Translate this page into:

A study of severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs with special reference to treatment outcome

Correspondence Address:

K Devi

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Government Medical College, Thrissur, Kerala

India

| How to cite this article: Devi K, George S, Narayanan B. A study of severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs with special reference to treatment outcome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2016;82:239 |

Sir,

The clinical spectrum of cutaneous adverse drug reactions varies widely from a mild self-limiting exanthematous rash to severe life-threatening conditions. A severe cutaneous adverse reaction is defined as a rash that results in serious skin damage/involves multiple organs/requires hospitalization or prolonged hospital stay/causes significant morbidity or death. [1] This group includes acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (also called drug hypersensitivity syndrome), Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Systemic steroids are definitely beneficial in the first two conditions. Although various treatment modalities are found to be useful in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, there is a lack of adequate data to prove their effectiveness. Given this background, we decided to evaluate the clinical and demographic profile, suspected cause and treatment outcome in patients admitted to our hospital with the diagnosis of severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions.

In this retrospective study conducted at Government Medical College, Thrissur, Kerala which is a tertiary care hospital, the treatment records of all patients admitted with a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, drug hypersensitivity syndrome and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis during a 4 year period (January 2009 to December 2012) were analyzed. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis were diagnosed based on standard definitions. [2] The diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity syndrome was based on criteria laid down in the RegiSCAR group diagnosis score. [3] We graded the causality of drug reactions as certain, probable, possible, unlikely, conditional and unclassifiable using WHO-UMC criteria. [4] Those classified as unlikely, conditional and unclassifiable were excluded from analysis.

Thirty seven cases (28 women and 9 men) were included in the study. Their age varied from 18 to 70 years (mean 40.5 years). The majority of the patients (18, 48.6%) were between 21 and 40 years old. Five patients (13.5%) had HIV infection; 14 (37.8%) had central nervous system disorders (primary seizure disorder in 5; tumors and hemorrhage in three each; trauma with seizures in two and hemiplegia in one).

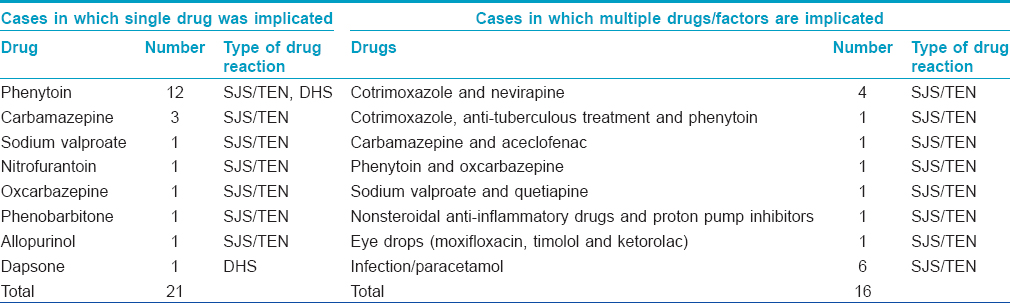

Of our 37 patients, 34 had Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and 4 had drug hypersensitivity syndrome. The discrepancy in the total numbers is because one patient had features of both Stevens-Johnson syndrome and drug hypersensitivity syndrome. There were no patients with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. By the WHO-UMC causality index, 6 were possible cases and 31 were probable cases of cutaneous adverse drug reactions. All the 6 "possible" cases were in the Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis group. The most commonly implicated drug was phenytoin (12 patients), followed by carbamazepine (3 patients) [Table - 1]. Eye drops containing moxifloxacin, timolol and ketorolac were the possible cause in one patient. Multiple drugs were implicated in nine patients.

Among the 34 cases in the Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis group, 24 were classified as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, 6 as toxic epidermal necrolysis and the remaining 3 qualified as Stevens-Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap. In most patients, drugs were the definite triggers; a contributory role for infections could not be ruled out in 6 cases. Phenytoin was the most common causative drug in this group, implicated in 13_ patients. The length of hospital stay varied from 5 to 20 days (average, 11.6 days). Thirty two out of these 34 patients were treated with systemic steroids along with other supportive measures. Dexamethasone was administered intravenously; the initial doses used varied from 4-12 mg per day. The majority (26 out of 32, 81%) received an initial dose ranging between 4-8 mg. Tapering was begun after 1-7 days (average) - 3.4 days). The total duration of corticosteroid treatment was 2-21 days (average, 11.8 days). The cumulative dose of corticosteroid varied from 4 mg to 60 mg of dexamethasone with an average of 31 mg.

