Translate this page into:

Clinical efficacy and safety profile of handheld narrow band ultraviolet B device therapy in vitiligo – Systematic review and meta-analysis

Corresponding author: Dr. Suvesh Singh, Department of Dermatology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. Email id: suveshsingh2658@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Khandpur S, Singh S, Paul D. Clinical efficacy and safety profile of handheld narrow band ultraviolet B device therapy in vitiligo – Systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2025;91:321-31. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_71_2024

Abstract

Background

Handheld narrowband ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) device is a portable, home-based, patient-friendly equipment used in vitiligo. It is a newer promising treatment that lacks generalised consensus due to heterogenicity among studies.

Objective

To determine the clinical efficacy and safety profile of handheld NB-UVB devices in the treatment of vitiligo.

Methods

Following the PRISMA guidelines and using appropriate keywords, the Embase, PubMed and Scopus databases were searched on 28 November 2023. Data on the proportion of patients with a percentage of re-pigmentation and toxicity were extracted from the included studies. Random effects and fixed model were utilised to generate pooled estimates via meta-analysis.

Results

Out of 250 articles, 13 studies (557 patients) were included. The extent of repigmentation achieved over a median duration of 6 months (range 3-12 months) was quantified to be > 25%, > 50%, and >75 % in 63.6% (95% CI: 51.0–75.3%), 40.8% (95% CI: 30.4–51.6%) and 15.4% (95% CI: 7.6–25.3%) of patients respectively. After 12 weeks of treatment, the proportions of patients achieving > 25%, > 50%, and >75% re-pigmentation were 31.1% (95% CI: 9.6–58.3%), 12.9% (95% CI: 3.1–28.1%) and 6.5% (95% CI: 1.7–14.1%), respectively. Similarly, at 24 weeks, these proportions were 53.2% (95% CI: 24.5–80.7%), 36.7% (95% CI: 15.8–60.5%), and 11.1% (95% CI: 2.9–23.7%). Minimal erythema dose (MED) calculation-based therapy was not significantly better than therapy given without MED calculation (p = 0.43). The studies with only stable vitiligo patients did not achieve significantly greater > 25% (p = 0.06), > 50% (p = 0.80), and > 75% (p = 0.25) re-pigmentation compared to the studies that also included active or slowly progressive vitiligo. Three sessions per week resulted in significantly higher > 50% (p < 0.01) and > 75% (p = 0.01) re-pigmentation. Totally, 11.3% (38/334) of patients showed no response to therapy. The most commonly reported adverse event was erythema in 33.4% (95% CI: 19.3–49.2%) of patients, with grade 3 and 4 erythema in 27 and 15 patients, respectively. Other adverse events included pruritus, burning, hyperpigmentation, dryness, and blister formation observed in 22.1%, 16.4%, 19.1%, 9.8%, and 9.7% of patients, respectively.

Conclusion

Handheld NB-UVB portable home-based devices are an efficacious and safe treatment option in vitiligo patients even without MED calculation, when the treatment frequency is three to four sessions per week.

Keywords

Narrow band ultraviolet B

NB-UVB

handheld

vitiligo

Introduction

Vitiligo is a common acquired depigmentary disorder of the skin, affecting 0.5–2% of the general population.1 Individuals with vitiligo experience diminished quality of life (QoL), social isolation, psychological distress, and reduced self-esteem.2 Despite various non-surgical and surgical therapies, phototherapy still remains the first-line and standard therapy for vitiligo. In vitiligo, NB-UVB therapy (311 ± 2 nm) carries a distinct advantage over the psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy.3 There are various proposed mechanisms by which NB-UVB therapy produces re-pigmentation.4,5

The standard protocol for NB-UVB in vitiligo consists of three sessions per week on alternate days, with the initial treatment time determined by the skin phototype or MED and dose escalation, depending on the patients’ response to treatment and the occurrence of side effects.6 Among an array of phototherapy units, handheld NB-UVB portable home-based devices have been shown to have an important role in the treatment of vitiligo.7 Such devices consist of a plastic case containing TL-9W/01NB-UVB lamps that emit a wavelength of 310–315 nm (peak 311) uniformly over a specific area at uniform distance from the lesion. They are user-friendly and easy to handle at home, thereby reducing frequent hospital visits and improving patient compliance. The ease of use and cost-effectiveness of this target-based therapy with good results in early vitiligo, has led to an increased focus on its utility in vitiligo.8

Although handheld NB-UVB therapy has emerged as a novel and promising treatment modality in vitiligo, the existing studies are limited by their small sample size and heterogeneity in population, disease activity, dosage, and frequency of therapy, resulting in variable outcomes. This systemic review was therefore conducted to precisely evaluate the efficacy and safety of handheld NB-UVB device in the treatment of vitiligo.

Methods

Our systemic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.9 The study was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023459348).

Search strategy

Two reviewers (SS and DP) independently conducted systematic searches to identify articles published from 1 January 2002 to 28 November 2023 in the Embase, PubMed and Scopus databases using specific keywords (narrow band ultraviolet B, handheld, targeted, home, vitiligo) and MeSH terms (ultraviolet therapy, phototherapy, vitiligo, home environment) with appropriate Boolean operators [see Appendix S1 for more details]. Additionally, each reviewer performed a manual search, examined references of various articles, and searched for ongoing trials in ClinicalTrials.gov.

Study selection criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Monotherapy with a handheld narrow band UVB device with a lamp system for treatment of vitiligo.

-

2.

Studies which explicitly reported an absolute number of patients in terms of corresponding percentages of re-pigmentation or the incidence of side effects.

The eligible studies encompassed a range of research designs, including clinical trials, case series, systematic reviews, randomised controlled trials, and meta-analyses. Studies mentioning the specific NB-UVB devices by name were included, after meticulous verification of the technical specifications to confirm their nature as hand-held, portable home-based devices through product documentation; among such studies, those with sample size equal or greater than ten, were included. In situations where multiple studies emanated from a single centre, precedence was given to that which exhibited the largest sample size. No restrictions were imposed on the prior application of alternative therapeutic modalities in the vitiligo patient cohort studied. Geographical and linguistic factors were not deemed as limiting criteria. In the event of any discrepancies or inconsistencies, it was addressed through a process of consensus-building among the investigators or if required, by arbitration by a third reviewer (SK).

