Translate this page into:

Quality of life among schoolchildren with acne: Results of a cross-sectional study

2 Institute of Dermatovenereology, Clinical Center of Serbia; Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia,

3 Health Center "Euromedik", Belgrade, Serbia,

4 Institute of Social Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia,

5 Institute of Medical Statistics and Informatics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia,

Correspondence Address:

Slavenka Jankovic

Institute of Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Vi�egradska 26, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia

| How to cite this article: Jankovic S, Vukicevic J, Djordjevic S, Jankovic J, Marinkovic J. Quality of life among schoolchildren with acne: Results of a cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:454-458 |

Abstract

Background: Acne is a common problem in adolescent children and has a considerable impact on their quality of life. Aims: The purpose of this study was to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among Serbian adolescents with acne, using 2 questionnaires: The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) and the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) and to provide a cross validation of 2 scales. Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted among the pupils of the secondary railway-technical school in Belgrade, Serbia. 478 pupils (aged 15 - 18 years) completed 2 HRQoL questionnaires: CDLQI and CADI. We used t-test for differences between mean values of CDLQI and CADI and Spearman's rho coefficient for correlation between 2 questionnaires. Results: Self-reported acne was present in 71.6% of pupils (64.3% boys and 35.7% girls). The overall mean CDLQI score (4.35 of max. 30) and the overall mean CADI score (3.57 of max. 15) were low, indicating a mild impairment of HRQoL among adolescants. There was good correlation between the 2 questionnaires (Spearman' rho = 0.66). Conclusion: The CADI and the CDLQI questionnaires represent simple and reliable instruments for the assesment of HRQoL among schoolchildren with acne. In this study, we identified 17% of boys and 18% of girls perceived their acne as a major problem. It is important to detect and treat such adolescents on time to reduce the psychosocial burden associated with acne.Introduction

Acne is a common disease affecting 85% of teenagers. Most frequently, acne occurs on the face and in the long term, can produce cutaneous scarring and psychological impairment. The disease occurs in a psychologically labile period when adolescents usually have a desire to look their best. Previous studies have reported dissatisfaction with appearance, embarrassment, self-consciousness, and lack of self confidence in acne patients. [1] Acne, also, may have negative impact on personal relationships, sports activities, and employment opportunities in teens and young adults. [2],[3] The management of acne must take into account the impact of acne on the patient′s quality of life. [1] This is important, in particular, because there are effective therapies of acne, and administration of these agents can cause an improvement in quality of life and psychological health. [4],[5] Increased awareness and early intervention for the psychological and psychiatric sequelae of acne can benefit patients. Measurement of QoL changes gives insight into the impact of acne from a patient′s perspective and can also be a measure of treatment success.

There are several ways for the assessment of health related quality of life (HRQoL) among patients with acne. Either global scales or specific scales for acne can be used. Clinical trials indicate that use of global and specific scale together has complementary benefits. [1]

The aims of our study were to assess HRQoL among teenage schoolchildren with acne and to compare 2 HRQoL questionnaires: The Children′s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) and the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). According to our knowledge, similar research was not conducted in our country.

Methods

This cross-sectional study comprised of pupils aged 15 - 18 years who attended the secondary railway technical school in Belgrade, Serbia. Data were collected over 5 days in May 2010. The pupils were asked to fill in anonymously 3 self-reported questionnaires: The CDLQI, the CADI, and a short demographic questionnaire, which included questions on sex, age, family history, presence of acne and any other coexisting skin disease. The CDLQI is a specific questionnaire for the HRQoL assessment of children with skin disease. It contains 10 questions relating to feelings and emotions, personal relationships, free time activities, activities at school and on holiday, sleep quality and acne therapy. The format of the questions relates only to the previous week to avoid recall bias. Each question has 4 possible answers with a maximum of 3 points and a total maximum score of 30. Higher scores indicate more severely affected HRQoL. The CADI is a brief, acne-specific questionnaire, which also measures the impairment of QoL of children with acne. It is a descriptive questionnaire with 5 questions relating to feelings, symptoms, social life and perceived severity in the previous month. Each question has 4 possible answers with a maximum of 3 points and a total maximum score of 15. Higher scores indicate more severely affected QoL.

