Translate this page into:

A novel KRT6A mutation in a case of pachyonychia congenita from India

2 Centre for Dermatology and Genetic Medicine, Division of Biological Chemistry and Drug Discovery, School of Life Sciences, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK

3 Pachyonychia Congenita Project, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

4 Centre for Dermatology and Genetic Medicine, Division of Biological Chemistry and Drug Discovery, School of Life Sciences, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK; Pachyonychia Congenita Project, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA,

Correspondence Address:

Frances J.D Smith

Pachyonychia Congenita Project, Salt Lake City, Utah

| How to cite this article: Tiwary AK, Wilson NJ, Schwartz ME, Smith FJ. A novel KRT6A mutation in a case of pachyonychia congenita from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:95-98 |

Sir,

Pachyonychia congenita (MIM #615726, #615728, #615735, #167200, #167210) is a rare, autosomal dominant disorder that primarily affects the skin and nails. Severe plantar pain is the most debilitating symptom of this disorder. The most common features in this disease are palmoplantar keratoderma and nail dystrophy, often accompanied by oral leukokeratosis, various types of cysts, follicular hyperkeratosis, palmoplantar hyperhidrosis and sometimes, natal teeth.[1] Pachyonychia congenita is caused by a mutation in any one of the five keratin genes: KRT6A, KRT6B, KRT6C, KRT16 or KRT17.[2] The majority of these are missense mutations with a smaller number of deletions, insertions and splice site mutations.

