Translate this page into:

Medical device regulation in India: What dermatologists need to know

2 Department of Pediatrics, Medical College, Kolkata, India

Correspondence Address:

Sandeep Lahiry

Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata

India

| How to cite this article: Lahiry S, Sinha R, Chatterjee S. Medical device regulation in India: What dermatologists need to know. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2019;85:133-137 |

Introduction

Ever wondered as a dermatologist, how the medical instruments we use are regulated? What quality checks are in place to ensure the laser we use is safe for our patients?

To be honest, many feel such intricacies as too “nonmedical” to even qualify for a discussion; the premise being “how can a regulatory policy affect my clinical practice?” However, device regulations impact public health tremendously.

In general, most dermatologists are familiar with the regulatory requirements for drug approval but are much less informed about the different regulations that apply to medical devices. Moreover, there is lack of knowledge regarding reporting of adverse events related to medical devices, primarily because the regulations are far less stringent in the post-approval marketing phase, particularly in India.

Clinical dermatology practice has now expanded to include the use of devices in sophisticated cosmetic procedures. This is a consequence of not only the rising interest in aesthetic medicine but also the economic pressures in managed care plans, as well as stringent regulation on private practice. However, the increased reliance on new cosmetic procedures and devices has also resulted in confusion over their real benefits and risks. This confusion has arisen, in part, as a result of aggressive marketing by manufacturers.

Therefore, as academicians, we must be informed of key regulatory policies concerning medical devices, so that we understand the data supporting the risks and benefits of a medical device, as well as the limitations of the evaluation of these devices, rather than relying solely on the sales force of the manufacturers entreating us to purchase their “FDA-approved” device. This article simplifies aspects regarding regulation of medical devices in India.

The Medical Devices Rule (2017)

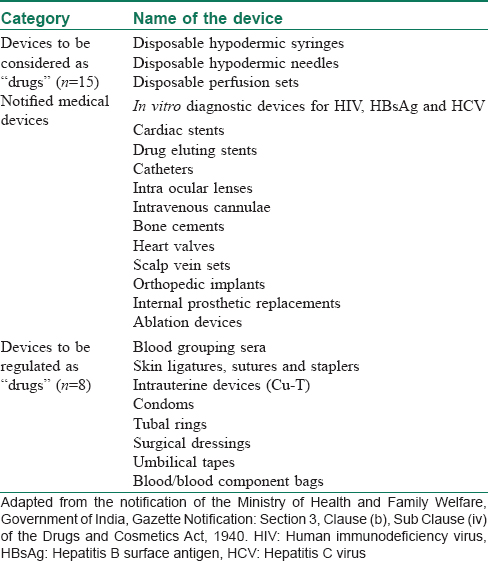

There was no medical device regulation in India before 2005. The government proposed regulatory guidelines for premarket approval of medical devices in 2008, through amendments to the existing 1945 Drug and Cosmetics Rules (“RULES”). A new set of guidelines was introduced in 2012 that applied drug rules to medical devices.[1] The guidelines were updated in 2013, although the updated rule brought all medical devices sold in India in the purview of Drug Controller General of India, under the Central Drug Standard Control Organization. However, by virtue of the RULES, many medical devices are still regulated as “drugs.” Such devices are referred as “notified medical devices.”[2],[3] [Table - 1] depicts the current list of notified medical devices in India.

