Translate this page into:

A comprehensive approach to child sexual abuse: Insights for dermatologists

Corresponding author: Dr. Ranjit Immanuel James, Department of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India. ranjit_immanuel@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Muralidharan K, Manoj D, Sathishkumar D, James RI, Narayanareddy J. A comprehensive approach to child sexual abuse: Insights for dermatologists. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_246_2025

Abstract

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a serious public health issue in India, with long-lasting physical, emotional and psychological consequences. Dermatologists play a crucial, though often underappreciated, role in the identification and management of CSA due to expertise in recognising and interpreting cutaneous signs, which are the most common and visible indicators of abuse. The authors explore the pivotal role of dermatologists in the multidisciplinary approach to CSA, emphasising their involvement in history-taking, physical examination, injury interpretation, and forensic evidence collection. The article also discusses the importance of timely reporting to authorities and adhering to treatment protocols based on the prevalent guidelines. This article attempts to create awareness among practising dermatologists in India about their role in the early detection and comprehensive care of CSA survivors. We also believe that this article will act as a guiding force for them to manage CSA cases effectively.

Keywords

Child sexual abuse

cutaneous signs

forensic evidence collection

multidisciplinary approach

POCSO act

sexual abuse indicators

Introduction

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a serious global issue that devigastates childhood and often causes lasting harm. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines CSA as “the involvement of a child in sexual activity that they do not fully understand, cannot consent to, or for which they are not developmentally prepared, or that violates societal laws or taboos.”1,2

Estimates suggest a high prevalence of CSA in India, although it remains underreported.3,4 The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported 64,469 cases of CSA and 38,444 cases of child rape in 2022, averaging seven reported cases every hour, four of which involved rape.5 To address this, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act was enacted in 2012 as a gender-neutral law to safeguard children from sexual abuse.6 However, misdiagnosis, social stigma, and lack of awareness among caregivers and healthcare professionals continue to hinder reporting.1 Timely medical intervention is crucial to ensure both the well-being of affected children and access to justice.

Managing CSA survivors requires a multidisciplinary approach, including thorough history-taking, careful physical examination, injury interpretation, meticulous documentation, psychological support, and optimal forensic evidence collection. Accurate diagnosis necessitates an understanding of appropriate interview techniques, cultural practices, developmental milestones and normal genital and perianal anatomy in children. Survivors may present with acute medical or surgical issues without disclosing abuse or seek help weeks later when physical signs have diminished. In some cases, subtle or indirect symptoms may be the only indication of CSA. Therefore, selecting appropriate laboratory tests, including those for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and conditions that mimic abuse, is essential for a comprehensive assessment and effective management.7,8

Since cutaneous signs are among the most common and recognisable indicators of sexual abuse, dermatologists play a crucial role in identifying and managing affected children. This responsibility requires a high degree of clinical suspicion to differentiate signs of abuse from other causes, including accidental injuries, pathological conditions, cultural practices, physical abuse or self-inflicted harm. The coexistence of anogenital disease with sexual abuse can further complicate diagnosis and treatment.9 All clinicians, especially dermatologists, must be well-versed in evaluating children with suspected sexual abuse and understanding their legal obligations. This article aims to bridge that knowledge gap and provide essential insights for practicing dermatologists. The terms “child,” “patient,” and “survivor” will be used interchangeably throughout.

Sequence of events while managing a case of CSA

A survivor of CSA may seek medical attention through three primary pathways: (i) via a police requisition following a complaint lodged by the survivor or their guardian, (ii) by directly approaching a doctor or hospital for therapeutic care and/or forensic evidence collection, or (iii) through a court order after filing a complaint.9 Regardless of the route taken, it is essential to provide comprehensive healthcare while meticulously collecting and documenting evidence, ensuring the integrity of the chain of custody.10

However, the priority of all treating doctors should be to provide both medical care and psychological first aid to survivors. Therapeutic care may involve immediate treatment for physical injuries, addressing mental trauma, and offering services such as emergency contraception, pregnancy counselling, and STI care. It is also essential to provide psycho-social support, including counselling, rehabilitation, and follow-up care, to ensure that the survivor receives holistic care.