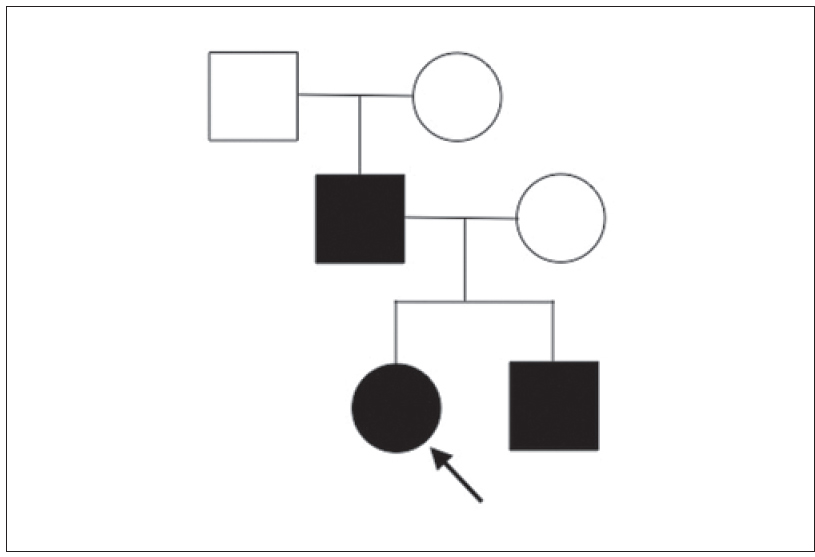

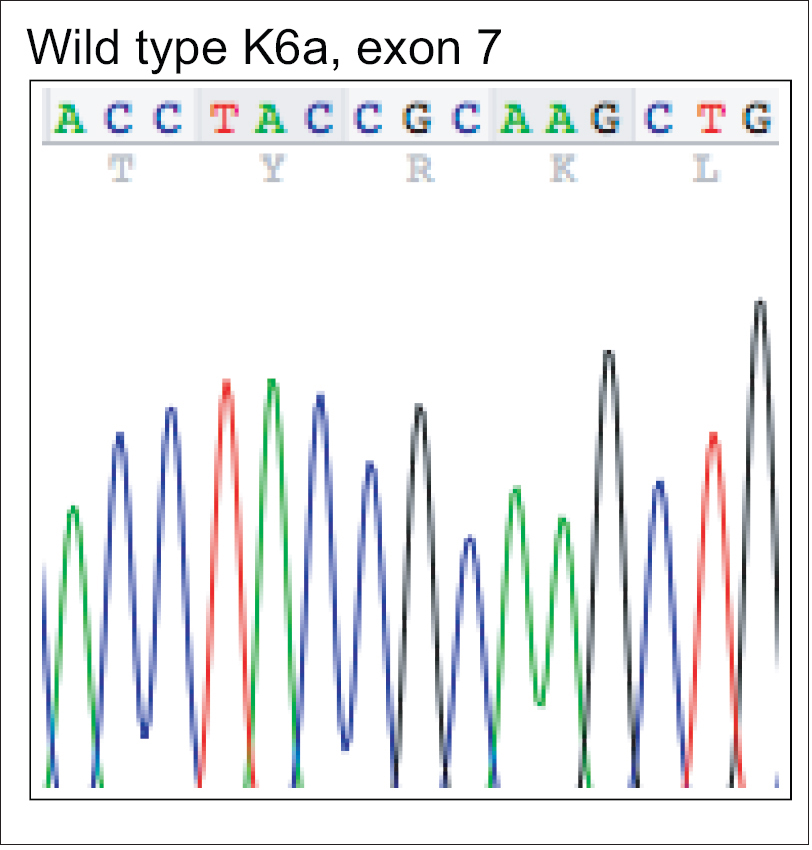

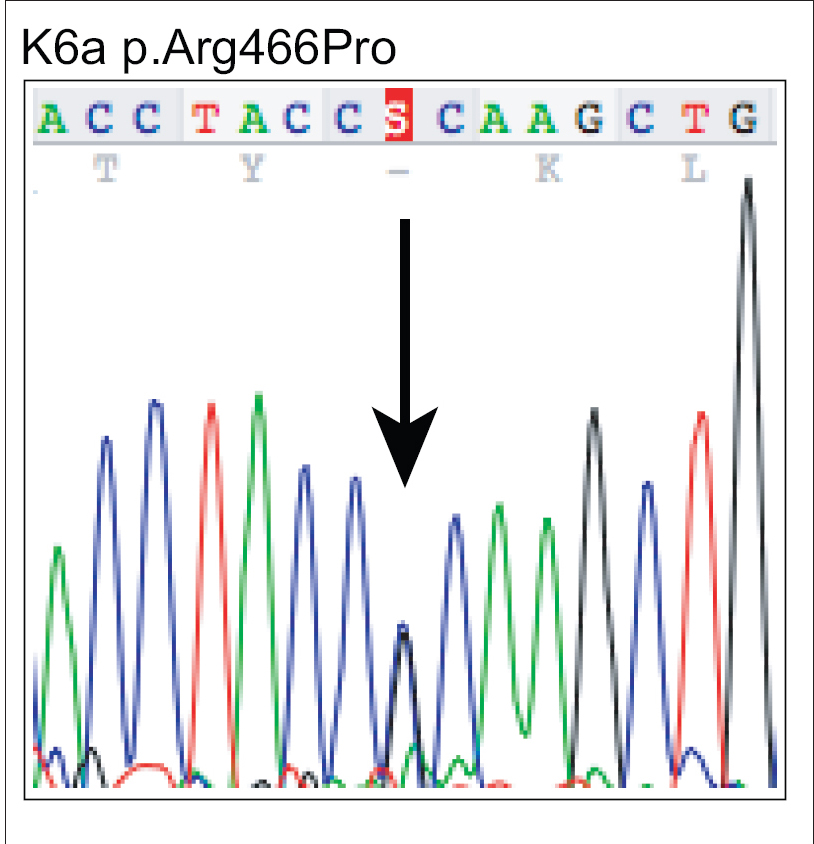

A 17-year-old woman from India presented with thickening of the fingernails and toenails noted since early infancy, painful plantar keratoderma, oral leukokeratosis, cysts and follicular hyperkeratosis [Figure - 1]a,[Figure - 1]b,[Figure - 1]c. Treatment of the keratoderma with topical keratolytics and emollients earlier were of little benefit. Her father, 45 years of age, had similar clinical manifestations involving the palms, soles and nails since early infancy and the lesions were progressive until into his forties. Her mother was unaffected. Her 12-year-old brother also has similar painful palmoplantar keratoderma with thickened nails which were noticed since infancy. The clinical features and autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance were suggestive of a diagnosis of pachyonychia congenita [Figure - 2] and the patient was referred to the Pachyonychia Congenita Project (www.pachyonychia.org) for confirmation of the diagnosis by genetic testing. Samples were obtained with informed consent and following ethical approval from a Western Institutional Review Board that complies with principles of the Helsinki Accords. Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid was extracted from the saliva, which was collected in an Oragene deoxyribonucleic acid sample collection kit (deoxyribonucleic acid Genotek, Ontario, Canada). Mutation analysis of the five known pachyonychia congenita keratin genes was performed by polymerase chain reaction amplification and Sanger sequencing, as described by Wilson et al., 2014.[2] A heterozygous missense mutation was identified in the proband in KRT6A. The mutation is designated as K6a p. Arg466Pro; c. 1397G>C [Figure - 3]. We were unable to find any previous reports of this mutation, which occurs in exon 7 in the 2B domain of K6a, one of the known mutation hotspot regions. In silico prediction program 'Mutation Taster' predicts this to be a disease-causing variant. It is not reported in the single nucleotide polymorphism database, 1000 Genomes Project, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) or the Exome Aggregation Consortium Browser. Unfortunately, no other family members were available for testing.

