Translate this page into:

Clinical profile and virology analysis of hand, foot and mouth disease cases from North Kerala, India in 2015–2016: A tertiary care hospital-based cross-sectional study

2 Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Government Medical College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India

3 Department of Virus Research, Regional Reference Laboratory for Influenza Viruses and ICMR Virology Network Laboratory-Grade-I, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Correspondence Address:

Sarita Sasidharanpillai

‘Rohini,’ Girish Nagar, Nallalom PO, Kozhikode - 673 027, Kerala

India

| How to cite this article: Sabitha S, Sasidharanpillai S, Sanjay RE, Binitha MP, Riyaz N, Muhammed K, Smitha T, Vidya AS, Vaishnavi KV, Saranya TM, Arunkumar G. Clinical profile and virology analysis of hand, foot and mouth disease cases from North Kerala, India in 2015–2016: A tertiary care hospital-based cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2018;84:328-331 |

Sir,

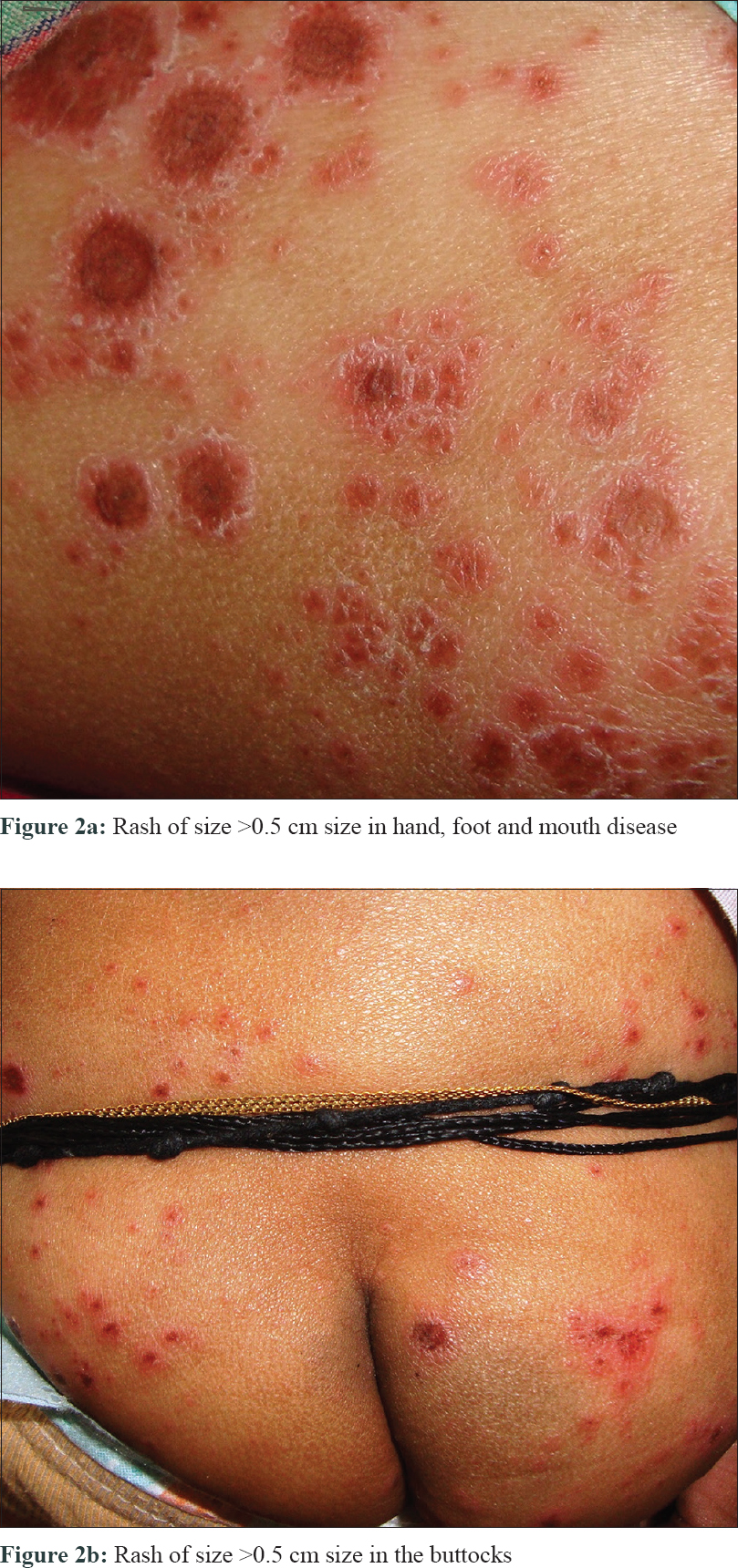

Hand, foot and mouth disease manifests with low-grade fever along with vesicles or papules on oral mucosa, palms, soles and buttocks.[1],[2] Rash affecting face, perioral area and trunk and rash more than 0.5 cm in size are considered as features of atypical hand, foot and mouth disease.[3],[4],[5]

We conducted a study to describe the clinical features and etiology of hand, foot and mouth disease in patients attending the Dermatology Department of Government Medical College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India.