Data extraction

A comprehensive dataset encompassing study characteristics was generated, comprising parameters such as the primary author’s nomenclature, year of publication, study typology, detailed demographics of the study cohort (including vitiligo subtype, activity, body surface area [BSA] involvement, total sample size, average or median age of the study population), treatment particulars (initial therapeutic dosage, treatment frequency, dosage escalations and minimal dose erythema calculation), treatment duration and assessment of outcome quality.

The clinical efficacy data included a proportion of patients with re-pigmentation (> 25%, > 50% and > 75%) of skin over discrete time intervals spanning from 3 months to 12 months. Additionally, the percentages of re-pigmentation achieved in distinct anatomical regions, such as the head and neck, extremities, trunk, and acral areas, were meticulously catalogued. The data also included incidence of adverse events following therapy such as erythema, pruritus, burning sensation, dryness, skin atrophy, hyperpigmentation (abnormal skin darkening), herpetic lesions, blistering, the Koebner’s phenomenon and oedema (localised swelling).

The QoL outcomes were derived from studies employing distinct scoring systems, notably VitiQoL, Skindex 29 score, DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index) and Tjioe M questionnaire.8.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 22.005 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgiumhttp://www.medcalc.org; 2023). We determined the pooled proportions of re-pigmentation exceeding 25%, 50%, and 75%, achieved over a maximum duration of therapy with the device. To evaluate heterogeneity among the studies, we utilised the I2 statistics, where a value greater than 50% indicated significant heterogeneity. Random effect model was used for I2 statistics greater than 50% and the fixed model for I2 statistics less than 50%. Additionally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to further explore heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was carried out based on factors such as the number of patients, MED calculation, sessions per week, disease stability/activity, and response adjusted to time. Meta-analysis was used to generate a forest plot summarising the re-pigmentation response rate. Publication bias was evaluated using a Funnel plot and Egger’s regression test, taking into consideration the percentage of re-pigmentation. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in this context.

Results

Study characteristics

Through a systematic exploration of databases using predetermined search keywords, 250 articles were obtained. After a screening process, 13 studies were found suitable for inclusion, encompassing a total of 557 patients [Figure 1].8,10–21 Among these 13 studies, eight had a randomised controlled design,3,14,16–21 three were open-label single-arm studies,10–12 and two were open-label non-randomised comparative trials.8,15 The median age of patients was 30.4 years (range: 22.5–48.4 years). In the 13 studies, eight included patients of non-segmental vitiligo,8,10,13,14,16,19–21 two each included all types11,12 and focal/localised vitiligo,17,18 and one study included generalised vitiligo patients.15 Notably, seven studies recruited patients with only stable vitiligo.8,10,15,18–21 The extent of vitiligo involvement varied among the studies, with a reported BSA involvement from less than 2% to 25%,8,10,13,14–16 with other studies not specifying BSA involvement.11,12,17–21 Four studies used a starting dose of therapy based on MED calculation,13,15,17,20 two studies8,10 employed a fixed dose of 500 mJ/cm2, while the remaining studies used energy based on skin type or arbitrary doses that ranged from 50 mJ/cm2 to 400 mJ/cm2 and studies with predominantly patients of skin types IV, V and VI used higher initial energy doses. The increment of energy per sessions was 10–20% in five studies, > 20% in two studies, and < 10% in two studies [Table 1].

- Study selection process. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow chart.

| Study | Year of publication | Type of study | Duration of vitiligo in years | Disease stability | BSA involved | Age group | Type of vitiligo | Skin type | Total sample size | Age (in years) | Treatment characteristics | Treatment duration | Device used | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial dose of treatment | Dose increment per session | Treatment frequency | Minimal erythema dose (calculated/not calculated/not mentioned | |||||||||||||

| Singh et al.8 | 2023 | Open-label: Non-randomised | Median (range: 14 [0.3–40]) | Stable | < 2% | > 18 years | NSV | III, IV, V | 17 | Median age: 28; (range: 18–53) | 500 mJ/cm2 | Fixed | Daily | Not mentioned | Four months | Handheld NB-UVB comb device (V-Care Meditech Pvt. Ltd.) |

| Poolsuwan et al.19 | 2021 | RCT: double-arm |

Mean ± SD: 6.08 ± 3.22 |

Stable | NS | 18–65 years | NSV | III, IV, V | 36 | Mean 48.42 (37–65) |

Initial dose: 150 mJ/cm2 Mean cumulative dose: 14, 289.17 mJ/cm2 |

Increment of 15% for four sessions then by 10% Decrease by 50% of previous burning dose |

Thrice weekly | Not mentioned | Four months | DuaLightTM, TheraLight Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) |

| Khandpur et al.10 | 2020 | Open-label: single-arm | Mean ± SD: 4.9 ± 4.1 | Stable | < 2% | > 8 years | NSV | IV, V | 10 |

Mean: 30.4 (range: 21–54) |

500 mJ/cm2 | Fixed dose | Thrice weekly | Not calculated | Six months | NB-UVB comb (V-Care Meditech Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, India) |

| Thomas et al.13 | 2020 | RCT: three-arm | Median (range: 5 [3–11]) | Active | < 10% | > five years | NSV | I, II, III, IV,V, VI | 169 | Mean: 36.9 |

50 mJ/cm2 Maximum time of exposure: 13.42 minutes |

Increment by 10% till mild erythema | Three to four times weekly | Calculated | Nine months | |

| Zhang et al.15 | 2019 | Open-label |

Mean ± SD: 5.3 ± 7.4 |

Stable | >2% | > 16 years | Generalised | III, IV | 48 | Mean age: 33 + 12.2 |

Initial dose: 400 mJ/cm2 Maximum dose of energy: 3000 mJ/cm2 on body and 1500 mJ/cm2 for face Final cumulative dose: 84.1 ± 2.5 J/cm2 |

