Translate this page into:

Clinical profile of leprosy among domestic and migrant patients diagnosed at a tertiary referral centre in North Kerala: A ten-year retrospective data analysis

Corresponding author: Dr. Nikhil George, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Government Medical College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India. nikhilgeorge027@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: George N, Majeed AP, Sasidharanpillai S, Jishna P, Chathoth AT, Devi K. Clinical profile of leprosy among domestic and migrant patients diagnosed at a tertiary referral centre in North Kerala: A ten-year retrospective data analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:422-5.

Sir,

Despite India achieving the status of 'elimination of leprosy as a public health problem', pockets of endemicity exist within the country. In the era of migrant labour and population movement, this raises concerns regarding the success of national leprosy eradication programme.

Leprosy is highly endemic in the states of Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Odisha.1,2 In recent years, Kerala has witnessed a steady influx of migrant labourers from these areas for job opportunities, who have contributed significantly to the economy of the state.3 In this retrospective analysis (2009-2018), we compared the clinical profile of leprosy among domestic cases and migrant patients diagnosed at our centre. Migrant population includes individuals from other states residing in Kerala for less than eight years.

We reviewed the physical case-records of patients who received leprosy treatment from our institute as per the World Health Organization criteria.4 We included defaulters and patients with relapse, and excluded incomplete case records. Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained.

Using a pre-set proforma, we collected information on patient demography, clinical profile, laboratory parameters and treatment details (paucibacillary or multibacillary regimen as per the World Health Organization recommendation).4 As per institutional policy, all patients underwent slit skin smear examination (from ear lobe, from representative skin lesion and normal skin) for acid-fast bacilli. All patients with skin lesions underwent a skin biopsy. We categorized the disease in each patient based on the Indian Association of Leprologists classification.5

We defined relapse as the reoccurrence of disease at any time after completing the full treatment course.6 Defaulter indicated any paucibacillary or multibacillary patient who had skipped treatment for more than three and six months, respectively.7 The patients who completed their six-month paucibacillary treatment within nine months and 12-month multibacillary treatment within 18 months and 24-month multibacillary treatment within 36 months were considered adequately treated.4,8 Grade 2 disability at presentation was noted in each case.9

The data was statistically analysed by SPSS Inc. IBM company version 16 Chicago, SPSS Inc. (United States of America), using appropriate tests. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

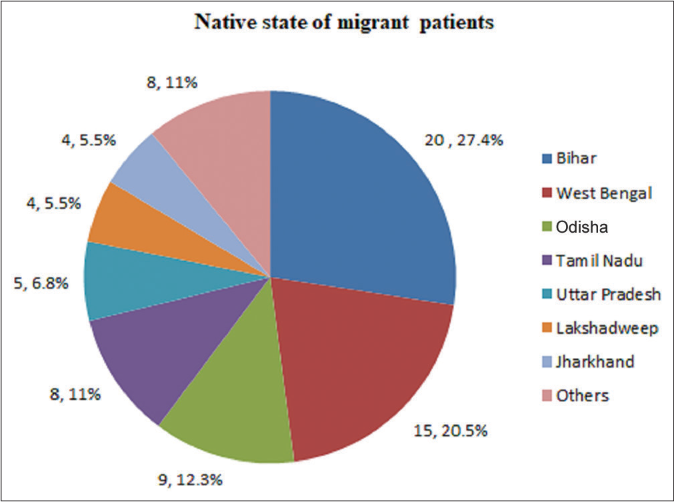

We reviewed the case records of 705 patients and found 73 [10.4%, Figure 1] migrant cases. Their mean duration of stay in the state was 17.1 ± 14.1 months. All migrant patients worked as manual labourers.

