Translate this page into:

Rhinoentomophthoromycosis

2 Department of Microbiology, Dr. S. M. C. S. I. Medical College and Hospital, Karakonam, Trivandrum, Kerala, India

3 Department of ENT, Dr. S. M. C. S. I. Medical College and Hospital, Karakonam, Trivandrum, Kerala, India

Correspondence Address:

Mathew M Thomas

Department of Dermatology, Dr. S. M. C. S. I. Medical College, Karakonam, Trivandrum, Kerala - 695504

India

| How to cite this article: Thomas MM, Bai SM, Jayaprakash C, Jose P, Ebenezer R. Rhinoentomophthoromycosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:296-299 |

Abstract

A sixty year old patient presented with a slowly progressive swelling of the nose, of one year duration, suggesting a clinical diagnosis of subcutaneous zygomycosis. On investigation, the tissue fungal culture grew Conidiobolus coronatus , confirming the diagnosis as rhinoentomophthoromycosis. He was treated with a combination of oral fluconazole and oral potassium iodide for a total period of 5 months. His symptoms subsided completely. Serial CT scanning of paranasal sinuses showed the gradual resolution of the swelling, in response to the treatment. Early detection of the disease and combination therapy gave rapid and good results. This is the first case of its kind to be reported from Kerala, the southern state of India. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction

Rhinoentomophthoromycosis (conidiobolomycosis) is a rare, chronic, localized, subcutaneous zygomycosis, characterized by painless, woody swelling of the rhinofacial region.[1] The disease occurs mainly in the tropical rain forests of Africa, South and Central America and South-East Asia. A few cases have been reported from India. We report a case of this rare subcutaneous zygomycosis.

Case report

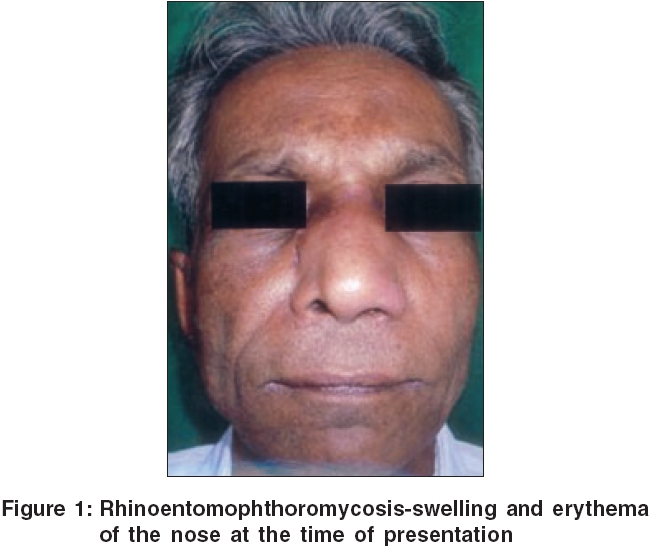

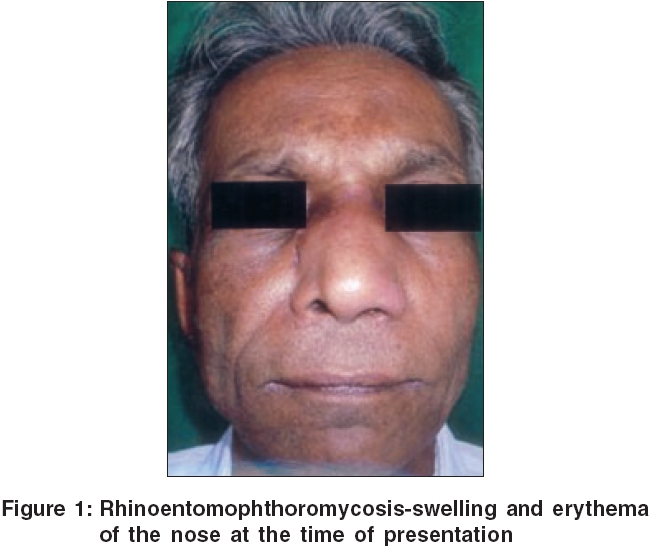

A 60 year old retired teacher and agriculturist presented to us with a slowly progressive swelling of the nose, and nasal block of 1 year duration. He was treated earlier with various antibiotics, with no improvement. Even though he was a known asthmatic, he was not on steroids. He was also not a diabetic. General and systemic examinations were unremarkable, except for a disfigured facial appearance. Local examination revealed a mildly tender, dull, erythematous, woody hard, uniform, smooth, non-pitting swelling on the root of the nose, extending to the left cheek [Figure - 1]. The overlying skin was intact, and a finger could be insinuated beneath the swelling. There was no regional lymph node enlargement. Anterior rhinoscopy showed hypertrophied inferior turbinate on the left side. Based on these features, a clinical impression of subcutaneous zygomycosis was made.

