Translate this page into:

Clinical, demographic and immunopathological spectrum of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases at a tertiary center: A 1-year audit

2 Department of Histopathology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

3 Department of Immunopathology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

Correspondence Address:

Sanjeev Handa

Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh - 160 012

India

| How to cite this article: De D, Khullar G, Handa S, Saikia UN, Radotra BD, Saikia B, Minz RW. Clinical, demographic and immunopathological spectrum of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases at a tertiary center: A 1-year audit. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2016;82:358 |

Abstract

Background: The subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases are a subset of immunobullous diseases encountered less frequently in the Indian population. There is a paucity of data on the prevalence, demographic and clinicopathological spectrum of various subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases from India. Aim: To determine the demographic and clinicopathological profile of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases in Indian patients, presenting to the Immunobullous Disease Clinic of Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh. Methods: Patients seen from November 2013 to November 2014 who fulfilled the preset diagnostic criteria of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases were identified from case records. Data regarding demographic characteristics, clinical profile, immunopathological findings and treatment were collected from the predesigned proforma. Results: Of 268 cases of autoimmune bullous diseases registered, 50 (18.7%) were subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases. Bullous pemphigoid was most frequently seen in 20 (40%) cases, followed by dermatitis herpetiformis in 14 (28%), mucous membrane pemphigoid in 6 (12%), chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood / linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis in 5 (10%), lichen planus pemphigoides in 3 (6%), pemphigoid gestationis and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita in 1 (2%) case each. None of the patients had bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Limitations: We could not perform direct and indirect immunofluorescence using salt-split skin as a substrate and immunoblotting due to non-availability of these facilities. Therefore, misclassification of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases in some cases cannot be confidently excluded. Conclusion: Subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases are not uncommon in Indian patients. Bullous pemphigoid contributes maximally to the burden of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases in India, similar to that in the West, although the proportion is lower and disease onset is earlier. Dermatitis herpetiformis was observed to have a higher prevalence in our population, compared to that in the West and the Far East countries. The prevalence of other subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases is relatively low. Detailed immunofluorescence and immunoblotting studies on larger patient numbers would help better characterize the pattern of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases and their features in Indian patients.Introduction

Autoimmune bullous diseases are broadly categorized into intraepidermal and subepidermal. Subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases largely comprise of bullous pemphigoid, lichen planus pemphigoides, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigoid gestationis, chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood / linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. They are considered to be infrequent in India compared to the West. The data regarding the demographics and characteristics of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases in India are limited to a few case reports and a limited number of studies on a small number of patients. This study tries to provide preliminary data on the clinical, demographic and immunopathological profile of various subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases as seen over a year in a clinic setting.

