Translate this page into:

Comparative study of efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in polymorphic light eruption: A randomized, double-blind, multicentric study

2 Department of Dermatology, Seth G S Medical College and King Edward VII Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India

3 Department of Dermatology, STD and Leprosy, Bangalore Medical College and Victoria Hospital, Bangalore, India

Correspondence Address:

Anil Pareek

Department of Medical Affairs and Clinical Research, Ipca Laboratories Ltd, 142 AB, Kandivli Industrial Estate, Charkop, Kandivli (West), Mumbai-400 067

India

| How to cite this article: Pareek A, Khopkar U, Sacchidanand S, Chandurkar N, Naik GS. Comparative study of efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in polymorphic light eruption: A randomized, double-blind, multicentric study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:18-22 |

Abstract

Background: Polymorphic light eruption is the most common photodermatosis characterized by nonscarring, pruritic, erythematous papules and plaques. Aim: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine in comparison with chloroquine in patients suffering from polymorphic light eruption. Methods: This was a randomized, double-blind, comparative, multicentric study conducted at two centers. This study enrolled 68 (58.1%) males, 49 (41.8%) females whose ages ranged from 18-73 years and average weight was 57.89 � 8.27 kg. A total of 117 patients were enrolled in the study. Out of 117 patients, 63 patients were randomized to receive hydroxychloroquine tablets 200 mg twice daily for the first month and 200 mg once daily for the next month. Similarly, 54 patients were randomized to receive chloroquine tablets 250 mg twice daily for the first month and 250 mg once daily for the next month. The total duration of therapy for both the study arms was two months. The severity and frequency of burning, itching, erythema and scaling were evaluated at predetermined intervals (at baseline, after four, eight and 12 weeks of therapy). Results: A significant reduction in severity scores for burning, itching, and erythema was observed in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine than with chloroquine ( P < 0.05). However, hydroxychloroquine was as good as chloroquine in reducing severity of scaling at the end of the study evaluation ( P = 0.229). The good to excellent response was reported by 68.9% of the patients who received hydroxychloroquine and by 63% of the patients who received chloroquine. The adverse events reported were mild to moderate and none of the patients reported any serious adverse events or ocular toxicity in this study. Conclusion: Hydroxychloroquine was found to be significantly more effective than chloroquine in the treatment of polymorphic light eruption and can be used safely in the dosage studied in such patients with little risk of ocular toxicity.