- Native states of migrant leprosy patients diagnosed at a tertiary referral centre in North Kerala

The most common age-group affected among domestic cases was 31–45 years (mean, 39.9 ± 16.7 years), compared to 16–30 years (mean, 28.3 ± 1 years) among the migrants [Table 1]. Male-to-female ratio among domestic and migrant patients was 1.9:1 and 17:3.1, respectively (P< 0.001).

| Age | Domestic cases | Migrant cases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males, n=415 |

Females, n=217 |

Total, n=632 |

Males, n=69 |

Females, n=4 |

Total, n=73 |

|

| 15 years or below | 28 6.7% |

15 6.9% |

43 6.8% |

2 2.9% |

0 0% |

2 2.7% |

| 16–30 years | 104 25.1% |

59 27.2% |

163 25.8% |

49 71% |

3 75% |

52 71.2% |

| 31–45 years | 120 28.9% |

74 34.1% |

194 30.7% |

11 15.9% |

0 0% |

11 15.1% |

| 46–60 years | 103 24.8% |

61 28.1% |

164 25.9% |

6 8.7% |

0 0% |

6 8.2% |

| 61–75 years | 55 13.3% |

6 2.8% |

61 9.7% |

1 1.4% |

1 25% |

2 2.7% |

| >75 years | 5 1.2% |

2 0.9% |

7 1.1% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

Thirty five (5.5%) domestic cases provided family history of leprosy, while no migrant patient reported any affected family member.

The mean duration of disease was 18.3 ± 23.5 months (range 2 weeks to 108 months) and 18.6 ± 18.5 months (range 2-120 months) in domestic and migrant patients, respectively.

Among domestic patients, 8.4% (53/632) were cases of leprosy relapse. None of the migrant patients had received adequate treatment for leprosy in the past. Eleven (11/632, 1.7%) domestic and three (3/ 73, 4.1%) migrant patients had defaulted treatment in the past.

Frequency of lepromatous leprosy was significantly higher in migrant patients [P = 0.04, Table 2] and they required multibacillary treatment more frequently (95.9% [70/73] migrants vs. 73.3% [463/632] domestic patients, P < 0.001).

| Leprosy patients | Neuritic | Indeterminate | TT | BT | BB | BL | LL | PB | MB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic cases, n=632 | 84 13.3% |

24 3.8% |

22 3.5% |

385 60.9% |

5 0.8% |

53 8.4% |

59 9.3% |

169 26.7% |

463 73.3% |

| Migrant cases, n=73 |

11 15.1% |

0 0% |

1 1.4% |

41 56.2% |

1 1.4% |

6 8.2% |

13 17.8% |

3 4.1% |

70 95.9% |

| P-value | 0.81 | 0.16 | 0.5 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.96 | 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

TT: Tuberculoid leprosy, BT: Borderline tuberculoid leprosy, BB: Mid-orderline leprosy, BL: Borderline lepromatous leprosy, LL: Lepromatous leprosy, PB: Paucibacillary, MB: Multibacillary

Baseline grade 2 disability was significantly higher in migrants (43.8%, 32/73) compared to domestic patients (25.9%, 164/632) and the difference was significant (P = 0.002).

One hundred and thirty two (26.3%) among the 502 at risk domestic patients and 17 out of the 61 (27.9%) at risk migrant cases developed Type 1 lepra reaction. Twenty four out of the 112 domestic patients (21.4%) and three out of the 19 migrant patients (15.8%) at risk for Type 2 lepra reaction manifested the same. The differences were not significant.

78.6% domestic patients successfully completed multidrug therapy from our centre, almost double the migrant patients (39.7%), 21.4% (135/632) domestic patients and 44 (60.3%) migrant patients opted for treatment from nearby institutions and their native places respectively.

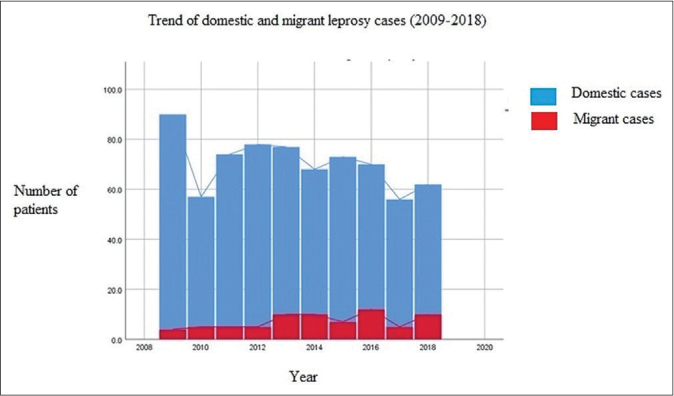

In course of time, the proportion of migrant patients increased [Figure 2], but no significant difference was noted between the correlation coefficients of total leprosy cases in domestic population and migrant population with respect to year (Z=1.72).

