Translate this page into:

The psychosocial impact of vitiligo in Indian patients

2 Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

M Ramam

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi

India

| How to cite this article: Pahwa P, Mehta M, Khaitan BK, Sharma VK, Ramam M. The psychosocial impact of vitiligo in Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013;79:679-685 |

Abstract

Background: Vitiligo has a special significance in Indian patients both because depigmentation is obvious on darker skin and the enormous stigma associated with the disease in the culture. Aims: This study was carried out to determine the beliefs about causation, aspects of the disease that cause concern, medical, and psychosocial needs of the patients, expectation from treatment and from the treating physician, and effects of disease on the patient's life. Methods: Semi-structured interviews were conducted in 50 patients with vitiligo. Purposive sampling was used to select subjects for the study. Each interview was recorded on an audio-cassette and transcripts were analyzed to identify significant issues and concerns. Results: Patients had a range of concerns regarding their disease such as physical appearance, progression of white patches onto exposed skin and the whole body, ostracism, social restriction, dietary restrictions, difficulty in getting jobs, and they considered it to be a significant barrier to getting married. The condition was perceived to be a serious illness. Stigma and suicidal ideation was reported. While there were several misconceptions about the cause of vitiligo, most patients did not think their disease was contagious, heritable or related to leprosy. Multiple medical consultations were frequent. Complete repigmentation was strongly desired, but a lesser degree of repigmentation was acceptable if progression of disease could be arrested. The problems were perceived to be more severe in women. The disease imposed a significant financial burden. Conclusion: Addressing psychosocial factors is an important aspect of the management of vitiligo, particularly in patients from communities where the disease is greatly stigmatizing.Introduction

Vitiligo has a special significance to patients in our country because depigmentation is obvious on dark skin and more importantly due to the enormous stigma that the disease carries. Studies using instruments that measure health related quality of life (QOL), such as the dermatology life quality index (DLQI), have shown that vitiligo affects QOL. [1],[2],[3] For example, a study in Indian patients showed that psychiatric morbidity manifesting as anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance occurs in a significant proportion of patients. [4] Other studies have documented the importance of physical appearance in psychological adjustment and the impact of the physical disfigurement caused by depigmentation. [5],[6] Vitiligo patients have a lower self-esteem as compared to the normal population. [7] Women with vitiligo experience greater QOL impairment than their male counterparts. [8] Vitiligo also has a psychosocial impact on children. [9] Studies using QOL and psychiatric morbidity questionnaires have shown prevalence of psychiatric morbidity (depressive episodes, adjustment disorders, anxiety) in 25% of patients with vitiligo. [10],[11] Many of these effects are produced by other disfiguring skin conditions and many concerns are shared by patients in other parts of the world, but a combination of individual, family and societal responses to vitiligo places a special burden on Indian patients with this disease.

Studies of the burden of vitiligo have commonly used pre-designed generic instruments and it is possible that some issues particularly important to patients with vitiligo may not have been captured. We were unable to find any detailed surveys on the perceptions about the disease and its effects in Indian patients. This study was carried out to determine the beliefs about causation, aspects of the disease that cause concern, medical and psychosocial needs of the patients, expectation from treatment and from the treating physician, effects of disease on the patient′s life and coping mechanisms used to deal with the illness.

In our study, information was elicited by conducting semi-structured interviews, a method that gives in-depth information about the patient′s psychosocial distress and allows an insight into the subject′s thoughts, feelings, and behavior. Recruitment for such qualitative studies use purposive sampling whereby patients who are able to express themselves and address a variety of issues are selected. [12] Such a study design has the advantage of being more dynamic as the interviewer learns from the patient′s response and may add questions or phrase the questions differently as the study progresses. It also allows for more diversity in responses from the patients. [13] Clearly, these studies provide information only on the patients studied, which may or may not be extrapolatable to the general population. Finally, qualitative studies are evaluated differently as compared to quantitative studies. Since, research questions tend to focus on what, how and why rather than whether or how much, the study is not interpreted or reported in numbers and percentages. [12]

Methods

Fifty patients attending the Out-patient Department of Dermatology of our large public hospital from November 2005 to October 2007 were interviewed. Most people who attend our clinic belong to the middle and lower socio-economic strata and hail mainly from the northern states of India. As we wanted to evaluate the psychosocial aspects of a wide range of patients with varying extent and onset of vitiligo, purposive sampling was used to select the subjects for the study. The patients comprised of young men and women, (both married and unmarried), children (>12 years), parents of children with vitiligo, elderly patients, patients with recent onset disease (<6 months) and those with long standing disease (>2 years), with limited vitiligo (<5%) and extensive vitiligo (>10%), patients with vitiligo on exposed areas, exclusively on covered areas and on the genitals. Patients who were willing and able to communicate their thoughts and feelings were interviewed. The interview was conducted in privacy in one of the consultation rooms in the dermatology clinic.