Increment by 20% till mild erythema | Thrice weekly | Calculated | Six months | Philips lamps (Shanghai Sigma High-tech Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China) |

| Liu et al.16 | 2019 | RCT: Double-arm | NS | Progressive and stable | <5% | > five years | NSV | III, IV | 52 | Mean (SD) age : 25.44 (1.43) |

Initial dose: 400 mJ/cm2 Maximum dose: 2500 mJ/cm2 |

Increment of 100 mj/cm2 (25%) till mild erythema | Thrice weekly | Not mentioned | Five months | Sigma SH1b handheld NB-UVB units (Sigma, Shanghai, China) |

| Van et al.17 | 2019 | Observational retrospective | NS | Active and stable | NS | 18–58 years | Localised | NS | 16 | NS | 20% less than MED |

Increment of 20% till mild erythema In cases where erythema was noted, we reduced the dose by 20% in the following treatment |

Once weekly | Calculated | Three months | NS |

| Tien Guan et al.18 | 2015 | RCT: Double-arm |

Median (range: 2 [1–16]) |

Stable | NS | NS | Focal | II, III, IV, V | 22 |

Median age: 23.5 (range: 15–40) Mean age: 34.6 years |

Power: 5.5 mW/cm2; Thrice weekly Total cumulative dose: 37.86 J/cm2 |

NS | Thrice weekly | Not mentioned | Six months |

(Daavlin Dermapal system) |

| Shan X et al.12 | 2014 | Open-label |

Mean ± SD: 3.7 ± 4.9 |

NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 93 | Mean: 22.5 (range: 2–65) |

Initial dose: 300 mJ/cm2 Maximum dose: 900 mj/cm2 |

Increment by 100 mj/cm2 (33%) till mild erythema | Thrice weekly | Not calculated | Twelve months | SS-01 UV phototherapy instrument (Shanghai Sigma High-tech Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China) which bears two Philips TL-9W/01 lamps |

| Eleftheriadou et al.14 | 2014 | RCT: Double-arm |

Mean ± SD: 11.36 ± 10.12 |

Active and stable | < 25% | > 5 years | NSV | I, II, III, IV,V, VI | 19 | Mean age:27.63; (range: 5–71) |

Based on Fitzpatrick skin type with initial time of exposure for skin type IV–VI: 30 sec and for skin type I, II, III: 15 sec, 20 sec, 25 sec, respectively Maximum time of exposure for skin type IV–VI: 6 min and for skin types I–III: 3 min, 4 min, 5 min, respectively |

Increment of 20% | Three to four times weekly | Calculated but not used as basis to start therapy | Four months | Two different handheld NB-UVB devices were explored: Dermfix 1000™ NB-UVB and Waldmann™ NB-UVB 109 |

| Goel et al.11 | 2012 | Open-label | Mean (range: 12 [0.1–18]) | NS | NS | 4–56 years | Generalised, segmental | IV, V | 50 | NS | Exposure for 2 mins at first sitting | 20% increment till mild erythema | Twice weekly | Not calculated | Six months | Narrow band UV spot phototherapy unit: 311 nm (PLS 9W/ 01) with mirror reflectors and adjustable spot size. (Dermaindia Spot Phototherapy Unit, Chennai) |

| Klahan and Asawanonda21 | 2009 | RCT: Double-arm |

Seven cases: 0–5 years Three cases: 6–10 years Five cases: > 10 years |

Stable | NS | NS | NSV | III, IV, V | 15 | Mean age: 41.67 (range: 27–65) | NS | NS | Twice weekly | Not mentioned | Three months | DuaLightTM (TheraLight Inc., Carlsbad, CA) |

| Asawanonda et al.20 | 2008 | RCT: Double-arm |

Five cases: 0–5 years Three cases: 6–10 years One case: 11–15 years One case: 16–20 years |

Stable | NS | > 16 years | NSV | III, IV | 10 | Mean age: 41.8 (range: 22–66) | 50% of MED | Increment of 10% or 5% | Twice weekly | Calculated | Six months | DuaLight™ (TheraLight. Inc. Carlsbad. CA Q20()8. USA |

NS: Not specified, SD: Standard deviation, NSV: Non-segmental vitiligo, Activity: At least single patch active for 12 months or newly diagnosed within three months and excluding rapidly progressive (50% increase in vitiligo lesion area, including any remote new lesions or increase in size of lesions in one month), MED: Minimum erythema dose. RCT: Randomised clinical trial, NB-UVB: Narrowband ultraviolet B.

In the majority of studies, the treatment regimen involved three sessions per week,10,12–16,18,19 whereas three studies employed twice-weekly sessions11,20,21 and one study each employed once-weekly17 and daily sessions.8 The median duration of treatment across the evaluated studies was six months (range: 3–12 months). The studies utilised various tools (VitiQoL, Skindex 29 score, DLQI, Tjioe M questionnaire,8 VIS-22) to assess QoL, which consistently demonstrated improvement compared to baseline.8,10,13–16 The characteristics of each study are mentioned in Table 1.

