Translate this page into:

A combination of oral azathioprine and methotrexate in difficult to treat dermatoses

Corresponding Author:

Puneet Agarwal

397, Shree Gopal Nagar, Gopalpura Bypass, Jaipur, Rajasthan

India

dr.puneet09@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Agarwal P, Agarwal US, Meena RS, Sharma P. A combination of oral azathioprine and methotrexate in difficult to treat dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:389-392 |

Sir,

In dermatology, many patients suffer from chronic inflammatory diseases which include phytophotodermatitis, chronic actinic dermatitis, endogenous dermatitis and autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, autoimmune blistering disorders and neutrophilic dermatoses such as pyoderma gangrenosum, Behcet's disease and vasculitis. The mainstay of treatment for these patients remains topical and oral corticosteroids with or without oral steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents, mainly methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide and others. However, in some cases, these agents are unable to achieve an effective immunosuppression, so it is difficult to control the disease without high doses of oral corticosteroids. The option then available is either to increase the dose of immunosuppressive which is limited by adverse effects or changing the immunosuppressive. If changing the immunosuppressive is not effective, it is quite difficult to control the disease as long-term high-dose oral corticosteroids have adverse effects. Furthermore, in patients of exogenous dermatitis, such as chronic actinic dermatitis and phytophotodermatitis, it is difficult for patient to avoid the causative factor which leads to aggravation of symptoms. Thus, for these difficult to treat patients, an additional therapeutic tool is required to control their disease.

A combination of immunosuppressives is not new and is used to control acute exacerbations of disease. Although these combinations are effective for acute control, their long term continuation is not possible due to adverse effects as well as cost.

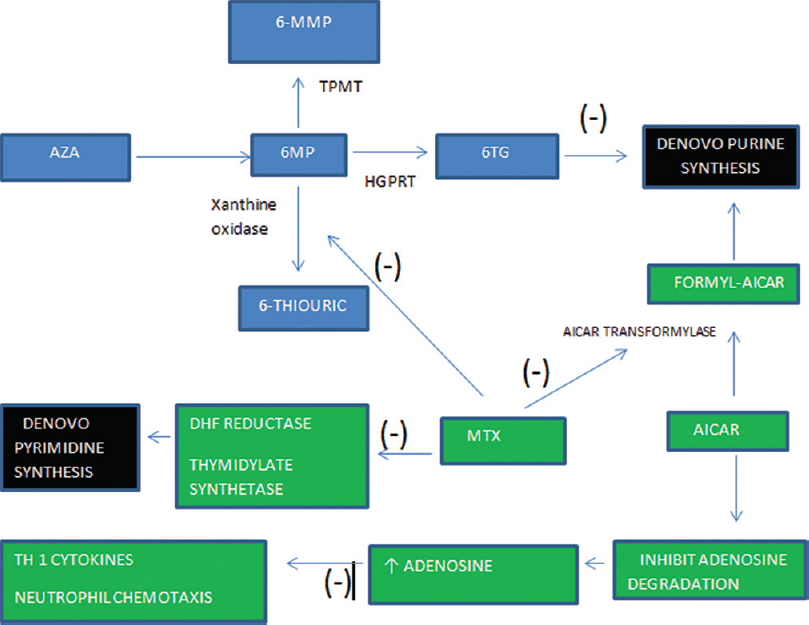

Out of the available combinations, azathioprine and methotrexate seems to be a good option as: (1) both drugs have a good safety profile and are frequently used individually for long term, (2) methotrexate inhibits xanthine oxidase and increases the amount of active metabolites of azathioprine and might lead to an enhanced immunosuppression [Figure - 1], (3) both drugs are easy to monitor for adverse effects, (4) both are cheap. On reviewing literature, we came across some articles where a combination of azathioprine and methotrexate was used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (which is also a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder). In these studies, this combination was used in a large number of patients for a long-term without any severe adverse effect.[1],[2],[3] Thus, we decided to use this combination therapy along with oral corticosteroid in our difficult to treat patients who were not being controlled by single immunosuppressive agent. We found that among combination of steroid-sparing agents, use of methotrexate-azathioprine combination has not yet been reported in literature for any dermatologic indication. Here is a brief summary of our cases.