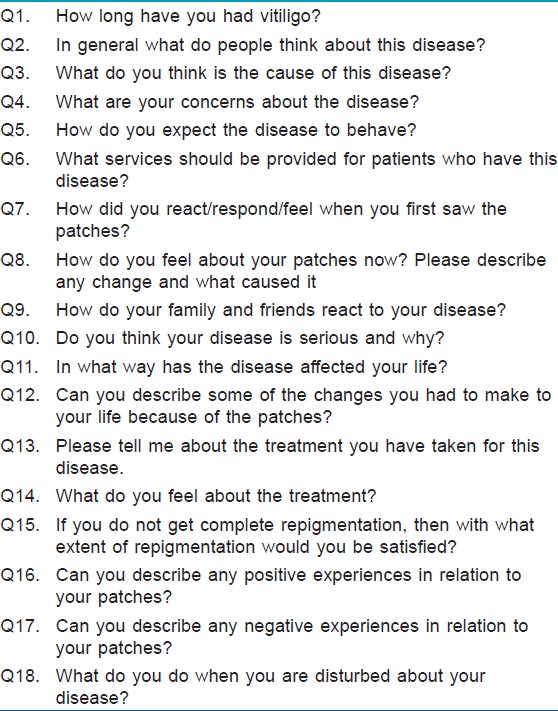

An interview guide was constructed on the basis of information obtained by review of literature and based on clinical experience. It consisted of questions regarding knowledge about the disease, psychosocial effects and coping mechanisms. Probes for follow-up questions were built into the interview guide to explore the issues raised by subjects. The draft guide was submitted to six experienced dermatologists and suggested modifications were incorporated. During the interview, the patient was given a chance to talk about his disease and additional information was obtained by asking relevant questions formulated in the interview guide. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at our institute.

Written informed consent to participate in this study and to have the interview recorded was obtained from patients and parents of children with vitiligo. Socio-demographic and clinical evaluation of the patient was recorded on a proforma. Forty six interviews were conducted in Hindi and 4 in English. Each interview lasted about 30-45 min. The interview was terminated when the patient had nothing further to say and questions in the interview guide had been covered [Table - 1]. Each interview was recorded on an audiocassette and later transcribed verbatim. Hindi scripts were then translated into English. Two of us independently reviewed the English transcripts.

A framework analytical approach was used for data analysis. This process involved the steps of familiarization with data, identification of themes, sorting through transcripts and identifying quotes, selection of particular quotes, and assigning them to themes/categories, mapping and final interpretation. The analysis was not strictly sequential with data being re-examined in the light of insights gained during the process. Data were examined line by line in order to identify the participants′ descriptions of thoughts, feelings, and actions related to the themes mentioned in the interviews. Once all the interviews were coded, data related to a common theme were put together and the following themes were identified: beliefs about vitiligo, impact of disease, concerns about the disease, treatment related issues, and coping mechanisms.

Results

Socio-demographic and clinical profile

A total of 50 patients were interviewed. The age of the patients ranged from 5 years to 75 years. There were 31 men and 19 women, of whom 16 males and 6 females were married. Five parents whose children had vitiligo were interviewed. Five patients were illiterate. Majority of the other patients had either completed matriculation or were graduates and 3 were post-graduates. The nature of occupation that patients were engaged in included: teaching, engineering, health-care, accountancy, marketing, farming, business, unskilled work, studies, and home-making. Incomes ranged from Rs. 300 to Rs. 60,000 per month in the employed; of the remainder, 20 patients were students, 4 were unemployed and 4 were housewives.

The duration of the disease ranged from 2 months to 52 years. Macules were increasing in size and new lesions were developing in 28 while in 22 patients, the disease was not progressive. The mental status examination of all patients was within normal limits.

