Translate this page into:

Antibiotic-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): A cross-sectional study

Corresponding author: Dr. Sarita Sasidharanpillai, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Government Medical College, Rohini, Girish Nagar, Nallalom PO, Kozhikode-27, Kerala, India. saritasclt@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sasidharanpillai S, David EM, Jishna P, Khader A, George N, Sabnam CP, et al. Antibiotic-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): A cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2024;90:419. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_507_2022

Dear Editor,

World Health Organisation (WHO) defines antibiotics as ‘medicines used to prevent and treat bacterial infections’.1 Detailed information on drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) induced by antibiotics is mostly limited to anti-tubercular drugs, dapsone and sulphonamides.2

We included consecutive patients diagnosed with antibiotic-induced definite/probable DRESS (according to the RegiSCAR DRESS validation scoring system) and admitted to our dermatology department from January 2011 to January 2020.3,4 Patient profile and disease characteristics, course and outcome were recorded using a pre-set proforma after patient’s written informed consent and Institutional Ethics Committee approval. The data were entered in Microsoft Excel and analysed with SPSS version 18 (Inc IBM company Chicago, United States of America).

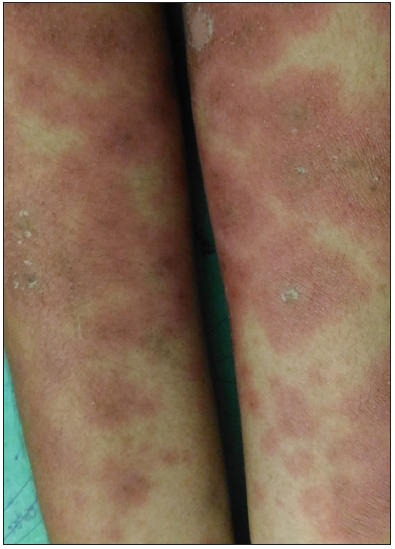

The offending drug was an antibiotic in 35 patients (23.3%, n = 150) with definite/probable DRESS. The age of the study participants ranged from 2 to 67 years (mean 29.7 years, standard deviation (SD) 19.6 years). There were 10 males and 25 females (M: F = 0.4:1). Table 1 shows the offending drugs, latent period and dermatological manifestations [Figures 1–3]. The average latent period was 20.5 days (SD 24.6 days). However, when DRESS induced by dapsone and isoniazid were excluded, the mean latent period was 9.9 days (SD, 13.8 days).

| Offending drugs and indication | DRESS | Mean age and standard deviation in years (range) |

Latent period in days Mean ± standard deviation (range) |

Rash |

Facial oedema n = 33 |

Pedal oedema n = 8 |

Mucosal lesion n = 31 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Probable n = 27 |

Definite n = 8 |

Maculopapular n = 27 |

Purpu ric n = 1 |

Exfoliative dermatitis n = 5 |

Diffuse erythema n = 2 |

Pustular n = 4 |

||||||

|

Amoxicillin (n = 1, 100%), pyoderma |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

10 (10) |

5 (5) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (100%) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (100%) |

|

Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (n = 7, 100%) UTI 2, URI 1, LRI 2, febrile illness 1, dental infection 1 |

4 (57.1%) | 3 (42.9%) |

20.7±21.2 (2–60) |

9.4±9.2 (4–30) |

6 (85.7%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (14.3%) |

0 (0%) |

7 (100%) |

3 (42.9%) |

6 (85.7%) |

|

Azithromycin (n = 3, 100%), UR1 3 |

2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) |

21±23.4 (6–48) |

3 (3) |

2 (66.7%) |

1 (33.3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (33.3%) |

2 (66.7%) |

2 (66.7%) |

3 (100%) |

|

Cefixime (n = 3, 100%), LRI 3 |

3 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

32.3±10 (21–40) |

5.7±1.2 (5–7) |

2 (66.7%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (33.3%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (66.7%) |

|

Cefotaxime (n = 2, 100%), LRI 1, cellulitis 1 |

2 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

27±25.5 (9–45) |

7 (7) |

1 (50%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (50%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (100%) |

|

Cotrimoxazole (n = 3, 100%), UTI 1, prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia 2 |

