Translate this page into:

Aluminium in dermatology – Inside story of an innocuous metal

Corresponding author: Dr. Vijayasankar Palaniappan, Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital, Madagadipet, Puducherry, India. vijayasankarpalaniappan@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Murthy AB, Palaniappan V, Karthikeyan K. Aluminium in dermatology – Inside story of an innocuous metal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_188_2023

Abstract

Aluminium, the third most abundant element in the earth’s crust, was long considered virtually innocuous to humans but has gained importance in the recent past. Aluminium is ubiquitous in the environment, with various sources of exposure like cosmetics, the food industry, occupational industries, the medical field, transport and electronics. Aluminium finds its utility in various aspects of dermatology as an effective haemostatic agent, anti-perspirant and astringent. Aluminium has a pivotal role to play in wound healing, calciphylaxis, photodynamic therapy and vaccine immunotherapy with diagnostic importance in Finn chamber patch testing and confocal microscopy. The metal also finds significance in cosmetic procedures like microdermabrasion and as an Nd:YAG laser component. It is important to explore the allergic properties of aluminium, as in contact dermatitis and vaccine granulomas. The controversial role of aluminium in breast cancer and breast cysts also needs to be evaluated by further studies.

Keywords

Allergen

alum

alumina

aluminium

Introduction

Aluminium is the third most abundant element in the earth’s crust, the unique properties of this lightweight metal (symbol: Al; atomic number: 13; weight: 26.98; density: 2.7 g/cm3) and its alloys make it a versatile and economical metal with various uses.1 Despite its ubiquity, aluminium was long considered virtually innocuous to humans but has gained importance in the recent past. This review discusses the role of aluminium in various dermatological conditions and its use in diagnostic and therapeutic modalities.

(I) Therapeutic applications of aluminium

1) Anti-perspirant

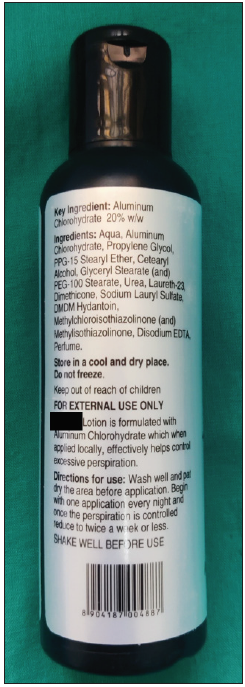

Aluminium salts are effective antiperspirants used in the treatment of axillary and palmoplantar hyperhidrosis of all grades of severity. This aluminium-containing agent can be either prescription based or available over the counter (OTC) whose differences are elucidated in Table 1. The mechanism of action of aluminium chloride hexahydrate (ACH) as an anti-perspirant is elucidated in Figure 1.2 ACH is the most frequently used agent, starting at a lower concentration (10%) for palmar and axillary hyperhidrosis and at a higher concentration (20%) for plantar hyperhidrosis [Figure 2].3 A prolonged administration of this agent is often needed to prevent recanalisation of injured eccrine duct epithelium, thereby providing a sustained hypohidrotic effect.4–6 A randomised half-side trial for assessing the efficacy of aluminium chloride for plantar hyperhidrosis found that clinical score decreased by 38.9% at two weeks from baseline with an additional 7.9% reduction at 6 weeks.7 According to a systematic review, the efficacy of aluminium chloride in axillary hyperhidrosis showed striking difference in Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) response rates in two trials (33% and 72%).8

| S.No | Features | OTC antiperspirant | Prescription based antiperspirant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Composition | Aluminium zirconium trichlorohydrate glycine complexes aluminium chloride hexahydrate (lower concentration upto 12.5%) | 20% aluminium chloride in ethyl alcohol, 12% aluminium chloride in carbonate water, 6.25% aluminium tetrachloride |

| 2 | Irritation | Less irritation due to 80% less production of hydrochloric acid (HCl) | More irritation |

| 3 | Plug formation | Superficial plug formation in eccrine ducts | Deeper plug formation |

| 4 | Frequency of application | Daily application is needed | Every 1–2 days |

| 5 | Absorption in hairy regions | Unaffected | Decreased as the highly charged particles bind to anionic groups on hair surface |

- Mechanism of antiperspirant action of aluminium-based compounds.

