Translate this page into:

A longitudinal study of consistency in diagnostic accuracy of teledermatology tools

Correspondence Address:

Garehatty Rudrappa Kanthraj

Sri Mallikarjuna Nilaya, # HIG 33, Group 1 Phase 2, Hootagally KHB Extension, Mysore - 570 018, Karnataka

India

| How to cite this article: Kanthraj GR. A longitudinal study of consistency in diagnostic accuracy of teledermatology tools. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013;79:668-678 |

Abstract

Background: Diagnostic accuracy (DA) is an outcome measure to assess the feasibility of teledermatology tools. Despite ample data with variable DA values, no study has examined the aggregate DA value obtained from the available studies and observed its consistency over a period of time. This kind of a longitudinal study about teledermatology will be necessary to check its usefulness and plan for further implementation. Aims: To observe the DA trend over a period of 15 years (1997-2011). Methods: Only those studies (n = 59) using a single tool for general, tertiary, and subspecialty teledermatology practice were included to obtain the DA values. Studies were graded based on the number of subjects and gold standard comparison between teledermatologist and clinical dermatologist (face-to-face examination). Results: This analysis sought to identify the DA trend was carried out by evaluating 17 store and forward teledermatology (SAFT) based and 8 Video conference (VC) tool-based studies with 2385 and 1305 patients respectively, in comparison with the gold-standard assessment. The average DA was 73.35% ± 14.87% for SAFT and 70.37% ± 7.01% for VC. One sample t-test analysis with 100% accuracy as standard value revealed 28% deficiency for SAFT (t = 7.925; P = 0.000) and 30% deficiency for VC (t = 11.955; P = 0.000). Kruskall-Wallis test confirmed the consistency of DA values in the SAFT (χ2 = 1.852, P = 0.763) tool. Conclusion: SAFT and VC were adequately validated on a large number of patients by various feasibility studies with the gold standard (face-to-face) comparison between teledermatologists and clinical dermatologists. The DA of SAFT was good, stable over the 15 years and comparable to VC. Health-care providers need to plan for appropriate utility of SAFT either alone or in combination with VC to implement and deliver teledermatology care in India.Introduction

The term "teledermatology" was coined by Prednia and Brown in 1994. [1] In 2001, Edey and Wooten [2] reviewed the pros and cons of both store and forward teledermatology (SAFT) and video conference (VC) tools. Huntley and Smith [3] in 2002 underscored the importance of internet and its role to pool experts′ opinion for difficult to manage cases. Braun et al.[4] demonstrated telemedical wound care using the mobile phones. Besides, various traditional reviews [5],[6],[7] have contributed to the insights into teledermatology. In 2008, Kanthraj [5] proposed the classification of teledermatology practice (TP). A revised classification was presented in 2011 [6] to incorporate tertiary teledermatology. Teledermatologists like Emnovic et al, [8] Warhaw et al.[9] and Van der Heijden et al.[10] have systematically reviewed and summarized the application of VC, SAFT and tertiary teledermatology.

A successful implementation of TP in a given health-care setting depends on technical feasibility of a teledermatology tool (TT) and factors like patient and physician willingness and satisfaction for the technology. [11] The competence of TTs is demonstrated in a clinical setting by feasibility studies. The diagnostic accuracy (DA) is an outcome measure obtained from a feasibility study that evaluates a teledermatology tool when a teledermatologist diagnosis is compared with a face-to-face examination by a clinical dermatologist (gold standard) followed by the statistical analysis (kappa value) of the data.

A plethora of feasibility studies [12],[13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45],[46],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52],[53],[54],[55],[56],[57],[58],[59],[60],[61],[62],[63],[64],[65],[66],[67],[68],[69],[70],[71] have been conducted to test the competence of TTs with or without a gold standard comparison between clinical and teledermatologists. Few authors [12],[13],[14],[15],[16],[17] have compared teledermatologists with nurses, general practitioners and documented DA while others [18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24] have compared between teledermatologists with a clinical dermatologist and obtained the results. These varying outcomes have all contributed to the quandary of reliable DA value for TTs. Most notably, despite extensive and accelerated dissemination of teledermatology reports, there is no study that has examined the aggregate DA of a TT and observed its consistency over a period of time. In this milieu, a longitudinal study was undertaken for the first time to observe the DA trend of various TTs. Feasibility, the practicability of a TT in terms of both technical (technology) and clinical (diagnosis) was analyzed in this study; this is an important area of investigation because the findings could help to determine the usefulness of TP and its further implementation for community health-care program.

