Translate this page into:

Cutaneous problems in elderly diabetics: A population-based comparative cross-sectional survey

Correspondence Address:

N Asokan

Prashanthi, KRA-11, Kanattukara PO, Thrissur - 680 011, Kerala

India

| How to cite this article: Asokan N, Binesh V G. Cutaneous problems in elderly diabetics: A population-based comparative cross-sectional survey. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:205-211 |

Abstract

Background: There are few population-based studies on prevalence of cutaneous problems in diabetes mellitus.Aims: To identify skin problems associated with diabetes mellitus among elderly persons in a village in Kerala.

Methods: In this population-based cross-sectional survey, we compared the prevalence of skin problems among 287 elderly diabetics (aged 65 years or more) with 275 randomly selected elderly persons without diabetes mellitus.

Results: Numbness, tingling and burning sensation of extremities,“prayer sign”, finger pebbling, skin tags, stiff joints and acanthosis nigricans were noted more frequently in diabetics as compared to non-diabetics. Ache in extremities, dermatophytosis, candidiasis, seborrheic keratoses/dermatosis papulosa nigra, xerosis/ichthyosis, idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, nonspecific itching, and eczema were equally frequent in both groups. Among the diagnostic categories, neurovascular, metabolic and autoimmune findings were associated with diabetes mellitus, whereas bacterial and fungal infections were not.

Limitations: Initial misclassification errors, no laboratory confirmation of dermatological diagnosis during survey, coexistence of findings related to aging and not analyzing the effects of glycemic level, concurrent diseases and medications.

Conclusions: Numbness, tingling and burning sensation of extremities, prayer sign, finger pebbling, skin tags, stiff joints and acanthosis nigricans were associated with diabetes mellitus among elderly persons in a village in Kerala.

Introduction

Skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus have been the subject of various hospital-based descriptive as well as comparative studies.[1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8] The type and frequency of reported manifestations have varied in different studies, probably due to inherent differences in the study population. The setting of research can also influence the findings. Hospital-based studies have an inherent selection bias, as patients with more severe forms of disease are likely to attend hospitals. Such studies may not accurately reflect the characteristics of disease in the general population.[9] This is particularly relevant for diabetes mellitus which is often asymptomatic. There are few population-based studies on prevalence of skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus.

Thalikulam Health Project is a community-led health intervention, details of which have been published earlier, being carried out in Thalikulam, a coastal village in the central part of Kerala.[10] Health interventions of the project are under the guidance of faculty members of Government Medical College, Thrissur. Health care of the elderly (aged 65 years or above) is one of the focus areas of the project in which faculty members from the departments of general medicine, psychiatry and dermatology are involved. Here, we report the findings of a population-based comparative cross-sectional survey on the skin findings among elderly persons with diabetes mellitus in Thalikulam.

Methods

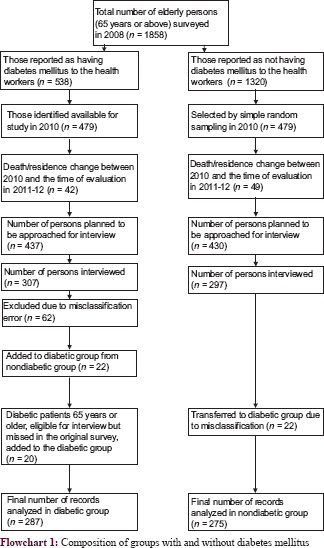

Thalikulam Health Project was initiated in the year 2008, by Thalikulam Vikas Trust, a non-governmental organization functioning in Thalikulam. Designated community health workers associated with the project conducted a preliminary survey on the general health problems in the community in 2008–2009. Of the population of 25,507, 20,942 people participated in this survey. In 2010, we reviewed this database and selected those who would have attained the age of 65 years by 2011 (when evaluation by dermatologists was planned to begin). We identified 1858 such persons who were given special identification numbers. Of them, 538 persons reported to the health workers that they had diabetes mellitus (they were either on treatment or had been advised to take treatment for diabetes mellitus). We verified the availability of such persons for health interventions in 2010, by excluding people who had died or changed residence between 2008 and 2010 which reduced the number to 479 persons. We selected an equal number of persons by a simple random method from the original list of 1320 persons who had reported to the health workers that they did not have diabetes mellitus. The final analysis included 287 persons with diabetes mellitus and 275 persons without diabetes mellitus (total = 562) after further modifications in the sampling frame as shown in [Flowchart 1].