- Prescription-based antiperspirant (20% aluminium chlorohydrate).

Aluminium chloride (AlCl3) can also be added to iontophoresis to amplify the anhidrotic effect due to better penetration of aluminium salts into sweat glands.9 The addition of 2% salicylic acid gel to 15% ACH has better efficacy and tolerability due to the keratolytic, antiperspirant and astringent properties of salicylic acid.10

Apart from hyperhidrosis, ACH can also be used for bromhidrosis, transient aquagenic keratoderma, trichomycosis axillaris, epidermolysis bullosa simplex, gustatory hyperhidrosis and local hyperhidrosis associated with eccrine naevi.11 The adverse effects of using aluminium-based antiperspirants include pain, pruritus, hyperpigmentation, irritation, fissuring, scaling and pustules. Factors like high chloride content, low pH and anhydrous alcohol vehicles contribute significantly to the irritant effects of aluminium.12 In mouse models, the use of AlCl3 as an antiperspirant has resulted in axillary granular parakeratosis. It was proposed to be due to aluminium-induced apoptosis resulting in keratinisation arrest at the granular layer of the epidermis.13

2) Topical haemostatic agent

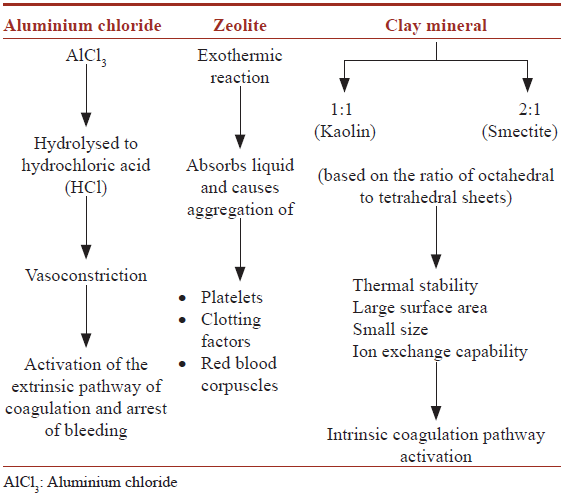

Aluminium chloride (AlCl3) (20–40%) in isopropyl alcohol, ether or glycerol works as an effective chemical haemostatic agent, especially in minor dermatological procedures including skin biopsy. Low cost, easy utility and storage at room temperature attract its usage as a haemostatic agent.14,15 The application of AlCl3 with a cotton-tipped applicator in a twisting motion perpendicular to the skin surface helps establish sufficient haemostasis.14 The advantages of AlCl3 over Monsel solution and electrocautery for haemostasis include less pigmentation and less tissue charring, respectively. The mineral zeolite (microporous crystalline aluminosilicate) and clay minerals such as kaolin and smectite (a combination of octahedral aluminate sheets and tetrahedral silicate in a ratio of 1:1 and 2:1, respectively) have also been used as haemostatic agents.16–19 The mechanisms of action of aluminium chloride, zeolite and clay minerals as topical haemostatic agents are depicted in Table 2.19,20

3) As an astringent

Aluminium acetate (Burow’s solution) is prepared by combining aluminium sulphate, acetic acid, tartaric acid and calcium carbonate. It is an effective astringent and antiseptic used for exudative lesions like eczemas, pompholyx and tinea pedis, especially if vesiculation or maceration is present and for chronic exudative ear infections.21 Aluminium, with a high degree of protein-precipitating properties, alters the ability of proteins to swell and hold water, and draws water out of the cell, leading to the drying up of exudative lesions.22,23 AlCl3, due to its astringent action, has proved efficacious even in post-surgical hypergranulation tissue by its ability to contract and retract the tissues.24

4) Bentonite in contact dermatitis and eczema

Bentonite (colloidal hydrated aluminium silicate) is an insoluble, odourless, white, yellow, pink or grey powder forming a homogenous, viscous gel or colloidal suspension mixed with 10 parts of water. It is incompatible with mineral acids and salts, thus displaying thixotropy.25 It is reported to be effective in hand eczema and diaper dermatitis by causing reduced percutaneous allergen absorption and skin barrier function improvement.26,27