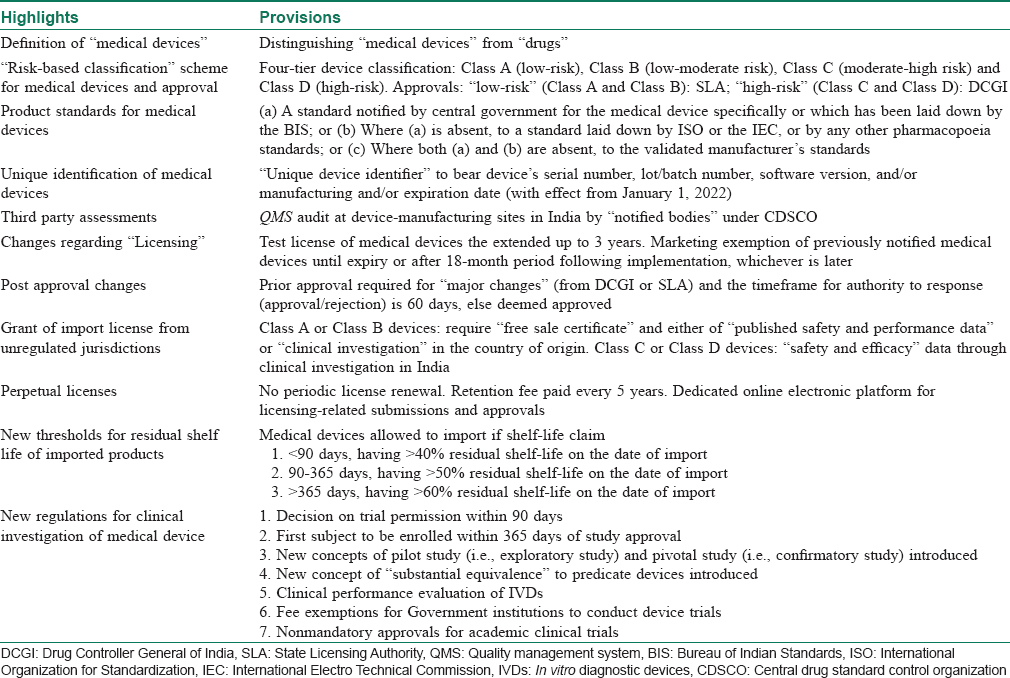

On January 31st, 2017, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare formally announced the Medical Devices Rules, 2017 (MDR 2017), that has been enforced from January 1, 2018.[4],[5] Along with the several amendments, the new rule has categorically differentiated “medical devices” from drugs/pharmaceuticals for the purpose of legislative clarification. The key highlights of the new 2017 rules have been summarized in [Table - 2].

In relation to dermatology, medical devices used in patient care (lasers, surgical equipments, fillers, etc.) are also covered under MDR 2017. They all continue to be designated as “devices” even if there is a contradiction with RULES, and the definitions of which still apply to all medical devices.[5] This clarification was much necessary from a legislative standpoint.

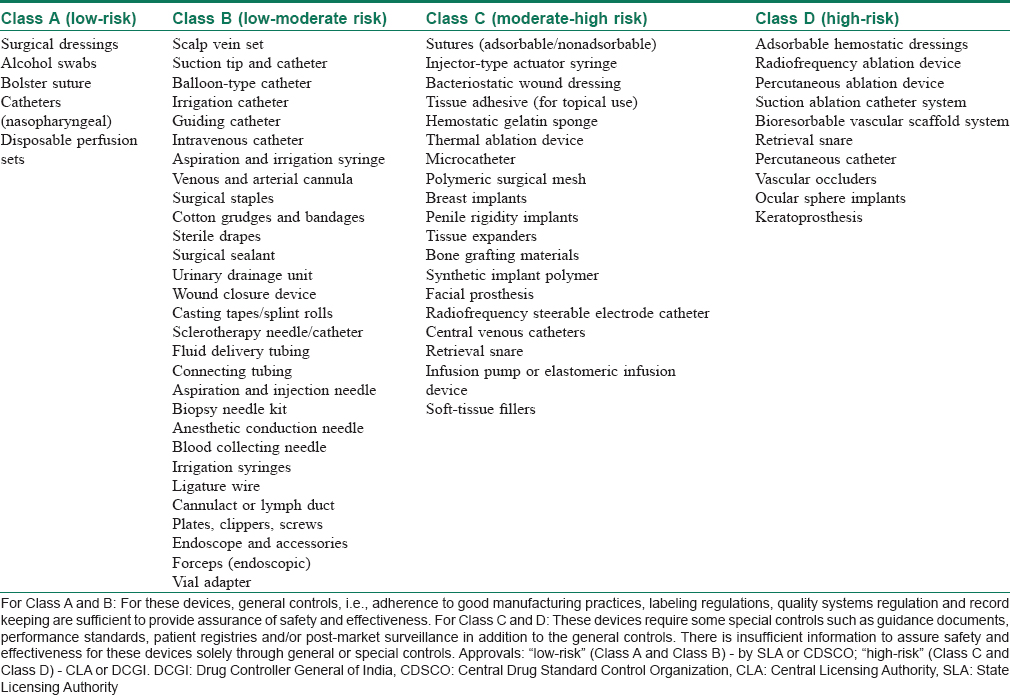

“Risk-Based Classification” Scheme

On the basis of European model, the classification of medical devices under MDR 2017 is based on “associated risks.” Devices now fall broadly under four categories, namely “low-risk” – Class A, “low-moderate risk” – Class B, “moderate risk” – Class C or “high-risk” – Class D. The classification also takes into consideration the “level of invasiveness” and “duration of use in the body.”[5] [Table - 3] depicts different devices relevant to dermatology/surgical/aesthetics included in various classes under MDR 2017.

Several dermatological instruments including manual surgical instruments, hydrophilic wound dressings, wound hydrogels, cotton, gauze for external use and wound drains are now classified under “low-risk” devices. These devices present minimal potential harm to the user and are often simple in design. The risks are those that can be mitigated through labeling, quality assurance and/or good manufacturing processes.