|

| Figure 1a: Severe plantar keratoderma with fissuring in the proband |

|

| Figure 1b: Thickened toenails in the proband |

|

| Figure 1c: Oral leukokeratosis in the proband |

|

| Figure 2: Pedigree of the family |

|

| Figure 3a: Mutation analysis of KRT6A – Wild type deoxyribonucleic acid sequence of exon 7 of KRT6A showing nucleotides c.1390-1404 |

|

| Figure 3b: Mutation analysis of KRT6A – The equivalent region as in (a) from the affected proband showing heterozygous mutation c.1397G>C leading to missense mutation p.Arg466Pro |

Historically, pachyonychia congenita was classified as pachyonychia congenita type 1 and type 2 but based on the extensive clinical and molecular data collected by the International Pachyonychia Congenita Research Registry, (http://registry.pachyonychia.org/s3/IPCRR) it was clear that there is an overlap between the subtypes. Therefore, the nomenclature was revised in 2011 based on the keratin mutation subtype.[1],[3], According to the revised nomenclature, those with mutations in KRT6A are named pachyonychia congenita-K6a, those with KRT16 mutations are pachyonychia congenita-K16, etc. Keratins are expressed in a tissue in a differentiation specific manner and as in other keratin disorders, pachyonychia congenita only affects sites where the mutant keratin protein is normally expressed. For example, K6a is normally expressed in palmoplantar epidermis, nail epithelia and mucosal tissues. To date (July 2016), the International Pachyonychia Congenita Research Registry has collected clinical and molecular data from 712 genetically confirmed cases of pachyonychia congenita worldwide. Pachyonychia congenita affects all ethnic backgrounds and there is no gender bias; males and females are equally affected. Of those enrolled in the International Pachyonychia Congenita Research Registry, 219 (31%) cases are spontaneous and 493 (69%), familial.

Pachyonychia Congenita Project provides a number of free services to pachyonychia congenita patients worldwide, who enroll in the International Pachyonychia Congenita Research Registry. This includes physician consultations, genetic testing and other support services. Genetic testing is performed using deoxyribonucleic acid samples extracted from saliva, rather than blood, collected in Oragene deoxyribonucleic acid sample collection kits supplied by the Pachyonychia Congenita Project. This makes sample collection and shipping easy, even for patients in remote areas.

There are a number of other very rare genetic skin disorders that share some clinical features with pachyonychia congenita and are caused by mutations in other genes; these include GJB6 (Clouston syndrome) and TRPV3 (Olmsted syndrome). Therefore, confirmation of the clinical diagnosis by genetic testing can be extremely important to ensure that patients receive appropriate genetic counseling and care. Currently, there is no specific treatment for pachyonychia congenita and patients typically pare/trim/file/grind their calluses and file/grind/clip their nails regularly.[4] Advice on caring for pachyonychia congenita and tools to use for trimming/clipping are available on the Pachyonychia Congenita Project website. However, there are a number of different therapeutic strategies being investigated to provide more specific and effective treatment.[5]

Here, we identified a previously unreported mutation in the 2B domain of KRT6A, thereby confirming the clinical diagnosis and adding to the expanding International Pachyonychia Congenita Research Registry database of clinical and molecular information, which will facilitate the development of future treatment and help to plan further clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank the family involved in this study. Thanks to the International Pachyonychia Congenita Consortium Genetics Team for useful discussions and Holly Evans of Pachyonychia Congenita Project for all her help with data preparation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Frances J. D. Smith and Neil J. Wilson were supported by a grant from the Pachyonychia Congenita Project (to Frances J. D. Smith, www.pachyonychia.org). The Centre for Dermatology and Genetic Medicine at the University of Dundee is supported by a Welcome Trust Strategic Award (098439/Z/12/Z to W.H.I.M.).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Eliason MJ, Leachman SA, Feng BJ, Schwartz ME, Hansen CD. A review of the clinical phenotype of 254 patients with genetically confirmed pachyonychia congenita. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:680-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Wilson NJ, O'Toole EA, Milstone LM, Hansen CD, Shepherd AA, Al-Asadi E, et al. The molecular genetic analysis of the expanding pachyonychia congenita case collection. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:343-55.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

McLean WH, Hansen CD, Eliason MJ, Smith FJ. The phenotypic and molecular genetic features of pachyonychia congenita. J Invest Dermatol 2011;131:1015-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Goldberg I, Fruchter D, Meilick A, Schwartz ME, Sprecher E. Best treatment practices for pachyonychia congenita. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28:279-85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

van Steensel MA, Coulombe PA, Kaspar RL, Milstone LM, McLean IW, Roop DR, et al. Report of the 10th Annual International Pachyonychia Congenita Consortium Meeting. J Invest Dermatol 2014;134:588-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,869

PDF downloads

2,768