|

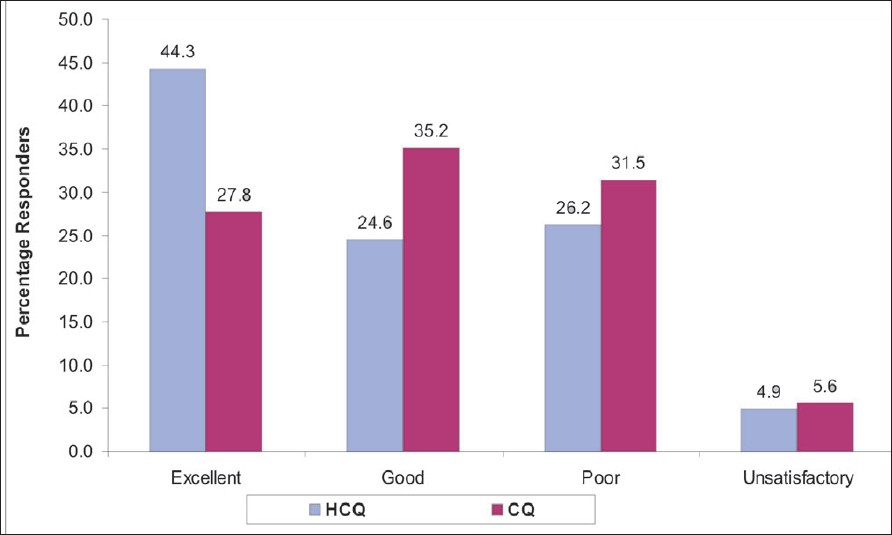

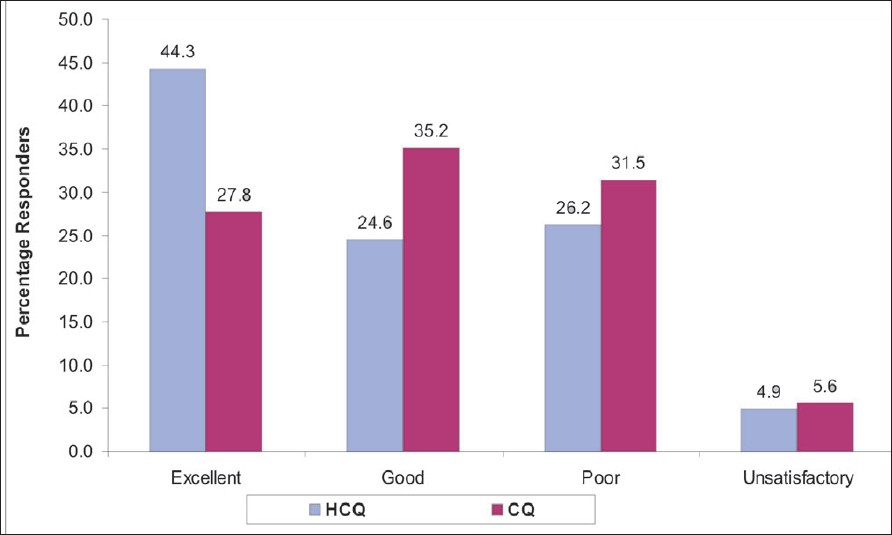

| Figure 2: Percentage responders in both treatment arms HCQ (n = 61), CQ (n = 54). |

|

| Figure 2: Percentage responders in both treatment arms HCQ (n = 61), CQ (n = 54). |

|

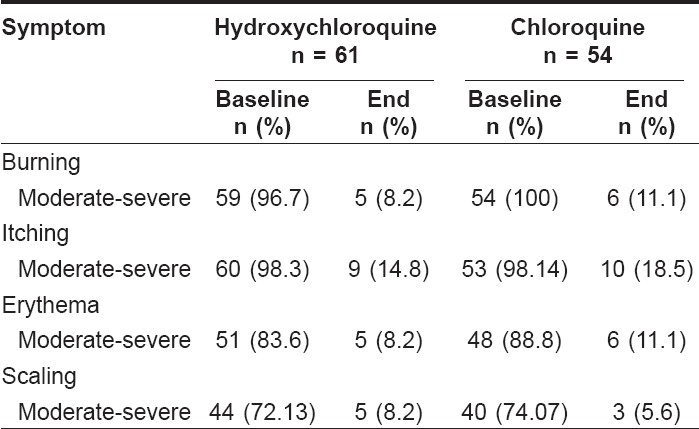

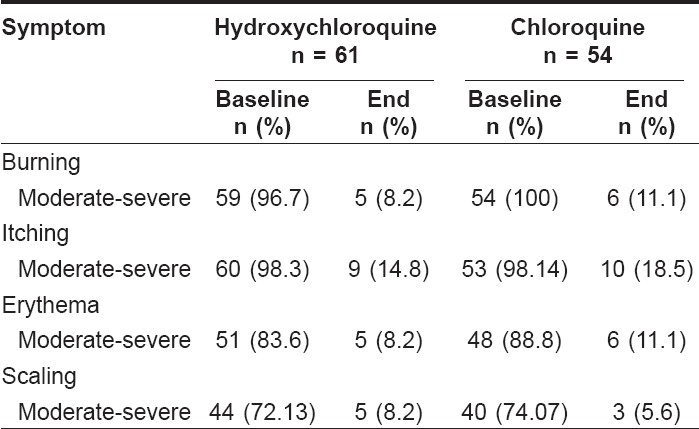

| Figure 1: Percentage distribution of patients based on the severity of symptoms before and after therapy in both treatment arms HCQ - hydroxycholorquine, CQ - chloroquine, BB - burning baseline, BE - burning end, IB - itching baseline, IE - itching end, EB - erythema baseline, EE - erythema end, SB - scaling baseline, SE - scaling end. |

|

| Figure 1: Percentage distribution of patients based on the severity of symptoms before and after therapy in both treatment arms HCQ - hydroxycholorquine, CQ - chloroquine, BB - burning baseline, BE - burning end, IB - itching baseline, IE - itching end, EB - erythema baseline, EE - erythema end, SB - scaling baseline, SE - scaling end. |