5) Wound healing

Anodic aluminium oxide (AAO) is found to enhance wound healing by acting as a membrane for the firm attachment of cells aiding in the migration and proliferation of epithelial cells.28

6) As sanitizer for controlling transmission of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2)

Bentonite clays carrying a net negative charge and positive charge on edges with high cation exchange capacity act as an excellent adsorbent for SARS-CoV-2 preventing COVID-19 transmission.29

7) Role of aluminium in calciphylaxis and treatment of calcinosis cutis

A close relationship is observed between calcium phosphorus products in plasma and the tendency for ectopic calcification. Administration of aluminium hydroxide (2.8 g/100 mL- 15 to 20 mL four times a day) leads to the formation of insoluble aluminium phosphate, decreasing intestinal absorption of phosphorus and thereby reducing the calcium phosphorus product in plasma.30,31 Aluminium hydroxide (1.8–2.4 g/day) has been used to treat idiopathic calcinosis cutis, calcinosis universalis, calcinosis associated with juvenile dermatomyositis, systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus.32 There are no accepted standard treatment protocols or algorithms for the use of aluminium hydroxide in calcinosis cutis, since the recommendations are based on individual case reports with a low quality of evidence.32

Weenig et al., in a retrospective study, noted a fourfold increase in the risk of developing calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA) with elevated serum aluminium levels (>25 ng/mL).33 A case-control study conducted at the Mayo Clinic identified serum aluminium concentration as a significant factor for calciphylaxis in patients with end-stage renal disease.34 The speculative causes of aluminium overload in calciphylaxis could be attributed to poor urinary excretion of aluminium, low serum transferrin levels resulting in competition for transferrin binding sites between iron and aluminium, and mobilisation of aluminium from bone stores due to high bone turnover in secondary hyperparathyroidism.35–37

8) Role in photodynamic therapy for cutaneous malignancies

Aluminium-chloride-phthalocyanine (AlClPc), a second-generation photosensitising agent, is used for photodynamic therapy with the advantages of high photodynamic efficiency and low cutaneous photosensitivity.38,39 Aluminium (III) phthalocyanine chloride tetra sulphonate (AlPcS4Cl) is another aluminium-based photosensitizer used.40

9) Aluminium adsorbed allergen preparation for honey bee venom allergy

Venom immunotherapy (VIT), a type of allergen-specific immunotherapy or systemic allergen immunotherapy is a highly effective treatment for protecting honey bee venom (HBV) allergic patients from anaphylaxis. In this, aluminium hydroxide (75%) as an adjuvant is mixed with the honey bee venom extract, and the mixture is administered subcutaneously, which protects patients from developing systemic allergic symptoms if re-stung.41 The injections are given in gradually increasing quantities of the allergen until immunological tolerance is achieved.42 Comparative trials show that aluminium hydroxide adsorbed extracts are better tolerated than non-purified extracts, particularly in severe reactions.43

10) Nd YAG and Er Yag laser

Crystals of aluminium garnet and yttrium are doped with neodymium to produce Nd: YAG laser that is used for pigment removal and vascular lesions like telangiectasia, spider veins and hemangioma. Aluminium is a desirable laser host material due to its stability, hardness and optically isotropic nature.44

11) Aluminium oxide crystals for microdermabrasion

Aluminium oxide crystal microdermabrasion (AOCM) was initially developed in 1985 in Italy.45 Aluminium oxide is the most commonly used abrasive in microdermabrasion because of its coarse, uneven surface and chemically inert nature [Figure 3]. AOCM has been found to enhance lipid barrier function through decreased transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and increased hydration in the stratum corneum. The bactericidal property of AOCM has the advantage of treating acne, as acne is associated with bacterial proliferation.46 It has a lower propensity to cause bleeding and allergic contact dermatitis. The hazards associated with AOCM are pain, redness of the eyes, photophobia, epiphora, adherence of crystals to the cornea, and flares of herpes simplex infections.45

- Aluminium oxide crystals used in microdermabrasion.

