Translate this page into:

Cutaneous acrometastasis from an undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma with giant cells

Corresponding author: Dr. Alex Viñolas Cuadros, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital of Salamanca, Paseo de San Vicente, 58 – 182, 37002, Salamanca, Spain. avinolascuadros@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Cuadros AV, Riesco MR, Curto CR. Cutaneous acrometastasis from an undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma with giant cells. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:571-3.

Sir,

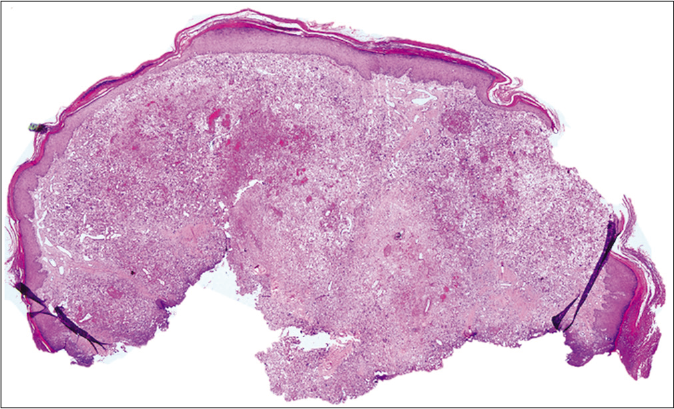

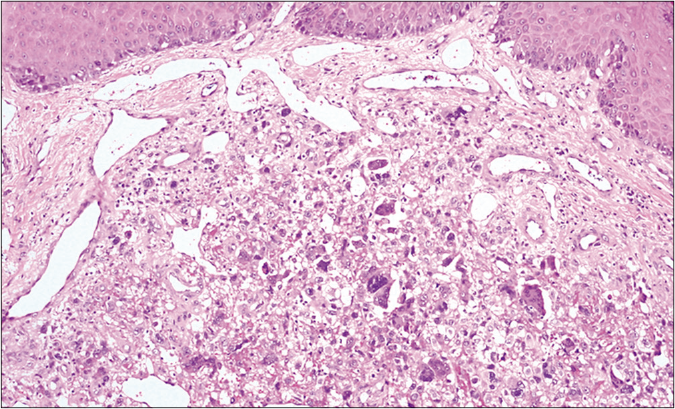

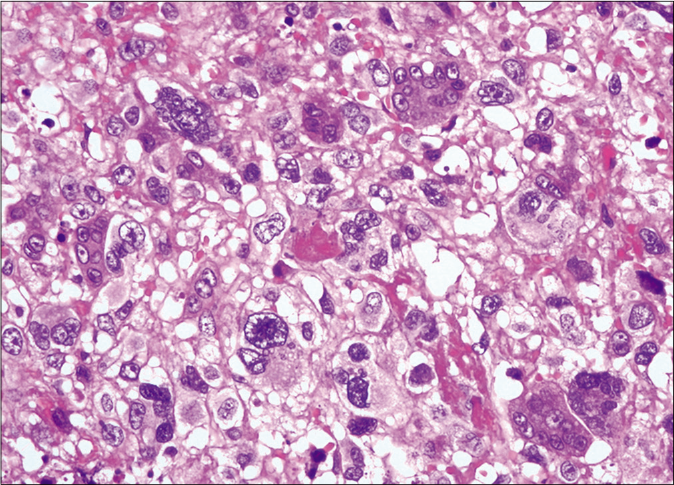

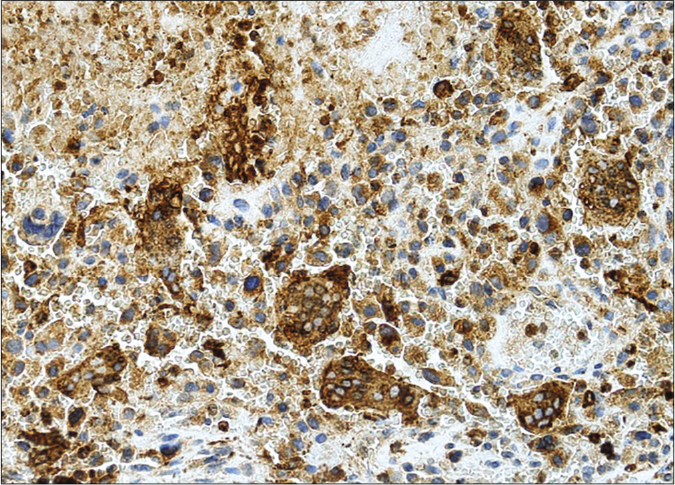

We present a case of a 56-year-old man who underwent amputation in July 2017 for an undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma affecting his left foot. Follow-up computed tomography scan in September 2017 showed bilateral pulmonary metastases and several chemotherapy regimens were required due to progression of the disease. One year later the patient was referred to dermatology for a painful periungual lesion of two months duration, with 1.2 centimeters in diameter, located on the fifth finger of his right hand. It had an angiomatous appearance and history of bleeding on trivial local trauma was reported [Figure 1]. A biopsy was performed under clinical suspicion of a pyogenic granuloma. Microscopic examination revealed a multinodular tumor with hemorrhagic and necrotic areas located in dermis [Figure 2a], consisting of highly pleomorphic and anaplastic medium-sized mononuclear cells [Figure 2b] and multinucleated giant cells [Figure 2c]. Scarce spindle cells were seen on the periphery of the lesion without storiform pattern. Vascular invasion was observed. There was minimal non-specific and patchy staining for actin and for VE-1 (BRAF), with negative mutation for said proto-oncogene in complementary studies. Immunohistochemically, negativity was observed for cytokeratins (AE1/AE3), melanocytic markers (HMB45 and Melan-A), CD31, D2-40 and CD1a. The giant cells and scattered mononuclear cells were positive for CD68 [Figure 2d]. It had a high mitotic index (almost 35%). The features were similar to those of the primary tumor and the lesion was diagnosed as a metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma with giant cells. Dacarbazine treatment was initiated (250 mg/m2/day as a continuous infusion for 4 days every 3 weeks), achieving a complete remission of the cutaneous metastasis [Figure 3]. Three months later the initial lesion reappeared [Figure 4a] along with additional ones [Figure 4b]. He died 10 months after the onset of the acral cutaneous metastasis.

- Angiomatous periungual nodule on the fifth finger of the right hand masquerading as pyogenic granuloma

- A metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma involving the full thickness of the dermis (hematoxylin and eosin, ×40)

- A mix of pleomorphic atypical cells haphazardly arranged (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100)

- Scattered multinuclear giant cells (hematoxylin and eosin, ×400)

- Strongly positive CD68 in multinucleated giant cells and in scattered mononuclear cells (CD68 Antibody and hematoxylin counterstain, ×200)

- Complete remission of the lesion after chemotherapy treatment

- Reappearance of the initial periungual lesion 3 months after chemotherapy

- Newly developed dome-shaped angiomatous lesions on the right palm

Soft tissue sarcomas are infrequent, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas with giant cells (historically referred as giant cell-rich malignant fibrous histiocytoma) are extremely rare (no more than 5% of adult soft tissue sarcomas).1,2 Their main histological feature is the abundance of large multinucleated giant cells that resemble osteoclasts. The remaining cell population is constituted by homogeneous round to polygonal mononuclear cells and fusiform cells in different proportions.1 It is considered a high-grade malignancy tumor. Local destruction, distant metastases and death by the disease within a short interval have been reported. Their metastases preferentially spread to the lungs (> 80%) but also lymph nodes, bone and soft tissues have been documented.1 It should not be confused with the giant cell tumor of soft tissue, which has a low malignant potential, is superficially located and lacks cytological atypia.3 Also, giant cells can be seen in many other malignant neoplasms as in osteosarcomas, endometrioid carcinomas, extraskeletal osteosarcomas, undifferentiated urinary tract carcinomas and malignant melanoma, among other less frequent tumors.2,4 So, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma essentially represents a diagnosis of exclusion after exhausting all the morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostic modalities.2,4