Methods

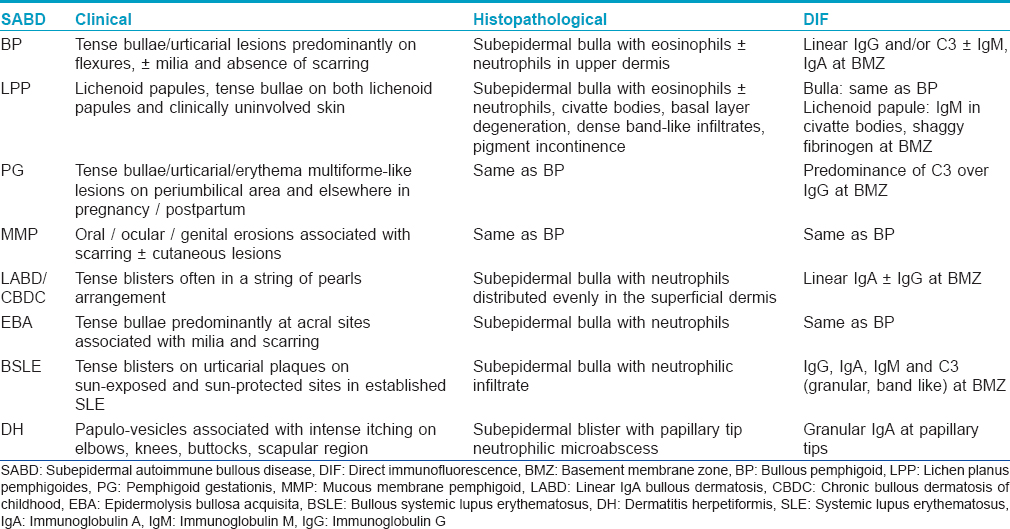

The present study is an audit of patients with subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases registered in the Immunobullous Disease Clinic of Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh seen over a period of 1 year (November 2013 to November 2014). Patients were diagnosed based on a combination of clinical, histopathological and direct immunofluorescence findings according to the criteria detailed for each subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease in [Table - 1]. Demographic details, clinical presentation, associated systemic diseases, histopathology, direct immunofluorescence findings and treatment administered were retrieved from the predesigned proforma of the Immunobullous Disease Clinic. Clinically suspected cases of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases with non-specific histopathology and/or negative direct immunofluorescence results were labeled as indeterminate.

