Translate this page into:

A clinicoepidemiological study of polymorphic light eruption

Correspondence Address:

Lata Sharma

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi -221 005

India

| How to cite this article: Sharma L, Basnet A. A clinicoepidemiological study of polymorphic light eruption. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:15-17 |

Abstract

Background and Aims: The prevalence of polymorphic light eruption (PLE) varies between 10-20% in different countries but no such data is available from India, where exposure to sunlight is high. Methods: A clinico-epidemiological study of PLE was done in the skin outpatient department (OPD) of Institute of Medical Sciences Hospital from January to December. Results: The ages of the patients varied from 5-70 years. Out of a total of 39,112 OPD cases, 220 cases of PLE (138 females and 82 males) were recorded, giving a prevalence of 0.56% in this study population. The skin type varied between IV and VI in 96% of the cases. Housewives were 81, students 67, office persons 39, farmers 22, businessmen 6 and unemployed 5. Discussion: The manifestation of PLE was most common in housewives in areas exposed to the sun. Most of the PLE patients presented with mild symptoms and rash around the neck, forearms and arms which was aggravated on exposure to sunlight. PLE was more prevalent in the months of March and September and the disease was recurrent in 31.36% of the cases. Conclusions: The prevalence of PLE was 0.56%. It was mild in nature and only areas exposed to the sun were involved.

Introduction

Polymorphic Light Eruption is an abnormal cutaneous response which occurs on exposure to sunlight. The reported prevalence in various cohort studies from England, Sweden and Singapore varies from 10-20% and 26% in a study by Fotiades et al. [1],[2],[3],[4],[5] No such data however, is available from our country even though the exposure to sunlight is high.

Methods

A clinico-epidemiological study was done in patients who had been visiting our Dermatology OPD for a period of one year. Subjects taking systemic corticosteroids or photosensitizing drugs were excluded. Thus, 220 cases of PLE were registered from January to December. Patient details recorded included month and age of onset of symptoms of PLE, its severity, nature - transient, persistent or recurrent, aggravating factors, constitutional and other symptoms, results of healing of the rash and any change in the severity of symptoms. History of the disease in the family, the patient′s profession, duration of exposure to sunlight during outdoor activities including travel, preference for the type of clothing; materials used during daytime - cosmetics and sunscreens, as well as types of previous treatments were noted.

Findings of the clinical examination were recorded including the skin type of cases as classified by the Fitzpatricks skin phototype scale. [6] Details of skin lesions and the site, size, shape, color, type and secondary changes were noted. In doubtful cases, patients were asked to protect the affected part from sun exposure for 7-10 days during which the lesions of PLE should have healed without scarring. Immunological and urine examinations were done to exclude systemic lupus erythematosus and porphyria. Data thus obtained was compiled, tabulated and statistically summarized.

Results

Out of the total 39,112 patients who attended the Dermatology OPD, 220 patients had PLE. The prevalence of PLE was thus calculated to be 0.56%, which included 138 females and 82 males. The age of the patients varied from 5 to 70 years with mean ± standard deviation of 29.90 ± 12.22 years. The ages of 131 (59.55%) cases were ≤ 30 years and the ages of 76 (34.54%) cases were between 31 and 50 years.