Introduction

Polymorphic light eruption (PLE), first described in 1817 by Robert Willan, is the most common of idiopathic photodermatoses. [1] It is an acquired disorder characterized as an intermittent, transient, delayed response after ultraviolet (UV) light exposure that results in an abnormal cutaneous response. The cutaneous response has been described as nonscarring, pruritic, erythematous papules, vesicles or plaques on light-exposed skin. [2],[3],[4] Other presentations include vesiculobullous, hemorrhagic, erythema multiforme-like and insect bite-like in appearance.

For the majority of patients with PLE, the rash is mild and self-limiting and quickly settles within a few days of sun avoidance. The proportion of people with PLE who seek medical attention is estimated to be less than 26%, although this still represents a large proportion of patient population. Treatment may be prophylactic or suppressive and depends on the severity of the disease and the patient′s choice. [5]

Topical sunscreens have been the mainstay of treatment for PLE. However, many patients remain seriously inconvenienced because the condition is frequently not controlled. Psoralen photochemotherapy (PUVA) [6],[7] and ultraviolet (UV-B) radiation therapy that were introduced as prophylactic treatments are not always suitable or effective. Another therapy, 4-aminoquinolone-chloroquine, has been used with some apparent efficacy but its tendency to cause cumulative ocular toxicity is its major drawback. [8] Hydroxychloroquine sulfate (HCQS) however, may be less oculotoxic and more suitable for repeated treatment. The preventive efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in PLE has been demonstrated in a placebo-controlled trial showing reduction in eruption. [9] Short-term treatment courses with hydroxychloroquine seem to be well-tolerated with minimized risk of ocular lesions. [9],[10]

The objective of the present study is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine in comparison with chloroquine in patients with polymorphic light eruption.

Methods

This was a randomized, double blind, comparative study conducted at the Dermatology departments of Seth G. S. Medical College and King Edward VII Memorial Hospital, Mumbai and at the Bangalore Medical College and Victoria Hospital, Bangalore. Male and female patients, ≥ 18 years who were willing to give informed consent and who agreed for regular follow-up were included in the study. As photo-testing facilities were not available, the diagnosis of PLE was done based on taking detailed medical history and the presence of clinical signs and symptoms that included the presence of itchy, erythematous papules or plaques on sun-exposed areas. Medical history was taken to rule out all external (topical) or internal (drugs) photosensitizing causes. Patients with a history of allergy to pollens or plants were also excluded. Morphologies that were taken as compatible with PLE were micropapules, papules and plaques. Patients with morphology suggestive of phototoxicity or photoallergy were also excluded. Skin biopsy was done in diagnostically difficult cases to confirm the diagnosis of PLE and to rule out photoallergic dermatitis. The presence of spongiosis was taken as a histopathologic parameter for the diagnosis of photoallergic dermatitis. Patients who had a history of hypersensitivity to chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine or any other related drug or with previous history of other adverse effects with the study drugs were excluded from the study. Patients showing any significant clinical or laboratory abnormality such as abnormal liver or kidney function or with retinal or visual field changes noted during the screening visit were excluded from the study. Patients who were receiving cardioactive therapy, pregnant or lactating women and female patients with abnormal amenorrhea were not recruited in this study. All eligible patients provided their informed consent prior to participating in this study. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committees of each of the participating centers.

A total of 117 patients eligible for the study were randomized in two treatment arms. The patients were randomized using computer-generated randomization codes. The first group received hydroxychloroquine tablets 200 mg twice daily for the first month and 200 mg once daily for the next month. Similarly, the second group received chloroquine tablets 250 mg twice daily for the first month and 250 mg once daily thereafter for the next month. The total duration of therapy for both study treatments was two months. The patients were followed up one month after completion of therapy. To ensure that the study was blinded, both the drugs were formulated as tablets of the same color, size and shape. The total number of tablets to be administered for the entire duration of therapy to each patient was also similar for both the treatment arms. No other concomitant medicine (including sunscreens) that could impact the skin lesions were allowed. However, patients were advised to avoid sunlight as much as possible.