Clinical efficacy

Pooled analysis of efficacy

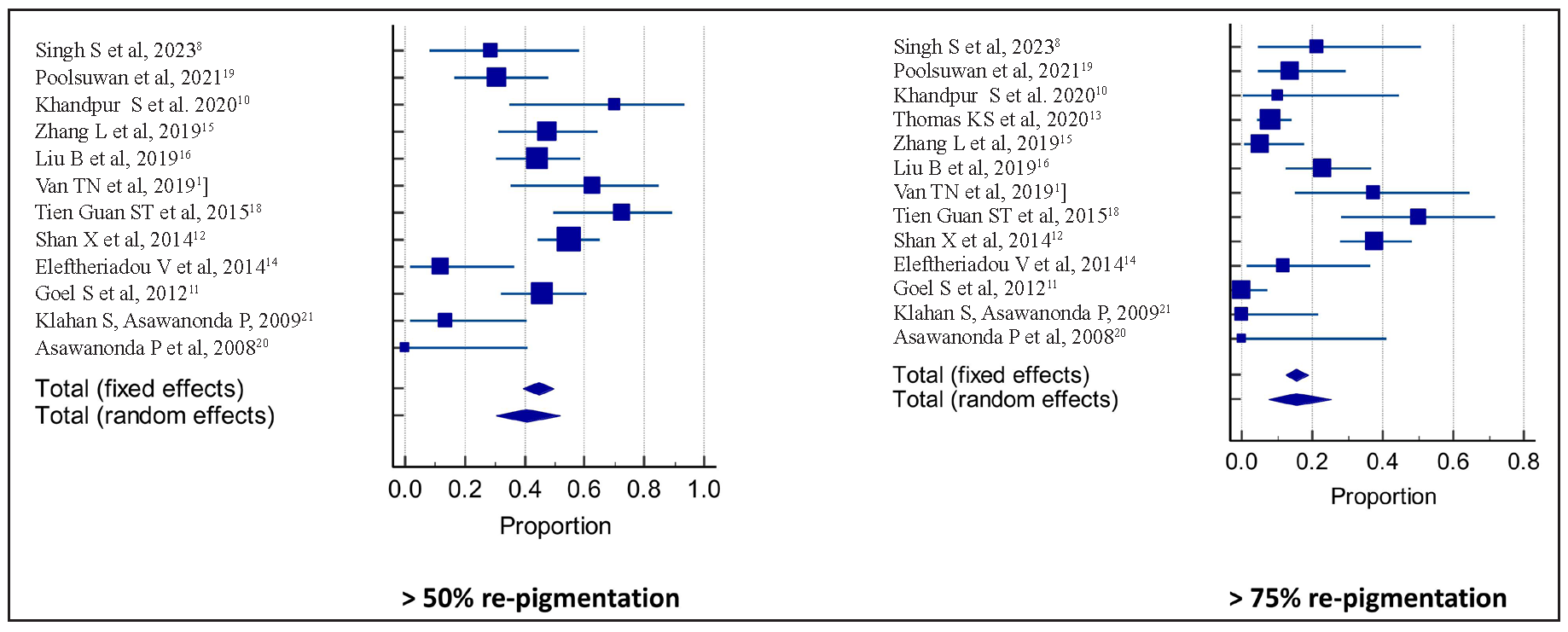

The response to therapy was graded as a percentage of re-pigmentation in the 13 studies, of which 9, 12, and 13 studies had provided proportions of patients attaining > 25%, > 50%, and > 75% re-pigmentation respectively, compared to baseline [see Appendix S2 for more details]. The pooled proportions of patients achieving > 25%, > 50%, and > 75% re-pigmentation compared to baseline were 63.6% (95% CI: 51.0–75.3%) of 297 patients, 40.8% (95% CI: 30.4–51.6%) of 370 patients and 15.4% (95% CI: 7.6–25.3%) of 506 patients over a median duration of six months of therapy. The pooled proportions of patients achieving > 25%, > 50%, and > 75% re-pigmentation compared to baseline in the non-randomised studies were 73.82% (95% CI: 67.59–79.4%) of 221 patients, 51.1% (95% CI: 44.4–57.8%) of 221 patients and 16.50% (95% CI: 83.2–95.2%) of 221 patients, respectively. The pooled proportions of patients achieving > 25%, > 50%, and > 75% re-pigmentation compared to baseline in the randomised studies were 52.38% (95% CI: 39.2–65.3%) of 59 patients, 27.54% (95% CI: 9.9–49.9%) of 95 patients and 13.03% (95% CI: 5.9–22.5%) of 231 patients, respectively. The details of the response to treatment in terms of the percentage of re-pigmentation in randomised and non-randomised studies are summarised in Table 2.

| Study | Sample size | > 25% re-pigmentation n/N | > 50% re-pigmentation n/N | > 75% re-pigmentation n/N | Pooled proportion (95% CI; I2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-randomised studies | |||||||

| Singh et al.8 | 17 | 8/14 (57.1%) | 4/14 (28.57%) | 3/14 (21.4%) | > 25% re-pigmentation | > 50% re-pigmentation | > 75% re-pigmentation |

| Khandpur et al.10 | 10 | 9/10 (90%) | 7/10 (70%) | 1/10 (10%) | 73.82% (95% CI: 67.59–79.4%; 0%) | 51.1% (95% CI: 44.4–57.8%; 19.73%) | 16.50% (95% CI: 83.2–95.2%; 91.01%) |

| Zhang et al.15 | 48 | 30/38 (78.9%) | 18/38 (47.36%) | 2/38 (5.26%) | |||

| Van et al.17 | 16 | 13/16 (81.25%) | 10/16 (62.5%) | 6/16 (37.5%) | |||

| Shan et al.12 | 93 | 66/93 (70.9%) | 51/93 (54.83%) | 35/93 (37.63%) | |||

| Goel et al.11 | 50 | 38/50 (76%) | 23/50 (46%) | 0/50 | |||

| Randomised studies | |||||||

| Poolsuwan et al.19 | 36 | NS | 11/36 (30.5%) | 5/36 (13.89%) | 52.38% (95% CI: 39.2–65.3%; 42.82%) | 27.54% (95% CI: 9.9–49.9%; 77.13%) | 13.03% (95% CI: 5.9–22.5%;79.04%) |

| Thomas et al.13 | 169 | NS | NS | 11/136 (8.1%) | |||

| Liu B et al.16 | 52 | 29/52 (55.76%) | 23/52 (44.23%) | 12/52 (23.1%) | |||

| Tien Guan et al.18 | 22 | NS | 16/22 (72.7%) | 11/22 (50%) | |||

| Eleftheriadou et al.14 | 19 | 3/17 (17.6%) | 2/17 (11.7%) | 2/17 (11.7%) | |||

| Klahan and Asawanonda21 | 15 | NS | 2/15 (13.33%) | 0/15 | |||

| Asawanonda et al.20 | 10 | 2/7 (28.6%) | 0/7 | 0/7 | |||

| Overall | 63.6% (51.0–75.3%; 77.1%) | 40.8% (30.4–51.6%; 75.9%) | 15.4% (7.6–25.3%; 85.9%) | ||||