|

| Figure 1: Azathioprine is absorbed in gastrointestinal tract and undergoes nonenzymatic conversion to 6-mercaptopurine. 6-mercaptopurine is oxidized by xanthine oxidase to 6-thiouric acid, methylated by thiopurine methyltransferase to form 6-methyl-mercaptopurine and converted to 6-thioguanine nucleotides by hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase. 6-thiouric acid and 6-methyl-mercaptopurine are both inactive metabolites while 6-thioguaninenucleotides are active metabolites that inhibit the de novo synthesis of purines and are incorporated into DNA as a false base which triggers cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Methotrexate inhibits xanthine oxidase and increases 6-thioguaninenucleotides concentration, hence, enhancing azathioprine efficacy. Furthermore, methotrexate inhibits pyrimidine synthesis enhancing the suppression of DNA synthesis in lymphocytes. Methotrexate inhibits 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase which catalyzes one of the final stages of de novo purine synthesis. Inhibition of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase leads to increased levels of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide which results in increase intra- and extra-cellular adenosine. Adenosine is a purine nucleoside that has been shown to have potent anti-inflammatory by inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis and suppressing Th1 cytokines |

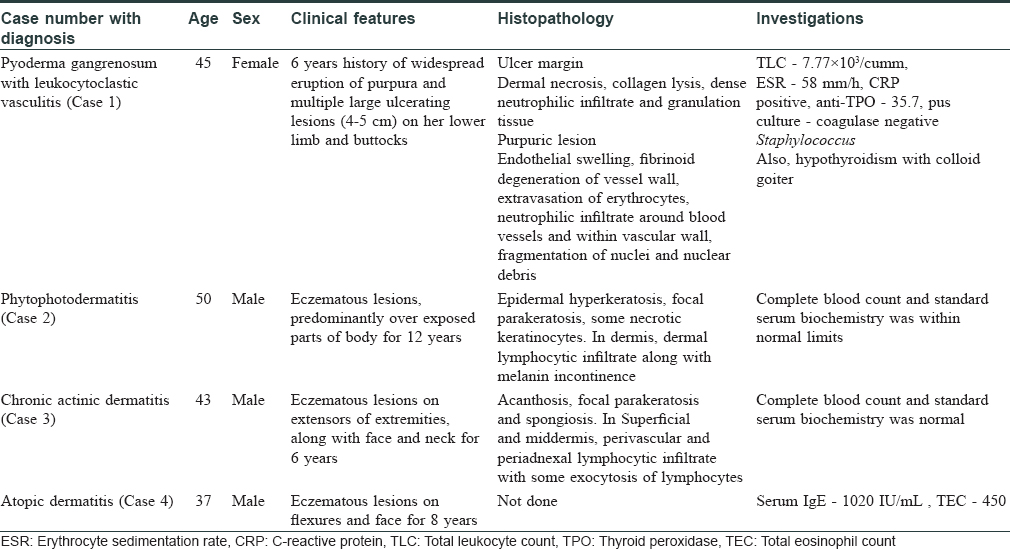

A total of four patients, three men and one woman with chronic inflammatory dermatoses, whose disease activity was not controlled by high-dose oral corticosteroids along with a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive, were treated with a combination of oral azathioprine (50 mg BD) and methotrexate (15 mg/week) along with oral corticosteroids. The dose of corticosteroids, azathioprine and methotrexate, was tapered gradually according to response of disease activity so as to control the disease without any oral corticosteroid. Baseline investigations were done in all cases which included complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, fasting blood sugar, renal function test, liver function test and chest X-ray. All the patients were regularly monitored for side effects, every 1 week for 1st month of initiating the treatment followed by every 2 weeks for next 2 months and then monthly. They were observed for 40 weeks.

The clinical details of the cases have been briefed in [Table - 1] and treatment has been described below.

Case 1

The patient was admitted in November 2015 and was initially treated with oral prednisolone 40 mg/day along with oral cyclosporine 100 mg BD. She responded to treatment and there was a decrease in inflammation and the progression of ulcers stopped. Cyclosporine was tapered gradually to up to 25 mg BD after 17 weeks and prednisolone to 10 mg/day. After 9 months of treatment, the patient came with a fresh episode of multiple, severely painful new ulcers and less symptomatic purpuric eruptions. She was then admitted again, the dose of cyclosporine was increased to 100 mg BD along with 40 mg prednisolone. There was a slow healing of ulcers and new lesions continued to appear. Thus, along with cyclosporine, azathioprine was added at 100 mg/day. However, before any response could be obtained the patient developed hypertension and cyclosporine had to be withdrawn. Due to the severity of disease and large size of ulcers, methotrexate was added in a dose of 15 mg/week along with azathioprine 100 mg/day.