Medico-legal case (MLC) registration and intimation to the police

According to Section 19 of the POCSO Act, it is mandatory to report any case of sexual assault to the police. The survivor’s consent is not required for this. It aims to protect the child and their best interests while safeguarding other children from the same perpetrator. Additionally, it serves as a deterrent to potential abusers and ensures that perpetrators are held accountable for their crimes. Under Section 21 of the POCSO Act, doctors who fail to report cases of CSA may face penalties, including imprisonment for up to six months, a fine, or both. If the individual holds a position of authority within an institution, the punishment may extend to one year. Additionally, under Section 200 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (which replaces Section 166B of the Indian Penal Code), failure to report CSA cases can result in imprisonment for up to one year, a fine, or both.11

A recent analysis by the Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation found that two-fifths of POCSO Act cases (2017–2019) were closed without chargesheets, often as “cases true but insufficient evidence or untraced or no clue.”12 This underscores investigative gaps and the risks of reporting without the child’s understanding or willingness to engage. While consent is not legally required, obtaining it builds trust, encourages participation, and strengthens the case. The Support, Advocacy & Mental health interventions for children in Vulnerable circumstances And Distress (SAMVAD) 7-step process emphasises prioritising the child’s mental health before reporting.13 However, if the child remains at risk and safety cannot be ensured otherwise, reporting is mandatory, even without consent.

History

In CSA cases, history-taking is often more critical than physical examination, as clinical findings may resemble other dermatological conditions. However, obtaining a history can be challenging, as children may withhold disclosure due to guilt, shame, or fear. Younger children, in particular, may not fully comprehend the abuse and may not report it unless specifically asked.14 When verbal disclosures are absent, behavioural indicators play a key role in identification [Supplementary File 1].15

History should be taken in a private setting with a compassionate approach, focusing on details essential for medical care, including past medical and gynaecologic history, symptoms post-assault, and relevant assault details. As recounting the experience can be re-traumatising, it is crucial to balance the need for information with sensitivity to the child’s emotional state.7,16

The interviewer should use simple language, a neutral tone, and ideally, the child’s native language to create a comfortable environment.7,16 Since the dermatologist is also a stranger to the child, building trust is essential. Patience, empathy, and a non-judgmental approach can help reassure the child. The interviewer should ensure confidentiality.16 In some cases, multiple visits may be necessary before ruling out abuse. A detailed history of penetrative assault should be recorded, along with any prior medical treatment. Previous anogenital surgeries and vaccination status, including tetanus and hepatitis B, should be documented to assess prophylaxis needs.17 For female children, menstrual history should be noted, and if indicated, maternal STI history should be reviewed to rule out vertical or perinatal transmission.18

Examination of the survivor

The examination should take place in a private setting, ensuring the survivor’s privacy, with a chaperone present always. According to Section 27(2) of the POCSO Act, a female child must be examined by a female doctor. If unavailable, a male doctor may conduct the examination in the presence of a female attendant.10 Before beginning, the survivor should be reassured that they have full control over the process and can pause or stop at any time. The primary objectives of the examination are to assess medical needs and collect forensic evidence.

Prerequisites for the examination of the survivor

A requisition from the police or magistrate is not mandatory for examining a survivor.19 So, a doctor cannot insist on a requisition from either of them to proceed with managing a case of CSA. However, if a complaint to the police is made and they bring a survivor to the hospital for medical examination and treatment, they will usually provide a requisition for the same.

Consent

Written informed consent must be obtained separately for medical treatment and medicolegal examination, including evidence collection.

-

If the child is under 12 years of age, consent must be given by a parent or guardian.

-

If the child is 12 years or older, they can consent to a general physical examination and non-invasive medicolegal procedures. If a parent or guardian refuses consent in such cases, the child’s consent takes precedence.