2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) |

41±17.1 (27–60) |

26.7±33.3 (5–65) |

3 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (100%) |

1 (33.3%) |

3 (100%) |

| Crystalline penicillin (n = 2, 100%), febrile illness 1, LRI 1 | 2 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

8.5±3.5 (6–11) |

3.5±0.7 (3–4) |

2 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (50%) |

2 (100%) |

1 (50%) |

2 (100%) |

| Doxycycline (n = 1, 100%), Hailey-Hailey disease | 1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

42 (42) |

20 (20) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (100%) |

|

Dapsone (n = 7, 100%), BP 2, ITP 2, LCV 1, PLEVA 1, BT 1 |

5 (71.4%) | 2 (28.6%) |

31.3±16.5 (3–49) |

27±5.2 (18–30) |

4 (57.1%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (28.6%) |

1 (14.3%) |

1 (14.3%) |

7 (100%) |

1 (14.3%) |

6 (85.3%) |

|

isoniazid (n = 6, 100%), PTB 2, peritoneal TB 1, scrofuloderma 2, TB meningitis 1 |

5 (83.3%) | 1 (16.7%) |

45±20.7 (16–67) |

52±39.1 (9–120) |

5 (83.3%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (16.7%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

5 (83.3%) |

0 (0%) |

5 (83.3%) |

UTI: urinary tract infection; LRI: lower respiratory tract infection; URI: upper respiratory tract infection; BP: bullous pemphigoid; ITP: idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; LCV: leukocytoclastic vasculitis; PLEVA: pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta; BT: borderline tuberculoid leprosy; TB: tuberculosis; PTB: pulmonary tuberculosis; DRESS: Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.

- Maculopapular rash in a patient with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid–induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.

- Purpuric rash in a patient with azithromycin-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.

- Oedema, erythema and scaling of face in a patient with cefixime-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.

Internal organ involvement was seen in 21/35 (60%) patients [Table 2]. All the 21 patients showed hepatic involvement. Multiple internal organs were affected in 5/35 patients (14.3% – liver and lung in three, liver and kidney in one and liver and spleen in one).

| Offending drug |

Lymphadenopathy (>1 cm in size and affecting two sites) n = 3 |

Internal organ involvement | AEC |

Atypical lymphocytes in peripheral smear n = 16 |

Fatal outcome n = 2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

↑ liver transaminases n = 21 |

Hyperbilirubinaemia n = 4 |

Splenomegaly n = 1 |

Nephritis and renal failure n = 1 |

Pneumonitis n = 3 |

Pleural effusion n = 1 |

700–1499 cells/mm3 n = 10 |

1500 cells/mm3 and above n = 18 |

||||

| Amoxicillin (n = 1, 100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (n = 7, 100%) |

0 (0%) |

5 (71.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

1 (14.3%) |

0 (0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 4 (57.1%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Azithromycin (n = 3, 100%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cefixime (n = 3, 100%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cefotaxime (n = 2, 100%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

| Cotrimoxazole (n = 3, 100%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (66.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (66.7%) |

1 (33.3%) |

1 (33.3%) |

| Crystalline penicillin (n = 2, 100%) |

1 (50%) |

0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

| Doxycycline (n = 1, 100%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (100%) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dapsone (n = 7, 100%) |

2 (28.6%) |

6 (85.7%) |

3 (42.9%) |

1 (14.3%) |

1 (14.3%) |

2 (28.6%) |

1 (14.3%) |

2 (28.6%) | 2 (28.6%) | 4 (57.1%) | 1 (14.3%) |

| Isoniazid (n = 6, 100%) |

0 (0%) |

4 (66.7%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (66.7%) |

2 (33.3%) |

0 (0%) |

AEC: Absolute eosinophil count, ↑: Elevated.