Methods

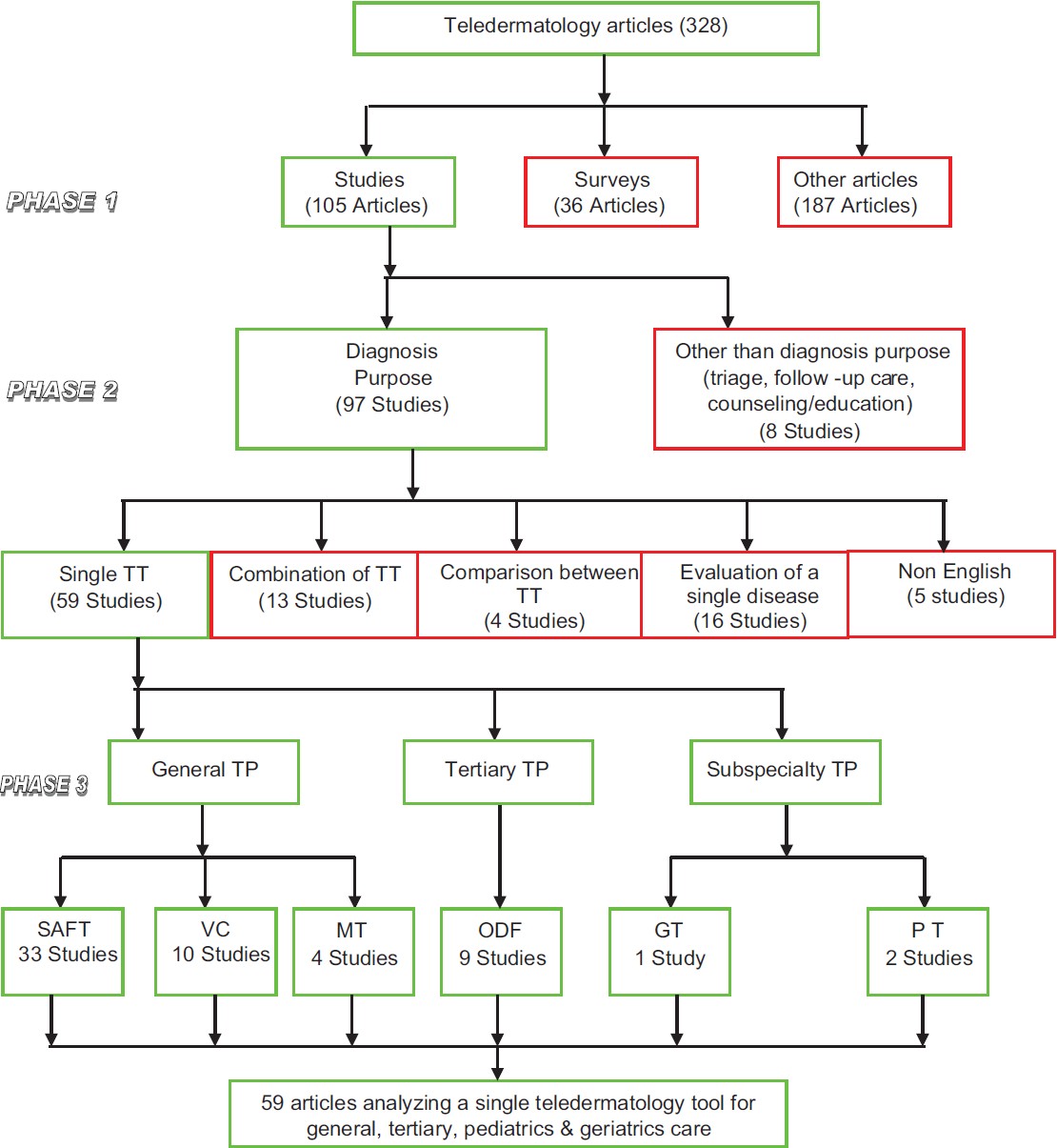

The steps entailed in the study were identification of studies with a single TT for general, tertiary, pediatrics and geriatrics teledermatology care, addressing dermatological conditions of general out-patient setting that are diagnosed mostly by spot examination. The purpose of this study was to compare the TT with reference to a gold standard (face-to-face examination) and we did not focus on the type of case mix involved in each study. All the 328 articles in PubMed obtained after using the search term "teledermatology" and "TP" were categorized as (a) 105 studies (b) 36 surveys (c) and 187 other than study or survey articles. The inclusion and exclusion of articles are shown in [Figure - 1]. Furthermore, in these 97 studies, 59 studies assessing the DA of single TT used for diagnostic purpose were included. The 38 studies were excluded based on the following decisive factors: (a) combination of TTs used for diagnostic purpose (13 studies) as the combination of tools would interfere in the proper assessment of a single tool. (b) Studies focusing on a single clinical entity (16 studies) (c) comparison between two TTs (4 studies) and (d) non-English articles (5 studies). Studies that employed additional or special TT like teledermoscopy were excluded.

|

| Figure 1: Included and excluded feasibility studies on teledermatology tools (TT: Teledermatology tool, TP: Teledermatology practice, SAFT: Store and forward teledermatology, VC: Video conference, MT: Mobile teledermatology, ODF: Online discussion forum, PT: Pediatric teledermatology, GT: Geriatric teledermatology) |

Gold standard diagnosis is the face-to-face consultation with histopathology confirmation. However, we considered all the teledermatology studies compared with face-to-face examination alone to be the minimum standard and were included. The DA values obtained from all the complete feasibility studies that compared the DA between the clinical dermatologist (face-to-face examination as the gold standard) and teledermatologist that evaluated a single TT were included and unified for overall analysis. The DA values obtained from studies without gold standard comparison, absence of DA comparison between teledermatologist with a clinical dermatologist, retrospective analysis were excluded. Fifty nine included studies [13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45],[46],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52],[53],[54],[55],[56],[57],[58],[59],[60],[61],[62],[63],[64],[65],[66],[67],[68],[69],[70],[71] [Table - 1] were read completely and analyzed individually based on (a) TT assessed on the number of subjects, i.e., more than 100 patients was considered as a major study while less than 100 as a small study (b) presence or absence of the gold standard comparison (face-to-face examination) between the diagnosis, i.e., primary (diagnosis) or secondary (differential diagnosis) offered by teledermatologist were compared with clinical dermatologist. Based on these criteria, the studies were