-

A child under 18 years cannot provide consent for invasive procedures, such as evaluation under anaesthesia; only a parent or guardian can give consent.

In rare situations where a parent or guardian is unavailable to consent for a child under 12 years, a panel of doctors and hospital administrators may provide consent on the child’s behalf.9 Similarly, for children with special needs, such as those with visual impairments or mental challenges, if a parent or guardian is unavailable, consent is obtained from the guardian appointed by the Child Welfare Committee (CWC).9 If a parent or guardian acts against the child’s best interests, particularly in cases of incest, the CWC must be informed, as it holds the legal responsibility to ensure the child’s care and protection.9,20

Physical examination

A complete physical examination is crucial, as it can provide valuable clues about abuse. A thorough head-to-toe examination, in addition to the anogenital examination, should be conducted as soon as possible after the incident. Anthropometric measurements should also be recorded to assess for possible child neglect.21 Mucocutaneous lesions in the head and neck region, including the oral cavity, account for up to 60% of injuries in CSA survivors. The mnemonic “TEN FACE sp,” proposed by Pierce et al., helps identify abuse-related injuries (Torso, Ears, Neck, Frenulum, Angle of jaw, Cheeks, Eyelids, Subconjunctival haemorrhage, and Patterned bruises).22 This mnemonic has a 97% sensitivity and 87% specificity in predicting child abuse.16 In cases of forceful sexual abuse, children may sustain both acute and healed injuries that should be carefully documented. It is important to look for abrasions, bruises, burns, scars, and signs of STIs, as both old and new injuries can provide critical forensic and clinical insights.21

The examining physician must thoroughly understand normal genital anatomy and its variations to distinguish between normal findings, trauma-induced changes, and signs of abuse.23 Not all CSA cases present with obvious findings - most confirmed cases involving penetration show a normal anogenital exam, either due to the absence of injury or healing before the examination.24 Studies indicate that abnormal genital lesions are found in only 4% of children evaluated for sexual abuse, highlighting that a normal exam does not rule out abuse.25

Examination of the oral cavity: Tears of the labial or lingual frenulum, lacerations, oedema of the oral mucosa and lips, and unexplained erythema or petechiae at the hard-soft palate junction may indicate forced oral sexual abuse. However, other traumatic causes must be ruled out before attributing these findings to abuse.26,27 The presence of condyloma acuminata or oral ulcers can also suggest CSA and STI in children.28

Examination of genitalia

Assess the external genitalia, perianal region, and regional lymph nodes, especially if STI is suspected. Look for erythema, oedema, bleeding, tears, abrasions, lacerations, warty growths, and bite marks on the labia, vulva, glans penis, penile shaft, and, less commonly, the scrotum. Circumferential injuries on the penile shaft may indicate abuse. STI features, such as ulcers, vesicles, erosions, and purulent discharge, should be noted. Examine the urethral meatus for erythema, abrasions, bleeding, or discharge.7 If the survivor is menstruating, a follow-up examination is necessary to document injuries accurately. As menstrual shedding may result in evidence loss, it is crucial to record the survivor’s menstrual status at the time of assault and examination.10,17

Examination positions:

-

Prepubertal children: Use the supine “frog-leg” position or knee-chest position for genital examination.

-

Adolescents: Lithotomy position, followed by the knee-chest position, is advised.