Efficacy was assessed in those patients who had received at least one month of therapy with either drug. Severity of burning, itching, erythema and scaling were evaluated at predetermined intervals (at baseline, after four, eight and 12 weeks of therapy). Severity was evaluated using a 3-point scale. Severity was graded as 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate and 3 = severe. Based on these scores, a subjective response was reported by the investigators as excellent (complete resolution of all symptoms), good (if there was resolution of more than two symptoms), poor (if there was a fall in baseline symptom scores with or without resolution of symptoms and if the patient could not be categorized as an excellent or good responder) and unsatisfactory (if there was no change or worsening of signs and symptoms as compared to the baseline).

Any patient who had received at least one dose of the study medication was evaluated for safety. The adverse signs and symptoms reported by the patients were recorded in the case record forms. The incidence, severity and causal relationship of the adverse events to the study medication were reported in the case record forms. Also, all the laboratory evaluations like complete blood count (CBC) and blood biochemistry were repeated at the end of 12 weeks to assess any significant changes in laboratory parameters due to the study drugs. For comparing the efficacy of these treatments, statistical Wilcoxon signed rank test was used and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

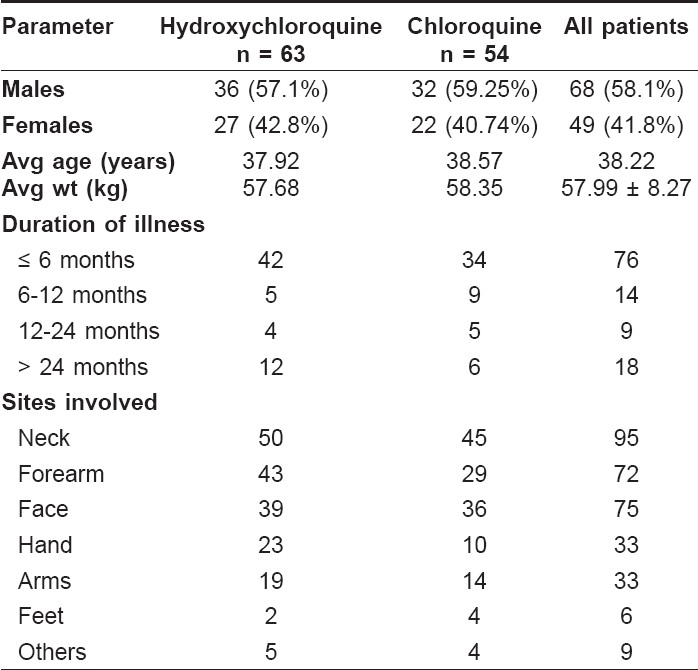