In this study, after obtaining permission from the copyright owner (Prof. Andrew Y Finlay), we used linguistically validated Serbian versions of CDLQI and CADI questionnaires. [6],[7]

All 869 pupils (ages 15 - 18 years) of the railway-technical school in Belgrade were selected for participation. Both, the principal of the school and parent′s council gave agreement for the study to be conducted during teaching time. An explanatory letter describing the purpose of the study was sent to the home address of each pupil, and their parents were required to provide consent by signing on the letter. Written informed consent was obtained for 478 out of 869 pupils (response rate of 55%). Participation was voluntary, and pupils were free to refuse to complete the questionnaire if they wished. Ethics committee permission was not obtained since studies with no research intervention do not need ethics committee approval.

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The differences between mean values of total CDLQI and total CADI were assessed by t-test. For correlation between the questionnaires, Spearman′s rho coefficient was used. A 2-tailed probability value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 478 pupils were included into the study. The number of completed questionnaires returned was 465, a response rate of 97% while 13 (3%) questionnaires were incomplete. Overall, 76% (353/465) of pupils reported acne. 85% (300/353) students reported acne alone, and 15% (53/353) students reported acne and coexisting skin diseases. No skin problems reported by 24% (112/465) of the students and therefore, they did not complete the rest of the questionnaire. Only pupils who reported acne (353) were included into the data analysis.

Out of 353 pupils with acne, 227/353 (64%) were boys and 126/ 353 (36%) were girls. The largest number of participants with acne were 16 (37%) and 17 (26%) years old.

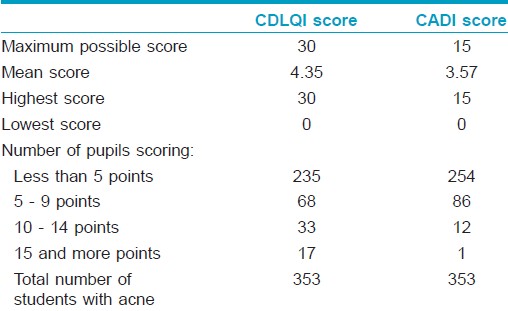

The overall mean CDLQI score (max 30) was 4.35 (14.7% impairment), range 0 - 30. 68 pupils scored between 5 and 9 points (17% - 30% impairment), 33 pupils scored between 10 and 14 points (33% - 47% impairment) and 17 pupils scored ≥ 15 points (≥ 50% impairment) [Table - 1].

The overall mean CADI score (max 15) was 3.57 (24% impairment), range 0 - 15. 86 pupils scored between 5 and 9 points (33% - 60% impairment), 12 pupils scored between 10 and 14 points (67% - 93% impairment) and 1 pupil scored the maximum 15 points (100% impairment) [Table - 1]. 11% of pupils scored highly across both questionnaires, 9% had moderate impairment of HRQoL and only 1 pupil had maximum scores in both questionnaires.

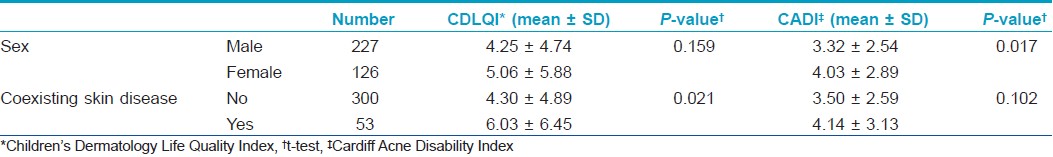

The overall mean of CDLQI and CADI scores were higher in girls than in boys, but the difference was statistically significant only for the CADI [Table - 2]. Children who had other associated skin diseases in comparison with those with acne only, scored higher in both questionnaires. However, a statistically significant difference in mean scores was found only for the CDLQI questionnaire [Table - 2].