For detailed visualisation, employ labial traction and separation.29,30 The perianal region should be examined in the supine or prone knee-chest position and the lateral decubitus position, with the glutei separated.30

Evaluating the hymen is crucial as normal variations exist depending on age and hormonal influences. In infancy and puberty, the hymen is typically thick, light, and elastic, whereas in prepubertal children, it tends to be thin and vascular. Hymenal injuries can indicate sexual abuse, making this assessment vital.7,17

Per speculum examination is not required if there is no history of penetration and no visible injuries. However, in cases of severe injuries, the examination and necessary treatment may need to be performed under general anaesthesia.10,31 Normal genitalia and perianal variants have been described in Supplementary File 2.7,18

Examination findings can be categorised into two main groups: those that are highly specific and strongly suggest sexual abuse, and those that are highly suspicious of abuse. The latter includes changes that might be indicative of sexual abuse but could also result from other dermatological conditions or trauma [Table 1].7,26,30 STIs in children beyond the neonatal period are highly specific for sexual abuse.32

| Highly specific for abuse | Suspicious of abuse |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In a study on anal and perianal changes in sexually abused prepubertal children, abnormalities were found in only 34% of cases, with anal gaping, skin tags, rectal tears, and sphincter tears being the most common. Bite marks were observed in one female child.29 While anogenital warts are typically considered an STI, HPV can also spread through non-sexual routes, including close physical contact, autoinoculation, fomites, and perinatal transmission.33 Although perinatal transmission is plausible up to 24 months, the likelihood of sexual abuse increases with age. Reports suggest similar prevalence rates of anogenital warts in abused and non-abused children.33,34

Various dermatological conditions and accidental injuries can mimic signs of CSA [Supplementary File 3].7,26,35 The diagnostic implications of STIs potentially linked to CSA have been outlined in Table 2.32,36

| Infection | Evidence of abuse | Reporting to the Police |

|---|---|---|

| Gonorrhoea | Diagnostic # | Report |

| Syphilis | Diagnostic * | Report |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Diagnostic# | Report |

| Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) | Diagnostic # | Report |

| Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) | Diagnostic * | Report |

| Genital herpes | Suspicious | Report |

| Human Papilloma virus (HPV) | Suspicious † | Report |

| Bacterial vaginosis | Inconclusive | Follow up |

| Anogenital molluscum contagiosum | Inconclusive | Follow up |

| Hepatitis B virus | CSA can be considered * | - |

| Hepatitis C virus | CSA can be considered * | - |

| Others (Mycoplasma genitalium, Campylobacter, Shigella, Neisseria meningitidis) | Suspicious |

Report if additional evidence of CSA present |

# If perinatal transmission is excluded, then report to the Police, * If not acquired perinatally or via blood transfusion, then report to the Police, † If non-sexual mode of transmission is excluded, then report to the Police

Investigations

The decision on investigations and treatment should be individualised after discussion with the parent or guardian. STI screening is recommended in the following cases:32

-

Penetrative genital or anal assault

-

Abuse by a stranger with unknown medical history or STI status

-

Perpetrator known to have or be at high risk for STIs (e.g., IV drug users, Men Who have Sex with Men (MSM), individuals with multiple partners)

-

The child has a sibling or relative with STI

-

Presence of STI symptoms or a prior STI diagnosis

-

I.

-

II.

Serology for syphilis, HIV, Hepatitis B and C, Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)

-

III.

Urine pregnancy test

-

IV.

Biopsy for confirmation of STI-related lesions

| Investigations | Sample |

|---|---|

| Gram stain for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Bacterial vaginosis, Candida |

Pharyngeal, vaginal, cervical, urethral, anorectal, discharge (prepubertal children - cervical swab not taken) |

|

Wet mount for Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), bacterial vaginosis Culture for TV using Diamond’s media or InPouch TV media |

Vaginal discharge |

|

Culture Nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

Pharyngeal, vaginal, cervical, urethral, anorectal, urine (prepubertal children - cervical swab not taken) |

|

Tzanck smear Culture NAAT for Herpes simplex virus (HSV) HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) HSV serology |

Vesicles, erosions, ulcers |

Collection and preservation of evidence

Collecting and preserving evidence in sexual assault cases is vital for establishing the assault, identifying suspects, and corroborating the survivor’s statements.10,35,36 Evidence collection should be guided by the history, including penetration type (penetrative/non-penetrative, penile/non-penile), affected orifice (vagina, anus, mouth, urethra), and ejaculation. Post-assault activities like bathing, douching, urination, or defecation should also be considered. Detailed evidence collection steps have been provided in Supplementary File 4.10,31,37

Treatment

-

1.