Re-pigmentation based on anatomical sites

Three studies found > 50% re-pigmentation in vitiligo patches over the face and neck in 50% (45/90) of their cases, over the limbs in 50% (53/106) cases, and on the trunk in 39.1% (38/97) cases, but acral regions had only 2.5% (2/80) improvement.12,14,15 In the study by Thomas et al., > 75% re-pigmentation was seen in 32% (20/63) of head and neck lesions, 11% (7/79) of hands and feet macules, and 17% (16/92) of the patches present on the rest of the body.13 In the study by Zhang et al.,15 no significant differences in re-pigmentation based on site were observed, although face, trunk, and extremities showed better response than acral sites.15 In 11 studies, a total of 38 (11.3%) out of 334 patients had no response to therapy.8,10–12,14–18,20,21

Pooled analysis of adverse events

Handheld NB-UVB therapya-ssociated adverse events were reported in 12 studies with a total 542 patients (see Appendix S3 for more details). The most common side effect was erythema, with the pooled proportion of patients having erythema being 33.4% (95% CI: 19.3–49.2%) of 411 patients. Grades 3 and 4 erythema were reported in 27 and 15 patients, respectively. Pruritus was reported in five studies, with a pooled proportion of 22.1% (95% CI: 8.6–39.8%) among 227 patients.8,11,12,14,15 Four studies mentioned burning sensation, with a pooled proportion of 16.4% (95% CI: 6.4–29.9%) among 210 patients.8,12,15,16 Two studies reported dryness, with a pooled proportion of 9.8% (95% CI: 2.8–20.4%) among 112 patients.12,14 Hyperpigmentation around the vitiligo patch was reported in two studies, with a pooled proportion of 19.1% (95% CI: 11–28.9%) out of 71 patients.14,16 Blister formation was reported in two studies, with a pooled proportion of 9.7% (95% CI: 0.8–27.1%) out of 69 patients.8,16 One study each had mentioned skin thinning (two patients),13 cold sore (one patient),14 Koebner’s phenomenon (one patient),16 and oedema (three patients)8 as side effects of handheld NB-UVB therapy.

Heterogeneity

There was clinical heterogeneity noted in the included studies in terms of the study design, disease activity, BSA involvement, MED calculation, frequency of administration, and energy dosing. There was no significant heterogeneity noted among the non-randomised studies for pooled estimates of re-pigmentation of > 25% (I2 = 0%; 95% CI 0–%, 71.9, p = 0.49) and > 50% (I2 = 19.73%; 95% CI 0–64.4%, p = 0.28), but for > 75% repigmentation, they showed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 91.01%; 95% CI 83.2–95.2%, p < 0.01). There was significant heterogeneity noted among the randomised studies for pooled estimates of re-pigmentation of > 50% (I2 = 77.13%; 95% CI 25.54–92.9%, p = 0.01) and > 75% (I2 = 79.04%; 95% CI 59.01–89.28%, p < 0.01, but no such heterogeneity was noted for estimates of repigmentation of > 25% (I2 = 42.82%, p < 0.18), expect for). Based on sensitivity analysis, no articles were found to be a specific source of heterogeneity. There was significant heterogeneity for pooled estimates of erythema (I2 = 89.3%; 95% CI 81.9–93.7%, p < 0.001), burning sensation (I2 = 80.60%; 95% CI 49–92.6%, p < 0.01) and pruritus (I2 = 87.4%; 95% CI 72.9–94.1%, p < 0.01). There was insignificant statistical heterogeneity noted for dryness (I2 = 44.2%%, p = 0.18), hyperpigmentation (I2 = 0%, p = 0.82) and blistering (I2 = 67.1%, p = 0.08).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses of the percentage of re-pigmentation achieved based on the number of patients, MED calculation, vitiligo activity, the number of sessions per week and response adjusted to time were conducted. In studies with > 20 patients, there were significantly higher rates of > 25% re-pigmentation response (70.1% [95% CI: 60.7–78.7%] vs 55.5% [95% CI: 27.7–81.5%]; p = 0.02) and > 50% re-pigmentation response (48.6% [95% CI: 20.5–64.3%] vs 29.6% [95% CI: 11.1–52.5]; p = 0.002) compared to studies with < 20 patients. However, the pooled proportions of > 75% re-pigmentation showed no difference (16.6% [95% CI: 6.01–31.1%] vs 13.9% [95% CI: 4.6–27.1%]; p = 0.54] between studies including less than 20 patients and those including more patients. The number 20 was chosen to reflect the minimum sample size needed for a phase 1 clinical trial.

The patients who had used handheld NB-UVB therapy based on MED calculation showed no significantly better response for > 25% (67.5% [95% CI: 42.3–88.2%] vs 61.5% [95% CI: 45.8–76.1%]; p = 0.39), > 50% (36.0% [95% CI: 9.3–68.8%] vs 41.5% [95% CI: 29.9–53.5%]; p = 0.43) or > 75% (11.5% [95% CI: 3.4–23.7%) vs 17.1% [95% CI: 6.6–31.1%]; p = 0.08) re-pigmentation compared to patients who were treated without MED calculation.

The pooled > 25% re-pigmentation response was observed to be better in the four studies,8,10,15,20 which included only stable vitiligo than in the three studies14,16,17 that included both active or slowly progressive vitiligo along with stable disease (66.5% [95% CI: 44.3–85.4%] vs 51.5% [95% CI: 21.8–80.6%]; p = 0.06). The pooled > 50% (37.3% [95% CI: 20.6–55.7%] vs 38.9% [95% CI: 16.1–64.7%]; p = 0.80) and > 75% (13.9% [95% CI: 4.5–27.4%] vs 18.5% [95% CI: 7.8–32.6%]; p = 0.25) re-pigmentation responses reported in seven studies8,10,15,18–21 which included only stable vitiligo were not significantly different from the figures reported in studies13,14,16,17 which included both active or slowly progressive vitiligo along with stable disease.