23/227 boys (10%) and 23/126 girls (18%) were severely embarrassed, self-conscious, upset or sad due to their skin while 74/227 (33%) boys and 51/126 (40%) girls had mild emotion. 15% of pupils felt very depressed and miserable due to their acne. About 16% of pupils avoided swimming and other sports, and the same percent of adolescents experienced teasing or bullyng because of acne. Regarding going out, dancing, and having hobbies, acne had more negative impact on girls than on boys (10% of girls and 8% of boys avoided these activities). Acne-related sleep problems (very much and a lot) were reported by 6% of all pupils.

211/353 pupils (60%) affirmatively answered to the question of the CADI, which related to aggressiveness, frustration and embarrassment due to acne. About 3% of boys and 10% of girls avoided public changing rooms and wearing swimming costumes because of their acne all the time or most of the time. Acne was a major problem for 39/227 (17%) of affected boys and 23/126 (18%) of affected girls, and a minor problem for 62% of pupils.

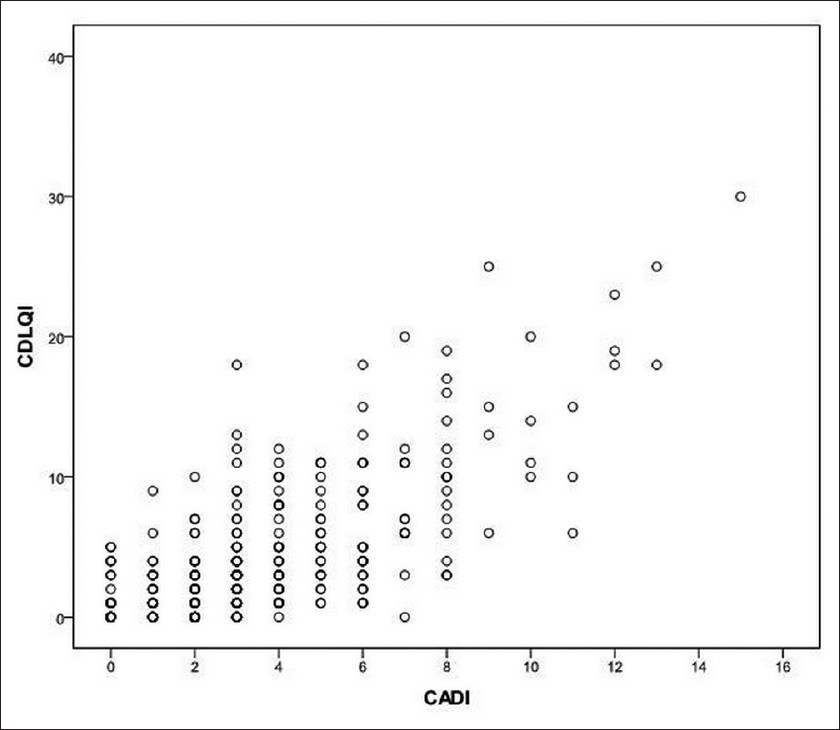

There was good correlation between the 2 questionnaires (Rho = 0.66), i.e., pupils who scored highly on the CDLQI also tended to score highly on the CADI [Figure - 1].

|

| Figure 1: Plot of the association between CDLQI and CADI (Spearman's Rho = 0.66). CDLQI - Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index, CADI - Cardiff Acne Disability Index |

Discussion

The prevalence of self-reported acne in this study (76%) is somewhat lower than in Scottish study [8] and higher than in Greek, [9] Japanese, [10] and Chinese study. [11] Although the comparison of prevalence between different studies is in general difficult because of differences in questionnaire design, settings and the population characteristics, our study confirms that acne is common in teenagers.