In 7/35 (20%) patients, DRESS was not included in the initial differential diagnosis and was considered only when alternate possibilities were ruled out by meticulous evaluation [Table 3]. In 6/7 cases (85.7%), the initial symptom was a fever that did not respond to treatment or reappearance of fever after an initial resolution or a new onset fever [Table 4].

| Serial no | Indication for treatment, offending drug | The course of disease and subsequent treatment before diagnosing DRESS |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pyoderma leg, amoxicillin for 7 days. | By the 7th day of treatment, the skin lesion had responded, but high-grade fever appeared, suspecting septicaemia, antibiotic was changed to parenteral crystalline penicillin 6th hourly, pruritic maculopapular rash 2 hours after the second dose of crystalline penicillin, penicillin substituted with parenteral amikacin and cetirizine added, facial erythema and oedema after 2 days and persistent fever. |

| 2 | Lower respiratory tract infection and fever, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid combination for 7 days. | Seven days later fever (which had subsided after 1 day of treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid) and pruritic rash, antibiotic was changed to parenteral crystalline penicillin 6th hourly, pedal oedema and facial oedema after three doses of crystalline penicillin. |

| 3 | Lower respiratory tract infection and fever, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid combination for 7 days. | The fever subsided, but reappeared on the 7th day of drug intake. Antibiotics were changed to parenteral ampicillin 6th hourly and pruritic maculopapular rash after the second dose of ampicillin. |

| 4 | Pneumonia, cefotaxime | Fever and respiratory symptoms subsided on the 3rd day of treatment, but fever reappeared on the 7th day, suspecting a superadded infection by the gram-positive organism, cloxacillin was added orally and exfoliative dermatitis with facial erythema and oedema appeared within 12 hours, suspecting cloxacillin-induced exfoliative dermatitis, cloxacillin was withdrawn and prednisolone 30 mg and cetirizine 10 mg added without any improvement, when a thorough evaluation failed to detect any infective foci, cefotaxime withdrawn and patient responded. |

| 5 | Upper respiratory tract infection and fever, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for 5 days. | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid continued for two more days as fever persisted despite 5 days of treatment and then changed to parenteral crystalline penicillin 6th hourly, maculopapular rash, facial oedema and pedal oedema appeared after the 3rd dose of penicillin. |

| 6 | Fever and sore throat, azithromycin | No relief after 3 days of treatment; on the 3rd day, a pruritic, maculopapular rash and facial and pedal oedema appeared, antibiotic was changed to parenteral crystalline penicillin 6th hourly for the next 2 days without any response. |

| 7 | Lower respiratory tract infection, parenteral crystalline penicillin. | The fever subsided on the 3rd day of treatment, but reappeared on the 6th day, penicillin continued; 3 days later pruritic, maculopapular rash appeared, the antibiotic was changed to azithromycin, fever and rash persisted. |

DRESS: Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.

| Offending drug | Initial symptom | Initial diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fever not responding to treatment/reappearing after initial resolution/new onset fever n = 10 |

Rash n = 13 |

Fever and rash together n = 11 |

||

| Amoxicillin clavulanic acid (n = 7) |

2 (28.6%) |

1 (14.3%) |

4 (57.1%) |

Infective aetiology (? Epstein–Barr virus infection) – 3, drug reaction in 4 |

| Amoxicillin (n = 1) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

Infective aetiology not responding to treatment – 1 |

| Azithromycin (n = 3) |

1 (33.3%) |

2 (66.7%) |

0 (0%) |

Infective aetiology not responding to treatment – 1, drug reaction – 2 |

| Cefixime (n = 3) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (100%) |

Drug reaction – 3 |

| Cefotaxime (n = 2) |

1 (50%) |

1 (50%) |

0 (0%) |

Infective aetiology not responding to treatment – 1, drug reaction – 1 |

| Cotrimoxazole (n = 3) |

0 (0%) |

3 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

Drug reaction – 3 |

|

Crystalline penicillin (n = 2) |

1 (50%) |

1 (50%) |

0 (0%) |

Infective aetiology not responding to treatment – 1, drug reaction – 1 |

|

Doxycycline (n = 1) |

0 (0%) |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

Drug reaction – 1 |

|

*Dapsone (n = 7) |

3 (42.9%) |

1 (14.3%) |

2 (28.6%) |

Drug reaction – 7 |

|

Isoniazid (n = 6) |

1 (16.7%) |

3 (50%) | 2 (33.3%) | Drug reaction – 6 |

Two patients (dapsone-induced and cotrimoxazole-induced DRESS, respectively) had a fatal outcome. The fatality rate was 5.7% (2/35) in our cohort of antibiotic-induced DRESS while it was 0.9% (1/115, leflunomide-induced DRESS) in the remaining 115 cases.