The > 25% re-pigmentation response in patients who had received three to four sessions per week of therapy was not significantly different compared to that of patients receiving once/twice weekly and daily therapy (62.8% [95% CI: 40.0–85.8%] vs 65% [95% CI: 46.6–81.4%]; p = 0.72). However, > 50% (46.5% [95% CI: 33.9–59.2%] vs 30.7% [95% CI: 13.2–51.8%]; p = 0.006) and > 75% (19.5% [95% CI: 9.9–31.4%] vs 9.1% [95% CI: 0.34–27.76%]; p = 0.01) re-pigmentation were significantly better with three to four sessions per week when compared to once/twice weekly and daily therapy. However, there were no significant differences in > 25%, > 50% and > 75% re-pigmentation in those receiving three to four sessions per week when compared with those receiving daily therapy sessions (p-values of 0.08, 0.19 and 0.85, respectively).

The pooled proportions of patients achieving > 25%, > 50% and > 75% re-pigmentation compared to baseline at 12 weeks of therapy were 31.1% (95% CI: 9.6–58.3%; I2 = 94.4%, p < 0.01), 12.9% (95% CI: 3.1–28.1%; I2 = 88.8%, p < 0.01) and 6.50% (95% CI: 1.7–14.1%; I2 = 73.7%, p < 0.01), respectively. At 24 weeks, the corresponding proportions were 53.2% (95% CI: 24.5–80.7%; I2 = 96.5%, p < 0.01), 36.7% (95% CI: 15.8–60.5%; I2 = 94.5%, p < 0.01) and 11.1% (95% CI: 2.9–23.7%; I2 = 88.4%, p < 0.01).