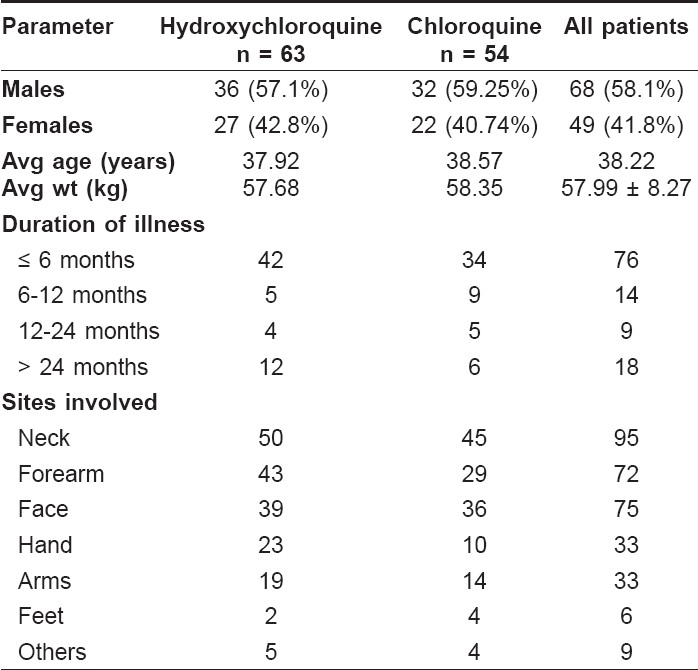

A total of 117 patients were studied, of whom, 63 received hydroxychloroquine and 54 patients received chloroquine. Out of the 63 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine, 61 patients completed the trial. One patient was lost to follow-up and one patient was withdrawn from the study as a result of protocol violation. This study recruited 68 (58.1%) males and 49 (41.9%) females in the age range of 18 to 73 years with an average weight of 57.89 ± 8.27 kg. The baseline demography of two treatment groups reported no significant difference [Table - 1]. The commonly involved sites for PLE were the neck, forearm, face, hands and arms.

Efficacy evaluation

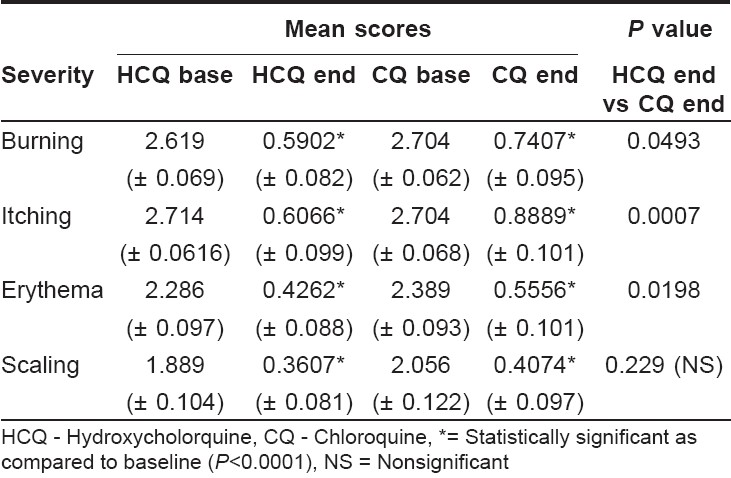

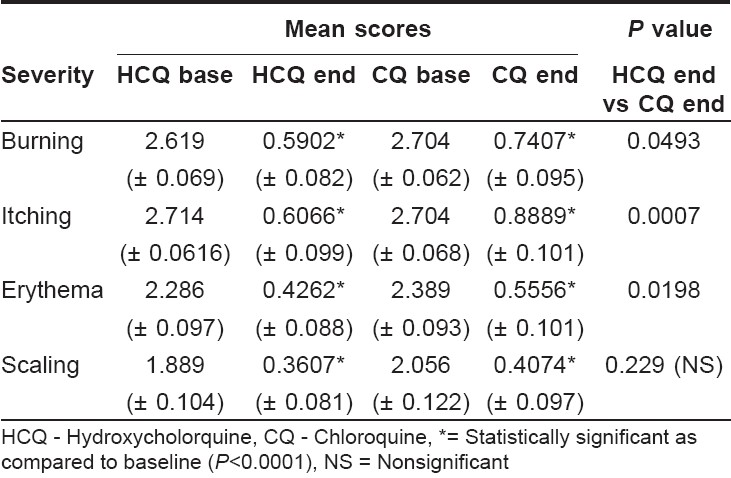

The efficacy of the individual treatment was evaluated at the end of 12 weeks for changes in severity of burning, itching, scaling and erythema from the baseline. Statistical analysis using the Wilcoxon signed rank test reported significant ( P < 0.0001) decreases in severity of burning, itching, erythema and scaling for both the treatment arms at the end of 12 weeks [Table - 2]. A greater number of patients in the chloroquine group reported moderate to severe burning, itching and erythema at the end of 12 weeks than in the hydroxychloroquine group. However, moderate to severe scaling was reported to a greater extent in the hydroxychloroquine group than in the chloroquine group. [Table - 3] and [Figure - 1] show the percentage distribution of patients before and after therapy in both treatment arms.