Informed consent must always be obtained before initiating any treatment or referring the survivor to other services.17

-

2.

Treatment of physical injuries: Address and treat any physical injuries sustained by the survivor as needed.

-

3.

-

4.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP): PEP for HIV and STIs should be considered based on individual risk assessment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) generally advises against presumptive STI treatment for prepubertal children following sexual assault due to the low incidence of STIs in this age group and the feasibility of follow-up. Additionally, the risk of ascending infection is lower in prepubertal girls compared to adolescents and adults. However, if parents express concern about STI transmission, presumptive treatment may be considered, provided that necessary samples have been collected beforehand.32

| STI | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Syphilis (acquired) |

Primary, secondary syphilis - Benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight IM, up to the adult dose of 2.4 million units in a single dose. |

|

Gonorrhoea Uncomplicated gonococcal vulvovaginitis, cervicitis, urethritis Proctitis, pharyngitis) |

Infants and children ≤45 kg: ceftriaxone 25-50 mg/kg body weight by IV or IM in a single dose, not to exceed 250 mg IM For children >45 kg and adolescents: ceftriaxone 500 mg by IM single dose |

| Chlamydial infection |

Infants and children <45 kg (nasopharynx, urogenital, and rectal): Erythromycin base, 50 mg/kg body weight/day orally, divided into 4 doses daily for 14 days OR Ethyl succinate, 50 mg/kg body weight/day orally, divided into 4 doses daily for 14 days Children who weigh ≥45 kg, but who are aged <8 years (nasopharynx, urogenital, and rectal): Azithromycin 1 gm stat dose orally Children aged ≥ 8 years: Azithromycin 1 g orally single dose OR Doxycycline 100 mg orally 2 times daily for 7 days # |

| Trichomonas vaginalis |

Metronidazole 15 mg/kg/day in 3 doses given orally for 7 days For children >12 years: Females – 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days; Males - metronidazole 2 g orally single dose |

| Herpes simplex virus |

1st episode: <12 years: Acyclovir orally 40 to 80 mg/kg/day in 3 to 4 divided doses for 7 to 10 days ≥12 years and adolescents: Acyclovir orally 400 mg 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days |

#Azithromycin may be considered as an alternative to doxycycline, as per National AIDS Control Organisation recommendations. IV: intravenous, IM: intramuscular.

For adolescent survivors, the CDC recommends empirical treatment:32

-

Females: IM ceftriaxone (500 mg), oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 7 days), and oral metronidazole (500 mg twice daily for 7 days).

-

Males: IM ceftriaxone (500 mg) and oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 7 days).

National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) guidelines for survivors >45 kg include:

-

Chancroid, gonorrhoea, chlamydia: IM ceftriaxone (500 mg) + oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 7 days) or oral azithromycin (1 g) + cefixime (800 mg) as a single dose.

-

Trichomoniasis and bacterial vaginosis: A single dose of secnidazole (2 g), metronidazole (2 g), or tinidazole (2 g).17

For children >45 kg, NACO recommends:17

-

Chancroid and chlamydia: Oral azithromycin (20 mg/kg, single dose).

-

Gonorrhoea: Oral cefixime (8 mg/kg, single dose) or IM ceftriaxone (125 mg).

-

Trichomoniasis: Oral metronidazole (15 mg/kg per dose, thrice daily for 7 days).

HIV PEP should be decided on a case-by-case basis, considering risk assessment and caregiver counselling on potential benefits and toxicities.32

-

5.

-

6.

Vaccination: The Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices (ACIP) recommends HPV vaccination for children and adolescents (both males and females) aged 9 years and above if they are unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated. Additionally, adolescents should receive Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (0.06 mL/kg) and the first dose of the Hepatitis B vaccine if unvaccinated and the abuser’s vaccination status is unknown.17,32 Tetanus toxoid (TT) should be administered to survivors with injuries who have not been immunised.17

-

7.