Results

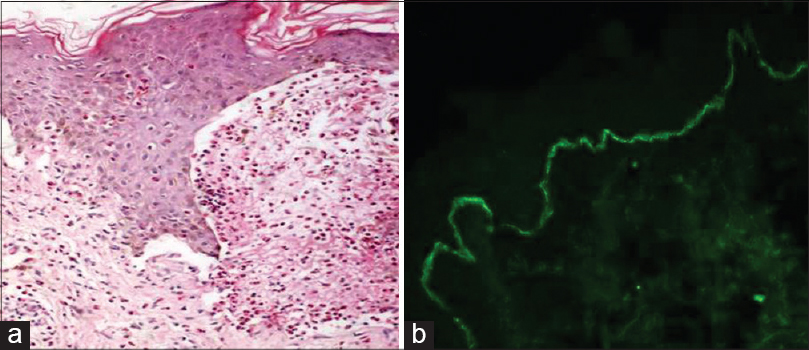

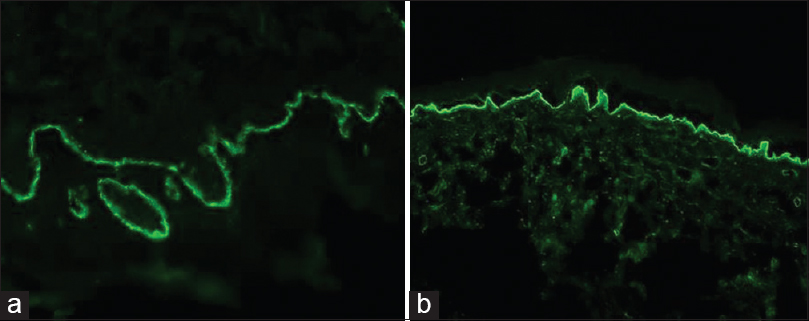

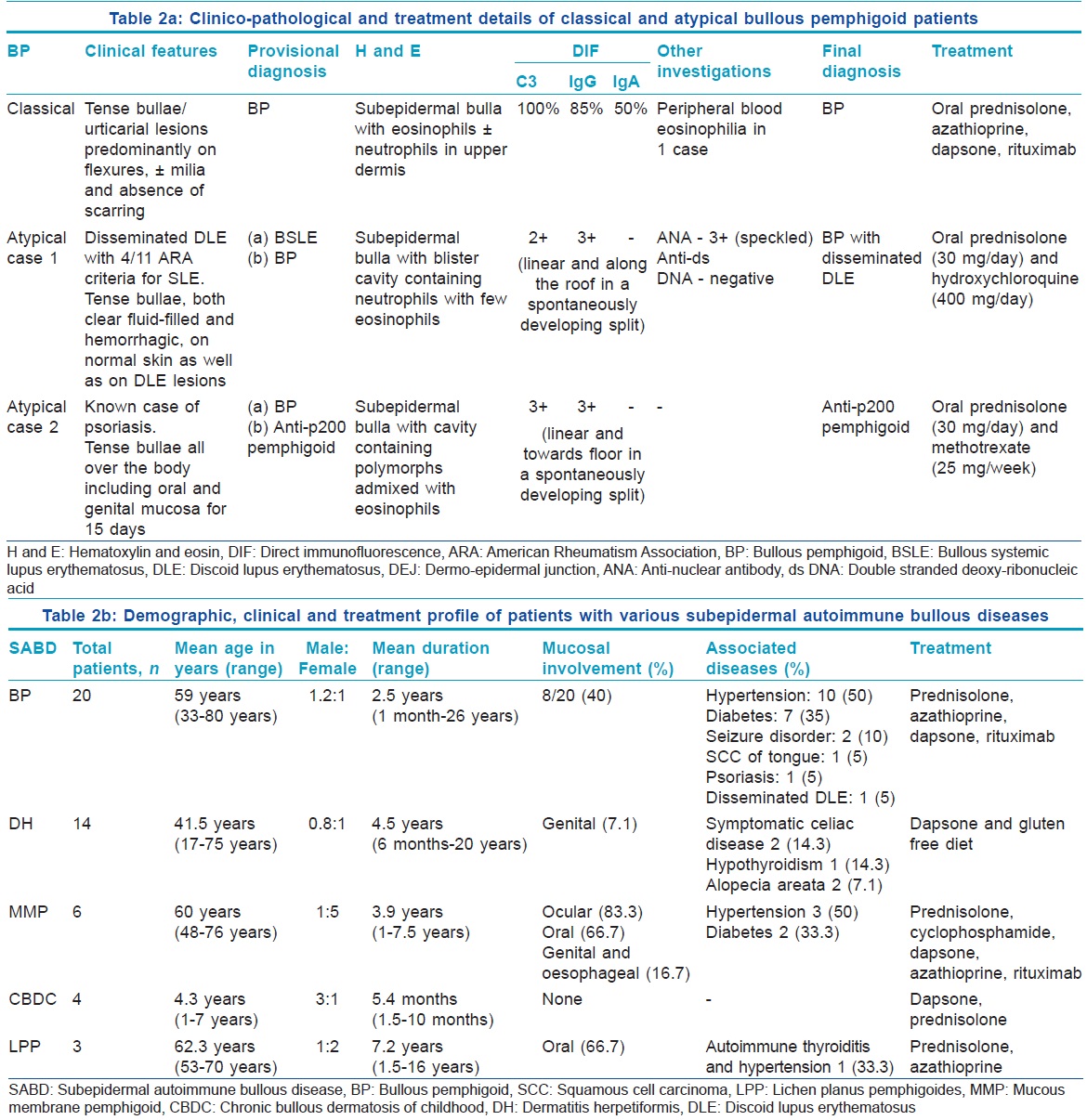

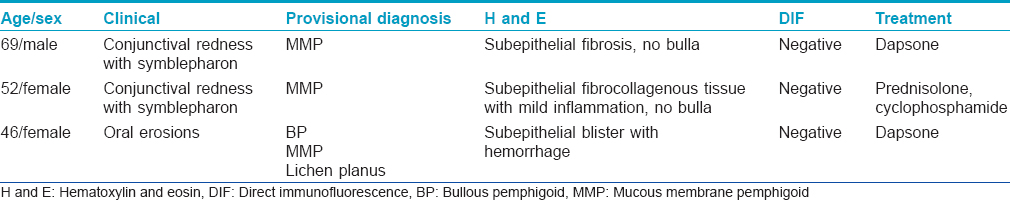

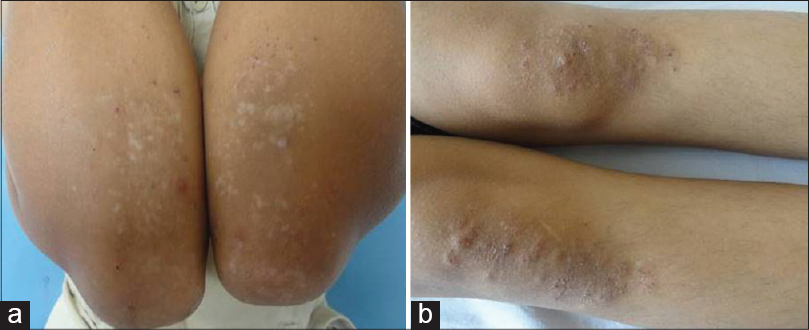

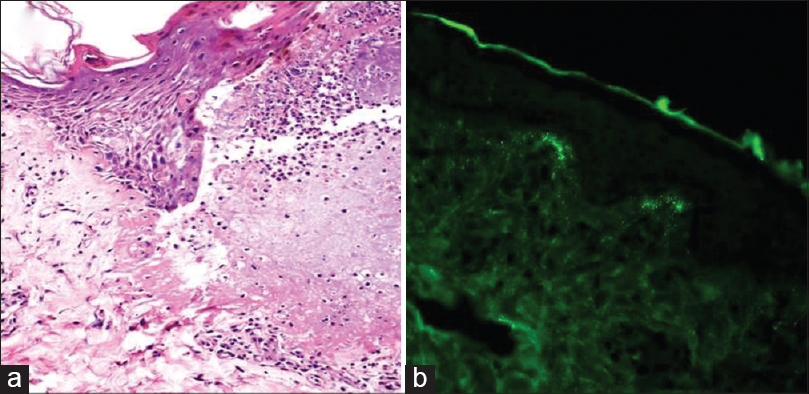

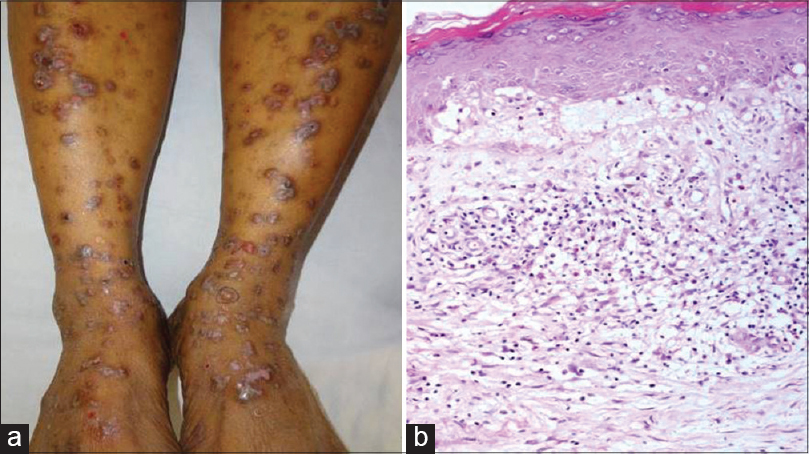

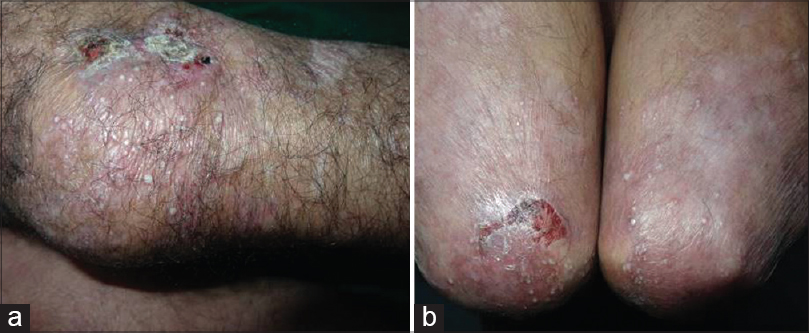

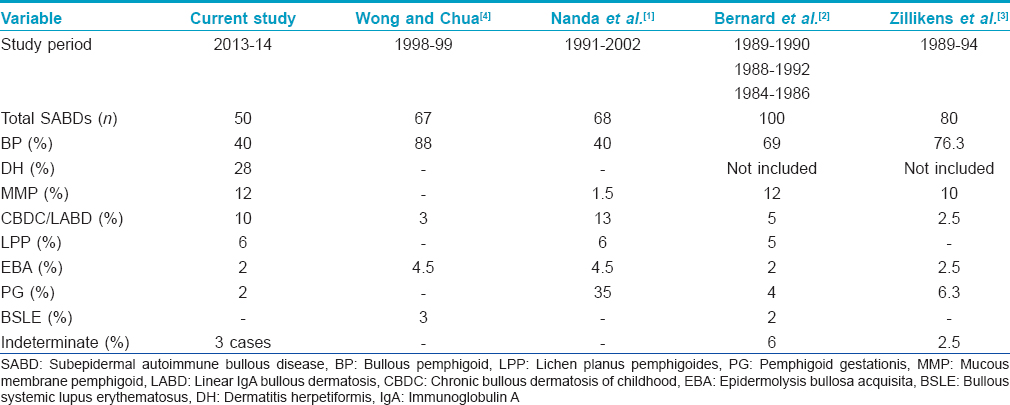

A total of 268 cases of autoimmune bullous diseases were registered in the Immunobullous Disease Clinic during the study period, of which 50 (18.7%) were subepidermal. Bullous pemphigoid was the most common subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease observed in 20 (40%) patients, followed by dermatitis herpetiformis in 14 (28%), mucous membrane pemphigoid in 6 (12%), chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood / linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis in 5 (10%), lichen planus pemphigoides in 3 (6%), and pemphigoid gestationis and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita in 1 (2%) case each. The clinico-pathological and treatment details of classical and atypical bullous