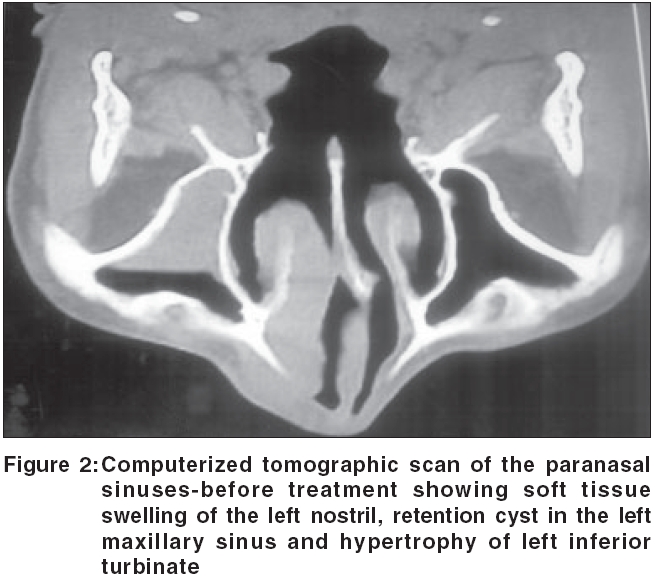

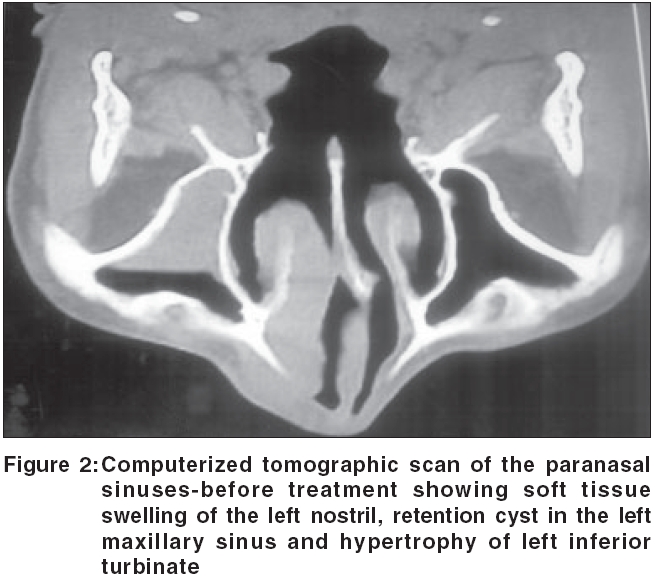

Routine blood examination was normal. X-ray of paranasal sinuses showed features of frontal and maxillary sinusitis. Plain CT scan of the paranasal sinuses showed soft tissue swelling of nose on the left side, a retention cyst in left maxillary sinus, and hypertrophy of left inferior turbinate [Figure - 2]. Incision biopsy sent from the lesion showed only chronic inflammatory changes. PAS staining was negative for fungi.