The first 60 patients who attended the Dermatology Outpatient Department of our institution from September 1, 2015 with clinically diagnosed hand, foot and mouth disease were included in the study, after obtaining written informed consent from individual patient (or the guardian in case of children below 18 years). Ethical clearance was obtained from Ethics Committee of our institution and Manipal Academy of Higher Education where the viral study was carried out.

Patients who were diagnosed to have probable or definite drug reaction as per World Health Organization causality assessment and patients showing multinucleated giant cells in Tzanck smear analysis were excluded from the study.[6]

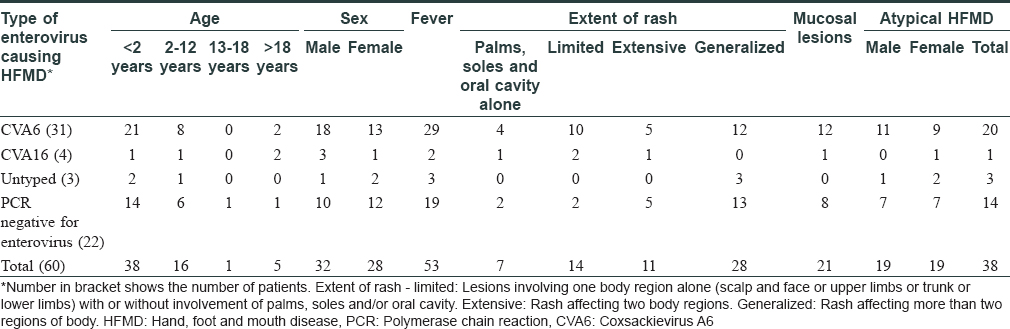

Using a predesigned proforma, data on patient profile and clinical manifestations were collected from each patient. The subjects were classified into those with limited rash, extensive rash and generalized rash [Table - 1]. Those who manifested with rash affecting face, perioral area or trunk and those who presented with skin lesions of size 0.5 cm or more were categorized as atypical hand, foot and mouth disease.[4]

Swabs collected by rupturing intact vesicle with a sterile needle or from oral erosion or posterior pharynx (in the absence of intact vesicle) were transported in viral transport medium for virology workup.[7],[8],[9] The data were analyzed. Thirty eight patients (63.3%) tested positive for enterovirus by real-time polymerase chain reaction [Table - 1]. Serotyping identified Coxsackievirus A16 (4, 6.7%), Coxsackievirus A6 (31, 51.7%) and untyped enteroviruses (3, 5%) as the causative agents [Table - 1]. Age of the study group ranged from 8 months to 34 years with slight male predilection (32 males and 28 females, 1.1:1).

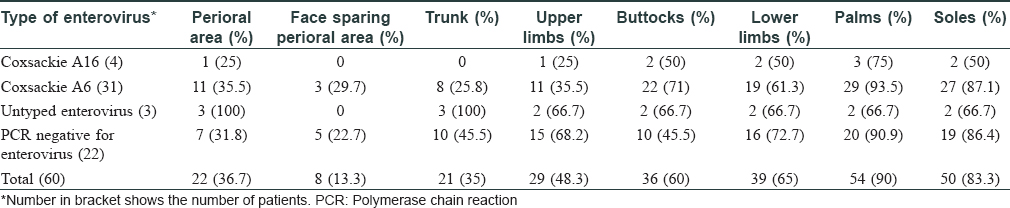

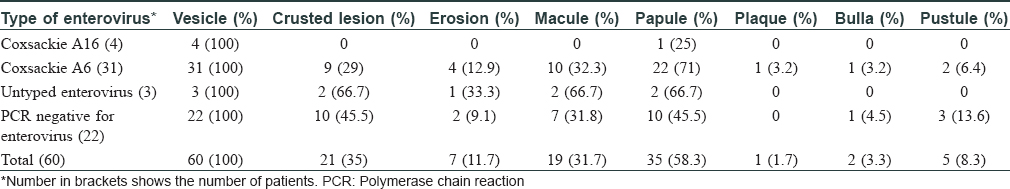

Clinical manifestations documented in the study group were tabulated as shown in [Table - 1], [Table - 2], [Table - 3] [Figure - 1]. Adults manifested more pronounced constitutional symptoms when compared to children. Three patients gave previous history suggestive of hand, foot and mouth disease in the same season. Three children (5%) manifested with hand, foot and mouth disease without any involvement of palms, soles or oral cavity. Generalized rash was documented in 28 patients (46.7%) [Table - 1].

|

| Figure 1: Erythematous macules in the palms in hand, foot and mouth disease |

Thirty eight patients (63.3%) had features of atypical hand, foot and mouth disease [Table - 1], [Table - 2], [Table - 3] and [Figure - 2]a and [Figure - 2]b.

|

| Figure 2 |

Detailed workup including polymerase chain reaction-based study of cerebrospinal fluid for viral infection was within normal limits in two patients who developed seizures, and febrile seizure was diagnosed in the above cases. All patients received symptomatic treatment. The two children who had seizures received clobazam as antiepileptic drug. Complete recovery in 7–10 days was recorded in each case.