pemphigoid patients [Figure - 1], [Figure - 2], [Figure - 3], [Figure - 4] are shown in [Table - 2]a. The demographic, clinical and treatment profile of patients with bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis [Figure - 5] and [Figure - 6], mucous membrane pemphigoid [Figure - 7], chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood and lichen planus pemphigoides [Figure - 8] are summarized in [Table - 2]b. The only woman with linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis was diagnosed clinically as bullous pemphigoid. She also had oral and conjunctival lesions. Her histopathology revealed a subepidermal bulla with an equal proportion of eosinophils and neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence showed linear deposits of immunoglobulin A (4+) and immunoglobulin G (2+) with the absence of C3 at dermoepidermal junction. Based on these findings, her diagnosis was revised to linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis. She showed good improvement with oral prednisolone and dapsone. The clinicopathological and treatment details of indeterminate cases are shown in [Table - 3]. [Figure - 9] depicts the clinical presentation in a patient with epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

|

| Figure 1: (a) Tense bullae overlying urticarial plaques in classical bullous pemphigoid. (b) Hemorrhagic bullae overlying normal skin on the leg in localized pretibial pemphigoid |

|

| Figure 2: (a) Tense bullae and crusted erosions overlying normal skin along with plaques of discoid lupus erythematosus on the extensor surface of the forearms and dorsum of hands. (b) Settled hemorrhagic bullae and crusted erosions healing with hypopigmentation on the legs |

|

| Figure 3: (a) Subepidermal bulla with a cavity containing numerous eosinophils in bullous pemphigoid (H and E, ×100). (b) Direct immunofluorescence depicting C3 positivity in a linear pattern at the dermoepidermal junction |

|

| Figure 4: (a) Direct immunofluorescence showing linear immunoglobulin G deposits at the dermoepidermal junction. (b) Linear immunoglobulin G deposits along the floor of a spontaneously developed split at the dermoepidermal junction in patient with possible diagnosis of anti-p200 pemphigoid |