Sample size calculated to compare for overall differences in skin manifestations between the two groups was based on expected prevalence of skin findings as 88.3% among persons with diabetes mellitus and 36% among persons without diabetes mellitus.[5] Using Fleiss method with continuity correction and assuming a power of 80% and expecting two-sided significance of alpha as 0.05% and an equal number of cases and controls, this came out as 17 in each group.[11] However, we decided to enlist all the elderly persons having diabetes mellitus and an equal number of persons without diabetes mellitus to increase the power to detect differences in the prevalence of individual cutaneous findings. For example, the sample size required to compare prevalence of acrochordons in the two groups would be 115 in each group, for an expected prevalence of 24.6% in the group with diabetes mellitus and 9.8% in the group without diabetes mellitus.[5]

All persons in the self-reported group without diabetes mellitus were tested for fasting blood sugar to pick up those who actually had diabetes mellitus but were unaware of it. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood sugar ≥126 mg% on two occasions two weeks apart. Such persons were transferred from the group without diabetes mellitus to the group with diabetes mellitus. Study interviews were carried out between May 2011 and February 2012 in special camps arranged close to their houses. Thalikulam Vikas Trust provided logistical support for the camps. All participants were evaluated by one of the authors for the presence of skin findings with emphasis on previously known and reported findings in diabetes mellitus. The findings were recorded in a proforma. Skin findings were further classified into various etiopathogenetic categories such as neurovascular manifestations, bacterial infections, fungal infections, metabolic manifestations, autoimmune conditions and other miscellaneous findings. Results in the two groups were compared. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Government Medical College, Thrissur.

Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage and quantitative variables as mean with standard deviation. Pearson's Chi-square test with continuity correction was used to compare the differences in prevalence of each variable in the two groups. For etiopathogenetic categories, two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

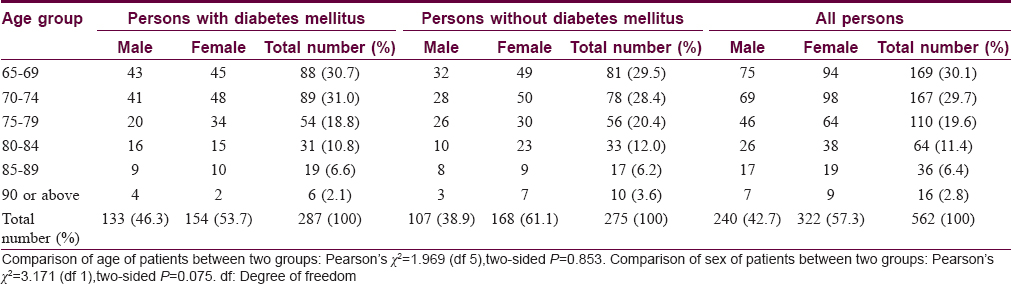

Demographic characteristics of the subjects are shown in [Table - 1]. Age ranged from 65 to 105 years in the diabetes group and from 65 to 99 years in the nondiabetes group. Mean age of persons with diabetes mellitus was 73.45 (±6.72) years and that of persons without diabetes mellitus was 73.87 (±6.87) years (P = 0.853). Both groups had a greater proportion of women (168 [61.2%] in the group without diabetes mellitus compared to 154 [53.7%] in the group with diabetes mellitus) (P = 0.075). Mean duration of diabetes mellitus was 9.72 ± 7.78 years (range: 2 months–40 years). Duration was <5 years in 86 (30%) patients, between 5 and 9 years in 67 (23.3%) patients, between 10 and 14 years in 61 (21.3%) patients and 15 years or more in 73 (25.4%) patients.