12) Topical antibiotic

French green clay, rich in iron-smectite, has been used for Buruli ulcers caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans due to its antibacterial properties. It is usually applied in a paste form to the ulcers, left for a week and reapplied again, resulting in wound debridement and regeneration of healthy tissue.17 It was found that the pH and oxidation state buffered by the surfaces of clay minerals control the solution chemistry and redox related events occurring at the bacterial cell wall.17

13) Bentonite as a component of calamine lotion

During the preparation of calamine lotion, bentonite (Al2O3. 4SiO2. xH2O) is added to the powders prior to the addition of water. The main function of bentonite in shake lotions like calamine is to act as a stabiliser/suspending agent.47

14) Aluminium in sunscreens

Aluminium is found to be a component of sunscreens, wherein they help in preventing the agglomeration of titanium dioxide particles. However, due to its pro-oxidant effect, it exaggerates the oxidative damage induced by the chronic use of sunscreens.48

15) Aluminium in friction blisters

A double-blind placebo-controlled trial found that the topical application of 20% ACH applied three times on three different days reduced friction blisters in those involved in hiking.49 The mechanism proposed was reduced sweating by ACH decreases the friction between the skin and the contact surface, thereby reducing the incidence of friction blisters.49

The uses of aluminium in dermatology are summarised in Table 3.

| S.No | Uses | Form of aluminium |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haemostatic agent | Aluminium chloride |

| Zeolite (microporous crystalline aluminosilicate) | ||

| Clay mineral (Kaolin and smectite group) – octahedral aluminate sheets and tetrahedral silicate | ||

| 2 | Antiperspirant | Aluminium chloride hexahydrate |

| Aluminium zirconium trichlorohydrate gly | ||

| Aluminium chloride in ethyl alcohol or carbonate water | ||

| Aluminum tetrachloride | ||

| Aluminium sesquichlorohydrate foam | ||

| Aluminium lactate | ||

| 3 | Astringent (Burow’s solution) | Aluminium acetate |

| 4 | Contact dermatitis | Bentonite (colloidal hydrated aluminium silicate) |

| 5 | Wound healing | Anodic aluminium oxide |

| 6 | As sanitizer for controlling COVID-19 transmission | Bentonite |

| 7 | Calciphylaxis and calcinosis cutis | Aluminium hydroxide |

| 8 | Photodynamic therapy for cutaneous malignancies |

Aluminum-chloride-phthalocyanine Aluminium (III) phthalocyanine chloride tetrasulphonate |

| 9 | Venom immunotherapy for honey bee venom allergy | Aluminium hydroxide |

| 10 | Tattoo, pigment and hair removal | Nd YAG and Er YAG laser |

| 11 | Microdermabrasion | Aluminium oxide |

| 12 | Topical antibiotic | French green clay (Iron smectite) |

| 13 | Stabiliser for shake lotions like calamine lotion | Bentonite |

| 14 | Friction blisters | Aluminium chloride hexahydrate |

| 15 | Finn chamber (patch testing) | Aluminium chloride hexahydrate |

| Aluminum hydroxide | ||

| Aluminum sulphate | ||

| Aluminum lactate | ||

| Aluminum acetate | ||

| Aluminum acetotartrate | ||

| 16 | Contrast agent in confocal microscopy | Aluminium chloride |

Er:YAG: erbium-doped: yttrium aluminum and garnet, Nd:YAG: neodymium-doped: yttrium aluminum garnet