|

| Figure 5: (a) Grouped excoriated erythematous papules healing with hypopigmentation on the elbows in dermatitis herpetiformis. (b) Similar lesions distributed on the knees |

|

| Figure 6: (a) Subepidermal split with blister cavity rich in neutrophils in dermatitis herpetiformis (H and E, ×100). (b) Direct immunofluorescence showing granular deposits of immunoglobulin A in the dermal papillae |

|

| Figure 7: (a) Desquamative gingivitis in a patient with mucous membrane pemphigoid. (b) Adhesion band between palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva of the left eye |

|

| Figure 8: (a) Tense bulla overlying normal skin on the left lower leg and violaceous plaques showing erosions on bilateral legs in lichen planus pemphigoides. (b) Focal basal cell degeneration, melanin incontinence, subepidermal edema leading to a split with few eosinophils and band-like lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the upper dermis (H and E, ×100) |

|

| Figure 9: (a) Crusted erosions healing with scarring and milia on the knees in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. (b) Elbows showing similar morphology of lesions |

Discussion

There is a paucity of demographic and clinicopathological studies on different subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases from India. The present study describes the demographic and clinico-pathological features of various subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases observed in a clinic setting and their comparison with other countries [Table - 4]. Bullous pemphigoid was the most common subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease which is in accordance with studies from Kuwait, France, Germany and Singapore.[1],[2],[3],[4] However, the proportion of bullous pemphigoid cases was lower compared to that in European countries and Singapore.[2],[3],[4] The mean age at diagnosis was 59 years which was similar to that from Singapore (58.4 years) and slightly lower than that reported by Nanda et al. (65.97 years).[1],[5] On the other hand, studies from Europe have documented a much higher mean age at diagnosis (73.7 and 82.4 years).[2],[3] We observed almost equal gender distribution similar to that reported from Germany and Singapore, while female preponderance was noted in Kuwait (1:6) and France (1:1.5).[1],[2],[3],[5] Majority of our patients (65%) had mild disease, unlike moderate to severe disease reported in 96% of cases from Kuwait.[6] The incidence of mucosal involvement was 40% in the present study which is almost similar to that described from Kuwait (37%), but significantly higher compared to France and Taiwan (24.6% and 12.8%, respectively).[2],[6],[7] We had one patient with a provisional diagnosis of anti-p200 pemphigoid that was associated with psoriasis. A confirmed diagnosis was not possible due to lack of indirect immunofluorescence and immunoblotting facilities. Anti-p200 pemphigoid is a rare subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease that may clinically resemble bullous pemphigoid, linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis or pemphigus herpetiformis and histopathologically shows subepidermal bulla with a collection of neutrophils in the papillary dermis. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin demonstrates autoantibodies binding along the dermal side of the split. Anti-p200 pemphigoid sera react to laminin γ1 on Western blotting in 90% of patients. Psoriasis has been associated in 30% of these cases.[8] Two of our patients had a seizure disorder. An Indian patient having dyshidrosiform bullous pemphigoid associated with parkinsonism has been described.[9] It has been suggested that bullous pemphigoid antigen-1n (neuronal isoform) gets unmasked in the setting of a neurodegenerative disease resulting in antibodies that cross-react with the epithelial form of bullous pemphigoid antigen-1e. Langan et al. reported the development of bullous pemphigoid in 21% of cases with neurological complaints such as stroke, dementia, parkinsonism, epilepsy and multiple sclerosis.[10] A single case of malignancy (squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue) associated with bullous pemphigoid was seen in our study. Fernandes et al. from India reported squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue with lymph node metastasis in a patient of bullous pemphigoid whose disease course paralleled that of malignancy.[11] Chang et al. from Taiwan found internal malignancy in 15.1% of their cases of bullous pemphigoid but the association was not statistically significant when compared with age and gender matched controls.[7] Patients refractory to standard therapies should be evaluated for underlying malignancy. In our study, hypertension (80%) and diabetes (35%) were the most commonly encountered systemic diseases, much higher than the rates from Singapore (21.6% and 14% respectively).[5] An age and gender matched control group should be studied to determine any significant association of bullous pemphigoid with these diseases which are otherwise common in the older population. C3 was the most frequent immunoreactant at the dermoepidermal junction followed by immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin A in our bullous pemphigoid patients. This is in accordance with the study from Singapore which found C3 (87.8%) followed by immunoglobulin G (51.5%) as the most common reactants. In 29.7% of cases, C3 alone was detected in the absence of immunoglobulins and in 8.1%, direct immunofluorescence was negative.[5] Inchara and Rajalakshmi from India reported the sensitivity of direct immunofluorescence to be 82% (23/28) in bullous pemphigoid among a study on 100 patients of immunobullous diseases.[12] Another Indian study evaluated the role of salt-split skin as a substrate for direct and indirect immunofluorescence in 32 histopathologically confirmed cases of bullous pemphigoid. They observed equal sensitivity of direct immunofluorescence on the non salt-split skin and salt-split skin though additional immunoreactants were identified in some cases with salt-split skin. On the contrary, salt-split skin was twice as sensitive as non- salt-split skin for indirect immunofluorescence.[13] The incidence of peripheral blood eosinophilia was low (5%) in our study, in contrast to 22.1% observed in Taiwan.[7]