The body surface involvement ranged from less than 1% to 95%. Thirty nine patients had involvement of the areas of the skin which were exposed. Eleven patients had involvement only of the unexposed sites. Twenty seven patients had involvement of the mucosal sites out of which the genitalia were involved in 18 patients. The clinical type of vitiligo the patients had were acrofacial (n = 25), vitiligo vulgaris (n = 10), focal vitiligo ( n = 2), segmental ( n = 2), acrofacial and vitiligo vulgaris ( n = 8), only mucosal ( n = 1) and universal vitiligo ( n = 2).

Interview analysis

The development of vitiligo was attributed to a deficiency in diet, reaction to medications, deficiency in the blood, decrease in melanin, physical trauma, problems in the intestines or liver, change in place (atmosphere and water), bacteria, recurrent cough and colds, God′s will, stress, and anger.

The disease was not considered contagious, heritable or related to leprosy by most patients though some thought it was and this led to stigmatization. Some patients stated that their friends and family held these mistaken beliefs; though they did not.

The first reaction of the patients on seeing their vitiligo was to ignore it. It was attributed by them to another illness such as allergy, dryness, leprosy, calcium deficiency, worms, fungal infections, burns, insect bites, and trauma.

Vitiligo was considered a serious illness in view of its possible adverse effects on marriage and securing a job, the undesirable appearance, stigma, bloating caused by medication, the lack of response to treatment, and the burning sensation on sun exposure. Those who said it was not serious stated that the disease was asymptomatic, not contagious, was at an early stage, was curable and was not leprosy and that nobody had responded adversely to the patches.

Dietary restrictions were frequently kept. Various foods were avoided such as sour items, non-vegetarian food, milk/curd, excess masala/chilli, alcohol, oil, food that was not home-cooked, sweets, rice, tea, wheat chapattis, green vegetables, a combination of non-vegetarian food and milk and salt on Sunday. Other restrictions that were undertaken included the wearing of synthetic and cotton clothes and plastic or rubber shoes. Patients wore clothes that covered their vitiligo.