The two treatments were compared for their severity of symptoms at the end of 12 weeks using the Wilcoxon signed ranked test for difference in their efficacy. The reduction in severity scores for burning, itching and erythema was significantly more in the hydroxychloroquine group as compared to the chloroquine group ( P < 0.05). However, chloroquine was as good as hydroxychloroquine in reducing scaling severity ( P = 0.229).

The complete resolution of all the symptoms was reported by 27 (44.3%) patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and by 15 (27.8%) patients treated with chloroquine. There were 15 (24.6%) patients who reported complete resolution of two or more than two symptoms in the hydroxychloroquine group and 19 (35.2%) patients in the chloroquine group. Hence, good to excellent responses were reported by 68.9% of the patients who received hydroxychloroquine and by 63% of the patients who received chloroquine. There were more poor responders on chloroquine therapy than on hydroxychloroquine (31.5 vs 26.2% on chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine respectively). Three patients responded unsatisfactorily in both treatment groups. These patients reported no change in the signs and symptoms scores from the baseline [Figure - 2].

Safety Evaluation

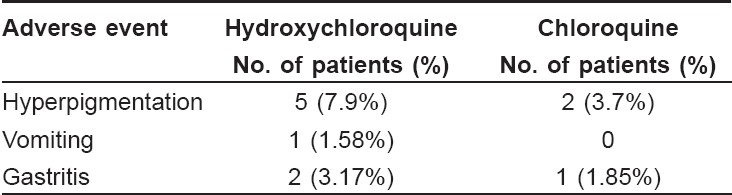

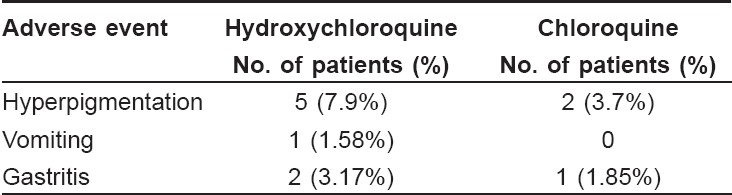

Safety evaluation data [Table - 4] was available for all the patients who participated in the study. Overall, 11 patients reported adverse events during this study. None of the patients reported any serious adverse events. Eight patients in the hydroxychloroquine group and three patients in the chloroquine group reported adverse events. These events were of mild to moderate intensity and subsided on their own. No patients reported any changes in vision or ocular disturbances. The two treatment groups did not report any clinically significant changes in laboratory parameters like erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), serum bilirubin, random blood sugar and serum creatinine.

Discussion

Polymorphic light eruption is a highly prevalent photosensitivity disorder, estimated to affect 11-21% of the population in temperate countries. [11] It is more common in females and the etiology is uncertain although there is some evidence of an immune basis. It is thought to be caused by an immune reaction to a compound in the skin, which is altered by exposure to ultraviolet radiation, [12],[13] resulting in an inflammatory rash. It is usually provoked not only by short wavelength UV-B but also by longer wavelength UV-A. There are wide-ranging treatments reported for this very common and sometimes disabling photosensitivity condition, indicating the challenges of its treatment. Although phototherapy with or without the coadministration of corticosteroids is widely used in PLE, [14] some patients require other treatment modalities. The antimalarial drugs - chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, have shown efficacy in the treatment of PLE. Chloroquine however, has shown an unacceptable risk of ocular toxicity that is believed to be a result of its affinity for melanin. Comparative studies have reported that hydroxychloroquine has a significantly lower risk of causing ocular toxicity than chloroquine. [15]

The efficacy of hydroxychloroquine was evaluated in a four months long, randomized, placebo-controlled study. The researchers of this study found that oral hydroxychloroquine significantly reduced the presence of rash in PLE patients as compared to the placebo and was tolerated well by all the patients treated with this drug. [9]

The present study is the first randomized, double blind comparison of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in patients with polymorphic light eruption. The patient population in this study was uniformly distributed with respected to age, sex, body weight and sites involved. The majority of patients on this study were suffering from PLE for less than or equal to six months. Patients received either hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for eight weeks and were evaluated after 12 weeks for efficacy.