16) Aluminium as an allergen

Contact with aluminium in the environment is inevitable due to the widespread use of aluminium metal as mentioned in Table 4. Aluminium was first identified as an allergen by Hall in 1944 among aircraft workers.50 The “allergen of the year” award for 2022 has been awarded to aluminium by the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS).1 In a systematic review, the prevalence of aluminium contact allergy was found to be 5.6% and 0.4% in children and adults, respectively.51 ACD to aluminium can present as eczematous dermatitis (localised in hands, legs, axilla or widespread systemic contact dermatitis).1 A report of contact urticaria secondary to aluminium-containing coins has been reported.52 The aluminium salts reported to have allergic potential include aluminium chloride hexahydrate, aluminium lactate, alum, aluminium hydroxide, aluminium phosphate and aluminium acetotartrate.53

| S.No | Source of aluminium exposure |

|---|---|

| 1 |

Food industry Processed foods As aluminium foils for food packaging Drinking water As a food additive to prevent caking Colourant |

| 2 |

Cosmetics (as abrasive, anticaking agent, absorbent, buffering agent, corrosion inhibitor, pH adjuster, bulking and opacifying agent) Antiperspirants Sunscreens Tooth paste |

| 3 |

Occupations Mining Welding Scraping metal cycling Construction Sewage treatment Leather tanning Crude oil refining Cracking of petroleum Printing ink Pottery Cement and paints |

| 4 |

Medical Antacids Haemodialysis Measuring radiation exposure Vaccines |

| 5 | Transport |

| 6 | Electronics |

| 7 | Fireproofing |

| 8 | Glass and ceramics |

| 9 | Fumigants and pesticides |

17) Granulomatous conditions

a) Aluminium granuloma

Aluminium salts are used in various vaccines as adsorbents to enhance a specific and long-lasting immune response to antigens [Table 5]. The rationale behind using aluminium as an adjuvant points out theories like “depot theory” (slow elimination of aluminium precipitated antigens) and “antigen targeting theory” (particulate nature of adjuvants favouring phagocytosis and subsequent activation).54 Aluminium salts (aluminium hydroxide, aluminium phosphate and alum) are one of the few adjuvants formulated for the SARS-CoV-2 COVID vaccines. Alum binds with the receptor binding domain (RBD) of S-protein to induce the production of neutralising antibodies, thus offering protection against SARS-CoV-2.55 Aluminium adjuvants mediate inflammation through two pathways, namely NLRP3 inflammasome and NLRP3 independent pathways leading to immune responses and cytokine production.56 The subcutaneous administration of aluminium-containing vaccines is known to produce granuloma by either of the two mechanisms; i) delayed hypersensitivity reaction, and ii) non-allergic reaction to such as direct toxicity. It is estimated that around 1% of all vaccinated children develop vaccine granuloma which appears from 2 weeks and 13 months after injection and persists for an average of 4.6 years.51,57

| S.No | Vaccines containing aluminium as adjuvants |

|---|---|

| 1 | Diphtheria–Tetanus–acellular Pertussis vaccine (DTaP) |

| 2 | Diphtheria–Tetanus–Pertussis vaccine (DTP) |

| 3 | Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine (Hib) |

| 4 | Meningococcal group C conjugate vaccines |

| 5 | Hepatitis A and B vaccines |

| 6 | Human papillomavirus vaccine |

| 7 | Malaria vaccines |

| 8 | Human hookworm vaccine |

| 9 | Anthrax vaccine |

| 10 | Rabies vaccine |

| 11 | Leishmaniasis vaccine |

| 12 | HIV vaccines |

| 13 | SARS-CoV-2 COVID vaccine |

Clinically, it may present as asymptomatic or pruritic erythematous subcutaneous nodules. Associated hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation may be observed. The aluminium-containing Td vaccine has resulted in recurrent interconnected sterile abscesses.58 The exacerbating factors for vaccine granuloma in children include infections, consumption of tin-foiled or canned food and the use of aluminium-containing sunscreens.57 The aluminium granulomas can result in poor quality of life among children.59 The various histopathological features observed in aluminium granuloma include necrobiotic granuloma with surrounding histiocytes, panniculitis, pseudolymphoma and granuloma annulare like patterns.60

b) Tattoo granuloma

Localised aluminium-induced delayed hypersensitivity granulomatous reactions in tattoos have been observed, proposed to be due to delayed type hypersensitivity.61 Granulomatous reactions are observed in 26.3% of the patients getting tattooed.61,62 Similar reactions following blepharopigmentation with aluminium-silicate have been reported.63

c) Foreign body granuloma

Aluminium is one of the inciting agents for foreign body granulomatous reactions in cutaneous sarcoidosis as evidenced by the electron probe microanalysis revealing aluminium peaks in the foreign bodies.64