graded as grade 1, the DA obtained from a prospective study after testing over a large number of patients (>100) with the gold standard comparison. A prospective small study with the gold standard comparison between a teledermatologist with a clinical dermatologist is grade 2. A prospective large study (>100 subjects) without a gold standard comparison is grade 3. A small study without a gold standard comparison is 4. A grade 5 study is a retrospective analysis of the data or a study that establishes the feasibility without documenting DA.

Total number of feasibility studies included to evaluate a single TT used for diagnostic purpose in general, tertiary or subspecialty care TP was 59. [13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45],[46],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52],[53],[54],[55],[56],[57],[58],[59],[60],[61],[62],[63],[64],[65],[66],[67],[68],[69],[70],[71] They were grouped according to the working classification of TP [5] [Table - 2]. Although Mobile teledermatology (MT) is a variant of SAFT and VC, MT differs in net connectivity technology and dermatology care is provided by using cell phones. Subspecialist care in pediatric and geriatric teledermatology has emerged focusing the dermatological conditions of those age groups. This is reflected in the teledermatology literature. Hence, the studies were placed as separate entities.

Most of the studies 51% (33) were on SAFT [13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45] for general teledermatology (Seventeen studies [19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35] on SAFT with the gold standard comparison (Grade 1-2) were included, 10 studies [36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45] without a gold standard comparison (Grade 3-5) were excluded. Furthermore, there were 6 studies on SAFT [13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18] that were excluded as these studies had a gold standard comparison with face-to-face examination; however, the comparison was carried out by a nurse or general practitioners and not a dermatologist. This can result in variation of DA values.

In VC tool, there were 19% (10) of feasibility studies, [46],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52],[53],[54],[55] eight studies [46],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52],[53] with the gold standard comparison were included (Grade1-2), and two (Grade3-5) studies [54],[55] without a gold standard comparison were excluded. MT had four (8%) small studies [56],[57],[58],[59] (Grade 2). There were 17% (9) of feasibility studies on tertiary [60],[61],[62],[63],[64],[65],[66],[67],[68] (second opinion) teledermatology, three studies [60],[61],[62] with the gold standard comparison were included and six studies [63],[64],[65],[66],[67],[68] without a gold standard comparison were excluded for analysis on online discussion forum (ODF). The sub-specialty TP included 4% (2) and 2% (1) studies with the gold standard comparison for pediatric [69],[70] and geriatric [71] TP respectively.