“High-risk” devices such as wound dressings that include human cells, injectable soft-tissue fillers, breast implants and adhesion barriers are those that require stringent controls. Although important for clinical use, these devices represent a potential for risk of illness or injury where the risks are not well-defined, understood or known.

Soft Tissue Fillers: An Example of a Class C Medical Device

Soft tissue fillers are regulated as Class C (moderate risk) medical devices, as the types of materials approved for soft tissue filler vary from biologic to synthetic materials. Soft tissue fillers are generally indicated for mid to deep dermal injections for the correction of wrinkles. Some filler devices (e.g. Sculptra, poly-l-lactic acid) are approved only for use in immunocompromised states (e.g. HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy). Labeling of such devices contain warnings that should be derived from a clinical study. In fact, for any Class C device, licensing approval must be based on credible safety and efficacy data from a regulatory study (ideally randomized, controlled, multicentric using a split-face design for within subject control). However, there are many cases where physicians use products without adequate safety data.

For instance, Radiesse (calcium hydroxyapatite; Bioform Medical Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA), which is FDA approved for use in bone augmentation, is not approved for the indication of cosmetic use as a soft tissue filler, although physicians are using it for that purpose. There are no long-term studies on the effect of this radiopaque substance in the skin.

In many cases, clinical studies conducted by manufacturers generally involve evaluation of device injection into periorbital and nasolabial folds, considered representative of moderate-to-severe facial wrinkles and folds. To ensure credible safety data, clinical studies with soft tissue filler must have standard efficacy measures. The primary endpoint for evaluation of wrinkle severity should ideally use photographic assessment, and assessment of the wrinkles using a validated scale that was acceptable to Drug Controller General of India. Evaluation of subjects should ideally occur at scheduled visits at varied intervals up to 6 months. The duration of the study must be determined by the durability of the filler material. Device safety must be assessed through the evaluation of incidence and severity of local and systemic adverse events.

How Does Central Drug Standard Control Organization Regulate Medical Devices?

All approvals for “low-risk” devices (Class A and B) are undertaken by State Licensing Authority, whereas for “high-risk” devices (Class C and D) decisions are made by the Drug Controller General of India, the Central Licensing Authority in India. However, there are specified timelines for such approvals. For example, the review of a marketing application for a Class C or Class D medical device must be completed within 45 days from the date of the online submission. Inspection of the manufacturing site for medical devices classified as Class C or Class D must be completed within 60 days from the date of the initial application. Furthermore, after completion of the inspection, the inspection team must forward the inspection report to the licensing authority who then has 45 days to make a final approval determination.

Consequently, a system of “Third Party Conformity Assessment and Certification” has been proposed. It provides a unique provision of quality management system that will be implemented to determine systemic controls applied in the manufacturing process that determines the safety and performance of a medical device. Under MDR 2017, quality management system audit at manufacturing sites will be done by notified bodies (legal entities with ISO-13485, accredited by the National Accreditation Board for Certification Bodies). This essentially replicates provisions in the European model (Regulation (EU) 2017/745).

Many dermatologists import surgical instruments, primarily through third-party vendors. With regards to grant of import license of such medical devices, license to import Class A or B devices from “unregulated jurisdictions” (countries other than US, Canada, Japan, European Union and Australia) now requires a “free sale certificate,” which should contain “published safety and performance data or clinical investigation” in the country of origin. However, for Class C and D, a license can be granted only on establishment of definite safety and efficacy from clinical studies undertaken in India.

Perpetual Licensing

Under the new rule, medical device licenses that are granted will remain valid as long as license fees are paid every 5 years from the date of issue, unless the license is suspended or cancelled by the licensing authority. If the licensee fails to pay the required license retention fee on or before the due date, the entity will be liable to pay late fees in addition to the license retention fee. If the licensee fails to deposit the license retention fee within 180 days, the license is deemed to have been cancelled.

Unique Device Identifier

There have been several incidences of defective or substandard instruments in the market that has upset the surgeon community by large. Absence of robust redressal mechanism makes it worse. Under the new rule, such problem is supposed to be mitigated through a provision prompt product recall. Every medical device will now bear a “unique device identifier” (starting January 1, 2022), which is basically a global trade item number and the production identifier that has the manufacturing process details such as device's serial number, lot/batch number, date of expiry, etc. This will enable an advanced device tracking system for device surveillance (pre- and postmarketing) that are currently under process.