18) Podoconiosis

Aluminium from the soil that penetrates the skin gets engulfed by the macrophages, resulting in inflammation and fibrosis of the vessel’s lumen thereby blocking lymphatic drainage and resulting in podoconiosis.65,66 A study conducted in the Great Rift Valley in Kenya found that aluminium at a concentration of 10303.82 mg/kg in the soil was significantly associated with the log of expected counts of podoconiosis cases.67

19) Uraemic pruritus

In patients undergoing haemodialysis, exposure to aluminium occurs with the water used for dialysate solution and aluminium-containing phosphate binders. Higher aluminium levels in serum are more associated with uraemic pruritus.68 A ten-fold increase in serum aluminium was associated with a 5.6 fold increase in the risk of developing uraemic pruritus.69 Serum aluminium levels ≥2 µg/dL were significantly associated with a greater risk of uraemic pruritus.69

20) Malignancies

The use of aluminium-containing antiperspirants in the axilla has been implicated in breast cysts and malignancies.70,71 Aluminium by producing DNA alterations, epigenetic effects and interfering with the function of oestrogen receptors can predispose to breast malignancies in the upper outer quadrant.70 The side effects of aluminium in Dermatology are summarised in Table 6.

| S.No | Disease |

|---|---|

| 1 | Allergic contact dermatitis (eczematous dermatitis) |

| 2 | Irritant contact dermatitis |

| 3 | Contact urticaria |

| 4 | Sterile abscesses |

| 5 | Pruritic subcutaneous nodules (vaccine granulomas) |

| 6 | Podoconiosis (Mossy foot) |

| 7 |

Granuloma - Vaccine granuloma - Tattoo granuloma - Foreign body granuloma |

| 8 | Axillary granular parakeratosis |

| 9 | Nephrogenic pruritus |

| 10 | Hyperpigmentation |

| 11 | Hypertrichosis |

| 10 |

Systemic diseases - Breast cancer - Breast cyst - Alzheimer’s disease |

(II) Diagnostic applications

1) Finn chamber

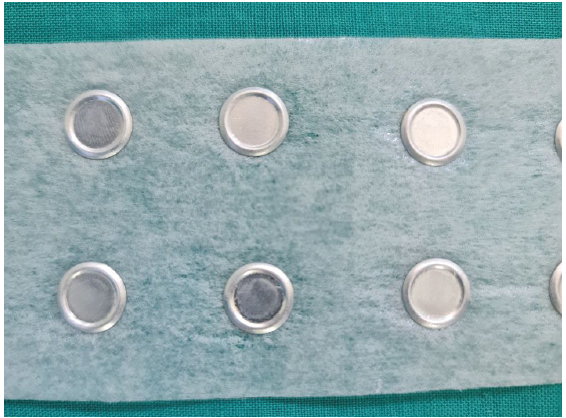

Finn chamber made of aluminium is the most preferred test chamber system in patch testing [Figure 4].72 The amount of aluminium released from an empty Finn chamber corresponds to a skin dose of 0.03% to 0.5% ACH applied in a plastic chamber.1 Aluminium salts, including ACH, aluminium hydroxide, aluminium sulphate, aluminium lactate, aluminium acetate and aluminium acetotartrate, have been used for patch testing instead of elemental aluminium, with petrolatum as the predominant vehicle.53 Studies suggest that patch testing with 10% ACH is better than 2% ACH to detect aluminium allergy, although 2% ACH is sufficient for patch testing in children younger than 7 to 8 years.73 In a study analysing positive patch test results for elemental/metallic aluminium (empty Finn chamber) and 2% ACH in petrolatum in 366 children with vaccine-induced persistent itching nodules, it was found that 31% of children showed positive patch test to 2% ACH with a negative patch test to elemental aluminium.74 Hence, patch testing with elemental/metallic aluminium (empty Finn chamber) is not recommended since it is less sensitive than 2% ACH in petrolatum to diagnose aluminium hypersensitisation.1

- Finn chamber (containing aluminium salts as the predominant vehicle) used in patch testing.