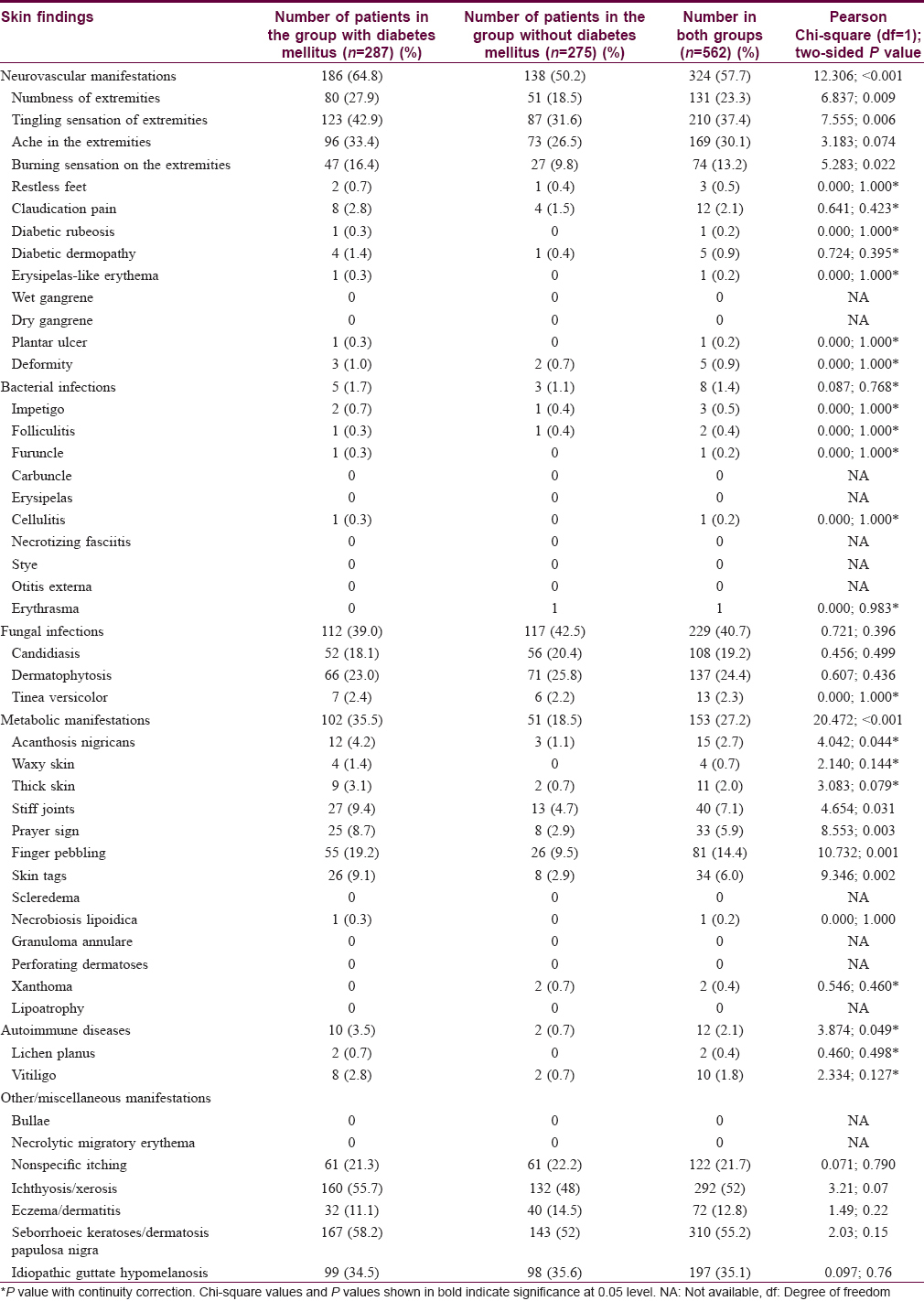

Common dermatological findings reported by 287 patients with diabetes mellitus were neurovascular symptoms such as tingling (n = 123; 42.9%), aches (n = 96; 33.4%), numbness (n = 80; 27.9%) and burning sensation (n = 47; 16.4%) of extremities; superficial mycoses such as dermatophytosis (more commonly onychomycosis and intertriginous tinea pedis; n = 66; 23%) and candidiasis (mostly chronic paronychia of fingers and toes; n = 52; 18.1%); metabolic manifestations such as finger pebbling (n = 55; 19.2%), stiff joints (n = 27; 9.4%), skin tags (n = 26; 9.1%) and “prayer sign” (inability to closely approximate the palmar surfaces of fingers as in a prayer position; n = 25; 8.7%) and miscellaneous features such as seborrheic keratoses/dermatosis papulosa nigra (n = 167; 58.2%); xerosis/ichthyosis (n = 160; 55.7); idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (n = 99; 34.5%); non-specific itching (n = 61; 21.3%) and eczema (n = 32; 11.1%) [Table - 2]. Among these, numbness (P = 0.009), tingling (P = 0.006) and burning sensation (P = 0.022) of extremities, prayer sign (P = 0.003), stiff joints (P = 0.031), acanthosis nigricans (P = 0.044), finger pebbling (P = 0.001) and skin tags (P = 0.002) showed an association with diabetes mellitus. Manifestations such as restless feet, claudication, rubeosis, dermopathy, erysipelas-like erythema, plantar ulcers, deformities, impetigo, folliculitis, furuncle, cellulitis, erythrasma, lichen planus and xanthoma were uncommon. Features such as wet/dry gangrene, carbuncle, erysipelas, necrotizing fasciitis, stye, otitis externa, erythrasma, bullae, necrolytic migratory erythema, scleredema, granuloma annulare, perforating dermatoses and lipoatrophy were not seen in any patient.