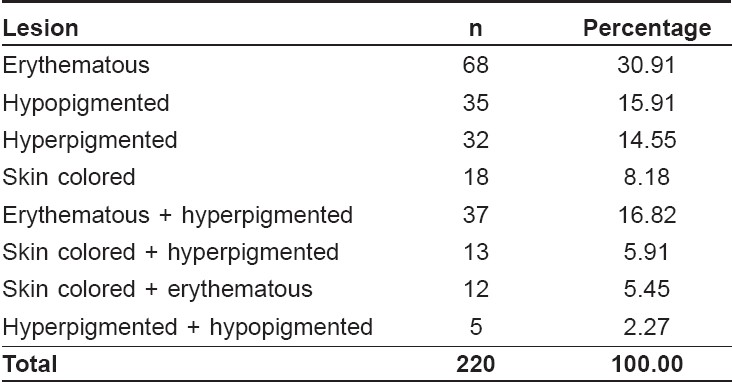

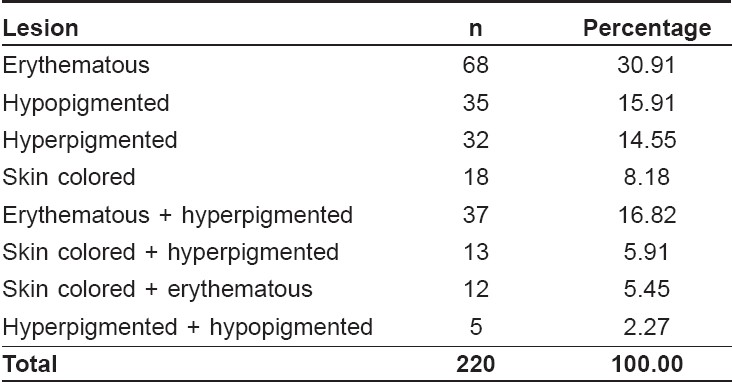

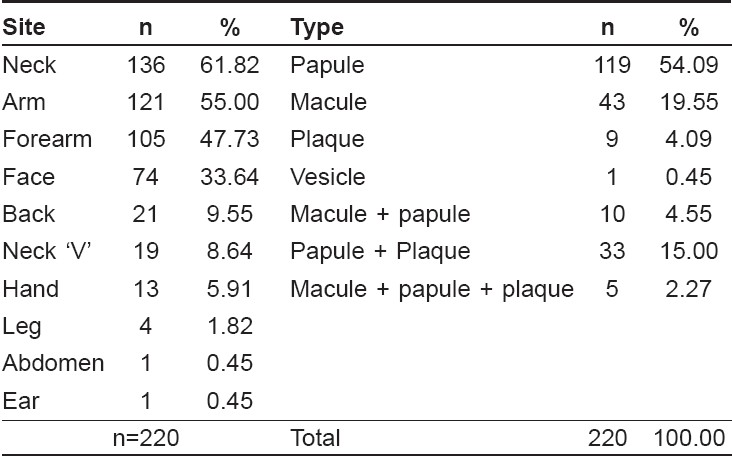

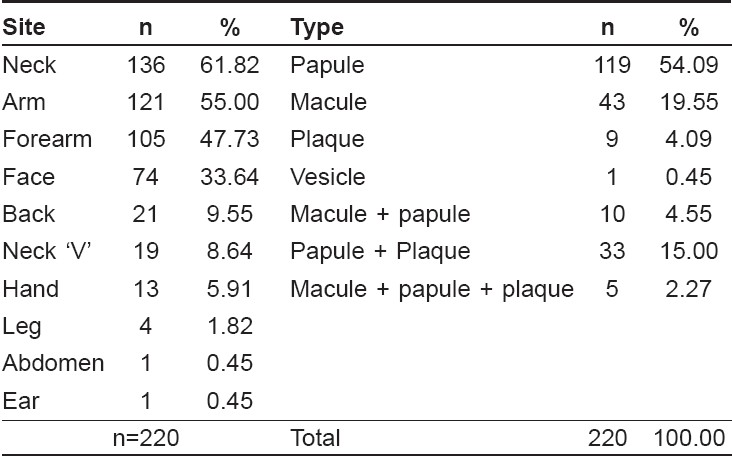

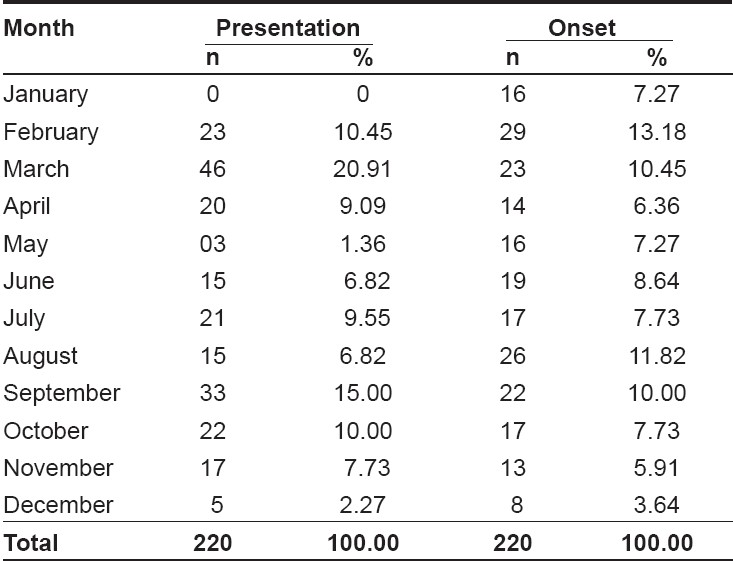

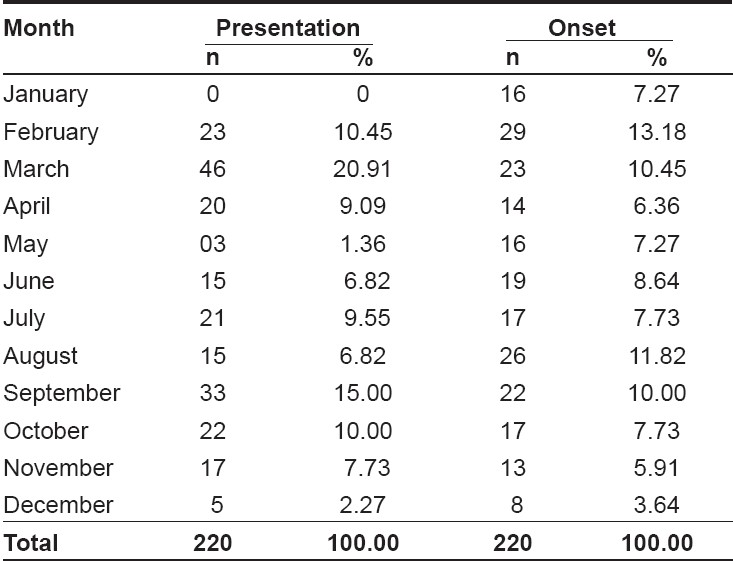

Eighty one cases were housewives, 67 were students 39 were office persons, 22 were farmers, 6 businessmen and 5 were unemployed. Skin rash was present in all cases along with itching in 151, burning sensation in 20, both itching and burning in 13 while 36 were asymptomatic. Constitutional symptoms like fever and malaise were present in 11 cases, headache in 3 and swelling of the face in 1. The rash appeared on exposure to sunlight within 30 minutes in 65 cases and after > 30 minutes in 20 cases, on termination of exposure in 20 but the time interval was not known in 115 patients. The aggravating factor was sunlight in 103 cases, the heat of an open fire while cooking food in 6, unidentifiable in 69 cases and both sunlight and heat in 42 cases. The month of onset of rash varied from January to December. The months of presentation were March and September for 46 and 33 cases, respectively [Table - 1]. There was history of recurrence in 99 cases, severity of rash increased in 69, decreased in 23 and no change was noted in 7 cases. History of atopy was present in 5 cases and in family in 23 cases. History of PLE was present in family in 22 cases including 2 each in the grandfather, father, brother and son, in the mother in 6 and in the sister in 8 cases. The material of clothing used was of a mixed type in 172 cases, cotton in 35 and synthetic in 13. In the history of treatment, 40 patients used a topical steroid, 24 antifungal, 13 sunscreens, 4 oral steroids, 19 antihistaminic, and eight used homeopathic drugs. The skin type of patients varied from III to VI with a maximum of 107 (48.64%) cases in type IV, 72 (32.73%) in V, 33 (15%) in VI and only 1 (0.45%) in type I. Exposed parts were involved in all cases. The rash was papular in most of the cases [Table - 2]. The majority of the lesions were erythematous [Table - 3]. Acne was associated in 42 patients, melasma in 11 and tinea corporis in 7 patients.