A higher proportion of Serbian males (64%) than females (36%) reported acne. Several other studies have shown the opposite findings. [9],[10],[12] The highest acne prevalence in our study was in those 16 (37%) and 17 (26%) years old, and these results are similar with the results obtained by other authors. [8],[10],[13]

In this cross-sectional study, the HRQoL of Serbian schoolchildren with acne was assessed for the first time using Serbian version of 2 questionnaires: The CDLQI (a generic questionnaire for children with skin disease) and the CADI (a disease-specific measure for acne). The study also provides a cross-validation of these 2 questionnaires.

Although the overall mean scores for both the CDLQI (4.35) and the CADI (3.57) are rather low, our study confirms that acne is associated with the impairment in HRQoL that is in line with previous studies performed among adolescents in other countries. [8],[14],[15] Relatively low scores may demonstrate the predominance of clinicaly mild acne in the community setting. However, the fact that all the pupils completed questionnaires together in the same classroom, with their peers being able to read their answers, may have prevented some of them to express how they really felt. For example, the total mean score of the CADI (7.57) found in Iranian adolescents with acne [15] was more than twice as higher as the mean of CADI score in our study.

The total CDLQI and CADI mean scores were higher in girls than in boys although statistically significant difference was found only for the CADI. This suggests that the psychological impact of acne may be greater for females than it is for males. A number of studies found that adolescent girls are more vulnerable than boys to the negative psychological effects of acne. [16],[17],[18]

The higher percentage impairment seen with the CADI (24%) than with the CDLQI (14.7%) among the same participants reflects the fact that CADI is an acne specific questionnaire, whereas the CDLQI is a generic dermatological questionnaire.

According to our results, the CADI question related to emotions, such as embarrassment, feeling upset or sad and self-consciousness scored significantly higher than the CDLQI question that also considers emotions (aggressiveness, frustration and embarrassment). This is in accordance with the findings of the Scottish study [8] Even more pupils in our study reported problems with emotions with the CADI than with the CDLQI questionnaire. On the other hand, some important issues such as, the aspects of treatment of acne are addressed only in CDLQI. This supports the suggestion to use both, the CDLQI and the CADI questionnaire in assessing HRQoL in patients with acne.

It is well-known that acne is associated with anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts. [1],[16],[19] In our study, 15% of pupils felt very depressed and miserable due to their acne. A cross-sectional study, conducted among 10,000 secondary school students in New Zealand, [20] found that acne was associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms, anxiety and suicide attempts, even after controlling for depressive symptoms and anxiety. A Turkish study [21] also reported that patients with acne were at increased risk for anxiety and depression compared to the normal population.

Acne also can substantially interfere with social and occupational functioning and result in impairment in quality of life. Most of pupils in our study did not consider that acne affected their social life and interpersonal relationships.

Pupils who had other skin disease associated with acne (15%) had higher scores in both questionnaires in comparison with the pupils affected by acne only (85%). However, statistically significant difference was found to exist only between mean values of overall scores for CDLQI, and not for the CADI questionnaire. Given that CDLQI is a generic questionnaire, some questions were not related to problems associated with having acne. Therefore, participants could score high on such questions (e.g. questions related to symptoms of coexisting skin disease) and contributed to the increase of the mean value of the overall score. On the other hand, CADI is an acne-specific questionnaire, not sensitive to detect symptoms of other skin diseases.

The strength of our study was a large number of adolescents surveyed from the general population, thus excluding the possibility of referal bias and overestimation of psychometric morbidity with hospital-based data.

The limitation of this cross-sectional study is that it may introduce biases associated with self-reporting such as recall bias, misclassification bias and under or over-reporting of information. The questionnaires used are suitable for the detection of psychosocial problems, but are not sufficient to diagnose depression or anxiety without clinical assessment.