Among various etiopathogenetic categories, neurovascular (P < 0.001), metabolic (P < 0.001) and autoimmune manifestations (P = 0.049) were associated with diabetes mellitus, whereas bacterial (P = 0.768) and fungal infections (P = 0.396) were not.

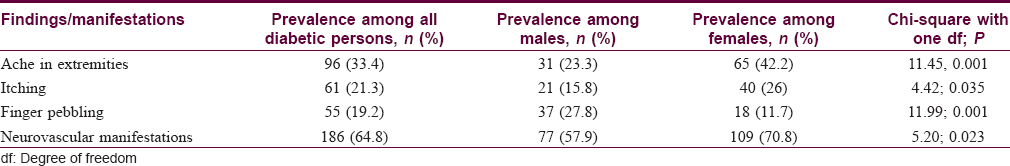

We analyzed how age, sex and duration of diabetes mellitus affected the findings. The prevalence of candidiasis, dermatophytosis, acanthosis nigricans and pebbly fingers showed a declining trend with advancing age of the patients [Table - 3]. Among the etiopathogenetic categories, the prevalence of fungal infections and metabolic manifestations declined with advancing age. Ache in extremities and non-specific itching was more common among women, whereas finger pebbling was more common among men [Table - 4]. Neurovascular manifestations were more common among women compared to men. The prevalence of acanthosis nigricans and neurovascular manifestations (as a group) increased with greater duration of diabetes mellitus [Table - 5]. No other individual findings or category of findings showed any consistent association with age, gender or duration of diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

Results of this population-based comparative cross-sectional survey among persons aged 65 years or more in Thalikulam, a coastal village in central part of Kerala indicate that neurovascular symptoms (numbness, tingling and burning sensation of the extremities) and metabolic manifestations (acanthosis nigricans, stiff joints, prayer sign, pebbly fingers and skin tags) were significantly associated with diabetes mellitus. Though lichen planus and vitiligo were individually not associated with diabetes mellitus, autoimmune diseases, when collectively considered, had a moderate association.

Similar to most of the previous studies, fungal infections were found to be common among persons with diabetes mellitus.[3],[5],[7],[12] However, in our study, we found that such infections (mostly onychomycosis, intertriginous tinea pedis and candidal paronychia) were equally common in persons without diabetes mellitus. Several factors might have contributed to a high prevalence of fungal infections irrespective of diabetic status in our study: (a) advanced age – a known predisposing factor for onychomycosis and (b) coastal location and rural background of the population entailing more frequent contact with water and wet soil predisposing to candidal paronychia and intertriginous tinea pedis.[13] Our findings suggest that if such predisposing factors are present, diabetic status may not be an additional risk factor for cutaneous fungal infections. The decreasing trend of fungal infections with advancing age seen among this elderly population may be explained by the expectedly decreased activities entailing contact with water in very old persons. Bacterial infections were rarely encountered in our study, unlike several previous hospital-based studies from India.[3],[5],[7]

Our study showed a high prevalence of neurovascular manifestations among persons with diabetes mellitus compared to previous reports from India.[7],[14],[15] A comparable high prevalence was reported in hospital-based studies from Peru (56.6%) and the USA (43%).[16],[17] One population-based study from Chennai reported a prevalence of 24.6% for neurological and 23.6% for cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus, whereas another study, also from Chennai, reported a 25.7% prevalence of neuropathy.[15],[18] In our study, neurological manifestations were more common among those with greater duration of diabetes mellitus, as expected. However, the increased frequency of neurological symptoms among women noticed in our study warrants further exploration.