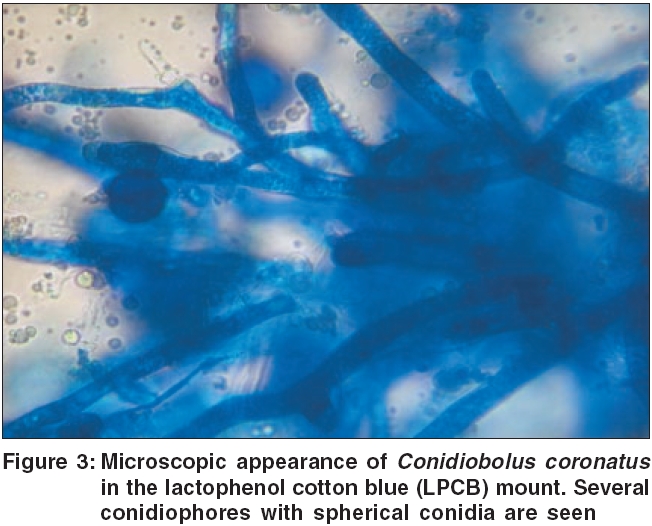

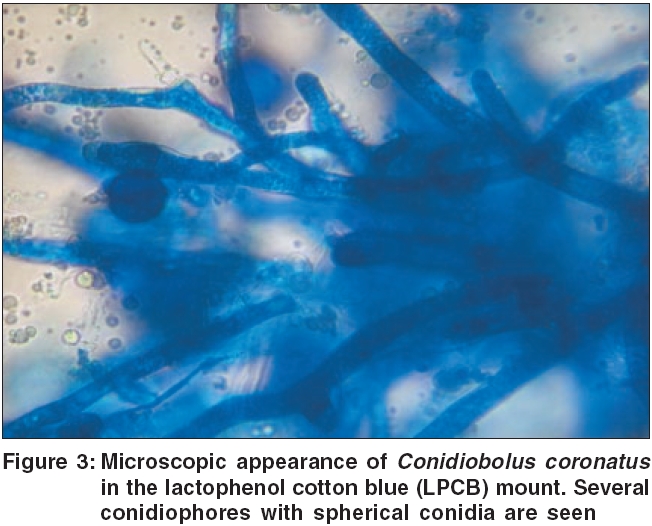

The biopsied tissue was sent for potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal culture. Broad thin walled non-septate mycelia were found in the KOH preparation. In the Sabouraud′s dextrose agar medium, rapidly growing flat cream-colored and glabrous colonies were grown. The sides of the culture tube soon became covered with conidia. Lactophenol cotton blue (LPCB) mount showed several conidiophores, and terminal spherical conidia with villi [Figure - 3]. Based on these features, the fungus was identified as Conidiobolus coronatus . A final diagnosis of Rhinoentomophthoromycosis was made.

The patient was treated with freshly prepared oral potassium iodide in a concentration of 1 gm/ml (i.e., 1 drop = 67 mg). Oral potassium iodide was started with 5 drops t.i.d., and increased by 3 drops every 3 days, upto a maximum of 15 drops t.i.d. After the patient became symptomless, this was gradually tapered to a maintenance dose of 5 drops t.i.d. Oral fluconazole 200 mg daily was also given, which was stopped after 1 month due to severe nausea, whereas oral potassium iodide was continued. Before and during treatment, the patient′s thyroid function test, SGPT, and serum potassium were monitored and were found to be unaltered. At two months of treatment, nasal swelling and nasal block disappeared, and the patient regained his normal facial appearance.