Case 2

The patient was taking oral corticosteroids for a long duration, so he was treated with oral prednisolone 40 mg/day and oral methotrexate 15 mg/week along with topical emollient and topical steroids with strict instructions to cover exposed parts. He was given oral corticosteroids as 40 mg/day for a week and then tapered gradually by 10 mg every week. The methotrexate continued at 15 mg/week. He responded to the treatment and his lesions began to decrease. After 4 weeks, when the dose of oral corticosteroids was tapered to 10 mg/day, the disease flared up and dose had to be increased to 30 mg/day. It was decided to change the immunosuppressive to azathioprine at 100 mg/day. The oral corticosteroids were tapered to 10 mg/week. However, again, an exacerbation was seen at the end of 4 weeks.

Case 3

This patient again was on oral corticosteroids for a long term. He was started with same protocol as followed in case 2 with strict photoprotection but was difficult to control when dose of oral corticosteroids was tapered at the end of 8 weeks.

Case 4

He also did not respond to high dose of oral corticosteroids and methotrexate as well as of azathioprine as in case 2 and 3.

All these patients, refractory to treatment with single immunosuppressive and high dose of oral steroids, were started with a combination of azathioprine (50 mg) BD and methotrexate 15 mg/week along with oral prednisolone, 30–50 mg/day. Baseline investigations were done in all cases.

In case 1, after 25 days of treatment, there was a significant reduction in inflammation and exudation along with rapid decrease in further progression of ulcers. In the next 10 weeks, the ulcers healed completely and there was no new lesion. The dose of azathioprine and methotrexate were then tapered to azathioprine 50 mg/day and methotrexate 7.5 mg/week. The dose of oral prednisolone was tapered to a maintenance dose of 5 mg/day. In the following weeks, no new lesions were seen until 40 weeks of treatment.

In the rest of the cases, there was a reduction in severity and number of lesions in 8–10 weeks. After 10–12 weeks of treatment with combination of azathioprine and methotrexate, it was possible to reduce the dose of oral corticosteroids to as low as 5 mg/day without any exacerbation of symptoms. Then, the dose of immunosuppressive agents was also tapered, after the disease activity was effectively controlled, i.e., after almost 15 weeks. Azathioprine was tapered to 50 mg/day and methotrexate to 7.5 mg/week. In the following weeks, the patients required an intermittent escalation of dose of oral prednisolone, but it was as low as 10–15 mg/day and could be effectively tapered rapidly in 2–3 weeks to 5 mg/day. An escalation in dose of azathioprine and methotrexate was also required in one case.

No adverse effects were noted in all these patients at the end of 40 weeks.

Azathioprine and methotrexate have been used in combination to control severe rheumatoid arthritis. In a study of 212 patients of rheumatoid arthritis by Willkens et al., a combination therapy of methotrexate (5–7.5 mg/week) and azathioprine (50–100 mg/day) was compared with these drugs given as monotherapy and the results were observed at 24 and 48 weeks.[1],[2] At the end of 24 weeks, it was concluded that the combination therapy was not statistically superior to methotrexate therapy alone, but both combination therapy and methotrexate alone were superior to azathioprine alone when patients were analyzed by intent-to-treat and withdrawals treated as treatment failures. If only patients who continued taking the therapy were analyzed, the mean improvement was greater for azathioprine therapy then for methotrexate while combination remained the most active. The most frequent adverse effects observed were gastrointestinal adverse effects or the elevation of liver enzymes. At 48 weeks, it was observed that the combination of methotrexate and azathioprine in the dosage utilized was not associated with more toxicity than treatment with single agents; however, enhanced efficacy was also not seen.

Brio et al. reported the use of methotrexate, azathioprine and hydroxychloroquine therapy in twenty rheumatoid arthritis patients for a mean duration of 14.7 months.[3] Seventeen out of twenty patients experienced marked improvement in mean erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mean grip strength and mean joint count of tender or swollen joints. In this study, a single patient discontinued therapy due to stomatitis.

Multiple drugs act synergistically at multiple points in the cascade of inflammation. The theoretical advantage of combination therapy is an enhancement of overall efficacy due to different mechanisms of action and the lower doses of individual drugs as well as concomitantly lower frequency of adverse effects.[4] The combinations may also modify toxic effects by enhancing hepatic metabolism or by some as-yet-unclear mechanisms.

Both azathioprine and methotrexate are antimetabolites and act on proliferating T and B cells which are more sensitive than nonimmune cells to the depletion of purines and pyrimidines.[5] Methotrexate provides rapid induction of improvement while it takes 4–6 week for azathioprine to act. Hence, administering methotrexate with azathioprine provides better patient compliance due to its prompt action.