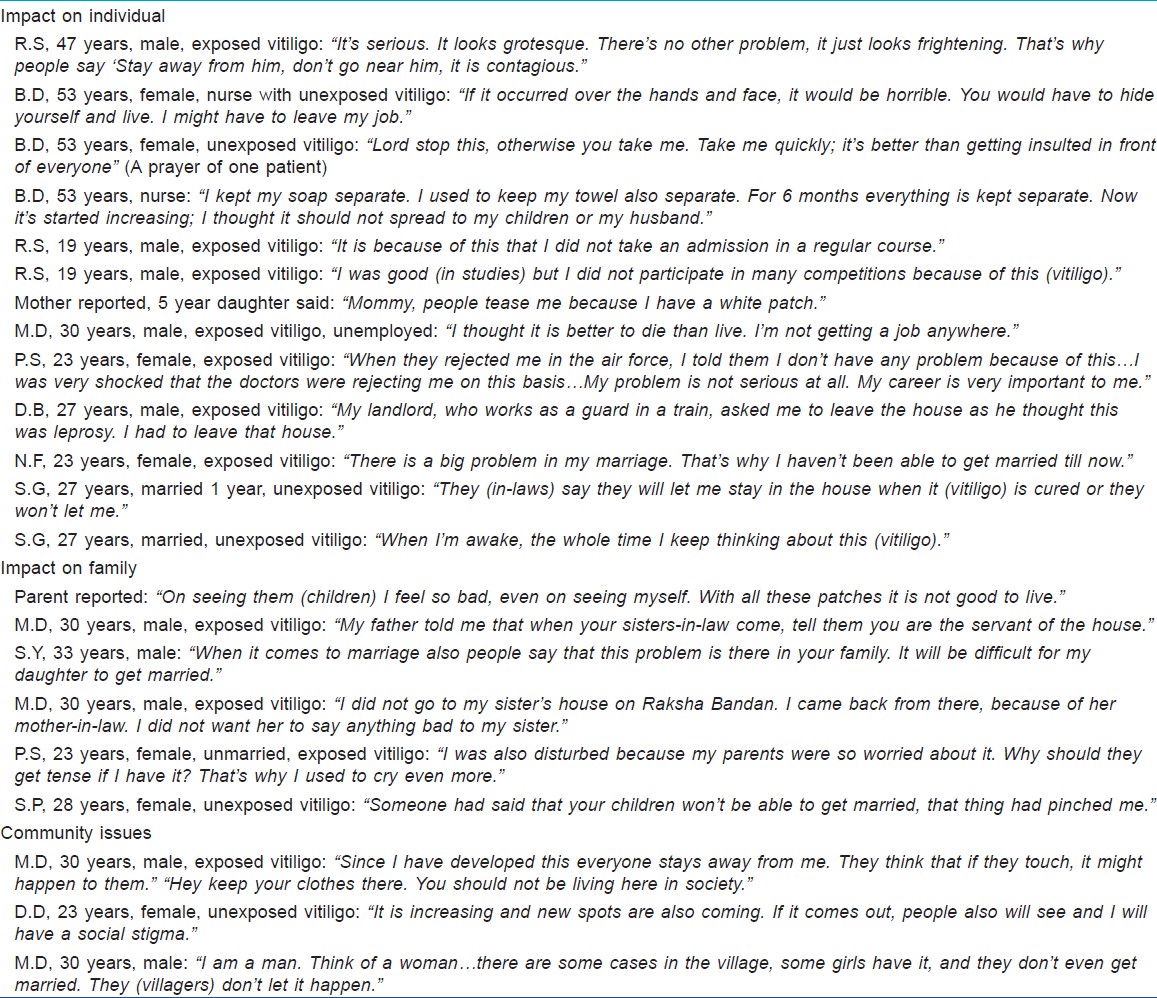

A wide variety of concerns were expressed with respect to the disease. Patients were unhappy with the way they now looked and this had seriously undermined the way they felt about themselves. The disease was a cause for worry, depression and low self-esteem. This worry lessened as time went by and they came to accept it. A few patients admitted to having had suicidal thoughts at times, but none had attempted suicide. Some patients thought about their vitiligo all day, some whenever they looked in the mirror and some not at all.

Parents of children with vitiligo thought about the disease all the time. They felt the disease would pose difficulties in getting the children married and that their child could develop an inferiority complex. Conversely, parental worry weighed on the minds of children; the disease was less of a concern than the parent′s anxiety and unhappiness.

Occasional problems faced in school or college were difficulty in participation in competitions in school, preferring a correspondence course to a regular course in college, having to leave school due to continuous visits to the doctors and being teased in school by other students.

Problems were uncommon at the workplace. A few people had difficulty in getting a job and were not allowed to join the careers of their choice including, defence services, civil services, air force, and courier services. It was disheartening to have to look for other careers on account of the disease.

Unmarried patients anticipated difficulties in getting married, women more than men. This was a special problem in villages. One man said that he had been rejected in four marriage proposals. One patient with vitiligo limited to the face and extremities was being compelled by his parents to get married for fear that his vitiligo would spread all over and mar his prospects of marriage if they delayed.

The disease was not revealed to the partner at the time of marriage due to embarrassment or the fear of rejection. It was also considered sexually transmissible. One patient had been rejected by her in-laws and told to get divorced if not cured. A woman who had vitiligo on the breast had problems as her husband was uncomfortable during sexual intercourse.

Another important concern was the possible progression of the disease. Patients with vitiligo on the covered areas of the body were worried it would go on to involve skin visible to others.

Other concerns expressed were development of white hair in the macules, the inability to wear sleeveless clothes, and being subjected to pity.

A majority of patients received adequate support from their family members including moral support, money for treatment and being accompanied by family members on visits to the doctor. This was a great comfort to them. However, patients carried a burden of guilt and fear that their disease could spread to others in the family or affect the prospects of marriage of other family members.

A few patients who had vitiligo on the exposed areas had stopped attending social functions and meeting people as they were ashamed of their disease. They were teased by children and avoided shaking hands with other people. They had difficulty with or were tired of answering queries. One man was abused as a leper and cast out of his village. One patient did not visit his sister as he thought she would be ostracized by her in-laws if they discovered she had a brother with vitiligo. Two patients, one male and one female had been told to live separately from their spouses and another was separated from her brothers and sisters because her parents thought vitiligo was contagious. Those who had vitiligo on covered areas had no difficulty in social interaction.