In the present study, dermatitis herpetiformis was the second most common subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease accounting for 28% of the cases. This was in striking contrast to the studies from Kuwait and Singapore where none of the patients had dermatitis herpetiformis.[1],[4] This may possibly be due to differences in the human leukocyte antigen patterns in various ethnic groups. Furthermore, our results cannot be compared with those from Europe as they had excluded dermatitis herpetiformis among subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases.[2],[3] The mean age of our patients was 41.5 years which was slightly younger than that reported in a clinico-immunopathologic study of 264 dermatitis herpetiformis patients registered at Mayo Clinic (1970–1996).[14] We observed slight female dominance, in contrast to male dominance in the Mayo Clinic study.[14] Autoimmune hypothyroidism and symptomatic celiac disease were seen in 14.3% cases each. This was comparable to the series from Mayo Clinic where celiac disease was present in 12.6% and autoimmune systemic diseases in 22.2% patients (thyroid disorders in 11.1% patients).[14]

Mucous membrane pemphigoid accounted for 12% of subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases. This was comparable to that reported from France and Germany (12% and 10%, respectively) where mucous membrane pemphigoid is the second most frequent subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease after bullous pemphigoid.[2],[3] In contrast to this, only 1.5% cases of mucous membrane pemphigoid were reported from Kuwait and none from Singapore.[1],[4] In the present study, mean age of the patients was 60 years, a slightly lower figure when compared to that described from Europe (69 and 73 years).[2],[3] The female preponderance in our study was similar to that observed in Germany (1:7), although in the French study, males were more frequently affected (1:0.3).[2],[3] We found ocular mucosa to be most frequently affected followed by oral, genital and esophageal mucosa. A study from Mayo Clinic on 81 patients of mucous membrane pemphigoid reported oral lesions in 84%, ocular in 76.5%, genital in 29.6% and esophageal in 7.4% patients.[15] In our study, hypertension and diabetes mellitus were present in 50% and 33.3% patients, respectively and malignancy in none. On the other hand, at Mayo Clinic, malignancy was observed in 14.8% cases though the association was not significant. Diabetes and hypertension were observed in 4.9% cases each.[15]