Discussion

PLE is considered to be a disease of fair-skinned individuals with skin types I to IV. [2] It is less common in very dark-skinned individuals in America, India and Pakistan. [7] In our study, 96% of the patients were of skin types IV to VI which explains its low prevalence (0.56%). The majority of the cases were in the age group of 21-30 years consistent with the existing idea that PLE is a disease of the first three decades of life. [8] Of the cases suffering from PLE, 62.73% were females. Most of them were housewives in whom exposure to sunlight was intermittent and for a short period. The clothing used was light which gave full exposure to the neck, arms and forearms. Partial ultraviolet radiation-induced immunosuppression is said to result in a delayed type hypersensitivity response to photoinduced antigens. [9] PLE lesions fade off near or sometimes sharply at the borders of garments but not all exposed areas are involved. It is thought that exposure of those areas throughout the year makes them more tolerant. [10] The onset of PLE was in the months of February and August in 13.18 and 11.82% of the cases, respectively. In March and September, 20.91 and 15% of the cases were recorded which was high when compared to the other months. During these months, patients used light clothing with short sleeves during outdoor activity. This is the time when the sun shines on the equator and the days and nights are of almost equal length. Hawk has described PLE as a disease of the spring when moderate intensity of sunlight causes maximum hazard. [11] The action spectrum of PLE is said to include both long and short wavelength ultraviolet radiation but in a study by Pryzbilla and co-workers, all cases tested were negative for a ultraviolet B photopatch test. [8]