Regulatory Framework for Clinical Trials

The must-awaited regulatory framework for clinical trials involving medical devices is slated to streamline the existing approval timelines. Although the complete framework has not been finalized yet, some of the major provisions include (i) fixed period of 90 days for licensing authority for granting study approvals; (ii) first subject recruitment to be completed within 365 days of approval date; (iii) all clinical investigations must be registered with the Clinical Trial Registry of India before enrolling the first participant; (iv) no approval is required for academic clinical studies on licensed medical devices where the Ethics Committee approves such a study and the data generated during the study are not used for a marketing application; (v) introduction of novel concepts such as “pivotal” studies, “pilot” studies and terms such as “substantial equivalence” to predicate investigational devices in respect to other devices; and (iv) annual status reports to be submitted to the licensing authority, including notification of termination of the study, and the reporting of suspected or unexpected serious adverse events occurring during the clinical investigation within 14 days of knowledge of its occurrence.

How to Report Adverse Events Related to Medical Devices?

In 2015, the Materiovigilance Programme of India was launched, being coordinated by the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission at Ghaziabad.[6] The purpose of the program is to study and follow medical device associated adverse events and enable dangerous ones to be withdrawn from the market. The Commission functions as the national coordination center and the Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute of Medical Sciences and Technology in Thiruvananthapuram acts as the collaborating center. Technical support is being provided by the National Health System Resource Centre in New Delhi.

Although Materiovigilance Programme of India was envisaged as a nation-wide program involving district hospitals, medical colleges and corporate healthcare institutions, even after 3 years since its launch, only a few hospitals have Materiovigilance Programme of India cells. Some institutions have appointed research fellows to monitor medical device associated adverse events, but this is a recent development. The program is still in its infancy. This makes it a moral responsibility of the healthcare provider to report medical device-linked adverse events. A medical device associated adverse event reporting form has been devised, which can be used to report any adverse event related to medical devices. The forms can be directly emailed to Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute of Medical Sciences and Technology at mvpi@sctimst.ac.in.[7]

Government Policy on Procurement of Medical Devices

On March 15, 2018, the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, released a draft guideline for implementation of the provisions of the Public Procurement Order, 2017, with respect to public procurement of medical devices.[8]

The Department of Pharmaceutical has proposed that domestically sourced components have to contribute to 25–50% of the cost of medical devices procured by the government, depending on the category of the device. Yet, these criteria apply to tenders valued at INR 50 lakhs and below. For tenders valued over INR 50 lakhs, the contract for procurement would be awarded to the domestic firm if it is the lowest bidder. In case the local supplier is not the lowest bidder, the domestic firm will be invited to match the lowest bid for 50% of the contract—a provision that both multinational and domestic firms have objected to.

Comments

Of late, there is a growing trend of powerful enticement in the positioning of various devices on television and in print media, with physicians providing testimonials about the benefit of their use. Moreover, consumer demanding for cosmetic procedures has become market-driven. Hence, dermatologists must take informed decisions while purchasing medical devices, and rely on real clinical effectiveness and safety data, rather than trust on a brand.

The Government of India has identified the medical device industry as a focus industry for its flagship Make in India program. It is especially committed in easing the processes and compliances for doing a business of medical devices in India. With the new medical devices rule, there is an attempt to ease out stringent norms for obtaining licensing. Moreover, limiting manufacturer–regulator interface through a digital platform could promote the local medical device industry. Newer schemes such as the launch of a new medical device parks in which government will provide fiscal and monetary incentives which gives lot of confidence to stakeholders in the medical device industry.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Overview of Indian Medical Device Industry and Healthcare Statistics. Available from: https://www.emergogroup.com/resources/market-india. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 28].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

List of Notified Medical Devices. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2010. p. 1. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/writereaddata/list-of-notified-medical-device(1).pdf. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 28].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

No. DCG (I/Misc./2017 (68). New Delhi; 2017. Available from: https://www.emergogroup.com/sites/default/files/india_cdsco_notice_29_6_2017.pdf. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 28].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Health Ministry Notifies Medical Devices Rules 2017. Press Information Bureau, Government of India; 2017. Available from: http://www.pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=157955. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 28].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Medical Device Rules, 2017: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2017. p. 108. Available from: http://www. 164.100.158.44/showfile.php?lid=4168. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 28].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Launch of MaterioVigilance Programme of India. Indian Pharmacopeia Commission. Available from: http://www.ipc.gov.in/8-category-en/432-launch-of-materiovigilance-programme-of-india-mvpi.html. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 28].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Medical Device Associated Adverse Event Reporting Form. MaterioVigilance Programme of India. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/writereaddata/MDadverseevent.pdf. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 28].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Guidelines for Implementation of Public Procurement Order; 2017. Available from: `http://www.pharmaceuticals.gov.in/sites/default/files/Guidelines%20for%20implementation%20of%20Public%20procurement.pdf. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 28].

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

7,230

PDF downloads

2,446