2) As a contrast agent for confocal microscopy

AlCl3 is used as a contrast-enhancing agent in reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM). Tannous et al., utilised 20% AlCl3 as a contrast-enhancing agent in RCM for performing Mohs micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma. The AlCl3-stained tumour cells exhibited intensely bright nuclei with excellent contrast.75 In a study by Flores et al., it was found that in keratinocyte carcinomas, when AlCl3 was applied topically post-surgically to wounds, it provided a consistently enhanced contrast of tumour morphology at a cellular level.76

Conclusion

The role of aluminium and its salts has gained importance over the past few years in various fields of medicine. Aluminium is a vintage metal that has potential applications in various diagnostic and therapeutic armamentariums in dermatology. The emergence of aluminium as an allergen and its use in cosmetic products require special concern for both producers and consumers.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Aluminum-allergen of the year 2022. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2022;33:10-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: A comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:669-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive approach to the recognition, diagnosis, and severity-based treatment of focal hyperhidrosis: Recommendations of the Canadian Hyperhidrosis Advisory Committee. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2007;33:908-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural changes in axillary eccrine glands following long-term treatment with aluminium chloride hexahydrate solution. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:399-403.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topical therapies in hyperhidrosis care. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:485-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment options for hyperhidrosis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:285-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyperhidrosis plantaris - A randomized, half-side trial for efficacy and safety of an antiperspirant containing different concentrations of aluminium chloride. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges J Ger Soc Dermatol JDDG. 2012;10:115-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A systematic evidence-based review of treatments for primary hyperhidrosis. J Drug Assess. ;10:35-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The effect and persistency of 1% aluminum chloride hexahydrate iontophoresis in the treatment of primary palmar hyperhidrosis. Iran J Pharm Res IJPR. 2011;10:641-5.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Aluminum chloride hexahydrate in a salicylic acid gel: A novel topical agent for hyperhidrosis with decreased irritation. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2009;2:28-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disorders of the sweat glands. In: Griffiths CEM, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D, eds. Rook’s textbook of dermatology (9th ed). United Kingdom: Wiley Blackwell; 2016. p. :2455-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical studies of sweat rate reduction by an over-the-counter soft-solid antiperspirant and comparison with a prescription antiperspirant product in male panelists. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:22-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aluminum chloride-induced apoptosis leads to keratinization arrest and granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2020;42:756-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topical hemostatic agents: A review. Dermatol Surg.. 2008;34:431-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topical hemostatic agents for dermatologic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:623-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prehospital use of hemostatic dressings by the Israel Defense Forces Medical Corps: A case series of 122 patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:204-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the medicinal use of clay minerals as antibacterial agents. Int Geol Rev. 2010;52:745-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Application of a zeolite hemostatic agent achieves 100% survival in a lethal model of complex groin injury in Swine. J Trauma. 2004;56:974-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive review of topical hemostatic agents: Efficacy and recommendations for use. Ann Surg. 2010;251:217-28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Advances in topical hemostatic agent therapies: A comprehensive update. Adv Ther. 2020;37:4132-48.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: A comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Soaks and compresses in dermatology revisited. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2023;89:313-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluminum chloride in the treatment of symptomatic athelete’s foot. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:1004-10.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resolution of post-surgical hypergranulation tissue with topical aluminum chloride. SKIN J Cutaneous Med. 2018;2:332-335.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparing the effects of Bentonite & Calendula on the improvement of infantile diaper dermatitis: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142:742-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A skin moisturizing cream containing Quaternium-18-Bentonite effectively improves chronic hand dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:201-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The potential of nanoporous anodic aluminium oxide membranes to influence skin wound repair. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3753-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentonite clay: A potential natural sanitizer for preventing neurological disorders. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:3188-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcinosis cutis in juvenile dermatomyositis: Remarkable response to aluminum hydroxide therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1721-2.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of calcinosis universalis with aluminium hydroxide. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:118-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and treatment of calcinosis cutis: 13 years of experience. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:105.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Calciphylaxis: Natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-79.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria. J Dermatol. 2013;40:336-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The biological speciation and toxicokinetics of aluminum. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102:940-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Competition of iron and aluminum for transferrin: The molecular basis for aluminum deposition in iron-overloaded dialysis patients? Exp Nephrol. 