Author, year of publication, number of subjects, gold standard comparison between teledermatologist versus clinical dermatologist and DA were noted from each study with respect to each TTs and analysis of DA trend over a period of time (15 years), from 1997 to 2011 was performed. They are summarized in [Table - 1].

The DA trend of a TT over a 15 year period

Grade 1 and 2 studies were included for analysis. The studies were arranged accordingly in the chronological year in which they were published. Number of studies, enrolled patients and DA were noted for a consecutive 3 year period up to 15 years (1997-2011) and the DA trend was analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, Chi-square, one-sample t-tests were employed using a statistical package (SPSS for windows version 17, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) to analyze the data. Non- parametric tests of Mann-Whitney U and Kruskall Wallis tests were performed.

Results

The analysis of various studies on TTs, number of studies, patients, and their average DA values are shown in [Table - 2].

Comparison of DA of SAFT, VC versus 100% accuracy as standard value

The average DA obtained from 17 studies [19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35] with gold standard comparison on SAFT were 73. 35 ± 14.87 and the average value for VC with 8 studies [46],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52],[53] with the gold standard comparison were 70.37 ± 7.01 [Table - 3]. Assessment with t-test (independent samples) for inter comparison between SAFT and VC with respect to the number of patients were insignificant. The DA was comparable between both the methods. There is no significant difference between DA values of SAFT and VC [Table - 3]. One sample t-test analysis with 100% accuracy as standard value revealed 28% of deficiency for SAFT (t = 7.925), P = 0.000 and 30% deficiency for VC (t = 11.955, P = 0.000).

Three-year consecutive DA of SAFT and VC assessed over a 15 year (1997-2011) period

Analysis of 3 year DA trend of SAFT included 17 studies [19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35] with the gold standard comparison (grade 1 and 2) altogether tested on 2385 patients confirmed a consistent trend with 73.35% ± 14.87% [Table - 3]. The Kruskall Wallis test (χ2 = 1.852, P = 0.763) confirmed the consistent DA values of SAFT over a 15 years period (1997-2011) [Figure - 2]. VC was evaluated by 8 studies [46],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51],[52],[53] with the gold standard comparison and 1305 patients were enrolled from 1997 to 2001. Mann-Whitney U test analyzed average DA 70.37% ± 7.01% for VC. A consecutive 3 year DA trend indicated the values were consistent. (u = 3.00, P = 0.429) [Table - 3]. There were no further studies with the gold standard comparison on VC after 2001.

|

| Figure 2: Comparison of regular 3-year diagnostic accuracy trend of store teledermatology and forward and Videoconference over a period of 15 years (1997-2011) |

Discussion

The concept of DA itself has certain pitfalls especially in the manner in which it was reported - variation in the level of training of both the referring physician and the teledermatologist, inter observer variability, and percentage agreement/kappa statistics.

There were no uniform standards followed in the methodology to conduct feasibility studies. Discrepancy to capture images, camera resolution, inter-observer variation, difference in training and expertise on the subject may explain the DA variation. The clarity of images, speed of the internet and rapidity of teleconsultation has improved compared to those used in studies of 10 years back. The wide variation in DA margin may be minimized by the following measures: (a) comparison with a gold standard face-to-face examination (b) diagnosis made by teledermatologist should be compared with a clinical dermatologist c) adherence to the standards proposed by American teledermatology association and practice guidelines [72] that ensure a minimum standard for TP, uniformity in the methodology with reproducible results.

Only small studies were available for MT and therefore, extensive studies are required in this field. Most of the studies on ODF [60],[61],[62],[63],[64],[65],[66],[67],[68] were retrospective analysis. However, ODF is a modification of SAFT and the principles of SAFT matches exactly with ODF. There were studies with the gold standard comparison on SAFT adjudicating that SAFT is a time-tested technology for the past 15 years with better DA as analyzed in the present study and separate studies on technical feasibility of ODF may not be required.