Patients had sought alternative medicine and visited homeopaths, Ayurvedic doctors and practitioners of other systems of indigenous medicine in the past. These were believed not to cause side effects. Dietary and life-style restrictions were often prescribed by alternative medicine practitioners and even by allopathic doctors including dermatologists. In a few cases, the vitiligo had been mistaken and treated for leprosy.

Vitiligo also causes a financial burden. Numerous doctors were consulted for treatment the largest number reported being 20. Patients reporting for the first time for consultation were relatively unaware about the disease and had fewer misconceptions than those who had had it for a long period of time and had spoken to others about the illness.

Treatment issues

Patients wanted complete repigmentation. On being asked what degree of improvement was acceptable if complete repigmentation was not possible, many patients said they would be satisfied if patches did not progress further to other areas or if it did not involve the exposed areas. Repigmentation of patches on exposed skin (e.g. on the hands or feet) and varying degrees of repigmentation were desired. Some would not be happy unless they had complete repigmentation. Those who were older than 50 years and whose children were married were comfortable without any treatment.

Coping mechanisms

Different types of coping mechanisms were used when patients thought about their disease. Patients resorted to praying to God or distracted their mind with music, television, books, playing games or doing their work. Other mechanisms were talking to their family members, friends or doctor or trying to find a cure by reading books. Patients with poor coping mechanisms expressed emotional reactions in the form of crying, avoiding company, were constantly preoccupied with the disease, took alcohol daily to forget and had suicidal thoughts.

Discussion

Our study indicates the diverse ways in which vitiligo affects the lives of Indian patients. In spite of different educational and occupational backgrounds, the concerns and beliefs in patients were similar and misconceptions about vitiligo were prevalent amongst people of all social strata [Table - 2]. Patients from rural areas experienced greater problems with ostracism and marriage probably due to closer social grouping in villages.

Apart from suffering the stigma of vitiligo, patients also had guilt about the stigma that attached to other unaffected members of the family because of their disease. Previous studies have noted lowered self-esteem in patients with vitiligo [7] while those who coped well with their disfigurement were found to have higher self-esteem. [6]

The severity of the psycho-social impact is indicated by the fact that some patients thought about their disease all day and could not bear to look at themselves in the mirror even when covered areas alone were affected. A previous questionnaire and interview based study of 326 patients with vitiligo in a hospital-based out-patient setting indicated that two-thirds felt worried about the spread of disease, whether their children would inherit the disease and whether new cures would be found. Over half said that people stared at them, and from 20% to 25% said that they had been the victim of snide remarks by strangers. [6],[14] In a previous study of 30 patients from India, 10% patients were found to have depression, one patient had anxiety and one patient had suicidal ideation. [4]

Concern that the disease could spread to involve the whole body was an important reason for seeking treatment. The psychosocial impact on education, marriage, and employment was felt most by young adults. In older patients, the social price of vitiligo in the family to be paid by unaffected younger family members was a major concern. Vitiligo had an impact on the choice of career with some jobs being denied to patients. On the other hand, the development of vitiligo after employment had been secured had fewer effects. An area of major impact is marriage with difficulties in getting married. Even after marriage, vitiligo continued to exert its influence leading to difficulties with in-laws, sexual relations, and even resulting in divorce. Patients also faced the burden of unsolicited advice and intrusive questioning from family members, peers, friends and well-wishers.

In a study by Ongenae et al., [3] vitiligo moderately affecting head, face or neck areas, trunk and feet localizations were found to correlate significantly with the overall DLQI score. Vitiligo on the exposed areas in a few of our patients caused problems in social interaction though most patients claimed to be unaffected. Patients with vitiligo in the covered areas were less concerned about social interaction and functioning, but were quite worried about the social consequences of vitiligo spreading to the exposed areas.

Patients who visited their dermatologist about their disease often had higher DLQI scores. [3] However, disease location, severity, and visibility were found to be independent of the number of consultations in the same study. [3] In our study, quick treatment results were desired resulting in multiple consultations and willingness to spend large amounts of money. Treatment was expected to result in complete regimentation failing which it was expected to at least arrest the progression of the disease. Patients frequently changed their doctors because of impatience with the slow response, due to lack of information about the need for prolonged therapy or in spite of it. Dietary restrictions were believed to play an important role in therapy by patients, their family members and medical practitioners.