Risk of bias

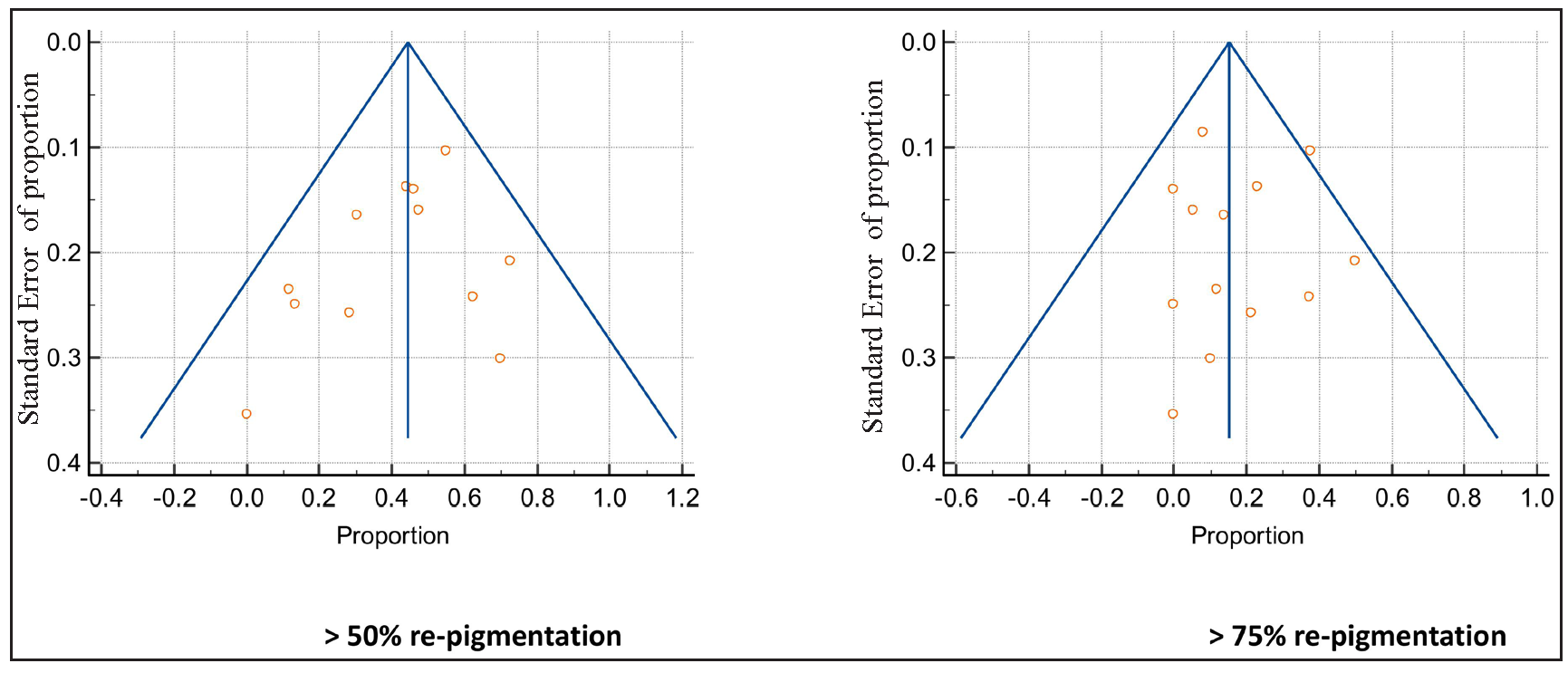

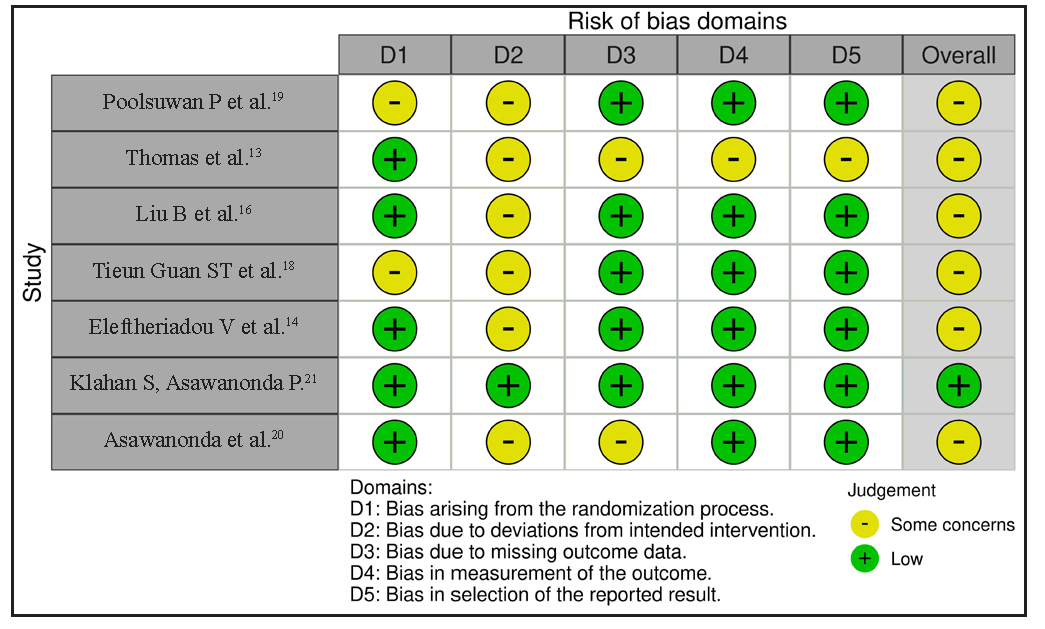

In the included studies, five studies were open-label, thereby inherently carrying the risk of selection bias8,10–12,15 with none of them having a score of less than four on the Newcastle Ottawa scale adapted for single arm. Funnel plot of the articles based on re-pigmentation > 25%, > 50% and > 75% showed no evidence of publication bias on visual inspection [Figure 2]. Following Cochrane guidelines,22 all randomised studies were found to have moderate to good quality with low risk of bias for the relevant outcome of interest [Table 3 and Figure 3]. The p value for the Egger’s regression test was statistically insignificant for > 25% (p = 0.83), > 50% (p = 0.27) and > 75% (p = 0.80) re-pigmentation.

- Pooled percentage of re-pigmentation more than 50% and 75%. Forest Plots. Squares and horizontal lines represent individual study estimates and 95% CIs, respectively.

- Funnel plots. Central line shows summary estimates and the lines on either side show 95% CI. (Circles represent individual studies.)

| Study | Selection | Outcome | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singh et al.8 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Khandpur et al.10 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Zhang et al.15 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Van et al.17 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Shan et al.12 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Goel et al.11 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Values are assigned equivalent to the number of stars for each parameters in a particular study.

- Assessment of the risk of bias via the Cochrane RoB 2 tool displayed by means of a traffic light plot of the risk of bias of each included clinical study.

Discussion

This review offers a comprehensive analysis of the clinical efficacy and safety profile of the handheld NB-UVB portable device in treating vitiligo. Notably, our review’s main strength lies in the extensive analysis of a large number of patients undergoing NB-UVB handheld therapy, assessing both clinical efficacy and toxicity profile. We also addressed various co-factors such as the extent and type of vitiligo, skin type, disease stability/activity, necessity of MED calculation, initial dose, session-to-session energy increment and energy reduction based on side effects and sessions per week, and formulated a basic norm for effective clinical outcomes with the device for treatment of vitiligo (see Appendix S4 for more details).

The clinical efficacy, categorised as > 25%, > 50% and > 75% re-pigmentation, was observed in 63.6%, 40.8% and 15.4% of patients, respectively, over a six-month period. Additionally, 11.3% (38 out of 334) of patients exhibited no response. Notably, re-pigmentation was most prominent on the face and neck, followed by the trunk and extremities. Conversely, the least response was noted over acral sites and bony prominences.

Clinical efficacy was achieved even without MED calculation, showing a better response, though not statistically significant. However, re-pigmentation more than 25% was more apparent in patients where the dose calculation was based on MED, though the significance was not established. Similarly, early (> 25%) re-pigmentation response was notable in patients with stable vitiligo compared to those with active or slow progression of the disease, although not statistically significant.

A slightly more pronounced > 50% and > 75% re-pigmentation was observed in studies including active and slowly progressive vitiligo in addition to stable vitiligo as compared to studies on exclusively stable patients, but this was not statistically significant. Notably, three to four treatment sessions per week resulted in significantly greater > 50% and > 75% re-pigmentation compared to sessions held twice or once weekly. However, the re-pigmentation response was not significantly different between three and four sessions a week and daily treatment regimes. The common side effects observed were erythema (27%) followed by pruritus (26.6%). The handheld NB-UVB device was found to have no major or serious side effects, making it suitable for home use with proper patient instructions.

In a systematic review and meta analysis by Bae et al., 74.2% out of 232 vitiligo patients showed > 25% re-pigmentation with six months of conventional NB-UVB therapy3 which was greater compared to a 63.6% response to the handheld NB-UVB devices in our analysis, probably because of the heterogeneity in duration of therapy, with six studies8,14,16,17,19,21 having a treatment period of less than six months. In the same review, around 37.4% and 19.2% of patients showed > 50% and > 75% re-pigmentation at six months with NB-UVB therapy, which was similar to our analysis of 40.8% and 15.4%, respectively.3 In the Bae et al. review, > 50% re-pigmentation response was seen in 60% of patients on the face and neck, 46% of patients on the trunk, 35% of patients over extremities and 2.5% of patients on acral areas, which was similar to our analysis.3 The handheld NB-UVB device has also been shown to have similar efficacy to the whole-body chamber in various studies;8,15,16 moreover, the compliance with handheld therapy is significantly better than hospital-based therapy.8 The adverse event profile and QoL improvement have also been found comparable between handheld and whole-body chamber NB-UVB therapies.8,15 In the study by Kumar et al., 17% of cases had > 75% re-pigmentation after one year of whole-body chamber NB-UVB therapies.23 In contrast to our findings, studies by Kanwar et al., Njoo et al. and Scherschun et al., reported a higher proportion of improvement (> 75% re-pigmentation) with whole-body chamber NB-UVB therapy in vitiligo, which in turn could be explained by the smaller sample size in these stuides.24–26

PUVA therapy is an effective therapy in vitiligo, although it has several limitations like nausea, phototoxic reaction and risk for skin cancer and cannot be used in children and pregnant women.3 In this study by Bae et al., PUVA therapy showed > 25%, > 50% and > 75% re-pigmentation in 51.4%, 23.5% and 8.5% of patients, respectively, at six months, which was comparatively less than with handheld NB-UVB therapy as observed in our analysis.3