1997;5:239-45.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluminum deposition in the bone of patients with chronic renal failure--detection of aluminum accumulation without signs of aluminum toxicity in bone using acid solochrome azurine. Clin Nephrol. 2002;58:305-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Photodynamic therapy leads to complete remission of tongue tumors and inhibits metastases to regional lymph nodes. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2013;9:811-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of aluminum phthalocyanine chloride and DNA interactions for the design of an advanced drug delivery system in photodynamic therapy. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2018;201:242-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluminium (III) phthalocyanine chloride tetrasulphonate is an effective photosensitizer for the eradication of lung cancer stem cells. R Soc Open Sci. ;8:210148.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Allergen-specific immunotherapy of Hymenoptera venom allergy – also a matter of diagnosis. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2017;13:2467-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14:53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Component-resolved evaluation of the content of major allergens in therapeutic extracts for specific immunotherapy of honeybee venom allergy. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2017;13:2482-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laser oscillations in Nd‐doped yttrium aluminum, yttrium gallium and gadolinium garnets. Appl Phys Lett. 1964;4:182-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aluminum oxide crystal microdermabrasion. A new technique for treating facial scarring. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 1995;21:539-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microdermabrasion. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:277-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluminum: A potential pro-oxidant in sunscreens/sunblocks? Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1216-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of an antiperspirant on foot blister incidence during cross-country hiking. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:202-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occupational contact dermatitis among aircraft workers. J Am Med Assoc. 1944;125:179-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aluminium contact allergy without vaccination granulomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis.. 2021;85:129-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contact urticaria from aluminium and nickel in the same patient. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:303-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Establishing aluminium contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;67:162-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The mechanisms of action of vaccines containing aluminum adjuvants: An in vitro vs in vivo paradigm. Springer Plus. 2015;4:181.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Adjuvants for coronavirus vaccines. Front Immunol. 2020;11:589833.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of immunopotentiation and safety of aluminum adjuvants. Front Immunol. 2013;3:406.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Children with vaccination granulomas and aluminum contact allergy: Evaluation of predispositions, avoidance behavior, and quality of life. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:99-107.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A case of recurrent sterile abscesses following tetanus-diphtheria vaccination treated with corticosteroids. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Unexpected loss of contact allergy to aluminium induced by vaccine. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:286-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluminum-induced granulomas in a tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:903-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skin diseases and tattoos: A five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol.. 2018;153:644-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delayed-hypersensitivity granulomatous reaction induced by blepharopigmentation with aluminum-silicate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:888-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreign bodies in sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:408-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podoconiosis: Non-infectious geochemical elephantiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:1175-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A 24-year-old ethiopian farmer with burning feet. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:583.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soil iron and aluminium concentrations and feet hygiene as possible predictors of Podoconiosis occurrence in Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005864.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The clinical impact of aluminium overload in renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant.. 2002;17:9-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association between serum aluminum level and uremic pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17251.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Underarm cosmetics are a cause of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev.. 2001;10:389-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endocrine disrupters and human health: Could oestrogenic chemicals in body care cosmetics adversely affect breast cancer incidence in women? J Appl Toxicol JAT. 2004;24:167-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patch testing with aluminium Finn Chambers could give false-positive reactions in patients with contact allergy to aluminium. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:407-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patch testing children with aluminium chloride hexahydrate in petrolatum: A review and a recommendation. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:81-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of reactivity to a metallic disc and 2% aluminium salt in 366 children, and reproducibility over time for 241 young adults with childhood vaccine-related aluminium contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:26-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In vivo real-time confocal reflectance microscopy: A noninvasive guide for Mohs micrographic surgery facilitated by aluminum chloride, an excellent contrast enhancer. Dermatol Surg.. 2003;29:839-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intraoperative imaging during Mohs surgery with reflectance confocal microscopy: Initial clinical experience. J Biomed Opt. 2015;20:61103.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]