Follow-up: A follow-up examination after two weeks is recommended to complete any pending physical examinations or investigations. If baseline tests are normal but STI transmission is a concern, repeat serological tests for syphilis and Hepatitis B at 6 and 12 weeks, and HIV serology at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months to avoid false-negative results. Follow-up testing should be tailored to each case.32

-

8.

Psychosocial Support: Sexual abuse often occurs alongside other forms of physical or emotional abuse. The psychological trauma from abuse can lead to depression, anxiety, emotional instability, and even suicidal ideation, with long-term consequences. Therefore, timely supportive therapy and referral for psychological counselling are crucial.39,40

Documentation and opinion

The examination must be thoroughly documented using the prescribed format by the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India.10 This includes survivor details, accompanying persons, informed consent (or refusal), identification marks, history, examination findings, sample collection, and the doctor’s opinion.10,31,37

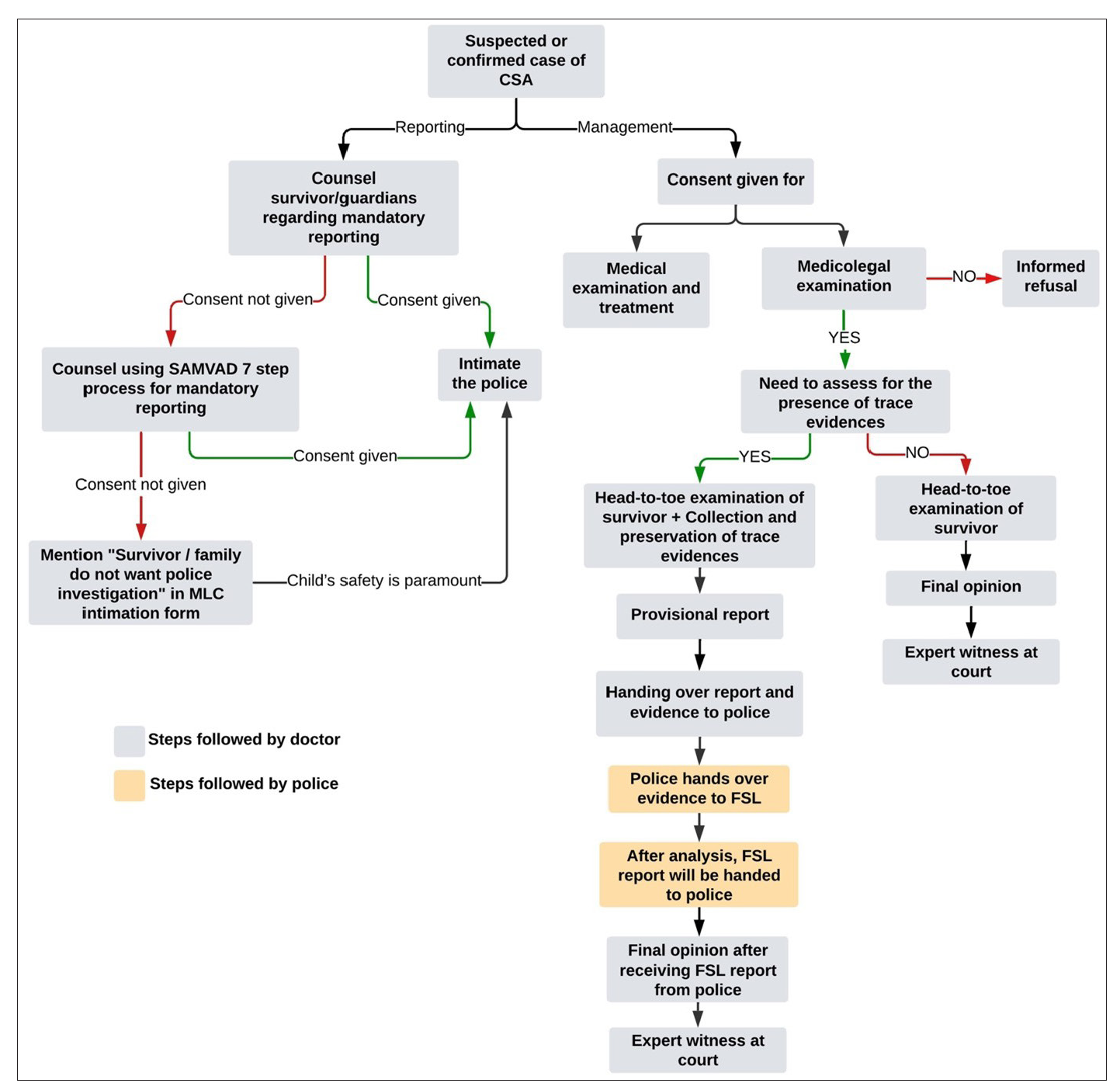

The doctor should provide an opinion only after reviewing all available information. If samples (e.g., swabs for sperm/semen, blood for grouping, DNA analysis) are sent to the forensic science laboratory (FSL), a provisional opinion should be issued.21A final opinion can be given after reviewing all test results and relevant documents. The workflow for CSA cases has been shown in Figure 1.

- The sequence of events in managing a case of CSA. (FSL: Forensic science lab, MLC: Medicolegal case.)

Recommendations

Dermatologists should undergo regular training on recognising dermatological signs of CSA and understanding their medicolegal obligations. Implementing standardised screening protocols for suspicious cutaneous injuries, adequate documentation, and ensuring appropriate referrals can improve early detection.41 Collaboration with paediatricians, forensic experts, microbiologists, psychiatrists, and social workers is essential for a multidisciplinary approach to holistic care. Additionally, educating caregivers about recognising abuse, importance of timely reporting, and available support services can aid in safeguarding children. Lastly, contributing to research on CSA-related dermatological findings can strengthen early detection and intervention measures.

Conclusion