Nevertheless, our study confirms a negative impact of acne on teenagers′ quality of life. Cross validation of the CDLQI and CADI has demonstrated good correlation between these 2 instruments. In addition, both scales were easy to administer.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Andrew Y Finlay, Department of Dermatology and Wound Healing, Cardiff University School of Medicine, Cardiff, UK, for the formal permission to translate and use CDLQI and CADI in this study. This study was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science, Serbia, Project No. 175025.

| 1. |

Dréno B. Assessing quality of life in patients with acne vulgaris: Implications for treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2006;7:99-106.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Levenson JL. Psychiatric issues in dermatology, part 3: Acne vulgaris and chronic idiopathic pruritus. Prim Psychiatry 2008;15:28-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Kokandi A. Evaluation of acne quality of life and clinical severity in acne female adults. Dermatol Res Pract [Internet]. 2010 Jul [Cited 2011 Jul 3]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2913789/pdf/DRP2010-410809.pdf.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Chia CY, Lane W, Chibnall J, Allen A, Siegfried E. Isotretinoin therapy and mood changes in adolescents with moderate to severe acne: A cohort study. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:557-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Rubinow DR, Peck GL, Squillace KM, Gantt GG. Reduced anxiety and depression in cystic acne patients after successful treatment with oral isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987; 17:25-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Section of Dermatology. School of Medicine, Cardiff University [Internet]. The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI). Serbian version. Translation information [cited 2011 October 15]. Available from: http://www.dermatology.org.uk/translationinfo/cdlqiSerbianinfo.html.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Section of Dermatology. School of Medicine, Cardiff University [Internet]. The Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). Serbian version. Translation information [cited 2011 October 15]. Available from: http://www.dermatology.org.uk/translationinfo/cadiserbianinfo.html.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Walker N, Lewis-Jones MS. Quality of life and acne in Scottish adolescent schoolchildrend: Use of the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) and the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:45-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Ifandi A, Efstathiou G, Georgala S, Chalkias J, et al. Coping with acne: Beliefs and perceptions in a sample of secondary school Greek pupils. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:806-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Kubota Y, Shirahige Y, Nakai K, Katsuura J, Moriue T, Yoneda K. Community-based epidemiological study of psychological effects of acne in Japanese adolescents. J Dermatol 2010; 37:617-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Yeung CK, Teo LH, Xiang LH, Chan HH. A community-based epidemiological study of acne vulgaris in Hong Kong adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol 2002;82:104-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Kilkenny M, Stathakis V, Hibbert ME, Patton G, Caust J, Bowes G. Acne in Victorian adolescents: Associations with age, gender, puberty and psychiatric symptoms. J Paediatr Child Health 1997;33:430-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Kilkenny M, Merlin K, Plunkett A, Marks R. The prevalence of common skin conditions in Australian school students: 3 Acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:840-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Pawin H, Chivot M, Beylot C, Faure M, Poli F, Revuz J, et al. Living with acne. A study of adolescents' personal experiences. Dermatology 2007;215:308-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Aghaei S, Mazharinia N, Jafari P, Abbasfard Z. The Persian version of the Cardiff Acne Disability Index. Reliability and validity study. Saudi Med J 2006;27:80-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Aktan S, Ozmen E, Sanli B. Anxiety, depression and nature of acne vulgaris in adolescents. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:354-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Kellett SC, Gawkrodger DJ. The psychological and emotional impact of acne and the effect of treatment with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:273-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Krowchuk DP, Stancin T, Keskinen R, Walker R, Bass J, Anglin TM. The psychosocial effects of acne on adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol 1991;8:332-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Picardi A, Mazzotti E, Pasquini P. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among patients with skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:420-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Purvis D, Robinson E, Merry S, Watson P. Acne, anxiety, depression and suicide in teenagers: A cross-sectional survey of New Zealand secondary school students. J Paediatr Child Health 2006;42:793-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Yazici K, Baz K, Yazici AE, Köktürk A, Tot S, Demirseren D, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2004;18:435-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,987

PDF downloads

1,993