Consistent with literature reports, [16] the results of our study also confirmed that both the drugs are effective in reducing the severity of the signs and symptoms of polymorphic light eruption. A greater number of patients treated with hydroxychloroquine reported complete resolution of all signs and symptoms of PLE as compared to patients treated with chloroquine [27 (44.3%) vs 15 (27.8%)] in our study. The adverse events reported in our study were similar to those reported in literature. [17] Both the drugs were well-tolerated by all patients and no patient discontinued the medication due to adverse events. None of the patients reported any ocular toxicity with hydroxychloroquine in our study confirming its ocular safety as reported in literature. [18]

Hence, hydroxychloroquine was well-tolerated with a superior quality of response as compared to chloroquine. Thus, hydroxychloroquine turns out to be a better option for treating PLE and can be used much more frequently and freely than chloroquine as chloroquine is more likely to cause irreversible retinal damage. [19]

Acknowledgment

This study was sponsored by Ipca Laboratories Ltd., Mumbai, India. The authors thank Dr. Priyam Kembre for her help in performing this research. The authors also thank Dr. Sanket Jadhav for his assistance in statistical analysis of the data and Mr. Santosh Patil for providing technical assistance for publishing this research work

| 1. |

Ferguson J, Ibbotson SH. The idiopathic photodermatoses. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1999;18:257-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Epstein JH. Polymorphous light eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol 1980;3:329-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Nynberg F, Hasan T, Puska P, Stephansson E, Hδkkinen M, Ranki A, et al . Occurrence of polymorphous light eruptions in lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1997;136:217-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Tutrone WD, Spann CT, Scheinfeld N, Deleo VA. Polymorphic light eruption. Dermatol Ther 2003;16:28-39.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Ling TC, Gibbs NK, Rhodes LE. Treatment of polymorphic light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2003:19:217-27.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Murphy GM, Logan RA, Lovell CR, Morris RW, Hawk JL, Magnus IA. Prophylactic PUVA and UVB therapy in polymorphic light eruption--a controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 1987;116:531-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Bilsland D, George SA, Gibbs NK, Aitchison T, Johnson BE, Ferguson J. Comparison of narrow band phototherapy (TL-01) and photochemotherapy (PUVA) in the management of polymorphic light eruption. Br J Dermatol 1993;129:708-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Corbett MF, Hawk JLM, Herxheimer A, Magnus IA. Controlled therapeutic trials in polymorphic light eruption. Br J Dermatol 1982;107:571-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Murphy GM, Hawk JL, Magnus IA. Hydroxychloroquine in Polymorphic light eruption: A controlled trial with drug and visual sensitivity monitoring. J Dermatol 1987;116:379-86.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Tobin DR. Hydroxychloroquine in light eruption: New indication. Prescrire Int 1999;8:72-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Holzle E, Plewig G, von Kries R, Lehmann P. Polymorphous light eruption. J Invest Dermatol 1987;88:32s-8s.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Jansen CT. The morphologic features of polymorphous light eruptions. Cutis 1980;26:164-7,169-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Epstein JH. Polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 1997;13:89-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Patel DC, Bellaney GJ, Seed PT, McGregor JM, Hawk JL. Efficacy of short-course oral prednisolone in polymorphic light eruption: A randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 2000;143:828-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Jones SK. Ocular toxicity and hydroxychloroquine: Guidelines for screening. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:3-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Murphy GM, Hawk JL, Magnus IA. Hydroxychloroquine in Polymorphic light eruption: A controlled trial with drug and visual sensitivity monitoring. Br J Dermatol 1983;109:37.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Breckenridge A. Risks and benefits of prophylactic antimalarial drugs. BMJ 1989;299:1057-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Rynes RI, Krohel G, Falbo A, Reinecke RD, Wolfe B, Bartholomew LE. Ophthalmologic safety of long-term hydroxychloroquine treatment. Arthritis Rheum 1979;22:832-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Finbloom DS, Silver K, Newsome DA, Gunkel R. Comparison of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine use and the development of retinal toxicity. J Rheumatol 1985;12:692-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,722

PDF downloads

4,360