It is crucial for dermatologists to be aware of the medicolegal implications of CSA cases. By integrating these recommendations into clinical practice, dermatologists can enhance early CSA detection, ensure appropriate management, and fulfil legal responsibilities, ultimately playing a key role in the holistic management and prevention of CSA.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Knowledge and attitude of physicians toward child abuse and reporting in a tertiary hospital in riyadh. J Family Med Prim Care.. 2022;11:6988-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Child maltreatment. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment. Accessed July 2, 2024

- Implications of the POCSO act and determinants of child sexual abuse in India: Insights at the state level. Humanit Soc Sci Commun.. 2023;10:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Under reporting of child sexual abuse- the barriers guarding the silence. TJP.. 2020;4:57-60.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crime in India - All Previous Publications. National Crime Records Bureau. 2022. Available from: https://www.ncrb.gov.in/uploads/nationalcrimerecordsbureau/custom/1701607577CrimeinIndia2022Book1.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2024.

- Ministry of Law and Justice. Govt of India. The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012; 2012. Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2079/1/AA2012-32.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2024.

- Cutaneous signs of child abuse. J Am Acad Dermatol.. 2007;57:371-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Public Health & National Health Mission, Government of Maharashtra. Strengthening health sector response to violence: A kit. (Medical Examination of Survivors/Victims of Sexual Violence: A Handbook for Medical Officers); 2017. Available from: https://india.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Violence Kit-1.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2024.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. Guidelines & protocols: Medico-legal care for survivors/victims of sexual violence; 2014. Available from: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/953522324.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2024.

- Ministry of Law and Justice. Govt of India. The protection of children from sexual offences (Amendment) Act, 2019; 2019. Available from: https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-12/20-11-2019%5B1%5D.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2024.

- Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation. Police case disposal pattern: An enquiry into the cases filed under POCSO Act; 2021. Available from: https://satyarthi.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Police-Case-Disposal-Pattern.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2024.

- National Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences. Guidelines for mandatory reporting in child sexual abuse cases; 2021. Available from: https://nimhanschildprotect.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Guidelines-for-Mandatory-Reporting-in-Child-Sexual-Abuse-cases.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2024.

- Reports of child abuse in India from scientific journals and newspapers - Anexploratory study. Online J Health Allied Sci.. 2013;12:4-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention; 1999. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/65900/ WHO_HSC_PVI_99.1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed July 15, 2024.

- Child abuse: A social evil in Indian perspective. J Family Med Prim Care.. 2021;10:110-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organization, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. National technical guidelines on sexually transmitted infections and reproductive tract infections; 2024. Available from: https://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/National%20Technical%20Guidelines%20on%20STI%20and%20RTI_Final.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2024.

- Physical examination in child sexual abuse. Dtsch Arztebl Int.. 2014;111:692-703.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- State of Karnataka v. Manjanna, 2000 INSC 283.

- Ministry of Law & Justice, Government of India. Juvenile justice (Care and protection of children) Act; 2015. Available from: http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2016/167392.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2024.

- A roadmap for saviours: Role of doctors in medicolegal care in relation to POCSO ACT. International Journal of Medical Justice.. 2023;1:47-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M, Kaczor K, Lorenz D, Makoroff K, Berger RP, Sheehan K. Bruising clinical decision rule (BCDR) discriminates physical child abuse from accidental trauma in young children. In Pediatric Academic Societies’ Annual Meeting 2017. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=In%20Pediatric%20Academic%20Societies%27%20Annual%20Meeting%202017&title=Bruising%20clinical%20decision%20rule%20(BCDR)%20discriminates%20physical%20child%20abuse%20from%20accidental%20trauma%20in%20young%20children&author=M%20Pierce&author=K%20Kaczor&author=D%20Lorenz&author=K%20Makoroff&author=RP%20Berger&

- Examination for sexual abuse in prepubertal children: Anupdate. Pediatr Ann.. 1997;26:312-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interpretation of medical findings in suspected child sexual abuse: An update for 2018. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol.. 2018;31:225-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children referred for possible sexual abuse: Medical findings in 2384 children. Child Abuse Negl.. 2002;26:645-59.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skin manifestations of child abuse. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol.. 2010;76:317-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous manifestations of physical and sexual child abuse. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol.. 2020;21:1.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Condyloma acuminata in the tongue and palate of a sexually abused child: A case report. BMC Res Notes.. 2014;7

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anal and perianal abnormalities in prepubertal victims of sexual abuse. Am J Obstet Gynecol.. 1989;161:278-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updated guidelines for the medical assessment and care of children who may have been sexually abused. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol.. 2016;29:81-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challenges in the management of child sexual abuse in India. Journal of Punjab Academy of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology.. 2022;22:161-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep.. 2021;70:1-187.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection in children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr.. 2009;168:267-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A practical approach to warts in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care.. 2008;24:246-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The cutaneous manifestations and common mimickers of physical child abuse. J Pediatr Health Care.. 2004;18:123-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexually transmitted diseases in prepubertal children: Mechanisms of transmission, evaluation of sexually abused children, and exclusion of chronic perinatal viral infections. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis.. 2005;16:317-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexual Offences. In: Textbook of forensic medicine and toxicology. New Delhi: Arya Publishing Company; 2016. p. :445-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of herpes simplex virus infections in pediatric patients: Current status and future needs. Clin Pharmacol Ther.. 2010;88:720-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Child sexual abuse: Management and prevention, and protection of children from sexual offences (POCSO) act. Indian Pediatr.. 2017;54:949-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev.. 2009;29:328-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contours of Justice: Unveiling Forensic Dermatology in India. Indian Dermatol Online J.. 2025;16:202-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]