In a study by Sun et al., no difference in > 75% re-pigmentation response was observed among users of 308 nm excimer laser, 308 nm excimer lamp and NB-UVB therapy (whole-body (13 or 48 TL 100 W/01 tubes) and foot units (8 TL 36 W/01 tubes).27 However, a greater proportion of patients achieved > 50% re-pigmentation with the 308 nm excimer compared to NB-UVB. In a study by Park et al., mean re-pigmentation achieved in ten patients treated for three months with the 308 nm excimer laser and 311 nm titanium – sapphire laser was 49.9% and 52.8%, respectively – they were better compared to handheld NB-UVB.28 In a study by Poolsuwan et al., 308 nm excimer light showed significant reduction in VASI score with higher grade of re-pigmentation compared to the targeted NB-UVB therapy (p < 0.001), although no significant difference in cumulative dose (p = 0.06) and side effect profile (p = 0.08) were noted.19

Recently, home-based NB-UVB phototherapy has attracted attention due to the drawbacks of hospital-based treatment methods. With its single-, double- or triple-panelled units, it presents a promising home-based therapy option that offers accessibility, affordability and patient convenience. Based on our review, we devised effective ways to use the handheld device. We suggest calibrating the device every three months and activating it for 45 seconds before exposing it to vitiligo-affected areas to harness peak energy.8,10 Additionally, switching off the device after five minutes is advised due to a significant drop in energy emission.8,29,30 It is evident that the handheld NB-UVB device has proved as effective as the standard whole-body hospital-based NB-UVB therapy,8,15,16 and even superior to PUVA therapy based on our review and literature search. While some studies indicate that excimer laser may offer a better response compared to the handheld device, further research utilising a predefined protocol for handheld NB-UVB should be conducted for a more accurate comparison. Further, handheld NB-UVB can be combined with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids in the treatment of early/recent onset of vitiligo disease to enhance re-pigmentation as per European guidelines.

Limitations

This analysis included heterogeneous studies in terms of study design, types of vitiligo, activity and BSA of vitiligo, different NB-UVB handheld therapy protocols and devices used, although the random effects model used in our study analysis could account for statistical heterogeneity. There was a small sample size in a number of evaluated studies, thereby limiting the strength of these observations. The individual duration of illness or extent of involvement of vitiligo could not be determined, preventing further subgroup analysis based on these parameters. It is possible that pertinent studies may have been not included, given the inherent limitations of database literature search.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed the clinical efficacy and safety of the handheld NB-UVB portable device in the treatment of vitiligo. Similar extents of re-pigmentation (good [> 50%] to excellent [> 75%]) were seen with both stable and active vitiligo. The initial dose of energy may not necessarily require MED calculation beforehand, but it is essential to undergo a minimum of three sessions per week for significant re-pigmentation. Furthermore, our analysis has laid the foundation for future research, advocating a redefined protocol for improved clinical outcomes and also its routine use in daily clinical practice for the treatment of vitiligo.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- The prevalence of vitiligo: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163806.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiligo: Patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:32-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Phototherapy for vitiligo: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:666-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- What is new in narrow-band ultraviolet-b therapy for vitiligo? Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:234-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and molecular aspects of vitiligo treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1509.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of skin expression profiles of patients with vitiligo treated with narrow-band uvb therapy by targeted rna-seq. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:843-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Home phototherapy in vitiligo. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2017;33:241-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An open-label non-randomized preliminary noninferiority study comparing home-based handheld narrow-band UVB comb device with standard hospital-based whole-body narrow-band UVB therapy in localized vitiligo. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;14:510-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Narrow-band ultraviolet B comb as an effective home-based phototherapy device for limited or localized non-segmental vitiligo: A pilot, open-label, single-arm clinical study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:298-301.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of vitiligo with hand held nbuvb phototherapy unit-study of 50 patients. Int J Inst Pharm Life Sciences. 2012;2:227-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Narrow-band ultraviolet B home phototherapy in vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:336-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randomized controlled trial of topical corticosteroid and home-based narrowband ultraviolet B for active and limited vitiligo: Results of the HI-Light Vitiligo Trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:828-39.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feasibility, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial of hand-held NB-UVB phototherapy for the treatment of vitiligo at home (HI-Light trial: Home Intervention of Light therapy) Trials. 2014;15:51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of efficacy and safety profile for home NB-UVB vs. outpatient NB-UVB in the treatment of non-segmental vitiligo: A prospective cohort study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2019;35:261-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home vs hospital narrowband UVB treatment by a hand-held unit for new-onset vitiligo: A pilot randomized controlled study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2020;36:14-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment of vitiligo Vietnamese patients with Vitilinex® herbal bio-actives in combination with phototherapy. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:283-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Randomized, parallel group trial comparing home-based phototherapy with institution-based 308 excimer lamp for the treatment of focal vitiligo vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:733-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative efficacy between localized 308-nm excimer light and targeted 311-nm narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy in vitiligo: A randomized, single-blind comparison study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2021;37:123-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targeted broadband ultraviolet B phototherapy produces similar responses to targeted narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for vitiligo: A randomized, double-blind study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:376-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topical tacrolimus may enhance repigmentation with targeted narrowband ultraviolet B to treat vitiligo: A randomized, controlled study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e1029-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

- Evaluation of narrow-band UVB phototherapy in 150 patients with vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:162-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of generalized vitiligo in children with narrow-band (TL-01) UVB radiation therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:245-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narrow-band UVB for the treatment of vitiligo: An emerging effective and well-tolerated therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:57-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narrow-band ultraviolet B is a useful and well-tolerated treatment for vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:999-1003.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of 308-nm excimer laser on vitiligo: A systemic review of randomized controlled trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:347-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comparative clinical trial to evaluate efficacy and safety of the 308-nm excimer laser and the gain-switched 311-nm titanium:sapphire laser in the treatment of vitiligo. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2020;36:97-104.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handheld narrow band ultraviolet B comb as home phototherapy device for localised vitiligo: Dosimetry and calibration. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:78-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portable home phototherapy for vitiligo. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:603-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]