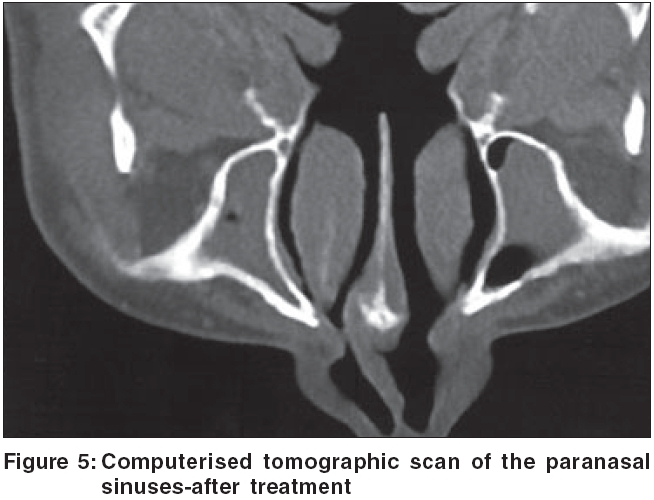

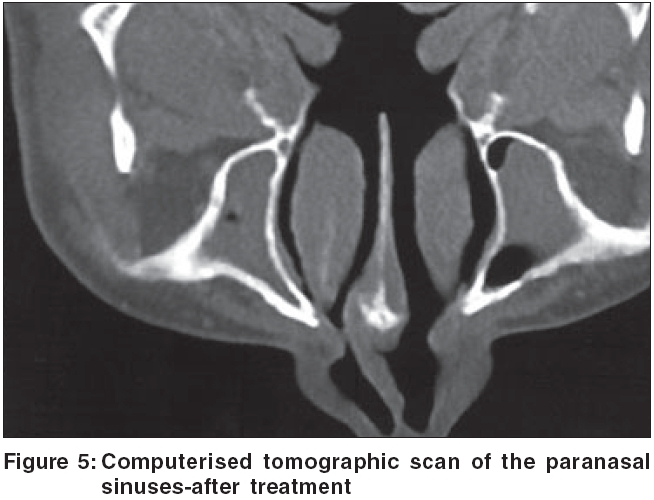

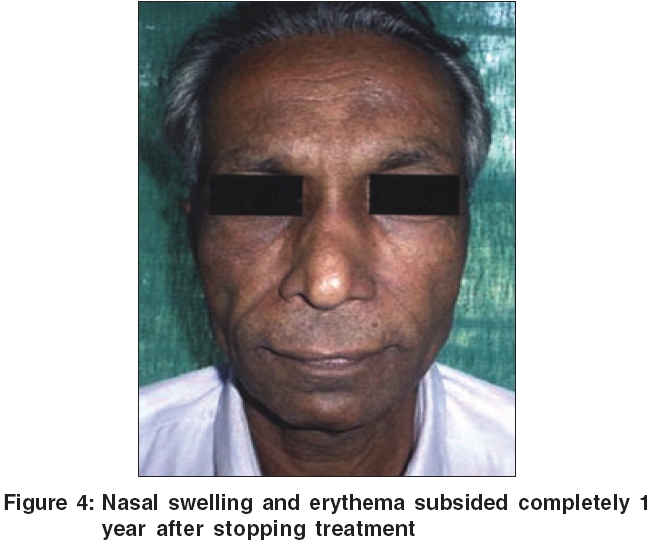

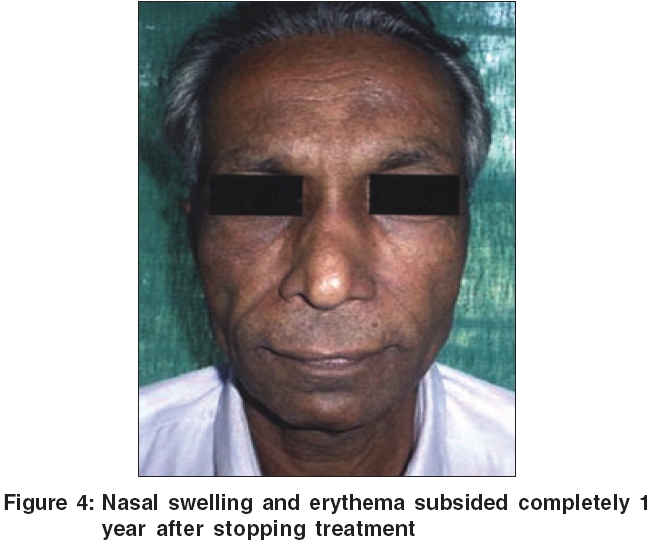

Repeat CT scan of para nasal sinuses (PNS) done at 2 months and 5 months of treatment showed the serial resolution of the swelling [Figure - 5]. A nasal endoscopy at 5 months was normal. A repeat tissue fungal culture from the left inferior turbinate and adjacent nasal mucosa, did not show any growth. Hence, oral potassium iodide was stopped (total treatment duration-5 months). The patient is under follow up, and is asymptomatic since 1 year [Figure - 4].

Discussion

Rhinoentomophthoromycosis (conidiobolomycosis) is a rare, chronic, localized, subcutaneous zygomycosis, characterized by painless, woody swelling of the rhinofacial region.[1] It causes severe facial disfigurement (like that of a hippopotamus).[2] It occurs mainly in the tropical rain forests of Africa, South and Central America, and South-East Asia. A few cases have been reported from India. Adult males are more affected. It usually begins in the inferior turbinate, and spreads in the submucosa through the natural ostia to the paranasal sinus, and to the subcutaneous tissue of the face (forehead, periorbital region and upper lip).[3] Nasal polyposis and nasal granulomas can occur. As a rule, the lesions are firmly attached to the underlying tissue, although the bone is spared. Overlying skin remains intact. Spread to the lymph nodes has been reported. The smooth rounded edge of the swelling can be demarcated by insinuating a finger underneath it. The condition is slowly progressive, but seldom life- threatening. The most common symptom is a unilateral nasal obstruction.

This fungal infection is caused by Conidiobolus coronatus (Entomophthora coronata), a mould belonging to the order Entomophthorales of the class Zygomycetes . It was first isolated in 1897, and the first human case with substantiative mycologic evidence was reported by Bras et al in 1965.[4] The fungus lives as a saprophyte in soil humus and on decomposing plant matter in moist, warm climates.[5] It can also parasitize certain insects and frogs. Infection is acquired through inhalation of spores, or their introduction into the nasal cavities by soiled hands. Most cases affect men with agricultural or outdoor occupations. The reason of its rarity in Kerala, may be due to the lesser percentage of agriculturists here, as compared to other parts of India.