The prevalence of acanthosis nigricans was found to be low in this community when compared to various hospital-based studies. Prevalence of skin tags was higher than that reported by Nigam and Pande, and Mahajan et al., but considerably less than that reported by Timshina et al.[3],[5],[7] Xanthomas were not seen in any of our elderly persons with diabetes mellitus, whereas two (0.7%) persons without diabetes mellitus had xanthelasma. Finger pebbling was common (seen in nearly one-fifth) in this population, more frequent than reported by Timshina et al.[5] Although finger pebbling was seen among persons without diabetes mellitus too, its prevalence was significantly associated with diabetic status in our study. Findings such as acanthosis nigricans, skin tags and pebbly fingers are easily identifiable by medical practitioners, health workers as well as by general public. Increased awareness about such findings could help to detect diabetes mellitus earlier in the community.

Yosipovitch et al. highlighted sclerodermoid changes of hands as strongly associated with limited joint mobility in type 1 diabetes mellitus.[6] Our study did not have a diagnostic category as 'sclerodermoid'. However, stiff joints and prayer sign, which are indicative of sclerosis of fingers were found to be strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.[19] Limited joint mobility is reported in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, more commonly in the former.[20] Sclerodermoid changes are believed to result from increased glycosylation of fibrous tissue.[21],[22]

Vitiligo and lichen planus were not associated with diabetes mellitus in our study. In the study by Timshina et al. which included patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, vitiligo was associated with diabetes, whereas lichen planus was not.[5] Autoimmune diseases have been associated more with type 1 diabetes mellitus.[23]

Manifestations such as non-specific itching, eczema, xerosis/ichthyosis, seborrheic keratoses and idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis were common among diabetic persons but their prevalence was not significantly different from non-diabetic persons. These features probably represent changes related to aging skin rather than changes in diabetes mellitus.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, initial assignment of persons into groups with or without diabetes mellitus was based on history obtained by the health workers. This was often inaccurate, as reflected in a large degree of misclassification, especially among the self-reported non-diabetic group. However, we reclassified them correctly based on fasting blood sugar before the final analysis. Secondly, the medical camps in which the participants were evaluated had no facilities for investigations. However, most conditions identified were common which enabled a straightforward diagnosis by dermatologists. Wherever needed, confirmation was obtained by referral to the tertiary care center. Thirdly, the response rate to the survey was only about 70 per cent. Access to health care facilities is often restricted for the elderly with various ailments, who find it difficult to go out of the house without help. We tried to overcome this constraint to some extent, by conducting camps close to their homes and by visiting the houses of bedridden persons. Fourthly, as we had not estimated glycemic levels of diabetic patients, we could not analyze any possible influence it could have on the findings. We also could not analyze the effect of any coexisting diseases and medications on the findings as we could not obtain reliable data about these. Fifthly, as the study was confined to a single village, it may not be correct to extrapolate its findings to other populations with different ethnic, geographic and cultural characteristics. Finally, the findings of a study restricted to elderly persons may not be directly comparable to other studies conducted on patients with diabetes mellitus of all age groups. It is possible that some of the conditions observed in this population may be a reflection more of advanced age, rather than diabetes mellitus. However, the comparative design of our study improved the validity of our findings.

Major strengths of our study are a large sample size compared to most previous studies, the comparative design and community setting which have seldom been used in previous studies; coverage of all accessible elderly persons with diabetes mellitus in the community (which minimized sampling error) and an expectedly higher accuracy of diagnosis made by qualified dermatologists. Cutaneous findings such as stiff joints, pebbly fingers, skin tags and prayer sign can be easily picked up during clinical evaluation. If primary care physicians and health workers are trained to identify such findings, it could facilitate early detection of diabetes mellitus.

The diabetic cohort in Thalikulam offers promising prospects for further studies. It would be interesting to relate the skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus with various systemic complications and ultimately to the overall morbidity and mortality of these patients. It would be useful if one can identify skin markers capable of predicting important systemic complications of diabetes mellitus. Correlating the commonly associated dermatological findings in diabetes mellitus with glycemic levels is a good prospect for further studies.