- Trend of domestic and migrant leprosy cases attending a tertiary referral centre in North Kerala over a period of ten years (2009–2018). Blue line represents the trend line in domestic leprosy cases. Red line represents the trend line migrant leprosy cases

Male predilection and lower mean-age of migrant patients may be attributed to migration of young, male unskilled workers to the state for employment.

Lack of family history among migrant patients possibly indicates their reluctance to reveal family details.

Often the migrant labourers are forced to reside in overcrowded apartments to reduce the living expenses and this might have resulted in significantly higher lepromatous cases, compared to domestic patients10 (P = 0.04). However, the accurate living conditions of study-participants could not be assessed from case records.

Delayed diagnosis might have resulted in higher proportion of migrant cases requiring multibacillary treatment. Although the mean interval between onset of symptoms and diagnosis was comparable in domestic and migrant cases (approximately 18 months in both), this fails to serve as a reliable indicator of diagnostic delay. Leprosy, being an asymptomatic disease till late stages, often remains unnoticed by the patient for a long time. The significantly higher baseline Grade 2 disability (considered as the gold standard for diagnostic delay in leprosy) among migrant patients further reiterates delayed diagnosis.9 The reluctance of a migrant worker to access medical aid in an unfamiliar area, especially forsaking one day’s salary might have contributed to this delay.

About 60% migrant patients opted to continue treatment from their native place, possibly to avoid discrimination at their work-places.

Significantly higher frequency of lepromatous leprosy among migrant workers and the rise in number of migrant cases over the ten-year study period point to the need to identify vulnerable groups for early diagnosis and treatment.

Retrospective study design, selection bias and lack of information regarding living conditions of patients were our main limitation. Besides, no data was available whether patient migrated alone or with family, and the rural-urban shift.

We must ensure better living conditions and arrange regular health check-up and leprosy detection camps for vulnerable population (like migrant labourers), and link all peripheral health centres (to avoid treatment default) to ensure the success of the National Leprosy Eradication Programme.

Declaration of patient consent

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Available from: https://dghs.gov.in/content/1349_3_NationalLeprosyEradicationProgramme.aspx [Last accessed on 2022 Jan 30]

- Leprosy: The challenges ahead for India. J Skin Sex Transm Dis. 2021;3:106-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inclusion of interstate migrant workers in Kerala and lessons for India. Indian J Labour Econ. 2020;63:1065-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Technical Report Series No. 874 In: Seventh Report. Expert Committee on Leprosy. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998.

- [Google Scholar]

- The consensus classification of leprosy approved by the Indian Association of Leprologists. Lepr India. 1982;54:17-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Leprosy Eradication Programme. Ch. 8. Relapse. Directorate of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi. Available from: http://nlep.nic.in/training.html [Last accessed on 2020 Nov 11]

- [Google Scholar]

- National Leprosy Eradication Programme. Ch. 6. New Delhi: Management of Leprosy Directorate of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Available from: http://nlep.nic.in/training.html [Last accessed on 2020 Nov 11]

- [Google Scholar]

- Implementing Multiple Drug Therapy for Leprosy In: Oxfam Practical Health Guide No. 3 (4th ed). Oxford: Oxfam; 1988.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Leprosy Eradication Programme. Ch. 9. New Delhi: Disability and Management Directorate of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Available from: http://nlep.nic.in/training.html [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 14]

- [Google Scholar]

- Socio-economic conditions of migrant labourers-An empirical study in Kerala. Indian J Appl Res. 2015;5:43-8.

- [Google Scholar]