Three patients in the Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis group, two of them having toxic epidermal necrolysis and one with Stevens-Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap, died - all of them were cases of "possible" drug reactions where a causative role of infections could not be ruled out. All these patients had fever right from disease onset, did not give any history of drug intake prior to the onset of fever, and skin and mucosal lesions started 1-4 days after the onset of fever. All of them had received paracetamol and one had received aceclofenac for fever. These patients had received high doses of systemic steroids (dexamethasone 12, 16 and 24 mg per day, respectively). The causes of death were septicemia, acute respiratory distress syndrome and sepsis with metabolic encephalopathy. Two of these patients had SCORTEN scores of 2 while the third scored 1.

Among the four patients with drug hypersensitivity syndrome, 3 were due to phenytoin and one due to dapsone. Three of them had maculopapular rashes and one had skin lesions clinically suggestive of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. All four patients had elevated liver enzymes and leukocytosis. One patient had eosinophilia. Steroids were given to all four patients at starting doses of 4-8 mg of dexamethasone/day; their duration of hospital stay was 11-15 days and their mortality was zero.

Phenytoin, the most commonly implicated drug in this study, is a well-known cause of severe cutaneous adverse reactions. [5] Allopurinol, another commonly implicated drug, was causative in one case only. Differences in prescription patterns and population genetics are believed to be responsible for the area-wise variations in the frequency with which drugs cause adverse reactions. [6]

The frequent association with central nervous system disorders in this series may be because of the use of anticonvulsants which are commonly implicated in these types of drug reactions. Two patients in our series had astrocytoma and one had glioblastoma. Malignancies other than central nervous system tumors were not associated. In the EuroSCAR study, 10.6% of cases were associated with malignancy. [7]

Though all cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis had multi-organ involvement, only one of them met the criteria for the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity syndrome based on the RegiSCAR group diagnosis score.

All but two patients in our study were treated with systemic corticosteroids. The complete recovery of all patients of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and two-thirds of the patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap and toxic epidermal necrolysis within a period of 2 weeks indicates the usefulness of systemic corticosteroids in these disorders. The relatively low number of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis compared to Stevens-Johnson syndrome in our study may also indicate an arrest of disease progression at an early phase in response to corticosteroid therapy.

The 3 deaths reported in this study occurred in 3 cases of "possible" drug reactions in which the causative role of infection was not ruled out. The doses of systemic steroids used in these patients were very high (12 mg or more of dexamethasone, intravenously daily).

The treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis includes immediate withdrawal of the culprit drug(s) and management of the patient in a burn care unit with adequate supportive care. Various interventions such as systemic steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide and plasmapheresis have been tried with variable success.

A major histocompatibility class 1-restricted drug presentation leading to the clonal expansion of CD8 cytotoxic lymphocytes may be responsible for the immune reaction leading to Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells are observed to infiltrate the skin lesions of this disorder. Fas-Fas ligand interaction, perforin-granzyme pathway and tumor necrosis factor alpha-tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 interactions are all suggested as mechanisms of keratinocyte death. Granulysin, a cationic cytolytic protein, released by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells is now considered to be the key mediator of disseminated keratinocyte apoptosis. [8] Drugs having an inhibitory effect on the release and effect of granulysin may have an important role in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis group of disorders. Corticosteroids suppress the immunological functions of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells thus preventing keratinocyte death.

The use of systemic steroids in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is much debated. The EuroSCAR study which analyzed the effect of treatment on mortality in this group of disorders suggested that systemic steroids have a beneficial role. The authors hypothesized that the observation of less severe manifestations in the corticosteroid-treated group could be partly attributed to the therapeutic effect of corticosteroids. [7]

In India, where treating Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in burn care units is not usually feasible, systemic corticosteroids may continue to have a major role in management. These powerful and affordable immunomodulatory drugs can arrest disease progression and can be life-saving, if judiciously used.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1272-85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Allanore LV, Roujeau JC. Epidermal necrolysis chapter 39. In: Wolf K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffel DJ, Paller AS, Leffel DJ. Fitzpatrick′s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7 th ed. NewYork: McGraw Hill Companies; 2008.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Roujeau JC, Allanore L, Liss Y, Mockenhaupt M. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs (SCAR): Definitions, diagnostic criteria, genetic predisposition. Dermatol Sin 2009;27:203-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

The Use of the WHO-UMC System for Standardised Case Casualty Assessment. Available from: http://www.who-umc.org/Graphics/24734.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 02].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Patel TK, Barvaliya MJ, Sharma D, Tripathi C. A systematic review of the drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Indian population. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013;79:389-98.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Hung SI, Chung WH, Liou LB, Chu CC, Lin M, Huang HP, et al. HLA-BFNx015801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:4134-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Schneck J, Fagot JP, Sekula P, Sassolas B, Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M. Effects of treatments on the mortality of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: A retrospective study on patients included in the prospective EuroSCAR study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:33-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Chung WH, Hung SI, Yang JY, Su SC, Huang SP, Wei CY, et al. Granulysin is a key mediator for disseminated keratinocyte death in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Nat Med 2008;14:1343-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,234

PDF downloads

2,777