Although lichen planus pemphigoides was earlier thought to be an expression of coexisting lichen planus and bullous pemphigoid, it is now regarded as a distinct entity. Compared to bullous pemphigoid, it affects a younger age group, has a tendency to involve the lower extremities and has a less severe course. In the present study, lichen planus pemphigoides contributed to 6% of the total subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases. Studies from France, Germany and Singapore did not observe any case of lichen planus pemphigoides.[2],[3],[4] Although mostly idiopathic, lichen planus pemphigoides may be associated with drug intake, phototherapy, hepatitis B/C and internal malignancy. One of our patients had autoimmune hypothyroidism. On histopathology, we found civatte bodies in all three patients while Zaraa et al. described civatte bodies in 16.7% and fibrin in 11.5% patients.[16] The other subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases (pemphigoid gestationis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and bullous systemic lupus erythematosus) were uncommon as observed in similar studies from elsewhere. The limitations of our study were that we could not perform immunofluorescence on salt-split skin and immunoblot analysis which would have helped in further characterization of cases that could not be diagnosed based on histopathology and direct immunofluorescence alone and would have prevented any possible misclassification of the remaining cases.

Conclusion

Bullous pemphigoid is the most common subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease in India as in Western Europe though the proportion, at least in our cohort of patients, seems to be lower, with an earlier age of onset. The second most frequently encountered subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease is dermatitis herpetiformis, in contrast to the Far East and European countries. The other subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases such as mucous membrane pemphigoid, linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis, lichen planus pemphigoides, pemphigoid gestationis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and bullous systemic lupus erythematosus are relatively less common in our patients. Larger studies on the epidemiology and clinico-immunological profile of individual subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases in Indian patients will help in characterizing them better.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Nanda A, Dvorak R, Al-Saeed K, Al-Sabah H, Alsaleh QA. Spectrum of autoimmune bullous diseases in Kuwait. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:876-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Bernard P, Vaillant L, Labeille B, Bedane C, Arbeille B, Denoeux JP, et al. Incidence and distribution of subepidermal autoimmune bullous skin diseases in three French regions. Bullous Diseases French Study Group. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:48-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Zillikens D, Wever S, Roth A, Weidenthaler-Barth B, Hashimoto T, Bröcker EB. Incidence of autoimmune subepidermal blistering dermatoses in a region of central Germany. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:957-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Wong SN, Chua SH. Spectrum of subepidermal immunobullous disorders seen at the National Skin Centre, Singapore: A 2-year review. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:476-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Tham SN, Thirumoorthy T, Rajan VS. Bullous pemphigoid: Clinico-epidemiological study of patients seen at a Singapore skin hospital. Australas J Dermatol 1984;25:68-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Nanda A, Al-Saeid K, Al-Sabah H, Dvorak R, Alsaleh QA. Clinicoepidemiological features and course of 43 cases of bullous pemphigoid in Kuwait. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31:339-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Chang YT, Liu HN, Wong CK. Bullous pemphigoid – A report of 86 cases from Taiwan. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996;21:20-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Goletz S, Hashimoto T, Zillikens D, Schmidt E. Anti-p200 pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71:185-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Behlim T, Sharma YK, Chaudhari ND, Dash K. Dyshidrosiform pemphigoid with Parkinsonism in a nonagenarian Maharashtrian female. Indian Dermatol Online J 2014;5:482-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Langan SM, Groves RW, West J. The relationship between neurological disease and bullous pemphigoid: A population-based case-control study. J Invest Dermatol 2011;131:631-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Fernandes J, Barad P, Shukla P. Association of bullous pemphigoid with malignancy: A myth or reality? Indian J Dermatol 2014;59:390-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Inchara YK, Rajalakshmi T. Direct immunofluorescence in cutaneous vesiculobullous lesions. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2007;50:730-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Satyapal S, Amladi S, Jerajani HR. Evaluation of salt split technique of immunofluorescence in bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002;68:330-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Alonso-Llamazares J, Gibson LE, Rogers RS 3rd. Clinical, pathologic, and immunopathologic features of dermatitis herpetiformis: Review of the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:910-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Hardy KM, Perry HO, Pingree GC, Kirby TJ Jr. Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol 1971;104:467-75.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, Chelly I, El Euch D, Zitouna M, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides : Four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol 2013;52:406-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

7,147

PDF downloads

3,270