There are sparse studies with the gold standard comparison that encourage sub-specialty care like pediatric [69],[70] and geriatric [71] teledermatology. Research in these areas would facilitate the implementation of teledermatology program in a health-care setting. The 15 years (1997-2011) data analysis confirmed SAFT and VC were the tools evaluated by studies with the gold standard comparison on a significant number of patients with good DA. SAFT is a regularly validated tool from past one and half decades with a consistent DA when compared to VC. The DA is almost similar in both SAFT and VC; however, SAFT has a consistent DA and it is an easy, convenient and cost-effective [73],[74],[75] tool that makes it the most widely used technology.

The stable DA despite the technical advances in this field suggests dermatological conditions that can be diagnosed by face-to-face examination be able to diagnosed by teledermatology. Though, VC has a consistent and good DA, general practitioners, dermatologists and patients are required for simultaneous interaction making this sort of practice a more time consuming tool. SAFT is being used as an effective alternative to VC and dermatologists are using SAFT frequently and consistently for research and practice.

The current longitudinal study observed that feasibility studies have shown both SAFT and VC tools were adequately validated with large feasibility studies involving ample number of patients with the gold standard comparison between teledermatologist and clinical dermatologists. The DA values for both SAFT (average 73.35%) and VC (average 70.37%) are good and comparable. Hence, these two tools are feasible for TP. SAFT is simple and easy to use. However, it has a limitation of absence of patient interaction with dermatologists, which is practiced by videoconference. A combination of SAFT and VC-hybrid teledermatology can improve DA, provide better patient satisfaction and disadvantages of SAFT or VC used alone can be overcome by this combination of SAFT and VC.

A significant difference was observed when SAFT and VC were compared with face-to-face (gold standard) and when DA is assumed as 100% accuracy (standard value). Dermatology is a visual specialty and most of the dermatological conditions can be diagnosed by face-to-face consultation (considered as the gold standard) or spot diagnosis alone. However, certain conditions like pigmented skin lesions may not be diagnosed appropriately by face-to-face and require additional investigations. Therefore, those dermatological conditions that are diagnosed by face-to-face can be diagnosed by teledermatology. However, dermatological conditions with ambiguity may require any of the following two approaches (a) initial TP followed by face-to-face examination and (b) initial face-to-face examination followed by TP. Combination of both face-to-face and teledermatology in appropriate dermatological conditions could deliver quality care. [6] Doubtful cases can be submitted to ODF like ACAD_IADVL@yahoogroups.com - an E-mail group formed by the members′ of academic societies such as Indian association of dermatologists,′ venereologists, and leprologists to pool expert opinions rapidly and deliver dermatology care in reduced time.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study assessed various feasibility studies of single TT addressing dermatological conditions of general out-patient setting that are diagnosed mostly by spot examination and excluded studies addressing combination of TTs like teledermoscopy. Pigmented skin lesions like melanoma require teledermosopy for their management. The burden of pigmented skin lesions as a community health problem is negligible in India compared to the west. Therefore, this study has significant relevance to Indian context as Indian teledermatology rarely requires teledermoscopy compared to the west. The data analysis of this study suggests basic TTs like SAFT provides best DA. Health-care providers need to plan for appropriate utility of SAFT either alone or in combination with VC to implement and deliver teledermatology care in India.

Acknowledgments

Author is thankful to Dr. Lancy D′Souza, Reader in Psychology, Maharaja′s College, University of Mysore, Mysore, and Karnataka, India for statistical analysis of the data. Mr. Coimbatore Krishnan Muralidharan, Mr. Manjesh Karigowda, and Mr. Avinash Mysore for secretarial assistance involved in this project. Author is thankful to the Indian society of teledermatology (INSTED) and Special interest group (SIG) teledermatology of the Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists (IADVL) and J. S. S. University, Mysore for their constant academic encouragement rendered in completion of this project.

| 1. |

Perednia DA, Brown NA. Teledermatology: One application of telemedicine. Bull Med Libr Assoc 1995;83:42-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Eedy DJ, Wootton R. Teledermatology: A review. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:696-707.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Huntley AC, Smith JG. New communication between dermatologists in the age of the Internet. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2002;21:202-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Braun RP, Vecchietti JL, Thomas L, Prins C, French LE, Gewirtzman AJ, et al. Telemedical wound care using a new generation of mobile telephones: A feasibility study. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:254-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Kanthraj GR. Classification and design of teledermatology practice: What dermatoses? Which technology to apply? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:865-75.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Kanthraj GR. Newer insights in teledermatology practice. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:276-87.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Levin YS, Warshaw EM. Teledermatology: A review of reliability and accuracy of diagnosis and management. Dermatol Clin 2009;27:163-76.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Eminoviæ N, de Keizer NF, Bindels PJ, Hasman A. Maturity of teledermatology evaluation research: A systematic literature review. Br J Dermatol 2007;156:412-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Warshaw EM, Hillman YJ, Greer NL, Hagel EM, MacDonald R, Rutks IR, et al. Teledermatology for diagnosis and management of skin conditions: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:759-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