Conclusions

Numbness, tingling and burning sensation of extremities, prayer sign, finger pebbling, skin tags, stiff joints and acanthosis nigricans were associated with diabetes mellitus among elderly persons in a village in Kerala. Several well-known associations of diabetes mellitus reported in earlier hospital-based studies such as diabetic rubeosis, dermopathy, necrobiosis lipoidica, granuloma annulare, scleredema, xanthoma and perforating dermatoses have limited value as markers of diabetes mellitus in a population setting due to their rarity. In this study, infections, though frequent among persons with diabetes mellitus, were equally frequent in non-diabetics.

Acknowledgment

- Thalikulam Vikas Trust for organizing the camps and for preliminary data entry

- Dr. Biju George, Associate Professor of Community Medicine, Government Medical College, Kozhikode, for helping with statistical analysis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Thalikulam Vikas Trust organized the camps and helped in preliminary data entry.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Romano G, Moretti G, Di Benedetto A, Giofrè C, Di Cesare E, Russo G, et al. Skin lesions in diabetes mellitus: prevalence and clinical correlations. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1998;39:101-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Fajre WX, Pérez L, Pardo J, Dreyse J, Herane MI. Cross sectional search for skin lesions in 118 diabetic patients. Rev Med Chil 2009;137:894-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Nigam PK, Pande S. Pattern of dermatoses in diabetics. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2003;69:83-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Wahid Z, Kanjee A. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. J Pak Med Assoc 1998;48:304-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Timshina DK, Thappa DM, Agrawal A. A clinical study of dermatoses in diabetes to establish its markers. Indian J Dermatol 2012;57:20-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Yosipovitch G, Hodak E, Vardi P, Shraga I, Karp M, Sprecher E, et al. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in IDDM patients and their association with diabetes risk factors and microvascular complications. Diabetes Care 1998;21:506-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Mahajan S, Koranne RV, Sharma SK. Cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2003;69:105-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Pavlovic MD, Milenkovic T, Dinic M, Misovic M, Dakovic D, Todorovic S, et al. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in young patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1964-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:511-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Asokan N, Praveenlal K, Shaji KS. Evidence informed community healthcare in developing countries: Is there a role for tertiary care specialists? Natl J Community Med 2011;2:496-7. Available from: http://www.njcmindia.org/home/article/3/2/2011/Oct-Dec/35. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 12].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Sample Size Calculation for Unmatched Case Control Studies. OpenEpi Version 3.03.17. Available from: http://www.web1.sph.emory.edu/cdckms/sample%20size%202%20grps%20 case%20control.html. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 12].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Eckhard M, Lengler A, Liersch J, Bretzel RG, Mayser P. Fungal foot infections in patients with diabetes mellitus – Results of two independent investigations. Mycoses 2007;50 Suppl 2:14-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: Results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol 1992;126 Suppl 39:23-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Rao GS, Pai GS. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1997;63:232-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Pradeepa R, Anjana RM, Unnikrishnan R, Ganesan A, Mohan V, Rema M. Risk factors for microvascular complications of diabetes among South Indian subjects with type 2 diabetes – The Chennai urban rural epidemiology study (CURES) eye study-5. Diabetes Technol Ther 2010;12:755-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Lazo Mde L, Bernabé-Ortiz A, Pinto ME, Ticse R, Malaga G, Sacksteder K, et al. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy in ambulatory patients with type 2 diabetes in a general hospital in a middle income country: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2014;9:e95403.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Wang W, Balamurugan A, Biddle J, Rollins KM. Diabetic neuropathy status and the concerns in underserved rural communities: Challenges and opportunities for diabetes educators. Diabetes Educ 2011;37:536-48.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Mohan V, Shah S, Saboo B. Current glycemic status and diabetes related complications among type 2 diabetes patients in India: Data from the A1chieve study. J Assoc Physicians India 2013;61 (Suppl 1): 12-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Upreti V, Vasdev V, Dhull P, Patnaik SK. Prayer sign in diabetes mellitus. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2013;17:769-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Rosenbloom AL. Limitation of finger joint mobility in diabetes mellitus. J Diabet Complications 1989;3:77-87.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Monnier VM, Vishwanath V, Frank KE, Elmets CA, Dauchot P, Kohn RR. Relation between complications of type I diabetes mellitus and collagen-linked fluorescence. N Engl J Med 1986;314:403-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Lyons TJ, Kennedy L. Non-enzymatic glycosylation of skin collagen in patients with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and limited joint mobility. Diabetologia 1985;28:2-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2010;33 (Suppl 1):S62-9. Erratum in: Diabetes Care 2010;33:e57.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,158

PDF downloads

2,418