Even if the diagnosis is obvious from the clinical appearance, mycological and histological examinations are essential for confirmation. Potassium hydroxide preparation of the nasal smear, or biopsy tissue from the lesion reveals broad, nonseptate, thin-walled mycelial filaments. In Sabouraud′s dextrose agar (SDA) medium, colonies of Conidiobolus coronatus grow rapidly. Histopathological features of the biopsy specimen include fibroblastic proliferation, chronic granulomatous inflammatory reaction, and broad thin walled hyphae.[6] The Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon (hyphal elements, in the tissue being surrounded by an eosinophilic sleeve) may be seen. Periodic acid-schiff′s (PAS) stain is useful to demonstrate the fungal hyphae.

Treatment of rhinoentomophthoromycosis is difficult because the diagnosis is usually established late, but patients often respond to oral itraconazole (200 to 400 mg/day), ketoconazole (200 to 400 mg/day), fluconazole (100-200 mg/day), amphotericin-B, and cotrimoxazole.[7] Of these, itraconazole and fluconazole are both effective and relatively safe.[8] Treatment should be continued for at least 1 month after the lesions have cleared. Saturated potassium iodide solution (1 gm/ml) is useful for patients in developing countries, because of its ease of administration and low cost. It is initiated in a dose of 5 drops/day (diluted in water, milk or fruit juice), and gradually increased upto a maximum of 40-50 drops per day, as tolerated.[9] The exact mechanism of its action is not known. Iododerma, acneiform eruption, gastric intolerance, increased salivation and lacrimation, unpleasant brassy taste, hypothyroidism etc. are the usual side effects. Combination therapy with oral potassium iodide and oral azoles, give rapid and lasting results. Surgical resection is seldom helpful and it may hasten the spread of infection. Cryotherapy has been tried with little success. Relapse is common, even after successful treatment. Differential diagnosis of Rhinoentomophthoromycosis includes cellulitis, rhinoscleroma, lymphoma, lymphoedema, and sarcoma.

It is noteworthy that only less than 10 cases of rhinoentomophthoromycosis from India are reported in the literature.[10],[11],[12] Most of these cases were accidentally detected, either from a surgical biopsy or FNAC. To the best of our knowledge, our case is the first of its kind to be reported from Kerala, the southern most state of India.

Acknowledgments

The Director, Dr. Bennet Abraham, and the Principal Dr. Glorine Gnanathankom, Dr. S. M. C. S. I. Medical College, Karakonam, Trivandrum Dist, Kerala, India, for providing necessary facilities in the departments of Dermatology and Microbiology, Medical Education Unit of Dr. S. M. C. S. I. Medical College, Karakonam, Trivandrum Dist, Kerala, India.

| 1. |

Richardson MD, Warnock DW. Entomophromycosis. In: Richardson MD, Warnock DW, editor. Fungal infection. Diagnosis and Management. 3rd ed. UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. p. 293-7 .

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Testa J, Vuillecard E, Ravisse P, Dupont B, Gonzalez JP, Georges AJ. 2 new cases of rhinoentomophthoromycosis diagnosed in the Central African Republic (review of the literature) Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales 1987;80:781-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Ochoa LF, Duque CS, Velez A. Rhinoentomophthoromycosis- Report of two cases. J Laryngol Otol 1996;110:1154-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Bras G, Gordon CC, Emmons CW, Prendegast KM, Sugar M. A case of phycomycosis observed in Jamaica; Infection with Entomophthora Coronata. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1965;14:141-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Hay RJ. Moore M. Mycology. In: Champion RH, Burton JI, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, editors. Rook/Wilkinson/Ebling Textbook of Dermatology. 6th ed. London: Blackwell Science Limited: 1998. p. 1277-376.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Richardson MD, Pirkko KK, Gillian SS. Rhizopus. Rhizomucor, absidia and other agents of systemic and subcutaneous zygomycoses. In: Patrick RM, Ellen JB, et al . editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology Vol. 2, 8th ed., ASM Press; 2003. p. 1761-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical Mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:91-102.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Valle AC, Wanke B, Lazera MS, Monteiro PC, Viegas ML. Entomophthoromycosis by Conidiobolus coronatus. Report of a case successfully treated with the combination of itraconazole and fluconazole. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2001;43:233-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Loreetta SD. Newer uses of older drugs: An update. In: Stephen EW. Comprehensive dermatologic drug therapy 1st ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2001. p. 426-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Mukhopadhyay D, Ghosh LM, Thammayya A, Sanyal M. Entomophthoromycosis caused by Conidiobolus coronatus: Clinicomycological study of a case. Auris Nasus Larynx 1995;22:139-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Pai MR, Kini H, Kini US. Rhinoentomophthoromycosis: A report of three cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 1993;36:65-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Singh D, Kochhar RC, Seth HN. Rhinoentomophthoromycosis. J Laryngol Otol 1976:90:871-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

6,271

PDF downloads

1,501