van der Heijden JP, Spuls PI, Voorbraak FP, de Keizer NF, Witkamp L, Bos JD. Tertiary teledermatology: A systematic review. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:56-62.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Whited JD. Teledermatology research review. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:220-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Holle R, Zahlmann G. Evaluation of telemedical services. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed 1999;3:84-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Thind CK, Brooker I, Ormerod AD. Teledermatology: A tool for remote supervision of a general practitioner with special interest in dermatology. Clin Exp Dermatol 2011;36:489-94.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Henning JS, Wohltmann W, Hivnor C. Teledermatology from a combat zone. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:676-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

See A, Lim AC, Le K, See JA, Shumack SP. Operational teledermatology in Broken Hill, rural Australia. Australas J Dermatol 2005;46:144-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Caumes E, Le Bris V, Couzigou C, Menard A, Janier M, Flahault A. Dermatoses associated with travel to Burkina Faso and diagnosed by means of teledermatology. Br J Dermatol 2004;150:312-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Oliveira MR, Wen CL, Neto CF, Silveira PS, Rivitti EA, Böhm GM. Web site for training nonmedical health-care workers to identify potentially malignant skin lesions and for teledermatology. Telemed J E Health 2002;8:323-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Colven R, Shim MH, Brock D, Todd G. Dermatological diagnostic acumen improves with use of a simple telemedicine system for underserved areas of South Africa. Telemed J E Health 2011;17:363-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Vañó-Galván S, Hidalgo A, Aguayo-Leiva I, Gil-Mosquera M, Ríos-Buceta L, Plana MN, et al. Store-and-forward teledermatology: Assessment of validity in a series of 2000 observations. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2011;102:277-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Ribas J, Cunha Mda G, Schettini AP, Ribas CB. Agreement between dermatological diagnoses made by live examination compared to analysis of digital images. An Bras Dermatol 2010;85:441-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Pak H, Triplett CA, Lindquist JH, Grambow SC, Whited JD. Store-and-forward teledermatology results in similar clinical outcomes to conventional clinic-based care. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:26-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Oztas MO, Calikoglu E, Baz K, Birol A, Onder M, Calikoglu T, et al. Reliability of Web-based teledermatology consultations. J Telemed Telecare 2004;10:25-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Du Moulin MF, Bullens-Goessens YI, Henquet CJ, Brunenberg DE, de Bruyn-Geraerds DP, Winkens RA, et al. The reliability of diagnosis using store-and-forward teledermatology. J Telemed Telecare 2003;9:249-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Krupinski EA, LeSueur B, Ellsworth L, Levine N, Hansen R, Silvis N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and image quality using a digital camera for teledermatology. Telemed J 1999;5:257-63.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Whited JD, Hall RP, Simel DL, Foy ME, Stechuchak KM, Drugge RJ, et al. Reliability and accuracy of dermatologists' clinic-based and digital image consultations. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:693-702.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Silva CS, Souza MB, Duque IA, de Medeiros LM, Melo NR, Araújo Cde A, et al. Teledermatology: Diagnostic correlation in a primary care service. An Bras Dermatol 2009;84:489-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Massone C, Lozzi GP, Wurm E, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Schoellnast R, Zalaudek I, et al. Personal digital assistants in teledermatology. Br J Dermatol 2006;154:801-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Tucker WF, Lewis FM. Digital imaging: A diagnostic screening tool? Int J Dermatol 2005;44:479-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Eminoviæ N, Witkamp L, Ravelli AC, Bos JD, van den Akker TW, Bousema MT, et al. Potential effect of patient-assisted teledermatology on outpatient referral rates. J Telemed Telecare 2003;9:321-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Rashid E, Ishtiaq O, Gilani S, Zafar A. Comparison of store and forward method of teledermatology with face-to-face consultation. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2003;15:34-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Chao LW, Cestari TF, Bakos L, Oliveira MR, Miot HA, Zampese M, et al. Evaluation of an Internet-based teledermatology system. J Telemed Telecare 2003;9:S9-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Lim AC, Egerton IB, See A, Shumack SP. Accuracy and reliability of store-and-forward teledermatology: Preliminary results from the St George Teledermatology Project. Australas J Dermatol 2001;42:247-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