The majority of the cases were from the city of Varanasi where the study was conducted. Its latitude is 25 o north and longitude 83° east. The prevalence of PLE is said to be higher in regions away from the equator because of the variation in the proportion of ultraviolet A and B radiations at different latitudes. [5] Sunlight was the precipitating factor in 46.82% of the cases, the heat of an open fire in 2.73%, both of these in 19.09% although the precipitating factor was not known in 31.36% of the cases. Consistent with a report by Jansen, we found that a 30 min exposure to sunlight was required to produce the rash, the interval being slightly less than ½ hour in 29.55% of cases, more than ½ hour in 9.09%, but 52.27% were not aware of this. [12]

The external aspect of the arms and forearms were involved in most of the cases possibly because these parts are placed horizontally while sitting or traveling and receive the maximum exposure. On the other hand, the position of the face is vertical while walking or working or it may not even be exposed to the sun if the person is bending forward. The exposure of covered areas in the summer months makes them vulnerable to this photodermatosis. [13] The decline in the severity of eruption or rash on repeated sun exposure or as summer progresses, causes the observed hardening. [12] The rash was recurrent in 99 cases but an increase in the severity of lesions was noted by 23 cases. It appears that the disease did not manifest fully in the beginning. The type of lesion was papular or macular in this study as compared to the vesicular and plaque types and extensive involvement as reported by Hawk. [11] Fewer cases had itching, burning and constitutional symptoms than reported by Frain-Bell et al . [8] It may be because the disease was milder in this part of the world. Covered areas were not affected irrespective of the type of clothing or weave tightness which suggests that it is probably preventable by all types of clothing. [12] Inheritance of PLE is probably polygenic or through a dominant single gene. [13] Family history of PLE was found in 10% of the cases in the present study but varied from 6.25-12% in the studies conducted by Ross [2] and Millard. [13] As it is a mild photodermatosis in India, many patients were not aware of its occurrence in other members of the family.

| 1. |

Morison WL, Stern RS. Polymorphous light eruption: A common reaction uncommonly recognized. Acta Derm Venereol 1982;62:237-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Ros AM, Wennersten G. Current aspects of Polymorphous light eruptions in Sweden. Photodermatol 1986;3:298-302.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Khoo SW, Tay YK, Tham SN. Photodermatoses in a Singapore skin referral centre. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996;21:263-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Pao C, Norris PG, Corbett M, Hawk JL. Polymorphic light eruption: Prevalence in Australia and England. Br J Dermatol 1994;130:62-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Fotiades J. Soter NA, Lum HW. Result of evaluation of 203 patients for photosensitivity in 3 years period. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33:597-602.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun reactive skin type I through VI. Arch Dermatol 1988;124:869.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Magnus, IA. Dermatological photobiology: Clinical and experimental aspects. Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford; 1976. p. 117-63.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Frain-Bell W, Dickson A, Herd J, Sturrock I. The action spectrum in polymorphic light eruption. Br J Dermatol 1973;89:243.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Palmer RA, Fredman PS. Ultraviolet radiation causes less immunosuppression in patients with polymorphic light eruption than in controls. J Invest Dermatol 2004;122:291-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Ting WW, Vest CD, Sontheimer R. Practical and experimental consideration of sun protection in dermatology. Int J Dermatol 2003;42:505-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Hawk JLM, Norris PG. Abnormal responses to ultraviolet radiation. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors, Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. McGraw-Hill: New York; 1999. p. 1:1573-89.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Jansen CT. The Natural history of Polymorphous light eruptions. Arch Dermatol 1979;115:165-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Millard TP, Bataille V, Snieder H, Spector TD, McGregor JM. The heritability of polymorphic light eruption. J Invest Dermatol 2000;115:467-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,721

PDF downloads

3,399