Though less discussed, antibiotic-induced DRESS is not uncommon.5 A few studies have identified antibiotics as the most common offenders in DRESS.6,7 A shorter latent period is documented for antibiotic-induced drug reactions including DRESS.5,8,9 Trubiano et al. noted an average latent period of 6 days and 20 days for antibiotic-induced reactions and non-antibiotic-induced reactions respectively.5 This disparity could be due to the shorter duration for which antibiotics are prescribed so that initial exposures do not lead to clinically evident reactions, even in predisposed individuals. However, on repeated exposures, these pre-sensitised individuals develop symptoms within a shorter period. The fact that most of the offenders in our study are commonly prescribed antibiotics supports this possibility. The longer latent period observed in dapsone- and isoniazid-induced DRESS in this cohort is concordant with the fact that these drugs are prescribed for specific indications making prior exposure less likely. A lower mean age with antibiotic-induced DRESS could be attributed to the fact that children are more likely to receive a prescription for antibiotics.10,11

None of our patients had DRESS induced by glycopeptides, despite regular use of vancomycin in our institution, which is inconsistent with current literature.10,12 We noted amoxicillin-clavulanic acid as the most common cause of antibiotic-induced DRESS along with dapsone in accordance with the literature.2,12 It has been proposed that the combination of penicillin and beta-lactamase can trigger DRESS.12

Other clinical and laboratory manifestations noted in our study participants were comparable to most of the previous reports on DRESS.5,11 We observed lymphadenopathy as a less reliable clinical finding in antibiotic-induced DRESS, as many of the infections that necessitated the administration of antibiotic could cause lymphadenopathy. Hence, though seven patients manifested lymphadenopathy, we could assign one point for the same in only three cases as in the remaining four cases (three cases of isoniazid-induced DRESS and one amoxicillin-clavulanic acid–induced DRESS), an alternate cause for the same could not be ruled out.

The diagnosis of DRESS became challenging when the offender turned out to be an antibiotic that was rarely associated with the former, more so when a patient showed either persistent fever or reappearance of fever after an initial resolution, as the initial symptom of DRESS. The possibility of DRESS as a differential diagnosis was considered after meticulous exclusion of the probable infective, autoimmune and neoplastic causes.

We did not attempt a comparison of antibiotic and non-antibiotic-induced DRESS, as 12 different non-antibiotic drugs were identified as offenders. In the latter group, more than 70% of cases were contributed by the anticonvulsants.

There are conflicting reports regarding the prognosis of antibiotic-induced DRESS.4 Whether the higher fatality rate (5.7%) noted for antibiotic-induced DRESS in comparison to non-antibiotic-induced DRESS (0.9%) is limited to dapsone- and cotrimoxazole-induced DRESS remains unclear. The antibiotic-induced DRESS as a whole needs analysis in future, multicentric studies.

Single-centre study design was our major limitation. We evaluated all patients with antibiotic-induced DRESS as one category. We found that antibiotics, other than isoniazid, dapsone and cotrimoxazole, can be potential offenders in DRESS. We suggest that whenever a patient on antibiotics presents with persistent fever/reappearance of fever/new onset fever, DRESS should be considered in the differential diagnoses. An awareness regarding antibiotic-induced DRESS and the short latent period associated with the same is necessary for its prompt diagnosis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance (last accessed 25th May 2022).

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS)/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS): A review of current concepts. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:435-49.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: Does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;56:609-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reply to: Using a diagnostic score when reporting the long-term sequelae of the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1060-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comparative analysis between antibiotic- and non-antibiotic-associated delayed cutaneous adverse drug reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:1187-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: Retrospective analysis of 104 cases over one decade. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130:943-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Vancomycin and DRESS: A retrospective chart review of 32 cases in Los Angeles, California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:973-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) may occur within two weeks of drug exposure: A retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;82:606-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)-results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR) Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:989-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RegiSCAR study group. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): An original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of disease severity in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:266-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial antibiotic-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: A literature review. Eur J Clin Pahrmacol. 2021;77:275-89.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]