High WA, Houston MS, Calobrisi SD, Drage LA, McEvoy MT. Assessment of the accuracy of low-cost store-and-forward teledermatology consultation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:776-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Zelickson BD, Homan L. Teledermatology in the nursing home. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:171-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Muir J, Xu C, Paul S, Staib A, McNeill I, Singh P, et al. Incorporating teledermatology into emergency medicine. Emerg Med Australas 2011;23:562-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Rimner T, Blozik E, Fischer Casagrande B, Von Overbeck J. Digital skin images submitted by patients: An evaluation of feasibility in store-and-forward teledermatology. Eur J Dermatol 2010;20:606-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Kvedar JC, Menn ER, Baradagunta S, Smulders-Meyer O, Gonzalez E. Teledermatology in a capitated delivery system using distributed information architecture: Design and development. Telemed J 1999;5:357-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Garcia-Romero MT, Prado F, Dominguez-Cherit J, Hojyo-Tomomka MT, Arenas R. Teledermatology via a social networking web site: A pilot study between a general hospital and a rural clinic. Telemed J E Health 2011;17:652-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Crompton P, Motley R, Morris A. Teledermatology-the Cardiff experience. J Vis Commun Med 2010;33:153-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Van der Heijden J. Teledermatology integrated in the Dutch national healthcare system. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:615-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Sun A, Lanier R, Diven D. A review of the practices and results of the UTMB to South Pole teledermatology program over the past six years. Dermatol Online J 2010;16:16.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Vallejos QM, Quandt SA, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Brooks T, Cabral G, et al. Teledermatology consultations provide specialty care for farmworkers in rural clinics. J Rural Health 2009;25:198-202.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Dam TN, Vang E. Teledermatology on the Faroe Islands. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:891-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Bryld LE, Heidenheim M, Dam TN, Dufour N, Vang E, Agner T, et al. Teledermatology with an integrated nurse-led clinic on the Faroe Islands - 7 years' experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:987-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

van der Heijden JP, de Keizer NF, Bos JD, Spuls PI, Witkamp L. Teledermatology applied following patient selection by general practitioners in daily practice improves efficiency and quality of care at lower cost. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:1058-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Nordal EJ, Moseng D, Kvammen B, Løchen ML. A comparative study of teleconsultations versus face-to-face consultations. J Telemed Telecare 2001;7:257-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Taylor P, Goldsmith P, Murray K, Harris D, Barkley A. Evaluating a telemedicine system to assist in the management of dermatology referrals. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:328-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Gilmour E, Campbell SM, Loane MA, Esmail A, Griffiths CE, Roland MO, et al. Comparison of teleconsultations and face-to-face consultations: Preliminary results of a United Kingdom multicentre teledermatology study. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:81-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Loane MA, Corbett R, Bloomer SE, Eedy DJ, Gore HE, Mathews C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical management by realtime teledermatology. Results from the Northern Ireland arms of the UK Multicentre Teledermatology Trial. J Telemed Telecare 1998;4:95-100.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Loane MA, Gore HE, Corbett R, Steele K, Mathews C, Bloomer SE, et al. Preliminary results from the Northern Ireland arms of the UK Multicentre Teledermatology Trial: Is clinical management by realtime teledermatology possible? J Telemed Telecare 1998;4:3-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Lowitt MH, Kessler II, Kauffman CL, Hooper FJ, Siegel E, Burnett JW. Teledermatology and in-person examinations: A comparison of patient and physician perceptions and diagnostic agreement. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:471-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 52. |

Oakley AM, Astwood DR, Loane M, Duffill MB, Rademaker M, Wootton R. Diagnostic accuracy of teledermatology: Results of a preliminary study in New Zealand. N Z Med J 1997;110:51-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 53. |

Loane MA, Gore HE, Corbett R, Steele K, Mathews C, Bloomer SE, et al. Preliminary results from the Northern Ireland arms of the UK Multicentre Teledermatology Trial: Effect of camera performance on diagnostic accuracy. J Telemed Telecare 1997;3:73-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 54. |

Oakley AM, Rennie MH. Retrospective review of teledermatology in the Waikato, 1997-2002. Australas J Dermatol 2004;45:23-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 55. |

