Mandal SB. A clinical study of 650 cases of Vitiligo and their classification. Indian J Dermatol 1969;14:103.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Behl PN, Bhatia RK. 400 cases of Vitiligo: A clinico-therapeutic analysis. Indian J Dermatol 1972;17:51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Vinay S, Kalpana S, Sangeetha A. Vitiligo: A monograph and color atlas. 1 st ed. Fulford: Mumbai; 2000.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Sehgal VN, Srivatsava G. Vitiligo: Compendium of clinico-epidemiological features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:149-56.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Borda JM, Abulafia J, Jaimovich L. Syndrome of circumscribed sclero-atrophies. Derm Ibero Lat Am 1968;3:179-202.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Ackermann AB, Boer A, Bennin B, et al . Related net content on LSA. In : Histologic diagnosis of inflammatory skin diseases. Ardor Scribendi Ltd: New York; 2005.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Macleod RI, Soames JV. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the oral mucosa. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991;29:64-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Siar CH, Ng KH. Oral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Oral Med 1985;40:148-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

de Ara�jo VC, Orsini SC, Marcucci G, de Ara�jo NS. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1985;60:655-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Buajeeb W, Kraivaphan P, Punyasingh J, Laohapand P. Oral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;88:702-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Schulten EA, Starink TM, van der Waal I. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus involving the oral mucosa: Report of two cases. J Oral Pathol Med 1993;22:374-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Jensen T, Worsaae N, Melgaard B. Oral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002;94:702-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Mendonca EF, Ribeiro-Rotta RF, Silva MA, Batista AC. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med 2004;33:637-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

10,131

PDF downloads

2,376