In general, cutaneous metastases occur in 0.6–10.4% of patients with malignant neoplasms. The most frequent metastasizing primary tumors are the lung (41%), the kidney (11%) and the breast (9%).5 Metastatic spread to the digits is exceptional (0.1% of total metastases) and both the fingers (86%) and the toes (6%) can be affected.6 Commonly, bone involvement occurs firstly and extension to skin is later produced. Acral cutaneous metastases are generally produced by hematogenous spread and therefore the prognosis is poor, the median survival time being 1 to 34 months.6 Cutaneous metastases in relation with sarcomas are rare (0.26% of all sarcoma cases), leiomyosarcoma being the commonest comprising 43% of all sarcomas with cutaneous metastases, while those caused by undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma constituted up to 6% of them, with only seventeen cases reported in English literature to our knowledge, where only two were located on the toes.7-12

Cases of angiomatous form that simulate pyogenic granuloma have been described in relation to cutaneous metastases of renal, hepatic and thyroid carcinomas.5 Acral cutaneous metastases tend to present as an erythematous and intensely painful swollen finger.6 The appearance of cutaneous metastases from undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been described in the literature as an ulcerated or skin-colored nodule with associated swelling.7-10,12 Although we could not find cases simulating a pyogenic granuloma-type tumor, Gounder et al. reported a primary case in the palpebral conjunctiva that actually resembled one.13

An exceptional metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma with giant cells to the acral skin is presented, with a clinical appearance of a benign vascular tumor. This case highlights the importance of suspecting a cutaneous metastasis for any rapidly growing lesion in oncologic patients, even if they are benign in appearance. In our patient the cutaneous metastases objectified an early resistance to the different treatments. Its evolution confirms the unfortunate prognosis of cutaneous metastases, especially when they present hematogenous seeding.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: An analysis of 200 cases. Cancer. 1978;41:2250-66.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MFH classification: Differentiating undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma in the 21st Century. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1135-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soft tissue giant cell tumor of low malignant potential: A proposal for the reclassification of malignant giant cell tumor of soft parts. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:894-902.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant cell rich malignancies: A meta-analysis. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2018;8:225-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic tumors to the nail unit: Subungual metastases. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:280-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleomorphic soft tissue sarcoma metastatic to the skin of the scalp and groin. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:96-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma from a mediastinal sarcoma. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:310-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalp metastasis from malignant fibrous histiocytoma of bone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:S88-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malignant fibrous histiocytoma with in-transit metastasis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2011;3:164-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increased metastasis of malignant fibrous histiocytoma in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and non-hodgkin lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:738-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digital metastases of giant cell rich malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Sarcoma. 1999;3:167-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malignant fibrous histiocytoma masquerading as pyogenic granuloma. Orbit. 2017;36:122-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]