Loane MA, Bloomer SE, Corbett R, Eedy DJ, Gore HE, Mathews C, et al. Patient satisfaction with realtime teledermatology in Northern Ireland. J Telemed Telecare 1998;4:36-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 56. |

Tran K, Ayad M, Weinberg J, Cherng A, Chowdhury M, Monir S, et al. Mobile teledermatology in the developing world: Implications of a feasibility study on 30 Egyptian patients with common skin diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:302-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 57. |

Chung P, Yu T, Scheinfeld N. Using cellphones for teledermatology, a preliminary study. Dermatol Online J 2007;13:2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 58. |

Ebner C, Wurm EM, Binder B, Kittler H, Lozzi GP, Massone C, et al. Mobile teledermatology: A feasibility study of 58 subjects using mobile phones. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:2-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 59. |

Massone C, Lozzi GP, Wurm E, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Schoellnast R, Zalaudek I, et al. Cellular phones in clinical teledermatology. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:1319-20.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 60. |

Oakley AM, Reeves F, Bennett J, Holmes SH, Wickham H. Diagnostic value of written referral and/or images for skin lesions. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12:151-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 61. |

Lozzi GP, Soyer HP, Massone C, Micantonio T, Kraenke B, Fargnoli MC, et al. The additive value of second opinion teleconsulting in the management of patients with challenging inflammatory, neoplastic skin diseases: A best practice model in dermatology? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:30-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 62. |

Ríos-Yuil JM. [Correlation between face-to-face assessment and telemedicine for the diagnosis of skin disease in case conferences]. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2012;103:138-43.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 63. |

van der Heijden JP, de Keizer NF, Voorbraak FP, Witkamp L, Bos JD, Spuls PI. A pilot study on tertiary teledermatology: Feasibility and acceptance of telecommunication among dermatologists. J Telemed Telecare 2010;16:447-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 64. |

Hu SW, Foong HB, Elpern DJ. Virtual Grand Rounds in Dermatology: An 8-year experience in web-based teledermatology. Int J Dermatol 2009;48:1313-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 65. |

Kaddu S, Soyer HP, Gabler G, Kovarik C. The Africa Teledermatology Project: Preliminary experience with a sub-Saharan teledermatology and e-learning program. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;61:155-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 66. |

Weinberg J, Kaddu S, Gabler G, Kovarik C. The African Teledermatology Project: Providing access to dermatologic care and education in sub-Saharan Africa. Pan Afr Med J 2009;3:16.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 67. |

Ezzedine K, Amiel A, Vereecken P, Simonart T, Schietse B, Seymons K, et al. Black Skin Dermatology Online, from the project to the website: A needed collaboration between North and South. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;22:1193-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 68. |

Massone C, Soyer HP, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Di Stefani A, Lozzi GP, Gabler G, et al. Two years' experience with Web-based teleconsulting in dermatology. J Telemed Telecare 2006;12:83-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 69. |

Chen TS, Goldyne ME, Mathes EF, Frieden IJ, Gilliam AE. Pediatric teledermatology: Observations based on 429 consults. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:61-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 70. |

Heffner VA, Lyon VB, Brousseau DC, Holland KE, Yen K. Store-and-forward teledermatology versus in-person visits: A comparison in pediatric teledermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:956-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 71. |

Rubegni P, Nami N, Cevenini G, Poggiali S, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Massone C, et al. Geriatric teledermatology: Store-and-forward vs. face-to-face examination. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:1334-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 72. |

Krupinski E, Burdick A, Pak H, Bocachica J, Earles L, Edison K, et al. American Telemedicine Association's Practice Guidelines for Teledermatology. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:289-302.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 73. |

Eminoviæ N, Dijkgraaf MG, Berghout RM, Prins AH, Bindels PJ, de Keizer NF. A cost minimisation analysis in teledermatology: Model-based approach. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:251.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 74. |

Pak HS, Datta SK, Triplett CA, Lindquist JH, Grambow SC, Whited JD. Cost minimization analysis of a store-and-forward teledermatology consult system. Telemed J E Health 2009;15:160-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 75. |

Whited JD, Datta S, Hall RP, Foy ME, Marbrey LE, Grambow SC, et al. An economic analysis of a store and forward teledermatology consult system. Telemed J E Health 2003;9:351-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,642

PDF downloads

2,704