This study reports co-circulation of Coxsackievirus A6 and Coxsackievirus A16, with Coxsackievirus A6 being the predominant cause of hand, foot and mouth disease in North Kerala during 2015–2016 which is in variance with the two previous studies from Kerala.[10],[11]

Our finding of Coxsackievirus A6 showing a predilection for children was consistent with other reports from Asia, but contrary to Western data.[1],[4],[12],[13],[14],[15] Though recurrence of hand, foot and mouth disease in the same season is reported earlier (attributed to infection with a different strain formed by genetic recombination), we cannot comment whether the three patients who gave history of previous hand, foot and mouth disease in our study suffered from same virus infection or not because the earlier diagnosis in these cases was not confirmed by virology workup.[16]

Rash sparing palms, soles and oral cavity as observed in some of our patients is reported earlier.[4],[5] The higher percentage of atypical hand, foot and mouth disease in this study could be attributed to the study being conducted in a tertiary care institution.[17]

Nearly one-third of the clinically suspected cases testing polymerase chain reaction negative for pan enterovirus could be due to delay in sample collection, inadequate material for virology workup, the failure to maintain the cold chain during viral transport and inability to detect a new or uncommon enterovirus RNA by the assay. Not collecting throat swab and stool sample in included cases would have contributed to the negative result.

Small sample size and lack of follow-up were the main limitations of our study. By conducting the study in a tertiary referral center, we were unable to gather information on the epidemiological aspects.

To conclude, absence of rash in hands, feet and mouth at the time of presentation does not rule out hand, foot and mouth disease. We recommend continuous monitoring to understand the changing patterns of hand, foot and mouth disease.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the legal guardian has given his consent for images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The guardian understands that names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal patient identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

This study was partially supported by the research grants of Dr. G. Arunkumar from Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi (No. 5/8/7/15/2010-ECD-I and No. VIR/NP/66/2013-ECD-I).

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Xing W, Liao Q, Viboud C, Zhang J, Sun J, Wu JT, et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease in China, 2008-12: An epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:308-18.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Aswathyraj S, Arunkumar G, Alidjinou EK, Hober D. Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD): Emerging epidemiology and the need for a vaccine strategy. Med Microbiol Immunol 2016;205:397-407.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, Susi P, Hyypiä T, Waris M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:1485-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Bian L, Wang Y, Yao X, Mao Q, Xu M, Liang Z, et al. Coxsackievirus A6: A new emerging pathogen causing hand, foot and mouth disease outbreaks worldwide. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2015;13:1061-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Miyamoto A, Hirata R, Ishimoto K, Hisatomi M, Wasada R, Akita Y, et al. An outbreak of hand-foot-and-mouth disease mimicking chicken pox, with a frequent association of onychomadesis in Japan in 2009: A new phenotype caused by Coxsackievirus A6. Eur J Dermatol 2014;24:103-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

The Use of the WHO-UMC System for Standardized Case Causality Assessment. Uppsala: The Uppsala Monitoring Centre; 2005. Available from: http://www.who-umc.org/Graphics/24734.pdf. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 04].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Puenpa J, Chieochansin T, Linsuwanon P, Korkong S, Thongkomplew S, Vichaiwattana P, et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by Coxsackievirus A6, Thailand, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19:641-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Primer for Coxsackie Virus A16 Nucleic Acid Detection, Probe and Kit; 2010. Available from: http://www.google.com/patents/CN101676406A. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 21].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Primer for Enterovirus 71 Type Nucleic Acid Detection, Probe and Kit; 2010. Available from: http://www.google.com/patents/CN101676407A. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 21].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Sasidharan CK, Sugathan P, Agarwal R, Khare S, Lal S, Jayaram Paniker CK, et al. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease in Calicut. Indian J Pediatr 2005;72:17-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Gopalkrishna V, Patil PR, Patil GP, Chitambar SD. Circulation of multiple enterovirus serotypes causing hand, foot and mouth disease in India. J Med Microbiol 2012;61:420-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Robinson CR, Doane FW, Rhodes AJ. Report of an outbreak of febrile illness with pharyngeal lesions and exanthem: Toronto, summer 1957; Isolation of group A Coxsackie virus. Can Med Assoc J 1958;79:615-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Ghosh A, Dutta A, Biswas S, Mandal RK, et al. Mucocutaneous features of hand, foot, and mouth disease: A reappraisal from an outbreak in the city of Kolkata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010;76:564-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Thumjaa A. Case series of hand foot mouth disease in children. Int J Contemp Pediatr 2014;1:14-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Kumar KB, Kiran AG, Kumar BU. Hand, foot and mouth disease in children: A clinico epidemiological study. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol 2016;17:7-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Sarma N. Relapse of hand foot and mouth disease: Are we at more risk? Indian J Dermatol 2013;58:78-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, Zhu CM, Hu YG, Liu QB, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: A retrospective study. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:802046.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

5,203

PDF downloads

2,835