Moreover, methotrexate and azathioprine have been found to have some synergistic action in their mechanism of immunosuppression [Figure - 1].[6] Azathioprine enters the bloodstream and undergoes nonenzymatic conversion to 6-mercaptopurine by compounds with sulfhydryl or amino groups such as cysteine, glutathione. At this point, 6-mercaptopurine is metabolized by three enzymes. It is oxidized by xanthine oxidase to 6-thiouric acid, methylated by thiopurine methyltransferase to form 6-methyl-mercaptopurine and converted to 6-thioguanine nucleotides by hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase. 6-thiouric acid and 6-methyl-mercaptopurine are both inactive metabolites but may play a small role in drug toxicity. On the other hand, 6-thioguanine nucleotides are active metabolites that inhibit the de novo synthesis of purines and are incorporated into DNA as a false base which triggers cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.[7] Methotrexate inhibits xanthine oxidase and thus blocks metabolism of 6-mercaptopurine to inactive metabolite [Figure - 1]. This increases the amount of 6-methyl-mercaptopurine and 6-thioguanine nucleotides which might lead to an enhanced immunosuppression [Figure - 1]. According to Balis et al.[8] and Innocenti et al.,[9] methotrexate has been observed to enhance the bioavailability of azathioprine. However, such effects have been observed at high doses of methotrexate.

Bareham et al. experimentally proved the synergistic action of azathioprine-methotrexate combination.[10] He suggested that interaction of azathioprine and methotrexate is synergistic if azathioprine is given before methotrexate but additive if azathioprine is given after methotrexate.

Although no severe adverse effects of the combination therapy have been reported other than gastrointestinal and elevation of liver enzymes, a single study by Blanco et al. observed acute febrile toxic reaction in 4 out of 43 patients included in their study.[11] They developed acute fever with myalgia, arthralgia and an erythematous rash on the body including palms and soles. It resolved on withdrawing the drugs, but a rechallenge with azathioprine and methotrexate was limited by a new flare of reactions.

In our observation, after 40 weeks of treatment with combination of azathioprine and methotrexate, no adverse effects were observed. The patients not responding to any single immunosuppressive, responded to combination therapy, as well as the oral corticosteroids, which were effectively tapered.

Thus, combination therapy with azathioprine and methotrexate is a safe and effective long-term therapy for difficult to treat patients. The combination therapy has no additional severe toxicities. However, since it is an observation in only four patients, a long-term study with large sample size is required to establish these results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. | Willkens RF, Urowitz MB, Stablein DM, McKendry RJ Jr, Berger RG, Box JH, et al. Comparison of azathioprine, methotrexate, and the combination of both in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1992;35:849-56. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Willkens RF, Sharp JT, Stablein D, Marks C, Wortmann R. Comparison of azathioprine, methotrexate, and the combination of the two in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1995 Dec 1;38(12):1799-806. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Brio JA, Segal AM, Mackenzie AH, Mazanec DJ, Wilke WS. The combination of methotrexate and azathioprine for resistant rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1987; 30(suppl): S18. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Kakar A, Kumar A. Current status of combination therapy with disease modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. J Indian Rheumatol Assoc 2002;10:36-44. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Morris R.E. New small molecule immunosuppressants for transplantation: Review of essential concepts. J Heart Lung Transplant 1993;12(6 Pt 2):S275-86. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Berenbaum MC. Synergy, additivism and antagonism in immunosuppression: A critical review. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 1977;28(1):1-18. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Wise M, Callen JP. Azathioprine: A guide for the management of dermatology patients. Dermatologic therapy 2007 Jul 1;20(4):206-15. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Balis FM, Holcenberg JS, Zimm S, Tubergen D, Collins JM, Murphy RF, et al. The effect of methotrexate on the bioavailability of oral 6-mercaptopurine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1987;41:384-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Innocenti F, Danesi R, Di Paolo A, Loru B, Favre C, Nardi M, et al. Clinical and experimental pharmacokinetic interaction between 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1996;37:409-14. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Bareham CR, Griswold DE, Calabresi P. Synergism of Methotrexate with Imuran and with 5-Fluorouracil and Their Effects on Hemolysin Plaque-forming Cell Production in the Mouse. Cancer Res 1974;34:571-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Blanco R, Martinez- Taboada VM, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Acute febrile toxic reaction in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis who are receiving combination therapy with methotrexate and azathioprine. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:1016-1020. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

10,691

PDF downloads

2,170