There was a tendency to be less troubled by the disease with passing time, but this was not an irreversible change of attitude. For example, patients who were unconcerned and did not seek treatment became troubled by the disease when they were disqualified for employment on medical grounds because of vitiligo.

Coping responses are related to the level of self-esteem. Those patients with positive self-image are able to cope better with physical disabilities. [15] Patients who had poor coping mechanisms were more disturbed about their disease than those who had other types of coping mechanisms. This has implications in the management as these patients need to be taught coping skills in addition to treatment of the white patches.

A limitation of our study is that purposive sampling was utilized hence the results may not be applicable to all patients who have vitiligo; however, the observations made in this study have important implications for the management of vitiligo. Evaluation of psychological and social factors in addition to the primary dermatological condition is as relevant to vitiligo and perhaps more so than in other skin disease. [16] Interestingly, patients with greater impairment of quality of life were found to respond less favorably to treatment. [17] In evaluating the psychological impact of vitiligo, it is also important to consider the patient′s life situation including social support network and the attitude of colleagues, and family members as even "mild" disease may greatly distress the patient. Psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy are helpful in improving body image, self-esteem and QOL of patients with vitiligo and also appear to have a positive effect on the course of the disease. [18] Apart from individual interventions, support and self-help groups may help people deal with this psychologically and socially devastating disease.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Shuba Kumar for unflagging support of this study at all stages: from conception to publication.

| 1. |

Kent G, al-Abadie M. Factors affecting responses on Dermatology Life Quality Index items among vitiligo sufferers. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996;21:330-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Belhadjali H, Amri M, Mecheri A, Doarika A, Khorchani H, Youssef M, et al. Vitiligo and quality of life: A case-control study. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2007;134:233-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Ongenae K, Van Geel N, De Schepper S, Naeyaert JM. Effect of vitiligo on self-reported health-related quality of life. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:1165-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Sharma N, Koranne RV, Singh RK. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis and vitiligo: A comparative study. J Dermatol 2001;28:419-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Firooz A, Bouzari N, Fallah N, Ghazisaidi B, Firoozabadi MR, Dowlati Y. What patients with vitiligo believe about their condition. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:811-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Porter J, Beuf AH, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Psychological reaction to chronic skin disorders: A study of patients with vitiligo. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1979;1:73-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Porter JR, Beuf AH, Lerner A, Nordlund J. Psychosocial effect of vitiligo: A comparison of vitiligo patients with "normal" control subjects, with psoriasis patients, and with patients with other pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15:220-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Borimnejad L, Parsa Yekta Z, Nikbakht-Nasrabadi A, Firooz A. Quality of life with vitiligo: Comparison of male and female muslim patients in Iran. Gend Med 2006;3:124-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Hill-Beuf A, Porter JD. Children coping with impaired appearance: Social and psychologic influences. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1984;6:294-301.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Mattoo SK, Handa S, Kaur I, Gupta N, Malhotra R. Psychiatric morbidity in vitiligo: Prevalence and correlates in India. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2002;16:573-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Mattoo SK, Handa S, Kaur I, Gupta N, Malhotra R. Psychiatric morbidity in vitiligo and psoriasis: A comparative study from India. J Dermatol 2001;28:424-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 2000;284:357-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: What are they and why use them? Health Serv Res 1999;34:1101-18.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Porter J, Beuf AH, Lerner A, Nordlund J. Response to cosmetic disfigurement: Patients with vitiligo. Cutis 1987;39:493-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Porter J. The psychological effects of vitiligo: Response to impaired appearance. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ, editors. Vitiligo a Monograph on the Basic and Clinical Science. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd.; 2000. p. 97-100.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Psychiatric and psychological co-morbidity in patients with dermatologic disorders: Epidemiology and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4:833-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Parsad D, Pandhi R, Dogra S, Kanwar AJ, Kumar B. Dermatology Life Quality Index score in vitiligo and its impact on the treatment outcome. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:373-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Papadopoulos L, Bor R, Legg C. Coping with the disfiguring effects of vitiligo: A preliminary investigation into the effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy. Br J Med Psychol 1999;72:385-96.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

12,891

PDF downloads

2,311